Xinta's music lessons - Lesson 6

Let's see intervals and their “nomenclature“ from the point of view of a diatonic scale degrees, which should give a meaning to the “nomenclature” itself, as you maybe have already deduced at the end of the previous lesson (that's what I referred to as “game”). This makes more sense than counting semitones alone, even if those intervals with the same “extent” in semitones are enharmonic. In the previous lesson we've seen that even if E♯ is the same key (on a piano) of F, you will still write it as E♯ and not as F: they are logically different (indeed this ambiguity can be exploited, but we'll see this in a future lesson). It holds for intervals, too.

| Degree | quality | abbreviation | extent |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | perfect | P1 | 0 |

| augmented | aug1 | 1 | |

| 2 | diminished | dim2 | 0 |

| minor | min2 | 1 | |

| major | maj2 | 2 | |

| augmented | aug2 | 3 | |

| 3 | diminished | dim3 | 2 |

| minor | min3 | 3 | |

| major | maj3 | 4 | |

| augmented | aug3 | 5 | |

| 4 | diminished | dim4 | 4 |

| perfect | P4 | 5 | |

| augmented | aug4 | 6 | |

| 5 | diminished | dim5 | 6 |

| perfect | P5 | 7 | |

| augmented | aug5 | 8 | |

| 6 | diminished | dim6 | 7 |

| minor | min6 | 8 | |

| major | maj6 | 9 | |

| augmented | aug6 | 10 | |

| 7 | diminished | dim7 | 9 |

| minor | min7 | 10 | |

| major | maj7 | 11 | |

| augmented | aug7 | 12 | |

| 8 | diminished | dim8 | 11 |

| perfect | P8 | 12 | |

| augmented | aug8 | 13 |

We have the seven degrees of an heptatonic scale, with the 8th degree being the octave (the tonic again). We can continue as we did when we focused on semitones.

| Degree | quality | abbreviation | extent | simple interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9 | diminished | dim9 | 12 | 2 |

| minor | min9 | 13 | ||

| major | maj9 | 14 | ||

| augmented | aug9 | 15 | ||

| 10 | diminished | dim10 | 14 | 3 |

| minor | min10 | 15 | ||

| major | maj10 | 16 | ||

| augmented | aug10 | 17 | ||

| 11 | diminished | dim11 | 16 | 4 |

| perfect | P11 | 17 | ||

| augmented | aug11 | 18 | ||

| 12 | diminished | dim12 | 18 | 5 |

| perfect | P12 | 19 | ||

| augmented | aug12 | 20 | ||

| 13 | diminished | dim13 | 19 | 6 |

| minor | min13 | 20 | ||

| major | maj13 | 21 | ||

| augmented | aug13 | 22 |

If you go on, you will hit the 15th degree, which is again the tonic, two octaves up.

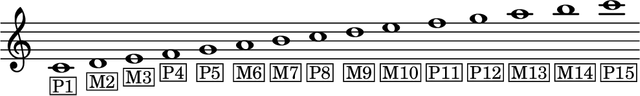

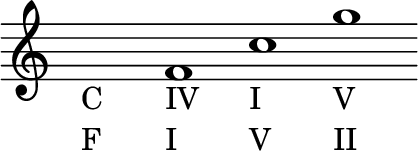

Let's show some of our intervals on a C major scale.

A note alone of course doesn't determine an interval. So here the reference “point” is always the root note of the scale, the tonic: in the previous score you must imply the reference to the 1st degree, C.

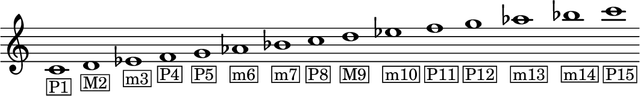

The scale is a C major scale, and you can see why some intervals are major. Nonetheless, let's try with the C natural minor scale.

You see that the interval between the tonic and the second degree is still called major, but third, sixth and seventh are minor, but they are major if you consider the ascending melodic minor scale, so that only the third degree is distinctive.

