Folktales, Race and Class Struggles in Afro-Venezuelan Literature

During my graduate school years I ironically discovered that American universities devoted more resources, space and publications to Venezuelan literature than our own universities. I decided then that it was probably the best chance for me to study my own literature. Thus, I ended up writing my Master’s Essay on “Tío Conejo, Venezuela’s Bre’er Rabbit’s Cousin,” I focused then only on highlighting what I saw as a consistent denial of the African nature of the trickster tales in Venezuelan publications, unlike the American versions popularized by Joel Chandler Harris. I tried to provide background material to establish that African connection, and discussed the ways in which the stories had been appropriated for political purposes.

Source

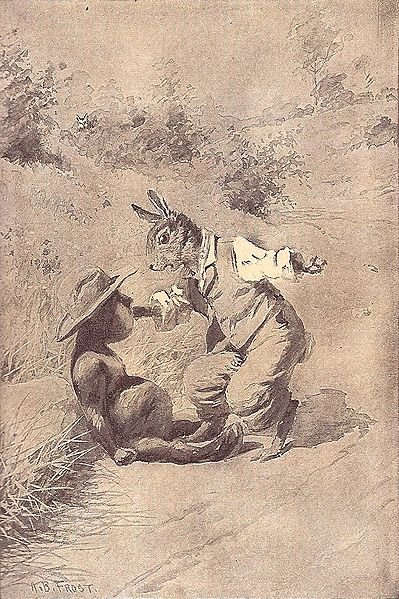

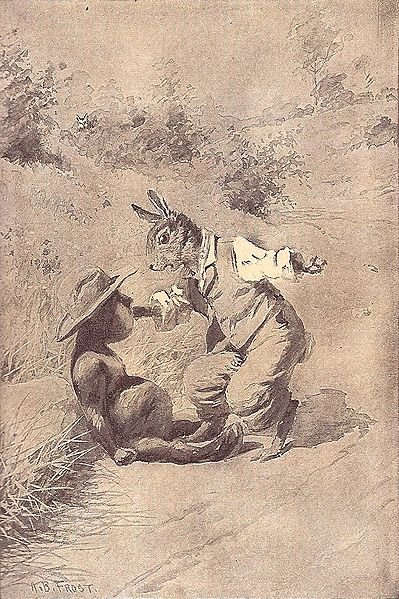

Brer Rabbit (hermano conejo) se queda pegado en el muñeco de brea. Esta ilustración acompaña la versión de 1895 de Joel Chandler Harris Tío Remus: Sus Canciones y Dichos, ilustrado por A.B. Frost

Source

Brer Rabbit (hermano conejo) se queda pegado en el muñeco de brea. Esta ilustración acompaña la versión de 1895 de Joel Chandler Harris Tío Remus: Sus Canciones y Dichos, ilustrado por A.B. Frost

In this post, part of a series devoted to Tío Conejo (Brother Rabbit), I expand on the “Africanness” of these stories, which in Venezuela took a particularly complex route, once authors, such as Arturo Uslar Pietri, Juan Liscano, and Antonio Arráiz, included them in their works. Even though some studies on Venezuelan folklore and literature do refer to the rabbit stories as inherited from Africa, all these works fail to analyze the Africanness (or lack thereof) of the stories in the context of Venezuela’s racist and classist discourse. The racial and social elements of the folktales are absent (whitened?) in children’s publication, but they impact powerfully when used in adult fiction, particularly in Rómulo Gallegos’ Pobre Negro (1937), Juan Pablo Sojo’s Nochebuena Negra (1943), and Ramón Diaz Sanchez’s Cumboto (1948). In all these fictionalized accounts of Venezuelan history and “the black experience” Tío Conejo stories—and their trickster discourse—are an integral part of the racial discourse and the overall tensions between the characters and their environment.

In the context of the history of slavery in Venezuela, slave revolts, independence, abolition of slavery, civil wars, and the integration of the non-white groups to mainstream society, the folk characters (from the supernatural to the bandits) provide interesting facets, not usually discussed, let alone analyzed, which speak of a complex dynamic of appropriation of the folkloric figures (trickster in general and Tío Conejo in particular). If studied in conjunction to mainstream Venezuelan literature, these trickster tales tell us of the characters’ complexities (as much as—and contingent to—the racial mixture and social positioning of those who tell the stories) and the ways in which they can be used to either preserve and propagate culture, or as instruments of social control. Far from a racially/nationally unifying figure, Tío Conejo (when analyzed from its multifaceted “performances”) epitomizes the complexities of the racial and socio-economic disparities Venezuela’s official history has tried to erase.

