Xinta's music lessons - Lesson 7

The previous lesson was more “dense” than I've planned at the beginning, so this one will be shorter and likely less demanding.

I've talked about triads (chords made of three sound: a root, the 3rd and the 5th) and have given particular importance to the triads on I, IV and V because of their role in important cadences, that is, formulae used to give the feeling of a closing musical phrase, almost like certain punctuations in writing — which impose a specific inflection of the voice, as for instance in “It's raining.”, “It's raining!” or “It's raining?”. (In English grammatically correct questions have Verb-Subject instead of Subject-Verb, but nonetheless interrogative inflections are recognized properly also if the order S-V is kept.)

The triads made of a minor or major and a perfect fifth are considered consonant, because made of intervals which are considered consonant: perfect fifth and minor or major thirds. These are indeed considered by some theorists imperfect consonances, but these classifications are partly historical/traditional, partly cultural; shortly: they aren't objective (e.g. imperfect consonances were considered dissonances in the past).

Unison and octave are surely consonant — this isn't disputed. Also, perfect fifth is consonant, and if you play it, you very unlikely will disagree. Perfect fourth is consonant, too, almost like fifth, but anyway less than unison and octave. All the other intervals could be classified according to a “scale of increasing dissonance”, starting from major and minor thirds, which are considered still consonant, but “imperfectly”, not like unison, octave, perfect fourth and fifth.

Some intervals were considered so dissonant that they were carefully avoided for a lot of time; diminished and augmented intervals began to be used in “modern” music, but they were avoided or unknown in the ancient time: we could say that ancient music was someway more tied to “strict” consonance than today.

A notable example of dissonant interval with a long history is the so called tritone (6 semitones, namely three tones, hence tri-tone; i.e. it is an augmented fourth or a diminished fifth and occurs for instance on any major scale between IV and VII, and on natural minor scales between II and VI), which won the label diabolus in musica (devil in music), and old harmony manuals forbidden its usage. This sort of curse was definitively broken in modern classical music (and in popular music never existed, I think), even though the tritone appeared already before, and it is still considered a dissonance novices must handle carefully. I believe the reason is that, being an interval of the scale even without altered notes, it can be “hidden” (i.e. present not intentionally), not because it is a dangerous dissonance for itself.

Of course the tritone was and is used in a lot of music we've learnt to recognize; e.g. in a masterpieces like this:

(html comment removed: dead imgsafe: i.imgsafe.org/f2e79cd39b.png )

It appears as a diminished fifth between the C♯3 played by the cellos (Vc for ViolonCelli, I've used Italian abbreviations) and the G4 by the second violins and then the G5 played by the first violins. The C♯ resolves ascending to the D (then this ascends to E♭). Anyway in this case the tritone can be easily spotted because the ♯ on the C is a signal that augmented or diminished intervals could appear (you still need to take a look to the harmony).

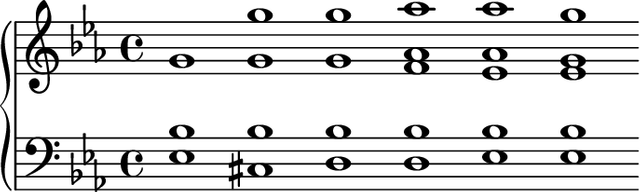

If you cut off all the things beyond harmonic matters, the piece exhibits this harmony:

(html comment removed: dead imgsafe: i.imgsafe.org/f3c27ae622.png )

Let's try to show something about this piece. Maybe I'm looking a little bit into the future of this and other lessons.

