The Early Schools of Indian Buddhism Series

How the Theravada School Dealt With Doctrinal Points From Other Schools

The Katha-vatthu — Chapter 5

In Part 8 of this series, we looked at the schools that ‘participated’ and ‘did not participate’ in the Third Council of Buddhism, according to the Kathavatthu, the text that deals with the ‘points of controversy’ from schools other than Theravada. As was mentioned in Part 8, the Kathavatthu is classified as a canonical text in the Theravada tradition, as being part of the Abhidhamma Pitaka, although the text has been expanded up until the second century AD, as evidenced by the ‘late’ schools that are mentioned in the text. Likely, the text started out small and was expanded as more controversial viewpoints from other schools were encountered and dealt with as such.

The Kathavatthu includes a total of 217 points of controversy, divided into twenty-three chapters, where each point is associated with one or more schools, although a few are not assigned to any particular school at all. Due to a large number of doctrinal points covered, I have divided this Part 12 of the series into seven chapters, with each chapter covering one or more of the schools and their doctrinal points of ‘controversy.’

The total number of points of ‘controversy’ for each school covered in this chapter:

- Aparaseliyas: 5

- Rajagirikas: 10

- Siddhatthikas: 8

- Gokulikas: 1

- Bhadrayanikas: 1

- Mahimsasakas: 9

Overview of the chapters that cover the various schools:

- Chapter 1 — Vajjiputtakas, Sammitiyas, Sabbatthivadins

- Chapter 2 — Kassapikas, Mahasanghikas

- Chapter 4 — Pubbaseliyas

- Chapter 5 — Aparaseliyas, Rajagirikas, Siddhatthikas, Gokulikas, Bhadrayanikas, Mahimsasakas

- Chapter 6 — Uttarapathakas

- Chapter 7 — Hetuvadins, Vetulyakas, Not assigned to any school, No points assigned

In this post we’ll be looking at the schools for Chapter 5 — Aparaseliyas, Rajagirikas, Siddhatthikas, Gokulikas, Bhadrayanikas, Mahimsasakas

The given name for the schools in this post follow the Theravada name designation as mentioned in the Kathavatthu text, followed by the Sarvastivada name designation by Vasumitra in his Samaya-bhedoparacanacakra text. The Kathavatthu is divided into twenty-three chapters. Each point of controversy’s headline listed here starts out with the Kathavatthu reference of book (in Roman numerals) and point, i.e., IX. 4 means book nine, point four.

Section 1 — Aparaseliyas (Aparasaila) (5 points of controversy)

This is the school who geographically identify themselves as those who dwell as western highlanders in the Andhra region. Their school was at Dhanakataka, in the Andhaka country, somewhere near Amaravati on the South-East coast of India. According to one tradition, they were connected with the Caityasaila.

Point 1 — II. 1. Of Conveyance by Another

That an Arahant has impure discharge.

This was asked concerning a notion entertained by the Pubbaseliyas and Aparaseliyas. These had noted seminal discharge among those who professed Arahantship in the belief that they had won that which was not won, or who professed Arahantship, yet were overconfident, and deceitful. Also, they wrongly attributed to devas of the Mara group the conveyance, to such, of an impure discharge. This leads to the second question since even a pure discharge is caused by passion.

Point 2 — XIII. 4. Of one whose Salvation is Morally Certain (niyata)

That one who is morally certain of salvation has entered the Path of Assurance (niyama).

Niyama (Assurance) is of two kinds, according to as it is in the wrong or the right direction. The former is conduct that finds retribution without delay (anantariyakamma), the latter is the Ariyan Path. Moreover, there is no other. All other mental phenomena happening in the three planes of being are not of the invariably fixed order, and one who enjoys them is himself ‘not assured.’ Buddhas, by the force of their foresight, used to prophesy: ‘Such a one will in future attain to Bodhi’ (Buddhahood). This person is a Bodhisat, who may be called Assured (Niyata), because of the cumulative growth of merit. Now the Pubbaseliyas and Aparaseliyas, taking the term ‘Assured’ without distinction as to direction, assumed that a Bodhisat was becoming fitted to penetrate the Truths in his last birth, and therefore held that he was already ‘Assured.’