From Bolivar (“padre de la patria”) to Betancourt (“padre de la democracia”) a homogenizing concept of race in the name of independence movements and democratic revolutions gave birth to erroneous, if not utopian, ideas of democracia racial in Venezuela. Winthrop R. Wright, in Café con Leche: Race, Class, and National Image in Venezuela defines “racial democracy” basic premise: “black achieve great things in Venezuela only as they whiten themselves and their offspring” (115). Whitening is then “an inexact process which involved miscegenation, education, and social advancement” (112). Unlike the USA, where racial tensions have been clearly demarcated by centuries of institutionalized discrimination, segregation, terrorism against minorities, etc., in Latin America, a more subtle racism emerged after the Independence War (1810-1823)—Wright dates this movement a bit later: From the 1860s, with Aristides Rojas and later José Gil Fortoul in the 1890s, the idea that Venezuela constituted a predominantly mestizo nation, was developed. According to these thinkers, “mestizos looked more European than other non-whites” (54). Influenced by Spencerian positivism, “the nation’s elite [advocated] the whitening of the population […] Despite the pride they took in their mixed racial background, many Venezuelans wanted to dilute the café as much as possible with more leche” (2).

This subtle racism, under the motto of “mejorar la raza”, have permeated until present times. This racism has not been any different from the one practiced in the United State, for example, as far as notions of racial superiority is concerned. The main difference is that instead of terrorizing or segregating the non-white groups, Venezuela developed a progressive and “peaceful” program of democracia racial; the ultimate goals being the erasure of those traces of Africanness or Indianness that could make “the race” inferior and/or the progressive marginalization of those “cimarrones” who did not merge and persisted in preserving their ethnicity. By promoting social and biological amalgamation, Venezuela’s white elite were convinced that Venezuela’s raza mestiza would get a step closer to the ideal European model of civilization.

In light of this situation, it has traditionally been argued that Venezuela did not have a Negro literature (produced by black writers). As José Marcial Ramos Guedes put it, “in Venezuela there has not been a trend or school that would give us grounds to see the existence of a literary movement representative of the negritude similar to the one developed by Aime Cesaire (Martiniquan); León G. Damas (Guyanese); Leopold Sédar Senghor (Senegalese), etc.” (14). It is true that Venezuela did not develop (or at least none has been discovered) slave narratives, for instance; neither did Venezuela have an abolitionist movement like the one consolidated in the USA, which allowed the emergence of a Frederick Douglass, William Wells Brown, a Sojourner Truth, or a Harriet Jacobs, as literary and public figures. However, it is worth pointing out that Venezuelan letters have somehow developed a black literature, or at least a literature deeply concerned with racial discourses and the black aesthetics. The problem is that this literature was, for the most part, produced by writers who, under the Venezuelan version of “the one-drop rule,” did not qualify as “Negro writers.”

Winthrop R. Wright explains: “Venezuelan’s visual perception of race differs from that of white North America. The latter have argued that origin determines race and that, by definition, any Negroid features automatically makes an individual black…[Venezuelans] altered the perspective: they considered individuals with a drop of white blood superior to blacks” (Wright 3). Not only have Venezuelans “with a drop of white blood” been considered “superior to blacks” or Indians, but also there has been a conscious attempt to avoid hyphenated identities, such as Native-Venezuelan, African-Venezuelan, etc. (in the last couple of years there have been attempts to institutionalized the term afro-descendientes, to refer to people of black ancestry, but the term has not caught up and most people see as problematic that the government tries to establish affirmative-action-kind of racial differences); thus, unless the writer is unquestionably black or Indian, there will not be any association whatsoever with those particular ethnic groups. “According to historian José Gil Fortoul, writing in the late nineteenth century, the censuses purposefully lacked racial categories because the elites did not want to remind blacks of their painful experience as slaves […]For all intents and purposes, after emancipation took place the blacks simply disappeared from the official records of modern Venezuela” (Wright 4).

Source

Source

I am not sure that the elites were that concerned about soothing blacks’ painful experience. Whenever writers have addressed issues that somehow speak of their ethnicity, their work has been, for the most part, minimized in relation to higher standards of literary art. Julian Padrón said in 1944 that ‘the nation had not produced a major black poet or novelist.’ Most critics agreed that Juan Pablo Sojo, for instance, “failed to win an audience because [he] could not transform his knowledge of folklore into plausible fiction” (Wright 113).

But this colonial snobbism did not affect critics alone. Traditionally, as Wright rightly points out, “successful blacks lost their ties with the less fortunate blacks. They made no attempt to call attention to their race. Nor did they lead any efforts to establish black political or cultural movements” (6). Also, “unlike Argentina, where a black press came into existence during the nineteenth century, [in Venezuela] no newspaper served the interests of blacks” (87). Besides that, the official discourse would indicate that because of miscegenation, Venezuela is a cultura mestiza, therefore it would be preposterous to emphasize the African, Indian, or white nature of a given cultural artifact; instead we should be talking of hybrid cultural manifestations.

But, when we analyze the non-official discourses as represented in folklore and literature, we see that the racist discourse is ubiquitous. In the case of folktales, depending on the intention of the teller, the audience, the context, and the purpose of telling them, africanness, indianness, or whiteness does matter; yet, white discourse has always prevailed and non-white groups have always been misrepresented, at best.

To be continued…

Works Cited or Consulted

Arraiz, Antonio. Tío Tigre y Tío Conejo. Caracas: Monte Ávila Editores, 1980.

Díaz Sánchez, Ramón. Cumboto. Caracas: Editorial Panapo, 1997.

---. