Xinta's music lessons - Lesson 4

In the previous lessons you've learned what a staff is made of five lines; you've learned that clefs give meanings to those lines and gaps between them, so that once you've put a clef, the position of a notehead and an eventual accompaining accidental (we've seen so far the most common sharp, flat and natural signs) specify the pitch of the note. You've learned that the aspect of the notehead (solid or hollow), altogether with the presence or absence of a stem and flags, determine the relative duration of a note. You've learned that the absolute duration of a note is fixed once you choose the tempo of your piece.

Now it's time to talk about… time signature.

Time signature

Despite the name, the time signature doesn't say the “time”: we've seen that the absolute durations of the notes is given by the tempo, and this absolute duration will determine how much time will pass from when you start playing upto when you finish, provided that you respect it exactly (and you're not required to, though likely you usually don't want to play too slow a piece that should be played fast, or viceversa).

The time signature is also called meter signature, a more appropriate name. In fact it specifies the meter (or metre), i.e. the rhythmic structure of your piece. This rhytmic structure is given by a (repeating) pattern of accents, which (usually…) coincide with the beat; so each metronome click (which happens on a beat) has its accent, which can be stronger or weaker.

An accented beat is called downbeat, while an unaccented (unstressed) beat is called upbeat. Downbeats and upbeats come one after another in specific (repeating) pattern(s). The fact that the pattern is repeating contributes to make you feel a specific rhythm you can follow, for example tiptapping with your feet. Complex, almost unpredictable sequence of down and upbeats are possible, but they are rather uncommon in classical and pop music. Even though not so regular as the classical “rhythms”, a high level structure of the accents must emerge; otherwise I think the piece could seem “chaotic”.

On the other hand, if you play notes without accents, you won't feel the pulse, the rhythm; the piece will seem flat and boring, or mechanical and static.

The “unit” of the pattern of the accents is (usually) the measure, also called bar. The bar embraces all the beats that show a specific pattern of accents (an alternation of down- and upbeats). This unit is repeated over and over again, and length of a musical score can be measured in terms of how many bars it contains. Often bars are also numbered, so that you (or maybe a conductor or a musician) can refer to them easily.

The time signature says how many beats make a whole bar, and it says that by specifying the number of notes of a given duration, so that these notes complete the bar. For instance: a bar is made of four crotchet, i.e. four quarter notes. This is written as 4/4 (4 × 1/4).

When the bar is completed, we draw a vertical single line (other “style” of vertical lines have special meaning, e.g. to mark the end of the score — we'll see them in future lessons, when and if I'll talk about composition. To talk about harmony we don't need many things, but knowing a bit of musical notation is anyway useful).

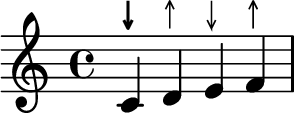

Four quarter notes make a whole note, as we know; so that the whole note occupies the whole 4/4 bar. The 4/4 time signature is a “binary” time signature and it is very common, so that there's a special symbol for it, a sort of C.

This metre is made of two pairs of beats: downbeat + upbeat and downbeat + upbeat (this is why it's a quadruple time), where the second downbeat is less stressed than the first downbeat (a full bar starts always with a downbeat).

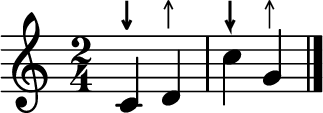

Another very common time is 2/4, a duple time, typical of marches; the downbeat+upbeat pattern is simply this one:

Here I've put two bars and ended the piece with the end-of-the-score bar, just to show it.

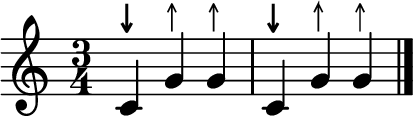

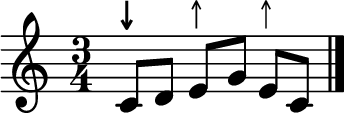

Another very common time signature is 3/4, typical of walzer, for instance. (But also other triple metres works for waltz.)