Point 3 — XIV. 2. Of the (pre-natal) Development of Sense-Organs

Point—That the sense-mechanism starts all at once as life in the womb.

Our doctrine teaches that at a human rebirth the development of the embryo’s sense-mechanism or mind is not congenital, as in the case of angelic (Opapatika) rebirth. In the human embryo, at the moment of conception, the coordinating organ (manayatana) and the organ of touch alone among the sense-organs, are congenital. The remaining four organs (eye and ear mechanism, smell and taste mechanism) take seventy-seven days to come to birth, and this is partly through that karma which brought about conception, partly through some other karma. (technically called janaka-karma and upatthambaka-karma; reproductive and maintaining karmas.) However, some, like the Pubbaseliyas and the Aparaseliyas, believe that the sixfold sense-organism takes birth at the moment of conception, by the taking effect of one karma only, as though a complete tree were already potentially contained in the bud.

Point 4 — XVI. 4. Of Attending to Everything at Once

That one can attend to everything simultaneously.

Attention has two aspects, according to as we consider the method or the object of attention. To infer from the observed transience of one or more phenomena that ‘all things are impermanent’ is attention as (inductive) method. However, in attending to past things, we cannot attend to future things. We attend to a particular thing in one of the time-relations. This is attention by way of the object of consciousness. Moreover, when we attend to present things, we are not able at the present moment to attend to the consciousness by which they arise. Nevertheless some, like the Pubbaseliyas and Aparaseliyas, because of the Word, ‘All things are impermanent,’ hold that in generalizing we can attend to all things at once. Also, because they hold that in so doing we must also attend to the consciousness by which we attend, the argument takes the line as stated.

Point 5 — XXII. 8. Of Momentary Duration

That all things are momentary conscious units.

Some—for instance, the Pubbaseliyas and the Aparaseliyas—hold that, since all conditioned things are impermanent, therefore they endure but one conscious moment. Given universal impermanence—one thing ceases quickly, another after an interval—what, they ask, is here the law? The Theravadin shows it is but arbitrary to say that because things are not immutable, therefore they all last but one mental moment.

Section 2 — Rajagirikas (10 points of controversy)

This is one of the four Andhakas schools. These are the points of controversy that they uniquely adhered to:

Point 1 — VII. 1. Of the Classification of Things

That things cannot be grouped together by means of abstract ideas.

It is a belief held, for instance, by the Rajagirikas and the Siddhatthikas, that the orthodox classification of particular, material qualities under one generic concept of ‘matter,’ etc., is worthless, for this reason, that you cannot group things by means of ideas, as you can rope together bullocks, and so on. The argument seeks to point out a different meaning in the notion of grouping. Physical grouping is, of course, the bringing together of many individuals. However, things may be grouped mentally, i.e., included under a concept of totality involved in counting, or a general concept by generalizing.

Point 2 — VII. 2. Of Mental States as Mutually Connected

That mental states are not connected with other mental states.

This again is a view of some, for instance, the Rajagirikas and Siddhatthikas, namely, that the orthodox phrase ‘associated with knowledge’ is meaningless, because feeling or other mental states do not pervade each other (anupavittha) as oil pervades sesame-seeds. The argument is to show ‘connected’ to another aspect.

Point 3 — VII. 3. Of Mental Properties

That mental properties do not exist.

Once more, some, like the Rajagirikas and Siddhatthikas, hold that we can no more get ‘mental properties’ (cetasika) from mind (citta), than we can get ‘contact properties’ from contact, so that there is no such thing as a property, or concomitant, of mind. The Theravadin contends that there would be nothing wrong if custom permitted us to say ‘contact dependent’ for what depends on contact, just as it is customary usage to call ‘mental’ for that which depends on the mind (citta-nissitako).

Point 4 — VII. 4. Of Giving and the Gift

That dana (giving) is (not the gift but) the mental state.

Dana is of three kinds: (note 1) the will to surrender something, abstinence, and the gift. In the sentence—Faith, modesty, and meritorious giving,—we have the will to surrender something when the opportunity occurs. In the phrase ‘he gives security,’ abstinence, when the opportunity occurs, is meant. In the phrase ‘he gives food and drink in charity,’ a thing to be given on a given occasion is meant. The first is dana, in the active sense, as that which surrenders, or, in the instrumental sense, as that by which something is given. Abstinence is giving in the sense of severing from, cutting off. When it is practiced, one severs, cuts off the immoral will which we consider to be a fearful and dangerous state. Also, this is a ‘giving.’ Finally, dana implies that an offering is given. This triple distinction is in reality reduced to two: mental and material.

But the view held, for instance, by the Rajagirikas and Siddhatthikas, recognizes the former (mental) only. Moreover, the object of the discourse is to clear up the confusion (lege sankara-bhavam) between the meanings of this dual distinction.

Point 5 — VII. 5. Of Utility

That merit increases with utility.

Some, like the Rajagirikas, Siddhatthikas, and Sammitiyas, from thoughtlessly interpreting such Suttas as ‘merit day and night is always growing,’ and ‘the robe, monks, which a monk is enjoying the use of... .,’ hold that there is such a thing as merit achieved by utility.

Point 6 — VII. 6. Of the Effects of Gifts given in this Life

That what is given here sustains elsewhere.

Some hold it—for instance, the Rajagirikas and Siddhatthikas—that because of the text: ‘By what is given here below. They share who, dead, among Petas go,’ gifts of robes, etc., cause life to be sustained there.

Point 7 — XIII. 1. Of Age-long Penalty

That one doomed to age-long retribution must endure it for a whole kappa (aeons).

This concerns those who, like the Rajagirikas, hold the notion that the phrase, ‘one who breaks up the concord of the Order is tormented in purgatory for a kappa,’ (Itivuttaka 18) means that a schismatic is so ‘tormented for an entire kappa.’ (for aeons)

Point 8 — XV. 9. Of Trance (part 3) (jhana)

That a person may die while in a state of trance.

The Rajagirikas and others hold that since life is so uncertain, even one who has attained in Jhana to trance may die, no less than anyone else. The argument shows that there is a time for dying and for not dying.

Point 9 — XVII. 2. Of Arahants and Untimely Death

That an Arahant cannot have an untimely death.

From carelessly grasping the Sutta cited below, some—to wit, the Rajagirikas and Siddhatthikas—hold that since an Arahant is to experience the results of all his karma before he can complete existence, therefore he cannot die out of due time.

Point 10 — XVII. 3. Of Everything as due to Karma

That all this is from karma.

Because of the Sutta cited below, the Rajagirikas and Siddhatthikas hold that all this cycle of karma, corruptions, and results are from karma.

Section 3 — Siddhatthikas (8 points of controversy)

This is one of the four Andhakas schools. These are the points of controversy that they uniquely adhered to:

Point 1 to 6: Same as point 1 to 6 of the Rajagirikas.

Point 7 — XVII. 2. Of Arahants and Untimely Death

That an Arahant cannot have an untimely death.

From carelessly grasping the Sutta cited below, some—to wit, the Rajagirikas and Siddhatthikas—hold that since an Arahant is to experience the results of all his karma before he can complete existence, therefore he cannot die out of due time.

Point 8 — XVII. 3. Of Everything as due to Karma

That all this is from karma.

Because of the Sutta cited below, the Rajagirikas and Siddhatthikas hold that all this cycle of karma, corruptions, and results are from karma.

Section 4 — Gokulikas (Kaukkutika = Lokottaravada) (1 point of controversy)

This school considered all aggregates, no more than a heap of embers (kukkula), from which the flames died out as from an inferno of ashes. They based their view on the Buddha's declaration made in the Adittapariyaya Sutta (“All is on fire, monks”).

Point 1 — II. 8. Of the World as only a Cinder-heap

That all conditioned things are absolutely (anodhikatva: not having made a limit, without distinction) cinder-heaps.

The opinion of the Gokulikas, from grasping thoughtlessly the teaching of such Suttas as ‘All is on fire, monks!’ (Vinaya i.134) ‘All conditioned things (involve) suffering,’ (DN ii.175) is that all conditioned things are without qualification no better than a welter of embers whence the flames have died out, like an inferno of ashes. To correct this by indicating various forms of happiness, the Theravadin puts the question.

Section 5 — Bhadrayanikas (Bhadrayaniya) (1 point of controversy)

This school identifies themselves as the vehicle of the sages. The name of this school means ‘Used to being auspicious,’ this is far from being a modest Buddhist school name at all! The Katha-vatthu translation calls it the ‘lucky vehicle’.

Point 1 — II. 9. Of a Specified Progress in Penetration

That penetration is acquired in segmentary order.

By thoughtlessly considering such Suttas as—‘Little by little, one by one, as pass, The moments, gradually let the wise,’ etc., (Sutta Nipata verse 962), the Andhakas, Sabbatthivadins, Sammitiyas, and Bhadrayanikas have acquired the opinion that, in realizing the Four Paths, the corruptions were put away by so many slices as each of the Four Truths was intuited.

Section 6 — Mahimsasakas (Mahisasaka) (9 points of controversy)

This school is identified by the founder being a brahmin who governs the land.

Point 1 — II. 11. Of Cessation

That there are two cessations (of suffering).

The Mahimsasakas and the Andhakas believe that the Third Truth (as to the Cessation of suffering), though constructed as one, relates to two cessations, according to as sorrow ceases through reasoned or unreasoned reflections about things.

Point 2 — VI. 2. Of Causal Genesis

That the causal elements in the law of causal genesis are unconditioned.

Because of the text in the chapter on causation— ‘whether Tathagatas arise or do not arise, this elemental datum which remains fixed,’ etc., some, as the Pubbaseliyas and the Mahimsasakas, have arrived at the view here affirmed.

Point 3 — VI. 6. Of Space

That space is unconditioned.

Space is of three modes: as confined or delimited, as abstracted from the object, as empty or inane. Of these the first is conditioned; the other two are merely abstract ideas. However, some, like the Uttarapathakas and Mahimsasakas, hold that the two latter modes also, since (being mental fictions) they are not conditioned, must, therefore, be unconditioned.

Point 4 — VIII. 9. Of Matter as ethically Good or Bad

That physical actions (involved in bodily and vocal intimations) proceeding from good or bad thoughts amount to a moral act of karma.

Some (as, for instance, the Mahimsasakas and the Sammitiyas) hold that acts of body and voice being, as they are, just material qualities, reckoned as bodily and vocal intimation are morally right if proceeding from what is right, and morally wrong if proceeding from what is evil. However, it runs the counter-argument, they are to be considered as positively moral, and not amoral—as we are taught—then all the characteristics of the morally good or bad must apply to them, as well as material characteristics.

Point 5 — X. 2. Of the Path and Bodily Form

That the physical frame of one who is practicing the Eight-fold Path is included in that Path.

Those who, like the Mahimsasakas, Sammitiyas, and Mahasanghikas, hold that the three factors of the Path:—supremely right speech, action, and livelihood—are material, are confronted with the contradiction that, since the factors of the Path are subjective, they imply mental attributes lacking in matter.

Point 6 — XVI. 7. Of Matter as Morally Good or Bad

That material qualities are (i.) good or moral, (ii.) bad or immoral.

The Mahimsasakas and Sammitiyas, relying on the Word—acts of body and speech are good or bad’—and that among such acts we reckon intimations of our thought by gesture and language, hold that the physical motions engaged therein are (morally) good or bad.

Point 7 — XVIII. 6. Of the Transitions from One Jhana to Another

That we pass from one Jhana to another (immediately).

Some, like the Mahimsasakas and certain of the Andhakas, hold that the formula of the Four Jhanas (in the teachings) warrants us in concluding that progress from one Jhana-stage to another is immediate without any accessory procedure.

Point 8 — XIX. 8. Of the Moral Controlling Powers (five faculties or factors of ‘moral sense’: indriya)

That the five moral controlling powers—faith, effort, mindfulness, concentration, understanding—are not valid as ‘controlling powers’ in worldly matters.

This is an opinion held by some, like the Hetuvadins and Mahimsasakas.

Point 9 — XX. 5. Of the Ariyan Path

That the Path is five-fold (only).

Some, such as the Mahimsasakas, hold that in general terms the (Ariyan) Path is only fivefold. They infer this both from the Sutta, ‘One who has previously been quite pure,’ etc., and also because the three eliminated factors—speech, action, and livelihood—are not states of consciousness like the other five.

In the next article, we will discuss how the Theravada school dealt with the doctrinal points from other Buddhist schools, as recorded in their Katha-vatthu text — Chapter 6 — Uttarapathakas.

- Introduction to the history of Buddhist Councils and Schools-Part 1

- The Buddhist Councils — Who, when, where, and why?Part 2

- The Buddhist Councils — Who, when, where, and why?Part 3

- The History Of ‘Northern Buddhists’ of Sarvastivada - Part 4

- The History Of ‘Northern Buddhists’ of Sarvastivada - Part 5

- Buddhist schools at the time of the First ‘Maha-Kasyapa’ Council at Rajagaha. - Part 6

- Buddhist schools at the time of the First ‘Maha-Kasyapa’ Council at Rajagaha. - Part 7

- Buddhist schools at the time of the Third ‘Moggaliputta Tissa’ ‘Asoka’ Council - Part 8

- Buddhist schools at the time of the Fourth ‘Vasumitra’ ‘Kanishka’ Council at Jalandhar. - Part 9

- Buddhist schools in the 5th Century A.D. according to the Chinese pilgrim Fa-hsien - Part 10

- Buddhist schools in the 7th Century A.D. according to the Chinese pilgrim Yuan-Chuang-Part 11

- How the Theravada school dealt with doctrinal points from other schools-Part 12-The Katha-vatthu — Chapter 2

- How the Theravada school dealt with doctrinal points from other schools The Katha-vatthu — Chapter 3 — Part 12 "Continued"

- How the Theravada school dealt with doctrinal points from other schools - The Katha-vatthu — Chapter 3 — Part 12

- How the Theravada school dealt with doctrinal points from other schools - The Katha-vatthu — Chapter 4 — Part 12

- The Ten Stages of the Mahayana Bodhisattva Path-The Two Preliminary Stages-Part 1

- The Ten Stages of the Mahayana Bodhisattva Path-The Two Preliminary Stages-Part 2

- The Ten Stages of the Mahayana Bodhisattva Path-The Two Preliminary Stages-Part 3

- The Ten Stages of the Mahayana Bodhisattva Path-The Two Preliminary Stages-Part 4

- The Ten Stages of the Mahayana Bodhisattva Path-The Two Preliminary Stages-Part 5

- The Ten Stages of the Mahayana Bodhisattva Path-The Two Preliminary Stages-Part 6

- The Ten Stages of the Mahayana Bodhisattva Path-The Two Preliminary Stages-Part 7

- The Ten Stages of the Mahayana Bodhisattva Path-The Two Preliminary Stages-Part 8

- The Ten Stages of the Mahayana Bodhisattva Path-The Two Preliminary Stages-Part 9

- The Ten Stages of the Mahayana Bodhisattva Path-The Two Preliminary Stages-Part 10

- The Ten Stages of the Mahayana Bodhisattva Path-The Two Preliminary Stages-Part 11

- The Deathless In Buddhism

- The "Timeless" Teaching-Being Beyond Temporality

- The Nine Successive Cessations In buddhist Meditations - Part 1

- The Nine Successive Cessations In buddhist Meditations - Part 2

- The Nine Successive Cessations In buddhist Meditations - Part 3

- The Twelve Links Of Dependent Origination

- THINGS to DEVELOP and THINGS to AVOID

- The First Noble Truth

- The Second Noble Truth

- The Third Noble Truth

- The Fourth Noble Truth

- 10 Fold Path Series

- EATING MEAT — WHY THE BUDDHA WAS NOT A VEGETARIAN

I will flag comment spam at 1% strength. If you keep on spamming my post, I will flag you at 100%. I don't care if you have limited English abilities, write a couple of sentences about this article, no copy-paste, please. I will flag: one sentence comments, links to your blog and begging for up-votes and follows. Also, I will flag comments that have nothing to do with my blog's article. I will also check your comment section to see if you have been comment spamming on other blogs.

