Xinta's music lessons - Lesson 5

In the previous lesson we started to talk about scales and I've shown the key signature notation and the circle of fifths.

When we've talked also about enharmonics in lesson 3. So we know that, in the 12-tones equal temperament on which most of the western music is based on, there are notes that has different notation, but are indeed the same:

| C♯ | D♯ | F♯ | G♯ | A♯ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D♭ | E♭ | G♭ | A♭ | B♭ |

But there are also these:

| E♯ | B♯ | B | E |

|---|---|---|---|

| F | C | C♭ | F♭ |

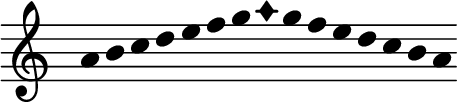

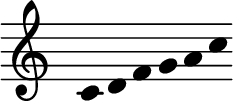

The same happens with key signatures. Let's reconsider B♭ minor (I won't specify natural anymore), with its five flats. Let's build the A♯ minor scale. Here's the notes:

You can begin with the already given B♭ minor scale and write the notes enharmonically with sharps, or rather you could think like this: I know the A minor scale, if I raise it by a semitone, I must obtain the A♯ minor scale. Since the A minor scale has no accidentals, when you raise it by a semitone, which is what the sharp symbol does, you'll have all the notes with the sharp symbol. This is one of the cases when you won't write E♯ as F or B♯ as C, because you would make the scale less intellegible. (Also remember that enharmonics exist because of the 12-tones equal temperament, but it hasn't to be so universally.)

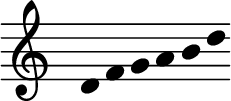

The key signature for A♯ minor is enharmonic to the key signature for B♭ minor. The notes are notated differently:

But they play the same pitches.

Despite the notation, if you play those notes, you will hear the same scale repeated two times.

Now let's continue our trip among scales.

Degrees of a scale

Each note of a scale can be addressed in a general way. Instead of first note, second note, third note, and so on, you call it first degree (of the scale), second degree (of the scale), third degree (of the scale) and so on. Moreover, each degree of a heptatonic scale has a name, which talks about its role in the harmony.

- 1st degree, tonic, the key or root note: the center of tonality — think of it as a center of gravity;

- 2nd degree, supertonic;

- 3rd degree, mediant;

- 4th degree, subdominant;

- 5th degree, dominant;

- 6th degree, submediant;

- 7th degree, leading note/tone, or subtonic (see below);

- 8th degree, the tonic again, one octave above.

About the double name of the 7th degree: leading note (or leading tone) is used in major scales; it's a sound that when played (in a context when the tonality is already clearly expressed), makes you “desire” to hear the tonic (in an ascending “jump” of a semitone). In a natural minor scale it's called subtonic, the note below the tonic by a whole tone (I've also heard subtonic used for a major scale, as if sub-tonic iwere just the note below the tonic, by definition). The 7th degree in the natural minor scale doesn't make you “desire” the tonic so strongly as in a major scale; hence the name subtonic tells just about its position with respect to the tonic, while the name leading tone highlights the “function” of a leader driving to the center of tonality — we say that it resolves (ascending) to the tonic. This feature is bound to the semitone interval between the leading note and the above tonic.

Honestly I tend to use the ordinal numbers instead of the names, except for tonic, subdominant, dominant and leading note (which is called “sensibile” in Italian). Moreover, when dealing with scales with less or more than seven notes, you'll likely stick to ordinal numbers anyway, even though you can use those names to stress a role; in particular, for tonal music, you'll still use tonic for the note which is the center of tonality. And also leading note is a name you can use for other degrees with such a role.

Melodic and harmonic (ascending) minor scales

We've seen the natural minor (ascending) scale, but there exist also the harmonic minor and melodic minor scale. These are heptatonic scales (they have seven notes) as well, but they are not diatonic scales.

I'm going to use the A as the root note. Using what you've learned from the previous lesson, you can apply the same idea on scales with other root notes.

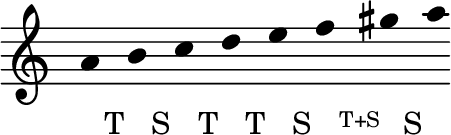

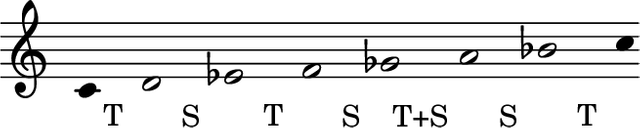

The harmonic minor scale has the seventh degree raised by a semitone. In this way, the interval between the seventh note and the tonic of the scale at the next octave is a semitone, as it is in a major scale — so that the harmonic minor scale has its leading note. In the same time, the interval between the sixth degree and the seventh degree, which was a Tone (TSTTSTT), becomes a tone plus a semitone (T+S).

When you play the G♯ followed by the tonic A, the effect is the same as what you have with a major scale, which in fact has a semitone as last interval. The natural minor scale hasn't the leading note, i.e. a seventh degree with such a strong affinity to the tonic that it needs to resolve ascending to it and giving “relief” and a sense of conclusion. The harmonic scale “solves” this lack, so to speak. But it creates a problem: the interval between the sixth and the seventh degree is now made of three semitones (the name of this interval is augmented second, but we'll see this later).

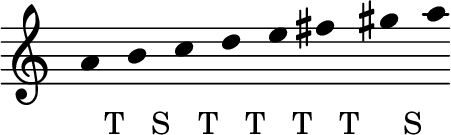

An augmented second could sound ugly, not too much melodic, and anyway likely isn't what you want. What if we raise also the sixth degree? We obtain the melodic minor scale, which hasn't the augmented second anymore, but it still has the desiderable property of the seventh which ascend to the tonic with a semitone.

Descending scales

We've seen so far ascending scales. A descending scale is nothing but a scale which starts from a note and goes downward. The pattern Tones-Semitones for a descending major scale is a reversed ascending major scale pattern:

- TTSTTTS ⟶ STTTSTT

It's not very much different for the natural minor scale:

- TSTTSTT ⟶ TTSTTST

And for any other scale: just begin with a note and go downward instead of upward. There's a subtlety, though. Some scale may have certain notes when ascending, and others when descending. It's the case of the melodic minor scale, which when descending is, de facto the natural minor scale.

This turns to be useful in melodic passages, especially if you want to avoid the 7th degree strong affinity to reach (ascending) the tonic, which isn't a desired property if your melody “need” to go down.

Anyway you can use also the descending melodic minor scale as it is; if it works for the major scale, why shouldn't it work for the melodic minor? Likely you will avoid that descending movement from tonic in your melody.

Roller coasters!

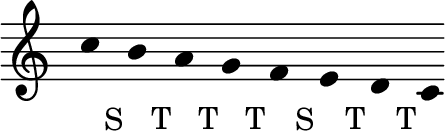

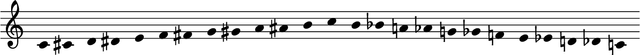

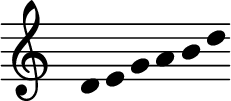

Let's ascend and then descend!

Why? Just to make you notice the simmetry around the “pivotal” root note (with the highest pitch). If you “rotate” the score around a vertical axis passing on that pivotal note, you still have the same musical score (consider the clef a fixed part).

It is something useful? Not now, maybe, but you could discover soon or later (likely not in these lessons) that similar simmetries can be exploited to build melodies with interesting properties — in this example, if you play it from left to right, or from right to left, you obtain the same melody.

Blues heptatonic scale

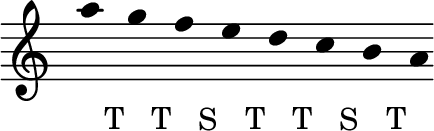

This is another scale with seven notes and it's one of the scales used by the genre of music called blues.

Compare it with the ascending natural minor scale:

Chromatic scale

A scale which uses all the 12 notes is a chromatic scale. When asceding, we'll use sharps, when descending we'll use flats. As usual, you can build a chromatic scale beginning at any pitch. In this case the interval between adjoining notes is always a semitone, so the only thing that changes when you begin with different notes, is the pitch.

Because there isn't a repeated (in several octaves) pattern of Tones-Semitones, it is hard to use this scale to state a center of tonality. Its usage and the fact that it has all the notes, give birth to something like dodecaphony; if there isn't a note which is more important than another, i.e. none of the 12 notes is the “tonic”, then the music will be atonal. To give a form to the musical materials, you need something which is not tonality, that's it. Schönberg is the father of dodecaphony.

Hexatonic scales

A hexatonic scale is a scale with six notes. As long as the notes are six, you can call it a hexatonic scale, of course. But how are those notes “distributed”?

The whole tone scale is one of the possible hexatonic scales.

We have 12 semitones in an octave; if we “pair” them, we obtain 6 tones, hence six notes. As usual we can build our scale starting from a specific note, the first degree. You will see that there are two complementary whole tone scales. Complementary means that the two scales don't share any pitch. Altogether they give all the 12 notes of the octave.

These two scales are:

and

The whole tone scales suffer a similar “problem” to the chromatic scale, in that all the notes are an equal interval (a whole tone) far from their adjoins, and also a similar “problem” to the natural minor scale, in that they lack of a leading note.

Other hexatonic scales exist, but the whole tone scale is likely the most known, altogether with the blues hexatonic scale.

Pentatonic scale

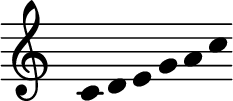

A pentatonic scale is a scale made of 5 notes.

There are many pentatonic scales. You can take a heptatonic scale and delete two notes; for example consider a major scale and delete the 4th and 7th degree; doing so, the larger interval will be T+S, the smaller will be T.

There are no semitones, and this is why this kind of scale is called anhemitonic (a- means without, hemi- is a prefix meaning half, so that the word means “without half tones”, i.e. without semitones). Of course this is not the only possible pentatonic scale with this feature.

You can remove the 3rd and 7th degree:

This scale is anhemitonic, too. Let's remove the 1st instead of the 7th (in the examples I'm considering the C major scale):

And now let's remove again the 4th instead of the 3rd:

Let's see another pentatonic scale. Do you remember the black keys of a piano? They are five, and so you can make a pentatonic scale made only of those notes.

But if you look at it carefully, you will notice that it's nothing but a scale we've already seen, but transposed a semitone up.

Guitar strings are usually six, and they are tuned to produce (when pplucked free) E, A, D, G, B, E. If you ignore one of the E and sort them properly (D, E, G, A, B) you have a pentatonic scale we've already seen above.

Let's build a pentatonic scale with a semitone (hemitonic). To do this, let's take the 12 semitones of an octave.

S S S S S S S S S S S S

A semitone is an interval, the distance between a note and another. Just to fix the idea, let's “anchor” the sequence of semitones to the root note C.

S S S S S S S S S S S S

C C

The distance between C and the C of the next octave is 12 semitones — you should already have this hardcoded in your brain! Now, let's place the D. It is 2 semitones up from C. So

S S S S S S S S S S S S

C D C

And so on. This is just a way to show how many semitones there are between two notes.

Since the “anchor note” isn't important, I will replace it with a x. I will replace all the notes with x as a placeholder. We are interested in the intervals between the x-es, so that, starting from any note (e.g. C or G) we can build our scale. As it was with the more common heptatonic major and minor scales, the quality, so to speak, of the scale is given by the alternation of the intervals, by the pattern, not by the notes for themselves. In fact, given the previous pentatonic scales, you can transpose them to obtain other scales with different “root note”, but the very same pattern of intervals — hence they are the same, even if at a different pitch.

The representation I am using should help us to build our pattern; we “move” the x-es so to make the distance between them different. The first x (and the last, which is the same note) stay put: the first is our anchor, our fixed point from which we are measuring the distance — and the last one is our target, the octave. We put five x-es plus one, because we're building pentatonic scales.

The following is a way of distributing our notes (x-es)

S S S S S S S S S S S S

x x x x x x

We have one whole Tone (2 semitones), three T+S, and one semitone — hence this will be a hemitonic pentatonic scale. Now we fix the “anchor” note, so that we can show the scale.

Another example:

S S S S S S S S S S S S

x x x x x x

A less improbable hemitonic pentatonic scale could be the following, with the largest interval of two whole tones.

S S S S S S S S S S S S

x x x x x

Intervals

At this point you should have clear the fact that an interval is a “distance” between a note and another. You can measure it in semitones and tones, or semitones only. Specific intervals has specific property from the point of view of harmony (when notes are played simultaneously), but are important in a melody (when notes are played one after another), since in fact the succession of intervals makes the melody distinctive, altogether with the duration of each note.

Intervals have specific names, too. We've already seen the octave (12 semitones), the unison (same note), the augmented second (3 semitones), and also the fifth, even though I haven't specified its quality.

I list the intervals: their names, their extents, a common way to refer to that interval in short. An interval (a “distance” of a certain number of semitones) can be interpreted in different ways; this is why the “extent” doesn't increase at each row. In the next lesson we'll be back on intervals, just to know the matter a little bit better. Then I'll use the intervals according to the needs of the lessons.

Keep in mind the degrees of the ascending major and minor scales (if I don't specify more, I am talking about heptatonic scales), you will notice there's a relationship.

| extent | name | abbreviation |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | perfect unison | P1 |

| 1 | minor second | m2, min2 |

| 1 | augmented unison | A1, aug1 |

| 2 | major second | M2, maj2 |

| 2 | diminished third | d3, dim3 |

| 3 | minor third | m3, min3 |

| 3 | augmented second | A2, aug2 |

| 4 | major third | M3, maj3 |

| 4 | diminished fourth | d4, dim4 |

| 5 | perfect fourth | P4 |

| 5 | augmented third | A3, aug3 |

| 6 | diminished fifth | d5, dim5 |

| 6 | augmented fourth | A4, aug4 |

| 7 | perfect fifth | P5 |

| 7 | diminished sixth | d6, dim6 |

| 8 | minor sixth | m6, min6 |

| 8 | augmented fifth | A5, aug5 |

| 9 | major sixth | M6, maj6 |

| 9 | diminished seventh | d7, dim7 |

| 10 | minor seventh | m7, min7 |

| 10 | augmented sixth | A6, aug6 |

| 11 | major seventh | M7, maj7 |

| 11 | diminished octave | d8, dim8 |

| 12 | perfect octave | P8 |

| 12 | augmented seventh | A7, aug7 |

We can have distance greater than 12 semitones. In this case you can just start over (subtracting 12 from the distance in semitones). Or continue like this:

| extent | name | abbreviation |

|---|---|---|

| 13, 1 | minor ninth | m9, min9 |

| 13, 1 | augmented octave | A8, aug8 |

| 14, 2 | major ninth | M9, maj9 |

| 14, 2 | diminished tenth | d10, dim10 |

| 15, 3 | minor tenth | m10, min10 |

| 15, 3 | augmented ninth | A9, aug9 |

And so on. I hope you've got the “game”, anyway I will talk about intervals more in future lessons.

Index of the lessons so far (the current one included)

- Lesson 1: basic knowledge about sound.

- Lesson 2: dissonance, consonance, tuning, 12-tones equal temperament, notes' names and notes on a staff, treble and bass clefs.

- Lesson 3: semitones, duration, beaming, tempo.

- Lesson 4: time signature, downbeat, upbeat, rests, ascending major and natural minor diatonic scales, key signature, circle of fifths.

- Lesson 5: scale degrees, more scales, intervals.

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

I'm surprised you didn't include anything about the diatonic modes. I've been planning to make an article about those for a while. Are you planning on doing something about those in the future? It could perhaps be a lesson. "Lesson 6: The Diatonic Modes." I might do one as well (but not a lesson series, just a fun fact article like I did about solféggio). Anyway, this was a well written article!

Purposely I won't talk about modes, not in this “layer” of lessons, which have no focus on modality in general, except for those modes that are, in fact, the major and minor scales. Nonetheless, in the previous lesson I've dropped clues about the existence of modes and gave also a couple of pointers. My plan doesn't include modality in depth, though maybe I could have listed the diatonic modes, at least. The correct place should have been the previous lesson. I could resume the argument when and if I will talk about musical genres like jazz, or put them in an addendum/appendix to complete that part of Lesson 4 where I mentioned the Dorian mode; I could also list them in the next lesson, but this was on intervals, so I need an excuse to be back on that topic. Thinking about it…

Thank you for the feedback and the suggestions!

This is very nice, and quite detailed. Great job!

Thank you!