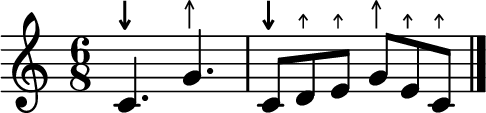

Another duple time is 6/8, which is a compound duple time: we have six eighth notes' beats grouped by three.

In the previous lesson I wrote:

Beamed notes are grouped notes, and this grouping has an informative meaning.

Now you see that the beaming highlights the metric structure of the measure (bar). Compare it with 3/4 when writing eighth notes:

Wikipedia has nice videos showing in practice how these compound metres work (see Time signature).

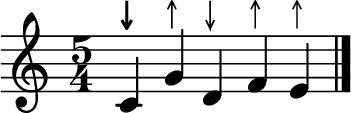

Other time signatures which aren't duple or triple (simple or compound) are possible. For instance 5/4, which can be thought as made of 3/4 followed by 2/4, or 2/4 followed by 3/4…:

You can write it more explicitly, like this:

In the latter way you can omit the + sign.

Of course you can change time signature in the middle of your piece:

If your piece is like this, with a repeating pattern which a reader can easily and unambiguously recognize, then likely you will avoid to write the time signatures over and over again: the total duration of the notes inside the bar will speak for itself. I've told this to stress that we are dealing with a convention which, as far as it can be understood and interpreted, is rather flexible.

Rest your ears!

You will always write complete bars… (Almost)…

A complete bar is a bar where the sum of all the durations of the notes make what a time signature says. You can't put more notes if they don't fit the metre!

For each notes' duration, it exists a rest; a rest is “silence” lasting for e.g. a quarter note, or a whole note. Notation is easy (beware the bar lines!):

As you can see, rests for notes shorter than a quarter note have “flags” too, one for each flag of the note. Rests can be dotted and double dotted (not shown in the above picture) too. The name of each rest, if you need to call it, is the same as the one of the note with the same duration.

Upbeat first, please

I've just said that you will always write a complete bar. This is true (though your way of handwriting music could skip to put rests e.g. to fill a bar, except when you want to start your musical piece with an upbeat. In this case you'll write just the upbeat you need: the first bar isn't complete, it is as if there were (invisible) rests at the beginning. These rests aren't only invisible in the sense that you don't write them down: they aren't played too. (Playing a rest means to stay silent for its duration!)

Notice that the first note played is an upbeat, then followed by a downbeat (the first note of the next bar). Notice also that the last bar I've written isn't complete (1/4 + 1/2 = 3/4) — but if you imagine to “fold” the score so that the last upbeat of the last bar overlap the first upbeat… you've a piece that you could play forever ad libitum… a never ending circular piece.

If you play the piece, you should recognize it… It's the incipit of the famed Top Gun Anthem. Indeed it seems that the original (by Faltermeyer) doesn't start with an upbeat: listen carefully to the rhythm (follow the drums) and don't let you be brought off-road by the fact that the first note (its pitch) is reached “sliding” from a lower pitch which begins a little bit before the beat. Later drums stress the beat more clearly. At least it seems so to me; anyway, it doesn't matter: I've just adapted it in order to show an example of anacrusis.

Scales, to begin with

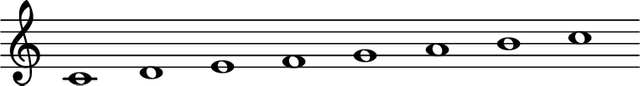

In this second part of the current lesson I'll introduce the idea of scales. We've already met them someway. A scale is just a sequence of notes, one higher (ascending scale) or lower (descending scale) of the previous one, and all contained in an octave.

Duration of the notes and time signature when we show these concepts (and also in future lessons when I will talk about harmony) aren't important at all, so keep your focus at the pitch.

The scale begins with a note (in this example it's C) and ends with another note, in this case with B (then the next octave begins, of course with the first note of the scale). The first note is an important one, and it can be called root note, key note or tonic.

Those are all the natural notes (the white keys of a piano), and this scale (made of seven notes) is a “C scale”, because it starts with a C (its root note). More exactly it is a C-major scale.

Major? What?