- Introduction to the history of Buddhist Councils and Schools-Part 1

- The Buddhist Councils — Who, when, where, and why?Part 2

- The Buddhist Councils — Who, when, where, and why?Part 3

- The History Of ‘Northern Buddhists’ of Sarvastivada - Part 4

- The History Of ‘Northern Buddhists’ of Sarvastivada - Part 5

- Buddhist schools at the time of the First ‘Maha-Kasyapa’ Council at Rajagaha. - Part 6

- Buddhist schools at the time of the First ‘Maha-Kasyapa’ Council at Rajagaha. - Part 7

- Buddhist schools at the time of the Third ‘Moggaliputta Tissa’ ‘Asoka’ Council - Part 8

- Buddhist schools at the time of the Fourth ‘Vasumitra’ ‘Kanishka’ Council at Jalandhar. - Part 9

- Buddhist schools in the 5th Century A.D. according to the Chinese pilgrim Fa-hsien - Part 10

- Buddhist schools in the 7th Century A.D. according to the Chinese pilgrim Yuan-Chuang-Part 11

- How the Theravada school dealt with doctrinal points from other schools-Part 12-The Katha-vatthu — Chapter 2

- How the Theravada school dealt with doctrinal points from other schools The Katha-vatthu — Chapter 3 — Part 12 "Continued"

- How the Theravada school dealt with doctrinal points from other schools - The Katha-vatthu — Chapter 3 — Part 12

- The Ten Stages of the Mahayana Bodhisattva Path-The Two Preliminary Stages-Part 1

- The Ten Stages of the Mahayana Bodhisattva Path-The Two Preliminary Stages-Part 2

- The Ten Stages of the Mahayana Bodhisattva Path-The Two Preliminary Stages-Part 3

- The Ten Stages of the Mahayana Bodhisattva Path-The Two Preliminary Stages-Part 4

- The Ten Stages of the Mahayana Bodhisattva Path-The Two Preliminary Stages-Part 5

- The Ten Stages of the Mahayana Bodhisattva Path-The Two Preliminary Stages-Part 6

- The Ten Stages of the Mahayana Bodhisattva Path-The Two Preliminary Stages-Part 7

- The Ten Stages of the Mahayana Bodhisattva Path-The Two Preliminary Stages-Part 8

- The Ten Stages of the Mahayana Bodhisattva Path-The Two Preliminary Stages-Part 9

- The Ten Stages of the Mahayana Bodhisattva Path-The Two Preliminary Stages-Part 10

- The Ten Stages of the Mahayana Bodhisattva Path-The Two Preliminary Stages-Part 11

- The Deathless In Buddhism

- The "Timeless" Teaching-Being Beyond Temporality

- The Nine Successive Cessations In buddhist Meditations - Part 1

- The Nine Successive Cessations In buddhist Meditations - Part 2

- The Nine Successive Cessations In buddhist Meditations - Part 3

- The Twelve Links Of Dependent Origination

- THINGS to DEVELOP and THINGS to AVOID

- The First Noble Truth

- The Second Noble Truth

- The Third Noble Truth

- The Fourth Noble Truth

- 10 Fold Path Series

- EATING MEAT — WHY THE BUDDHA WAS NOT A VEGETARIAN

I will flag comment spam at 1% strength. If you keep on spamming my post, I will flag you at 100%. I don't care if you have limited English abilities, write a couple of sentences about this article, no copy-paste, please. I will flag: one sentence comments, links to your blog and begging for up-votes and follows. Also, I will flag comments that have nothing to do with my blog's article. I will also check your comment section to see if you have been comment spamming on other blogs.

@reddust You've always written a very descriptive article. What is the difference between Mahayana and Theravada when we consider the two articles you wrote earlier? The question comes to mind. To me, the most important difference between Mahayana and Theravada schools of Buddhism is that the Mahayana Buddhism teaches that the entity that reaches Nirvan must also work for the salvation of other beings. In the original Buddhist teaching, Nirvana is an individual thing and it travels from this world that reaches Nirvan.

@turkishcrew from what we could find the Bodhisattva path was created to remove narrow views of the Arahant path, which is salvation only for the Arahant. Although the Arahant's of Buddha's time taught laypeople and monastics the way out of suffering. I think through time the Sangha became isolated from the everyday people and the schools that were to become the Mahayana schools tried to avoid this disconnect from the lay folk, which also increases support for the monastery system and resonated with India's view of enlightenment as well.

Hello @reddust. Regarding Section 2, Point 9. If there is a point of controversy between the Theravada School and the Rajagirikas, should I assume that the Theravada school accepts that an Arahant can die an untimely death even if they do not experience the results of all their karma?

In order to understand this I went to the Wikipedia for the definition of Arahant: It is something like this: "Theravada Buddhism defines arhat (Sanskrit; Pali: arahant) as one who has gained insight into the true nature of existence and has achieved nirvana" Source

My husband is going to look up this view @macusantoniu, both of us remember from our research the Theravada view is that the Arahant is aware of his/her upcoming death, so the Arahant's death is never untimely, Edit: this wrong, the answer is the untimely death of an Arahant from murder would be the karmic result of the murderer.

Interesting where it states that everything is due to Karma. Do Buddhist believe in a multiplier of that Karma in other words if you do bad to someone it will come back at you say tenfold. Thanks so much for sharing tonight @reddust

Karma is complicated, and Buddha warned if you look too closely you may go mad...hahaha it's like a fractal to me, that is my personal opinion. In my opinion without karma Buddhism wouldn't be Buddhism. So learning the basics about karma is very important!

Karma is like a seed, you can have a seed that grows bitter fruit, a seed that grows sweet fruit, and a seed that does not sprout immediately and some sprout in the next season or needs fire and ice to germinate. The body is our old karma, any action no matter is done with good intention or wrong can be neutral, positive, or negative karma. All karma can be let go in this lifetime if one has the right qualities and or takes the teachings from an enlightened person. I can't tell the difference between one mind and another, so I put my trust in the teachings, a teacher's conduct, and my personal experience. I question everything, and my faith must be earned!

This goes into the different kinds of karma, remember karma is the law of nature, cause and effect.

Angulimala Sutta: About Angulimala - translated from the Pali by Thanissaro

I like BhikuThanissaro's translations, they have more spirit/juice when compared to Bhikkhu Bodhi's work, although I love Bhikkhu Bodhi and appreciate all his hard work.

I have heard that on one occasion the Blessed One was staying near Savatthi at Jeta's Grove, Anathapindika's monastery. And at that time in King Pasenadi's realm, there was a bandit named Angulimala: brutal, bloody-handed, devoted to killing & slaying, showing no mercy to living beings. He turned villages into non-villages, towns into non-towns, settled countryside into the unsettled countryside. Having repeatedly killed human beings, he wore a garland (mala) made of fingers (anguli).

One of my favorite stories because if a murder can change his ways and let go of his negative karma anyone of us can too!

What is the difference between the first schools in India and in the schools now?

Depending on historical records 18 to 23 schools are now extinct. 3 traditions are surviving from these schools, Theravada calls itself the original teachings of Buddha, Mahayana also says it has the original teachings of Buddha along with sunyata and bodhisattva views in the Prajnaparamita, which has many schools including Vajrayana which matured and flourished around the lands of Tibet and surrounding countries.

Schools / Lineages

Theravada - Teachings of the Elders

Mahayana - The Great Vehicle

Vajrayana - The Thunderbolt Vehicle

The Chinese Schools

Japanese Buddhist Schools

A Comparative Study of the Schools

Dear @ reddust, Great to see those and know more about it from you thanks for sharing this incredible post.

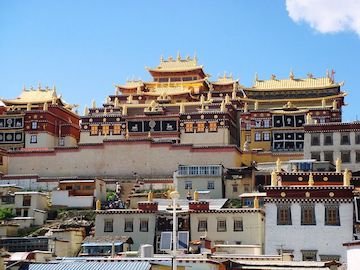

Amazing history of buddhism school...wonderful buildings....such a beautiful pictures....natural beauty.....i appriciate your work...thanks for sharing.

great very complete and interesting history of Buddhism I love, the first image of the tree really is amazing fantastic

Great Post 😆

Great Post !!