- The B♭ is always present: first played by the violas and then by the second violins, in alternation with another note. The B♭ is the V of the tonality (E♭ major); a prolonged note which is kept, producing consonance and dissonance as other voices change notes, is called a pedal note. The pedal notes are usually I or V, as in this case. Pedal notes are the lowest note; when they aren't the lowest, they are called inverted pedal note. In the previous lesson we've seen that you “feel” a chord even when the notes aren't played simultaneously but sequencially. The second violins keep the pedal note playing it in alternation with G, F and then E♭. (The violas don't play it continuously, anyway, because the “slash” you see on the dotted minims is a tremolo)

- The chords are mostly “airy”: the notes are distant, therefore you could almost always add a note of the chords between any pair of adjacent notes, for instance between C3-B♭3 you can add a G3: between other pairs there's even more room; there are three exceptions in the last three chords: the pairs F4-A♭4, E♭4-A♭4, and E♭4-G4 don't allow for an “insertion”. When you can do it, the chord is said to be in a open position (also: wide disposition), otherwise it is in a close position (also: narrow disposition). In order to have a wide disposition, notes must be more than a fourth apart. Open position is often used in the bass voices, where “narrow chords” would sound gloomy and “harsh” (but, of course, if it is what you want, then…). If there are both situation, do we have a close or open position?

- The diminished fifth (the tritone) happens between notes which are “far”; in fact we have indeed a diminished 12th and a diminished 19th, but if we reduce them to the simple interval, then it's a diminished 5th. However the actual distance is important: dissonances tend to become weaker when they happen between “far” sounds. When the C♯3 is played by the cello, second violins are already playing G4 (not G3); however the diminished fifth C♯-G someway is stressed because of the off-beat debut of the G5 played by the first violins. Try to play C♯3-G3, C♯3-G4, C♯3-G5.

- The C♯3 plays together with the pedal note B♭3; C-B is a major 7th, C-B♭ is the minor 7th and so C♯-B♭ must be a diminished 7th. The tritone isn't the only dissonance, but it occurs between the lowest and the highest parts, and this is an important fact. It is like if those parts were actors in front of the stage, so that what they do catches the eyes more than what the other background actors do.

- The tension built with the dissonance of the diminished fifth (and diminished seventh) is released (for now) when the C♯ ascends to D. Which chord do we have here? There are D3, B♭3 and G4+G5; these notes are those of the G minor triad (G, B♭, D), but the root note, namely G, isn't the lowest one as we've seen so far; instead, it is the highest note, and in the bass part we've D, the fifth of the chord instead of the first. This is an inversion, and exactly it's the second inversion, because the fifth is the lowest note. The chord isn't made by a third and a fifth anymore. More on this in the current lesson. G minor is the III of the E♭ major key.

- The last but two chord is a B♭ major with the minor seventh, also called a dominant seventh chord; the last chord shown is clearly a E♭ major. What about the last but one? It seems a ninth chord (a pentad, namely a 5-note chord) but without the 3rd and the 7th: A♭ (C) E♭ (G) B♭, so it would be a minor ninth chord on A♭ (IV of E♭) . Notes of a chord can be omitted (we'll see this), but indeed in classical harmony handbooks the 3rd is considered mandatory (because it establishes if the chord is minor or major) — either it isn't a strict rule for classical masters (or modern composers), or this analysis is wrong — it could be, of course (by the way, it isn't a Schenkerian analysis); there's this classification: suspended chords, which are chords with the 3rd replaced by 2nd (which is, in a different octave, a ninth) or perfect fourth. It seems we can stick to the idea of the IV (A♭), after all. Another interesting thing: B♭3-E♭4, E♭4-A♭4 and also E♭3-A♭5 (the lowest and higher notes) are perfect fourths (in the latter case you must transpose the notes in the same octave). Maybe it can be read as a quartal chord (with E♭ and A♭ doubled). You could also say that it is a E♭ (major?) without the 3rd but with the 11th… The context suggests this is less likely.

- How a dissonance is introduced (prepared), how long it lasts, and how it is resolved is relevent. The C♯ is reached through a descending conjuct melodic motion, while a consonant chord (precisely the I) is playing, then this dissonance resolves ascending, almost like a leading tone ascending to its tonic… but indeed landing on the true leading tone of the key, and hence to the actual tonic.

- Passing notes connect by step two different notes which are part of the harmony. Passing notes produce dissonance: they aren't part of the chord, namely they aren't part of the playing harmony (of course they add nuances to it). Here we have E♭3 D3 (passing note) C♯3: D is the passing note which connects E♭3 and C♯3 (so that the melody moves by steps in this passage). This passing note (D) temporarily forms the chord G minor (G B♭ D), second inversion. Should this “temporary chord” gain a mention? The answer is the conseguence of the answer to another question: does the listener “feel” that chord? Maybe the listener perceives only a passing note. Things could be different if the tempo would be slower. If you remove the passing note, you change the melody, but the harmony isn't hurt. There are other kind of off-the-harmony notes and they get their names according to how they relate with the in-harmony notes, if they step or jump, if they land on the same previous note or note, and so on.

I've tried this analysis to give you an idea of how many things there are in a score and to show a real example of things we're going to see in this lesson or in future lessons. Just another point, this one about the rhythm:

- notably the highest G starts “displaced” with respect to the rhythmic pattern, so that the notes are off-beat; this is syncopation.

Positions of a chord (and voicing)

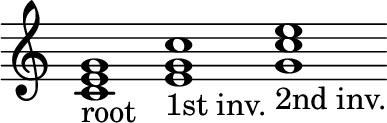

Let us consider triads first; the same concepts apply to chords with more than three notes. Let us consider our usual C major; the three notes of a C major are C, E, G, and we've stacked them starting from C (the I) up. We can move notes up and down by an octave, though, so that the lowest note isn't C (the root) anymore.

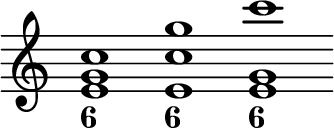

Changing the lowest note changes the position of the chord. We obtain the so called inverted chords; the position with the root note at the bass is called root position, then we have first inversion and second inversion.

(html comment removed: dead imgsafe: i.imgsafe.org/38f6d66c7c.png )

The first inversion is obtained by moving the I by one octave up. The second inversion is obtained by moving the I and the III one octave up (starting with the root position).

But altogether with the bass, we've changed also the highest note. Indeed for each inversion we could adjust the notes so that the highest note is one of the other two, keeping the same bass, hence keeping the position.

By doubling the bass note, we can have three possibilities (one per note) for each position.

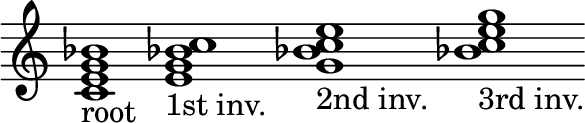

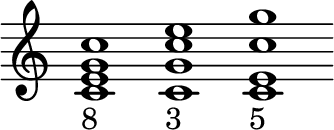

Chords made of more than three (different) notes have three inverted positions. Let's see a dominant seventh chord on C as an example.

In this case too we can keep the same bass and move the other notes so that the highest note is one or another. In general we can move all notes up and down by octaves: provided that we keep the same bass, we obtain the same inversion (or the root position if the root note is the lowest), but a different melodic position.

This “arrangement” of notes is sometimes called voicing. Doing so we also can change between narrow and wide disposition.

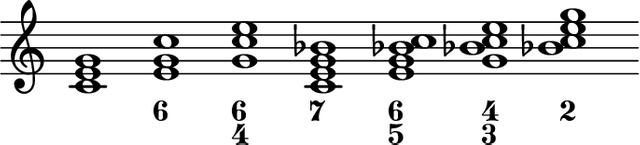

Notation, figured bass

In case we need to mark these “variants” of a chord we can use numbers put below the bass note. These numbers specify the intervals with respect to the bass note, and expressed always as steps or degrees. The root position could be marked with 3 and 5, because is made of a third and a fifth. But this is usually implied.

In the first inversion, the intervals are 3 and 6 (it's made of a third and a sixth); usually the 3 is omitted and only the 6 is left, and the first inversion could also be called a chord of sixth.

In the second inversion, the intervals are 4 and 6 (it's made of a fourth and a sixth), and in this case both are specified.

