Xinta's music lessons - Lesson 3

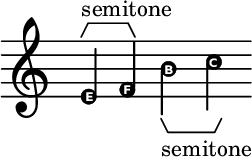

Having read the previous lesson you know that an octave, i.e. the interval between a note with pitch f and another one with pitch 2f, is divided into 12 “tones” (in 12-tones equal temperament). Here the “tone” is used as a generic word (a tone is just a sound with a specific pitch), but the terminology in use calls the interval between one of these “tones” and the next one a semitone — I've already used this term when explaining what the sharp (♯) and the flat (♭) signs are: the former raises the pitch of a semitone, the latter lower the pitch of a semitone.

A semitone is called also half tone (semi- is a Latin prefix which means exactly that: “half”), or half step. Two semitones make a tone (exactly how ½+½ makes 1). The semitone is the smallest interval in our western typical music, but it isn't the smallest interval in other musical cultures, or music which is considered experimental and sounds strange to our ears trained and used to what I've called our western typical music. Smaller intervals are possible, and in this case we talk of microtonal music; notably arabic music uses quarter of tones (the octave is divided into 24 tones instead of 12).

If the intervals between the “natural” notes (white keys on a keyboard instrument like a piano) were whole tones, we would have six of such notes. Instead we have seven “natural” notes. This means that there are two pairs of notes whose interval between each other is a semitone. If you was focused on the previous lesson, you should have noticed that they exist C#, D#, F#, G#, A#, but not E# and B#.

The interval between E and F, and between B and (upper) C, is a semitone. So E# is nothing but F, Fb is nothing but E, B# is nothing but C, and Cb is nothing but B. I've already said that C# = Db, D# = Eb and so on. All these notes which have the same pitch (in our equal temperament) — they belong to the same pitch class — but different “nomenclature”, are enharmonic.

Duration (and beaming)

Take a better look at the “shape” of the notes: the position of the “circle” (the notehead or simply head) determines the pitch, i.e. if the note is a C, a D, a E… and so on. Thus, why is it a filled head, and what is that line attached?

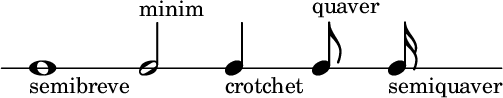

The notes on the staff must say the pitch, but also how long the note will play. All the notes I've written so far were quarter notes, or crotchet. It means that their durations are 1/4. But this is a fraction… One fourth of what? Of a whole note, also called semibreve (which means “half breve”, where the breve has double the duration of a semibreve… and in fact it is also called double whole note).

The whole note is a note which lasts four times a single quarter note… It sounds a little bit of circular? It is, and this should make you think that notes' durations are relative to an arbitrary unit: I say that a quarter note lasts one fourth of a whole note; there are notes which last half of a whole note, or half of a quarter note, that is, they last one eighth of a whole note. And so on, I can multiply by 2 or divide by 2 the duration of any notes.

Indeed the double whole note is rarely used, especially in pop music; quadruple whole note, or longa, and octuple whole note, or maxima, existed, but they are not used anymore in contemporary music; and 16 times the duration of a whole note… it hasn't ever existed a notation for this… This is way I will consider the whole note as the longer note available.

So the whole note is the unit of time and all the other durations are fractions of the form 1/2n: 1/2 (half note or minim), 1/4 (quarter note or crotchet — by the way, it's semiminim[a] in Italian, meaning half of a minim[a]), 1/8 (eighth note or quaver), 1/16 (sixteenth note or semiquaver — remember, semi- means “half of”), 1/32 (thirty-second note or demisemiquaver — demi- is another prefix from Latin, with the same meaning of half), 1/64 (sixty-fourth note or hemidemisemiquaver — hemi- is another prefix, this time from Greek, meaning again “half”), 1/128 (hundred twenty-eighth note or semihemidemisemiquaver), 1/256 (two hundred fifty-sixth note or demisemihemidemisemiquaver — see how the prefix “half” is repeated…).

It isn't complicated and the notation is easy:

The last note I've written is a semiquaver (1/16 note). How do you write a demisemiquaver, i.e. a 1/32 note? You simply add another flag to the stem (vertical line attached to the notehead). Each flag added, divides the duration by two. This is an easy to remember notation; you only have to remember that semibreve is 1, minim is 1/2, and semiminim is 1/4 (if you use the American names, it comes even easier). From a quarter note on, you just add flags to halve the duration of the note with one flag less: the semiquaver (1/16) has two flags, so its duration is half the duration of the note with one flag, that is a quaver (1/8) or a eighth note.

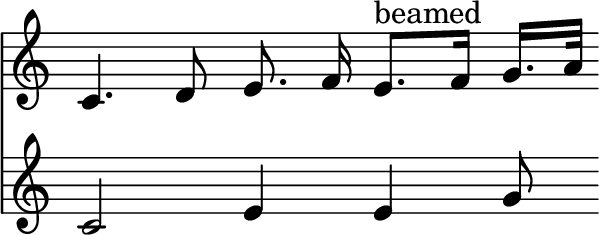

When notes with flags come one after another, they can be “joined”: the flags become “lines” extended from one stem to another. These “lines” are called beams, and we can say that the notes are beamed. Beamed notes are grouped notes, and this grouping has an informative meaning. We'll see this better with the time signature. For now, just a glimpse at how beamed notes look.

You should have got the idea.

But, wait, what's that ♮ on the left of the last note? I haven't explicitly talked about that. It is the natural sign. It says that the note must be played natural, without “alteration”. Why do you need it in this case? There's a convention according to which if I write a, say, D#5, then future notes on the same line will be D#5 too, even if I omit the ♯.