We've seen that an octave “contains” 12 notes, according to 12-tones equal temperament; seven of these notes are called natural and have a name, while the remaining five are obtained altering the pitch of the natural notes (e.g. C♯, B♭, …). We've also seen that between these natural notes there's a tone (= two semitones), except between E-F and B-C.

The way tones and semitones are distributed makes a pattern of intervals, which is not the only one possible, of course. The pattern also fixes the number of notes in the scale. When we have seven notes in a scale, we have a heptatonic scale — hepta is seven in Greek. All the scale made of seven pitches are, by definition, heptatonic scales.

A heptatonic scale with intervals of five tones (like between these: C-D, D-E, F-G, G-A, A-B) and two semitones (like between these: E-F, B-C) put so that the semitones are separated by two or three tones, is called a diatonic scale. The “white keys” of the piano can play all the possible diatonic scales, i.e. all the possible patterns of intervals with the property described above.

This isn't by chance: this fact has roots in the history of western music; it's also related to why we have only seven “natural” notes (with their own names) when we at last decided that an octave is divided in 12 tones… But I won't talk about this; I want just to remember the fact that the music how-we-know-it, how-we-write-it, and how-we-theorize-it (beyond the physical properties of the sound), is mostly a “tradition”, with rational, yet almost totally arbitrary, choices “fixed” by history and practical considerations.

You could hear expressions like “diatonic melody” to say that the melody can be played using the white keys of a piano only, or “diatonic instrument” to say that it's an instrument which can play only the seven natural notes (indeed they don't need to corresponds to the white keys of the piano, they need only to provide the expected pattern of intervals — then we can talk about the tuning of such a diatonic instrument, think about diatonic harmonicas).

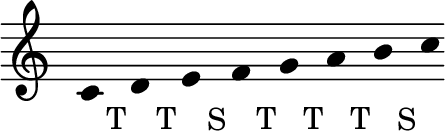

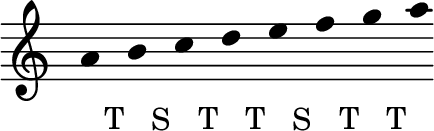

The pattern of tones (T) and semitones (S) we have when we start the scale from C, forms the so called major scale. Hence, since we started from C, we call it a C major scale.

So, the pattern TTSTTTS is a trait of every major scale. If you start from D, the pattern will be TSTTTST (like if you've moved the first tone from the front of the pattern to its tail). This is the so called Dorian mode, if we want to describe it in this way; but we can continue to call it simply a major scale.

Not all “modes” we obtain starting from a note different from C are widely used — music which use Gregorian modes may sound rather odd or ancient, or on the contrary, very “modern” but “odd” anyway to whoever isn't accustomed to it, and we usually aren't, because pop music (but also tons of well-known classical musical pieces) is not based on them.

If we start from A, we obtain another pattern widely used in music, and the scale is a A natural minor scale (ascending):

We can replicate these patterns (major TTSTTTS, and natural minor TSTTSTT) starting from every note, but of course we can't do it only with natural notes.

If you move all notes of a scale upward (or downward) by the same amount of semitones, you've transposed them. This transposition by a specific interval preserves the relative intervals between notes, hence also our patterns; you can always apply it, for example if a melody is too low to sing for your voice, you can transpose it upward, until you can sing it easily.

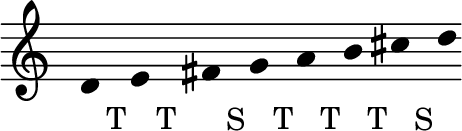

Let us suppose I want a D major scale. The distance between C and D is 2 semitones, so this is the quantity by which I must raise the notes. If you raise C by a tone you obtain a D (in fact the interval C-D is a tone), if you raise D by a tone you obtain E, if you raise E by a tone you obtain… F♯. In fact there's a semitone between E and F, so you must go a semitone up from F, that is, F♯, as we've learnt. And so on. The D major scale will be this:

The notes F and C are altered, they are sort of “pulled up” to increase the interval from the previous notes; since the next note (G and D respectively) stays fixed, the interval between those diminish to a semitone. It is always so: if you increase the “distance” between C and D raising D by a semitone, then the “distance” between D and E decreases. This is how you “move” the intervals between the notes, therefore changing the pattern.