Using the same idea, a 4-note chord can be marked with just a distinctive 7. The first inversion has 3, 5 and 6, but the 3 is omitted and so it is marked only with 5 and 6. The second inversion of a chord of seventh is marked as 3 and 4 (in this case we omit the 6, which isn't distinctive); the third inversion can be marked just through the first interval, namely 2. We can keep the intervals which alone can identify the inversions, and leave out the rest.

These annotations hold also when we move the notes up and down by octaves (different voicings), provided that we keep the same bass (otherwise we're changing the inversion). E.g.

This notation can be used in general and is called figured bass. We can also specify if the intervals are altered, adding flat, natural or sharp near the numbers, or specifying if it's diminished or augmented. Given a bass, the notation makes it possible to specify the intended harmony.

Here we have, in order and with a possibile notation for the chord:

- C major, root position (not specified from here on) (C: C major)

- G major, second inversion (G/D: G major with D as bass)

- E major: the ♯ alone could be written also as ♯3, which means that the third is “sharped” (E; the key has E minor)

- F (minor) half diminished seventh (Fø or Fm7♭5)

- G (major) dominant seventh (G7)

- A (minor) diminished (A°)

- G (major) dominant seventh, first inversion (G7/B)

- G (major) dominant seventh, second inversion (G7/D)

- C major (C)

Also the melodic position can be annotated. Like this:

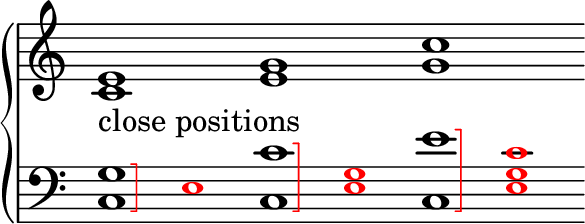

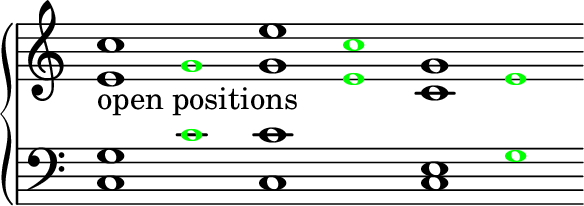

Open and close positions

In the close position of a chord we can't move another sound of the chord in between two notes. It happens when two notes are distant a third or a fourth (or a second). When this applies to all adjacent notes, we have a close position (narrow disposition). Indeed the bass (the lowest note) isn't considered, so that the following chords are in close position even if the bass part is distant more than a fourth from its nearest part (and it's possible to put other notes in between, notated as red notes).

In the previous example the root note is at the bass (we have the root position of the chord) and always doubled in some other part (this is the chosen voicing with four voices and triads).

In the open position, instead, the distance between all adjacent parts must be more than a fourth (it hasn't to be so between the lowest and the one immediately above). If we are using only triads, these intervals, after “reduction”, will be fifths and sixths.

This is according to the definition; in a composition, you can change between open and close positions, and viceversa, according to your needs, and your needs depend on the “effect” you want, but can be also limited by the rules of harmony and how the voices need to move; at least until you care and want to comply — your ears (and your audience's ears) can be, however, the final judge, no matter what the rules say.

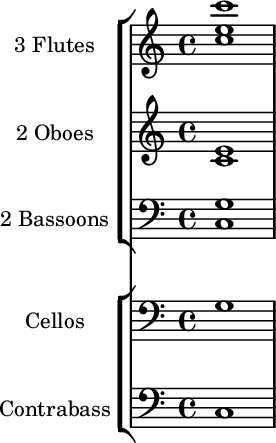

In a complex score, however, you may have several instruments, each with its register; that is, each instrument covers a range of notes; registers can overlap partly, of course; however we could have a situation like in the following small orchestra score playing a C major. Is it in a open or close position?

Reading the score above consider that the contrabass (also called double bass) is notated one octave higher; that is, the real notes play one octave lower.