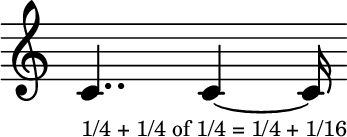

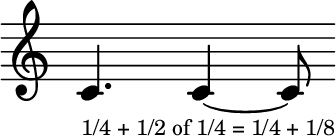

Back on duration. There's another notation which says that the duration of the note is what you've already learnt, plus half its duration. To say that you put a dot on the right of the notehead.

The upper staff shows the notation I am talking about; the lower staff shows a note whose duration is the sum of the dotted note plus the next note — notes are aligned so that e.g C4 of the lower staff begins when C4 of the upper staff begins, and ends when D4 of the upper staff ends (this is suggested by the alignment of the E4 on the lower staff).

I've tried to show the simple fact that 1/4 + half 1/4 (this is the meaning of the dotted quarter note) + 1/8 gives 1/2, that is a minim a.k.a. a half note, which is in fact the duration of the C4 on the lower staff.

It exists another notation: the double dot. This means you must add a quarter of the duration of the note it refers to.

I've added another notation! That “arch” between two notes of the same pitch (C4 in this example) means that they aren't actually two distinct sounds: it is a single sound played for the duration of the sum of the two tied notes — that sign is called tie. On a piano, it means you must not hit the key again. The duration of the dotted quarter note is the same as the duration of the tied notes. That is because of the definition of the double dot. These notations are equivalent, but the second one (the tied notes) is more versatile — we'll see why talking about measures.

The same holds for the single dot, of course:

These are the basic things to know about how standard musical notation “encodes” the duration of notes. There are few other notational things that impact on the duration of a note, but mostly they have to do with the details of the interpretation, and I won't talk about those here.

How long does a whole note last?

None of the things I've said so far about the duration of the notes tells us how long notes actually do last!

But of course it is enough you fix the duration of a specific note. E.g. if I say that a whole note lasts 1 second, the duration of all the other notes is fixed too: a half note lasts for half a second, a quarter note lasts 0.25 seconds and so on. Their absolute duration is consequential, because the notational duration of all notes is given by a known ratio with other notes' durations.

Tempo

Fixing the duration of a note, so that player will play a note for its intended duration, means to decide the tempo of your musical piece — that is, its “speed”. This is usually done in such a way that it is related to the meter, i.e. the rhythm structure, which you set with the time signature. I haven't talked of this important topic yet, but indeed you don't need to know it to understand how the tempo can be written in the notation.

An interesting thing is that tempo usually wasn't specified in a exact way; rather it was given in a general way, through names or expressions which suggested how fast or slow must our piece have been played. You are not required to give an exact duration for a specific note, after all.

Italian expressions were (are?) often used (even by foreign composers); in classical scores you can read largo (it's an adjective meaning wide, broad) for a slow tempo, or allegretto (“(a) little (bit) happy”, or something like that — I'm Italian and I can get the meaning of allegretto, but I don't know how to translate it in English) for a fast, but not too much, tempo; and so on. There are commonly accepted ranges — ranges, not values! — for those expressions, which are a lot! (There wasn't any standard: composer were and are free to use words to express their idea of the tempo of the piece, even “fast as if hunted by a drake”, if you want.)

In contemporary music you can find precise indications, but it doesn't mean that interpreters must stick with the pace the authors decided…

This way of giving an exact tempo is this: you say how many notes of a certain duration there are in a minute. You read it as bpm or beats per minute — to get why, again we need to introduce the time signature. But we can be very practical, because the notation is easy to be used and understood.

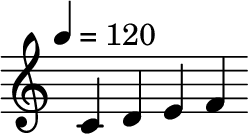

Here it is:

You read it so: there are 120 quarter notes in a minute. This fixes the absolute duration of a quarter note, hence all the other durations are fixed, too.

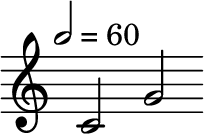

But you can also say this:

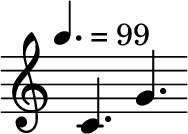

There are 60 half notes in a minute. But two quarter notes make a half note, so there are still 120 quarter notes in a minute. Why should we write the same tempo in this different ways? Beats per minute should make you think that the way you write the tempo is related to the rhythm: your are saying how many beat “accents” there are in a minute. Nonetheless, you could interpret it as a more generic way of specifying the absolute duration of a note. You can also use dotted notes:

This is useful when your “accents” happen every three eighth notes (in this example).

So, how long does a quarter note is? You need a little bit of math, if you really care about the value in seconds: e.g. 120 quarter notes in a minute are 120 quarter notes in 60 seconds, so each quarter note must last half a second. Similar math for the other cases.

Instead of math, you usually will use a metronome to keep the pace, and your natural skills will help you to keep the rhythm (almost) constant while you play, at least after you trained yourself properly. A metronome can be set so to produce short sounds (clicks) at the specified interval — not by chance you specify this interval as bpm, and the way the metronome is built or programmed does all the needed math for the correct timing.

There exist mechanical and digital metronomes. Your computer or your mobile phone can act as a metronome with the proper software. If you search “metronome” on Google, you'll have a ready-to-use metronome in your browser!

(Image credit: Google searching metronome)

Of course tempo can change during a piece, though usually most pop songs keep the same tempo. There's a way to say that the tempo changes gradually, making the pace of the song faster or slower. When it changes abruptly, you simply put another tempo mark, something like this:

Indeed these abrupt tempo changes will happen often on some kind of mark which makes unambiguous the interpretation of when the change really happens.

Jump to the 4th lesson (this link will be valid when I will publish the 4th lesson).

Index of the lessons so far (the current one excluded)

- Lesson 1: basic knowledge about sound.

- Lesson 2: dissonance, consonance, tuning, 12-tones equal temperament, notes' names and notes on a staff, treble and bass clefs.

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.