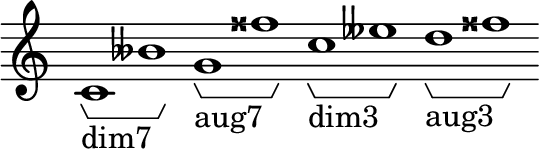

About augmented and diminished intervals, because they differ by a semitone from the perfect, minor or major quality, you will use sharps and flats. What if there's already the same accidental on the note? Let's meet double flat 𝄫 and double sharp 𝄪.

Melody, intervals, frequency

In a melody, the note which is playing “walks” from a pitch to another, or stay the same. You can describe these movements through intervals. These movements are called step when the interval is the one you find between two adjoin scale degrees. Otherwise it is called skip, jump or leap.

When a melody proceeds mainly “step by step”, we talk of conjuct melodic motion, otherwise (if the melody contains many skips) of disjunct melodic motion.

An example of conjuct melodic motion could be the most famous theme of the 9th symphony by Beethoven, the so called Ode to the joy.

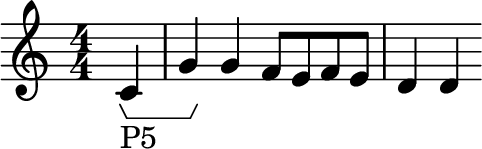

Even if the Top Gun Anthem begins with a skip (a perfect fifth) and contains also a major third skip, it can be counted as another example of conjuct melodic motion.

An example of a melody which proceeds jumping can be taken from Beethoven's begin of the 3rd symphony, first movement.

If you take one of these melody and transpose them up, or down, you will be able to recognize them: the intervals between notes as the melody proceeds, are the same. At least by name. What about frequency? Let's consider the octave. We know that if the note we are playing has frequency f, the same note one octave up has frequency 2f. That is, the extent of the octave is, in term of frequency, 2f - f, i.e. f. But f changes according to the note we considered first. It could be 440 Hz for A4, but if could also be 880 Hz for A5, and this means that the octave is 440 Hz but also 880 Hz wide! The higher the frequency, the “larger” the interval in term of frequency.

Nonetheless, human hear perceives the two jumps, one of 440 Hz (from A4 to A5) and the other of 880 Hz (from A5 to A6) as being of the same extent: human hear perceives intervals logarithmically.

This also means that, if we consider distances between the notes of an octave in frequency, lower frequencies have a greater “density” than higher frequencies. This explains why, if you play chords with low pitches, they sound “harsh”.

Harmony, intervals, chords

Chords? What?

When you play two (or more) notes in the same time instead of one after another, that is, you play them simultaneously instead of sequencially as you do when you play a melody, you have a chord. A chord can be made of two or more notes and the intervals between these notes determine the “character” of the chord.

When notes are combined together we talk of harmony. Specific intervals “combined” together and successions of chords give specific “feelings”, which you can learn studying the rules of harmony. When the focus isn't on the simultaneous aspect of the notes read vertically, but rather on the way two or more melodic lines combine, a harmony is perceived anyway, but the matter that tames this plot is called counterpoint.

In these lessons I talk about harmony and the rules that can guide you to use it to compose music — quite a ambitious purpose, specially because harmony is just one of the thing you should master to compose knowingly (likely many of you know that you can make music without a formal knowledge and understanding of the whys and notational hows). All the lessons you've read so far were an introduction, sort of, to this key argument.

The word “rules” makes you think about mechanical thing — so, where's the art? Think about human languages: they obey rules, and a text uses also recognizable patterns, figure of speech and references to the cultural elements around us, things that we know because we are submerged in our culture. And we feel comfortable when we can spot cultural tropes, even if unconsciously. Despite the rules that you must obey to make your text intelligible, you can produce infinite (almost…) amount of literature. And you can also break some rules, now and then, just to obtain some kind of desidered (artistic) effect or to express something you believe you can't express differently…

Something similar holds for the music, even though it's a different kind of language. We have already mentioned in lesson two that two (or more) sounds together can be consonant or dissonant (and give “tension”), and this is a conseguence of the physical, psychological and cultural aspects of sound.