What if I want a B natural minor scale? Let's transpose the A natural minor scale up by two semitones.

If you think about it, you shouldn't be too much surprised of the fact that the altered notes are again F and C. If you consider these seven notes (D, E, F♯, G, A, B, C♯) you still can do all the scales you do with the natural ones, except that the former plays a tone above the latter. If you detune your instrument so that it plays all notes 2 semitones higher, you'll obtain a D when you think you are playing a C! Like if your tuning fork gave 493.8833 Hz in stead of 440 Hz!

There exist transposing instruments for which you'll write the notes at a pitch, but they will sound at another pitch — reasons for this are given in the Wikipedia page linked above; from a composer point of view, it means that he must write notes transposed in the “opposite direction” the instrument is “tuned”; e.g. a B♭ clarinet is a clarinet that plays a B♭ when you write a C, therefore you must write a D if you want to ear an actual C! A reason to transpose by a full octave is when the range of the instrument is always outside the treble staff (up) or the bass staff (down). For instance the double bass is notated on a bass staff, but it really plays an octave lower.

Back on scales.

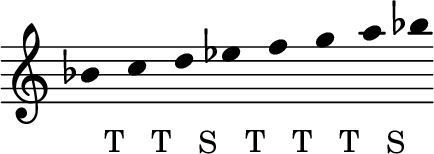

Now you can build you major and natural minor scales transposing C major scale and A natural minor scale. Let's do another try with the B♭ major scale. In this case you must lower the C by a semitone, so you will use flats instead of sharps.

Also in this case we have two altered notes, namely B♭, which is our key note (the first note of the scale), and E♭. We already had the B natural minor scale, so we need to lower it just of a semitone to obtain also the B♭ natural minor scale. Let's do it.

Wow, lots of flats!

No matter how many flats or sharps there are, once you have set them up, you have 7 different pitches and you can use them to build a major scale and a natural minor scale. In fact, the very same seven natural notes are used both for the C major scale and for the A natural minor scale: same notes, different root note, hence different pattern of intervals, and so different “mode”.

The same must happen for the other example: the B♭ natural minor scale has all the notes you need to build also the D♭ major scale; the B♭ major scale has all the notes you need to build also the G natural minor scale; the notes of the B natural minor scale are the same needed for the D major scale…

Key signature

Let's see another notational device.

We've seen that the B♭ natural minor scale has five notes with an accidental (namely the flat). In a previous lesson I've explained that the natural sign (♮) is used to cancel a preceding accidental (♯ or ♭) for the same note (at the very same pitch), because it holds the convention that you need to write an accidental only once in a bar. You need to write it again in the new bar, anyway.

Because you're writing your piece using only the notes of the B♭ natural minor scale, you would like to specify this and then to avoid to write all those flats. You can do it specifying the flats on the right of the clef, like this:

This is the key signature. It is tidier and saves you from writing flats over and over again, which is an error prone procedure, especially for long pieces.

If you need to write, say, an A in stead of a A♭, you use the natural sign, and after that, if in the same bar you need the A♭ again, you must write the flat explicitly again, otherwise the natural sign will be still in effect:

The second note in the second bar is an A♭, because the bar made the natural sign in the first bar to be forgotten. This is why we need to write it again for the third note in the second bar.

The key signature doesn't specify if our piece will use the tonality attached, so to speak, to the B♭ natural minor scale or rather the one attached to the D♭ major scale. This we'll be determined by the piece itself. The root note is some kind of magnet, and it's also called tonic, as said before. In these example, clearly I've used the the B♭ minor tonality, in fact I've started and ended the short melody with the root note; even if in the second example there are notes not belonging to the B♭ natural minor scale (the A), the intended tonality is still that one. These things will be someway explained in future lessons.

Key signatures can't be arbitrary; you can't write e.g. a single flat on the E “space”. If you play with transpositions as explained in the previous section, you'll see that flats (or sharps) increase or decrease in a precise way, so that it is enough to say how many flats (or sharps) there are in a key signature to specify it: you don't need to say on which note you need to put each flat.

A scale with a E♭ in stead of a E would have the pattern TSTTTTS, which breaks our constraint of having the two semitones separated by two or three tones. When you concatenate the pattern, TSTTTTS TSTTTTS …, you see that in a single octave the two semitones are far away, but among two octaves they are 1 tone apart. This pattern isn't found in diatonic scales, anyway.

You can patiently make all the major and natural minor scales by transposing the C major scale or the A natural minor scale, as shown before.

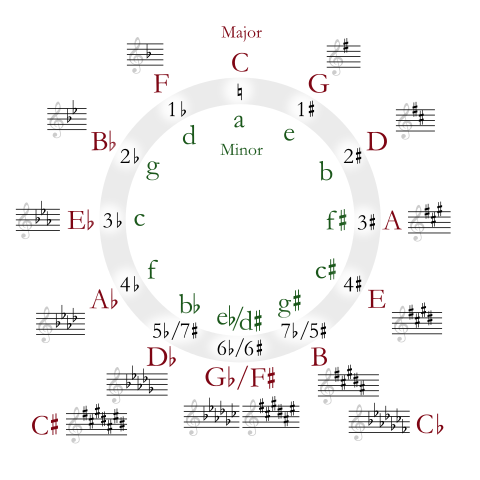

But there's an useful representation called the circle of fifths which helps to select the right key signature for the major or minor scales you want to write.

(Image by Just plain Bill - CC BY-SA 3.0, Link)

The term “fifth” refers to an interval. Let's begin with C, and go up of one “step” (note), counting until 5: C (1), D (2), E (3), F (4), G (5). The fifth of C is G. Each time you go up of a fifth, you count one sharp added and say that from the fifth you've found (G) it begins a major scale. Let's continue from G (1 sharp): G (1), A (2), B (3), C (4), D (5). D is the fifth of G: the D major scale has 2 sharps. And so on. You must beware that you're adding sharps, so that at a certain point you'll find a fifth which is not a natural note anymore.

You can use the same procedure starting from A: A (1), B (2), C (3), D (4), E (5). One sharp, again, but this time we've starting from the A, from which we build the natural minor scale, so that one sharp in the key means we can build a natural minor scale from E; but also, as seen above, a major scale from G. Let's go up of another fifth: E (1), F (2) — which is indeed a F♯ —, G (3), A (4), B (5). With two sharps, you have a major scale from D, or natural minor scale from B.

Instead of going up of a fifth, we could go down; in this case we are adding flats, not sharps. Let's start with C: C (1), B (2), A (3), G (4), F (5). A single flat in the key signature means that we can build a major scale starting from the key note F. Let's start from A: A (1), G (2), F (3), E (4), D (5). So with a flat we can build a natural minor scale from D. And so on.

To know where sharps and flats go, you can build the scale, an interval at time. E.g. consider the G major scale, which has 1 sharp as key signature. Since it's a major scale we must build the pattern TTSTTTS. So the next note after G must be A, (between G and A there's a whole tone). After A, it comes B. Still fine, because there's a whole tone between A and B, too. Now we need a semitone. And it happens that there's one in between B and the note after B, which is C. So we don't need the sharp yet. You go on this way until you'll find that between E and F there's a semitone, as we know, but we need a tone. So we put our sharp on the F.

Ok, now we know more or less how to “build” our key signatures.

Many musical pieces keep the same key signature, but if you need to change it, of course you can. When you add flats or sharps, you just write the signature as usual. When you remove flats or sharps, natural signs can be used to “cancel” the flats or sharps we don't need anymore.

Index of the lessons so far (the current one excluded)

- Lesson 1: basic knowledge about sound.

- Lesson 2: dissonance, consonance, tuning, 12-tones equal temperament, notes' names and notes on a staff, treble and bass clefs.

- Lesson 3: semitones, duration, beaming, tempo.

- Lesson 4 (this lesson): time signature, downbeat, upbeat, rests, ascending major and natural minor diatonic scales, key signature, circle of fifths.

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Super post! :)

Thank you!

idea simpatica! (io suono la chitarra classica da circa 40 anni ^^)

Grazie! Spero che sia anche (un po') utile :-)