Because of this, the lowest note is the C2 played by the contrabass, not the C3 played by the bassoon. So the bassoons' notes C3-G3 relationship must be considered; and it's open. But G3 (played by bassoon), C4 and E4 (played by oboes) are, considered by themselves, close. And so it is for the C5-E5 (played by 2 flutes), but it isn't so between E4 (oboe) and C5 (flute), nor between E5 and C6 (flutes), which would suggest us the position is open.

So, is it a close or open position?

Even if we consider the pair C2-C3 as bass, we have G3-C4-E4 and C5-E5 which say close, but E4-C5 and E5-C6 which say open. Who wins? Does it sound “airy” or “filled”? I think it's hard to tell objectively.

If you “decompose” the parts in registers, maybe you can say it's a close position after all, but with doublings. The only “exception” would be E5-C6 played by two flutes, but C6 could be considered a doubling as well, just to keep the melodic position (8) with the bass.

Because polyinstrumental music exhibits often this situation (the features of the instruments may dictate partly the voicing), we can say that open positions appear more often than close ones.

Inversions and intervals

I've already described chords as “superposition of intervals” (at least implicitly): the triad is made of a third and a fifth, with respect to the root note, which was also the lowest note in our initial examples (I showed chords in their root position). A seventh chord has also the seventh (hence its name). A major triad is made of a major third and a perfect fifth; but we can also say that it is made of a major third and a minor third, because the interval between the third and the fifth is a minor third. So we can say that a perfect fifth can be decomposed into the sum of a minor third and a major third.

This is true for root position, but when we invert a chords, we also change the relationships between the notes. So we hear not just thirds and fifths (and sevenths), but also (depending on the inversions) fourths and sixths (and seconds).

The chord is the same, but it's “character” is different because different is the character of the intervals fourth and sixth (and second). Also the “dissonant character” of a dissonant chord like a seventh chord changes: the “collision” of a seventh is different from the one of a second.

However we can produce those intervals also keeping the root position, because by definition we can move the higher parts as we prefer and need, and when “voicing” we likely will double notes and mix open and close positions in different registers, so that we obtain a complex and peculiar “texture” which hasn't to be the same for each register.

Just a word before the next lesson

Even if it could seem not so to you, this lesson is rather light. By trying an analysis on a small great piece of music I've pushed things a little bit far, but the idea was to drop concepts in advance, just to start to make you comfortable with them, let them sink and then repeat and expand them in future.

The “core harmony” of this lesson is just this:

- Reprise of consonance and dissonance, with few details on consonant and dissonant intervals; tritone.

- Inversions and figured bass; open and close positions; melodic positions; voicing.

Grazed topics:

- Figured bass and voicing.

- Harmonic analysis; chords with more than 3 notes.

- Tension-release “pulse”; preparation-resolution.

- Non-in-harmony notes/tones (non-chord notes/tones, non-harmonic notes/tones, embellishing notes/tones).

- Pedals.

- Syncopation.

The site imgsafe which I used to use to host images can't be reached anymore, I don't know if it is a temporary or permanent failure; I've moved to imgur for this lesson, I need also to check if the previous lessons can still show images.

I've a youtube channel now, I likely will test it after posting this lesson; then I'll use it to make you listen to musical passages.

If you spot errors, or you have suggestions, please drop a comment! Thank you!

Index of the lessons so far (the current one included)

- Lesson 1: basic knowledge about sound.

- Lesson 2: dissonance, consonance, tuning, 12-tones equal temperament, notes' names and notes on a staff, treble and bass clefs.

- Lesson 3: semitones, duration, beaming, tempo.

- Lesson 4: time signature, downbeat, upbeat, rests, ascending major and natural minor diatonic scales, key signature, circle of fifths.

- Lesson 5: scale degrees, more scales, intervals.

- Lesson 6: intervals, harmony, triads, tonality, diatonic modes, Gregorian modes.

- Lesson 7: harmony, consonance, dissonance, analysis, inversions, voicing, figured bass

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.