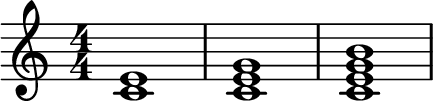

The notation to say that two (or more) notes play together is easy and intuitive: you just put the notes vertically.

The score shows three chords made of two, three, and four notes. Because harmony deals with how notes play together, we can disregard completely the rhythm; that's a reason why we use long notes like semibreves (whole notes) or minims (half notes) — also because we want to suggest that we “need” to hear how those sounds play together, so we need them to last enough.

Since the second lesson, you can imagine already that if you take notes whose pitches (its the fundamental harmonic) coincide with the first (stronger) harmonics of another lower sound, all those notes together play “well” (of course all their harmonics are “mixed”).

Let's consider C1. You can compute its frequency (according to 12-tones equal temperament) starting from a reference frequency and multiplying (or dividing) by the 12th root of 2 (i.e. raising or lowering the pitch by a semitone). With A4 = 440Hz, we have: A3 = 220Hz, A2 = 110Hz, A1 = 55 Hz, A0 = 27.5 Hz. The interval between any A and the C on the above octave is a minor third (at this point you should be able to check it by yourself!), 3 semitones, so we must multiply 27.5 Hz by 23/12: ≅32.703 Hz (it's enough to keep only three digits after the point).

Here's the table of the harmonics of C1, their frequency, the nearest note (according to the 12-tone equal temperament) and the difference, expressed in cent rounded to the nearest integer, between the harmonic's frequency and the frequency of the 12-tone equally tempered note (i.e. you have to add algebrically the number in the “difference” column to obtain the frequency of the note in the 12-tone equal temperament). One hundred cents (100 cents) make a semitone.

| harmonic | freq | nearest note | difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 32.703 | C1 | 0 |

| 2 | 65.406 | C2 | 0 |

| 3 | 98.110 | G2 | -2 |

| 4 | 130.813 | C3 | 0 |

| 5 | 163.516 | E3 | +14 |

| 6 | 196.219 | G3 | -2 |

| 7 | 228.922 | B3♭ | +31 |

| 8 | 261.626 | C4 | 0 |

If you consider only the first three different notes, you have C, E, G (sorted). And here it comes a chord with C as its funtamental note. The interval between C and E (in the same octave) is a major third, and the chord is called C major. If you consider also the first different fourth note (B♭), you have a chord made of four notes, i.e. a four-notes chord, that is a three-notes chord with the minor seventh (that is, adding the note which forms the interval min7 with the fundamental sound, C in these example); in fact it's also called a seventh chord.

If you consider the scale starting from the fundamental sound, and count the degrees, you see that a triad (a three-notes chord) is made of the fundamental or root note, plus the 3rd and the 5th. The 3rd determines if the chord is major (when the interval is a major 3rd) or minor (when the interval is a minor 3rd). There are several ways to call triads in brief. E.g. C is the C major triad, while Cm is the C minor triad; C7 is the seventh chord where we have the min7 interval, as said before, but Cmaj7 could be the name of the four-notes chord with then maj7 instead of min7. While writing music other conventions may exist, according to different genres. Tipically we see such short names for chords in pop music, because classical music usually doesn't need to write chords like Cmaj7: you write the notes and that's all.

Triads on major and minor scales

We have seen above why we consider certain notes rather than others in a triad. Triads can be thought of as made of the superposition of two intervals. The quality of the third determines if we have a minor or major chord. The fifth is perfect, and in this way our triad is “pleasant”.

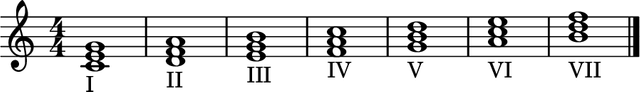

Let's see the triads we can build on the C major scale. Of course the same holds for any other heptatonic major scale.

For each degree, denoted with a roman numeral (which is a standard way to denote degrees) we add two notes whose intervals with the root note are a third and a fifth. Then we will analyse the quality of these intervals.

Using the knowledge about intervals, you should be able to do the following table by yourself.

| degree | quality of the 3rd | quality of the 5th |

|---|---|---|

| I | major | perfect |

| II | minor | perfect |

| III | minor | perfect |

| IV | major | perfect |

| V | major | perfect |

| VI | minor | perfect |

| VII | minor | diminished |

All the triads on a major scale are major or minor, and they have a perfect fifth, except for the triad on the VII, which has a diminished fifth. Because of this diminished fifth, this is a dissonant triad containing the leading tone of the scale as root note. This dissonance wants to be resolved, someway.

You can describe the perfect fifth as made of the sum of two smaller intervals, namely a major third and a minor third. In fact you can see that on degree from Ⅰ to Ⅵ this “pattern” is respected: on Ⅰ, we have a major 3rd followed by a minor, on Ⅱ we have a minor followed by a major 3rd, and so on. Exception: the Ⅶ, where we have two minor 3rd, and in fact the result is a diminished fifth interval.

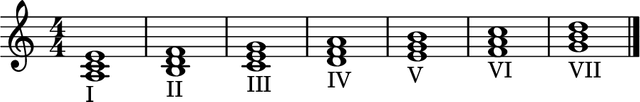

Let's make something similar on a natural minor scale.

The triads are the same, of course; this time the diminished fifth is on Ⅱ. You can build a table similar to the one above.

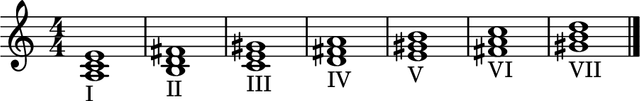

Let's see the melodic minor scale.

| degree | quality of the 3rd | quality of the 5th |

|---|---|---|

| I | minor | perfect |

| II | minor | perfect |

| III | major | augmented |

| IV | major | perfect |

| V | major | perfect |

| VI | minor | diminished |

| VII | minor | diminished |

Affirming the tonality

The triad on the tonic — the first degree of the scale, Ⅰ — is a chord that someway affirms the tonality; so it is a very important chord. Every major or minor chord (with a perfect fifth) can assume the role. So, what's the difference between, say, C major and G major?

The difference is in when they appear and how they are used. Harmony, as steps and skips in a melody or the patterns in scales, is “hooked” to a starting point. The first chord you play in your musical piece affirms the tonality. Almost… Likely… It depends on how it proceeds; the center can be “moved” (the tonality can be changed, and this is called modulation), and you maybe have started your piece in such a way to deceive the listeners, to confuse them and so to surprise them. In general, to produce an artistic effect.

E.g. we've seen that the chords of the tonality of C major are the same of those of A minor (every major scale “contains” also a minor scale, and so the chords on its degrees are the same; we say that A minor is the relative minor of C major, see also the circle of fifth in the lesson 4). So you could play an A minor chord first, but then start using the chords as if they were chords of C major. That would be odd (especially if you do it without a clue), but it's feasible.

Tonality can be changed (modulation), nonetheless a lot of music doesn't change it, not even temporarily (temporary changes are more common). Usually you pick a tonality and keep it — except when you want to try modulation — or anyway you write your music in such a way that it can be thought as related to that main key. In classical music, compositions may be called like this: Symphony No. 3 in E♭ major by Ludwig van Beethoven. This doesn't mean that each movement must be in this key (e.g. the 2nd movement is in C minor, but this is the relative minor of E♭ major…), or that each note of the same movement belongs to that key: e.g. in the very beginning of the first movement there's a C♯, an augmented sixth, with respect to the E♭ major scale, but it is also the subtonic of the D♯ minor, which enharmonically is the E♭ minor.

Anyway…

How do you affirm the tonality? The first chord will be the triad on the Ⅰ. Then you will use the chords on other degrees in such a way that they help this statement. The chords will belong to the tonality, dissonance (and other “tricks”) will be used to give tension, so that our piece won't be “soft” or boring, and then to drive to the tonic again. As far as we are concerned here, the usage of the chords after the first is “pinned” to the first.

After the Ⅰ, there are two other very important triads: the one built on the V and the one built on the IV. You can write a whole song with only these three chords (indeed, you can write a song also using only Ⅰ and V…! But also only Ⅰ, if you want…).

The importance of the V can be explained like this: the fifth is the first harmonic which is not the fundamental. Moreover, the triad contains the leading tone of a major scale (or of a melodic or harmonic minor scale), which “calls” for the tonic (once you have affirmed clearly which is the tonic!)

The importance of the IV can be explained like this: its fifth is our tonic. The relationship between F and C is the same of the one between C and G. In the C major key (we can write it simply as C), F is the IV, while in F major key (F), C is the V.

The chords built on Ⅰ, Ⅳ and Ⅴ are the main “character” of very common and important harmonic cadences. These can be used to give the sense of “accomplishment” to a musical passage or piece. You are surely familiar with the classical “closing” cadence, the one you hear at the end of many pieces and that makes you think that it's in fact finished. This is something like V-I or IV-V-I.

Don't worry about it now, there will be room for cadences (and other subjects) in future lessons.

Still a chord

Even if a chords as we want to study in harmony is “simultaneous” in nature, this doesn't mean you can't “feel” a chord when in fact not all notes are played simultaneously. Strumming a guitar produces a chord, but each note doesn't begin in the exact instant — this is always true, because performers aren't robots (except when they are indeed robots or computers, of course), but in the guitar, or in general string instruments when played strumming, the time difference is larger, even in the fastest strumming, and you can notice it.

You can pick strings one after another and this makes you hear that chord. Sure, the fact that the strings continue vibrating helps, but if you stop them after the pick, you obtain a sequence of notes that are the notes of a chord (which one depends on where your fingers press each strings against the fretboard). It is easier to recognize it if the notes have a short duration, but it holds true even for longer notes.

I am talking about broken chords and arpeggio: notes of a chord aren't played “stacked” but sequencially, one after another, instead. The following examples use this “device” to express the C major triad.

Melodies can be made this way, too; so that they can be considered as a melodic line, but in the same time this melodic line is made only of notes of a chord, so that the listener “feels” it. I've already shown an example:

The B♭ appears at two different octave and when it appears the first time, it is lower than the root note of the chord (E♭). If you put all the notes together in the upper tiny staff, you might think that I've missed a note, i.e. this lower B♭. It is not (only) because I wanted to use triad without repeating notes, but because chords sound differently if you don't keep the root note as the lower note. We shall see this in the next lesson.

Dorian mode and “siblings”

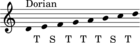

While you are ruminating over all I've written above, let's take a pause and step back to the lesson 4. I've mentioned Gregorian mode and Dorian mode, with the pattern TSTTTST.

We were building diatonic scales starting from every possible “white note”, even if I stopped and focused on those patterns which gave the major and minor scales, so widely used in so many compositions.

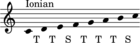

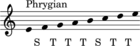

Let's resume this activity. Each pattern tones-semitones we obtain get a Greek conventional name, but there isn't a strong relationship with ancient Greek modes (which should be the ancestors of all this thing, anyway).

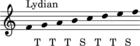

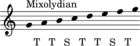

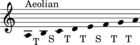

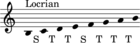

| Mode | degree | pattern | remarks | example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ionian | I | TTSTTTS | major mode |  |

| Dorian | II | TSTTTST |  | |

| Phrygian | III | STTTSTT |  | |

| Lydian | IV | TTTSTTS |  | |

| Mixolydian | V | TTSTTST |  | |

| Aeolian | VI | TSTTSTT | minor mode |  |

| Locrian | VII | STTSTTT |  |

The Ionian mode coincides with the major scale we've already seen, and the Aeolian mode coincides with the natural minor scale.

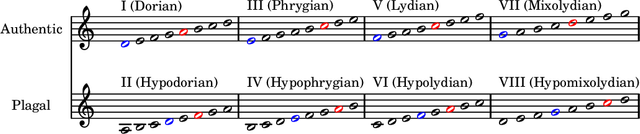

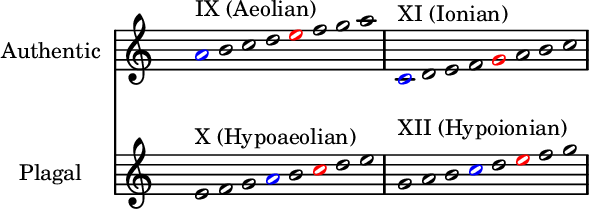

Shortly, a little bit of quick and incomplete notions about Gregorian modes (church modes), typically used in Gregorian chant: they might be 8 or maybe 12 (it depends on the epoch and theorists); they get Greek names, or just numeral numbers, if you prefer; they are classified in two “groups”, authentic modes and plagal modes, so that for each authentic mode there's a plagal “companion”, and viceversa; they have a final — a note on which the chant ends — and a dominant (or cofinal) — a note where the chant can rest; finals are the same in each pair of authentic-plagal modes, while dominant in each plagal mode a third down the dominant in its authentic companion, except when this is B — in this case it is a second down. In the authentic modes, dominants are on the fifth degree of the scale, except when this is B; in this case it is on the sixth.

In those past times the notation was very different, but here we use the modern notation; the final is colored in blue, the dominant in red.

Here they are, eight Gregorian modes:

And here there are the remaining four:

The names for the plagal modes are the same of the authentic “companion” but prefixed with hypo- (if you consider mixo- as a prefix, then the lydian name with or without prefixes “labels” a total of four modes). Each plagal mode is a fourth below its related authentic mode, and this is why there are modes that, if considered only as scales, are repeated.

Hypomixolidian mode is the same as the dorian mode, except for the final (and dominant); hypolydian is the same as the ionian, but again has different final (and dominant); mixolydian is the same of hypoionian, but final (and dominant) are different…

You can see that, if you intend the Gregorian modes just like “static” scales and disregard finals and dominants, then they are completely included in the diatonic modes. But they are not “static” scales, they embed, so to speak, the way the melody will be built around the final (and dominant). Gregorian modes are those used in Gregorian chant, sacred music which is typically monophonic. It's a sort of sung prayer. (Example: Gregorian Chants from Assisi).

An example of a classical composition which indulges in modal inflections is the Mussorgsky's Pictures at an Exhibition, which I like very much especially in the famous orchestration made by Maurice Ravel (the original is for piano). It's also an example of unusual metrics; here's the Promenade theme:

And so on. It goes on alternating 5/4 and 6/4. (The extra symbols suggest how to play the notes one after another. See articulation; here we have notes to be played tenuto — the line on the note's head — and legato — indicated by the slur.)

In case you are curious, on YouTube you can find several performance of the the Ravel's orchestration, and piano versions as well.

Index of the lessons so far (the current one included)

- Lesson 1: basic knowledge about sound.

- Lesson 2: dissonance, consonance, tuning, 12-tones equal temperament, notes' names and notes on a staff, treble and bass clefs.

- Lesson 3: semitones, duration, beaming, tempo.

- Lesson 4: time signature, downbeat, upbeat, rests, ascending major and natural minor diatonic scales, key signature, circle of fifths.

- Lesson 5: scale degrees, more scales, intervals.

- Lesson 6: intervals, harmony, triads, tonality, diatonic modes, Gregorian modes.

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.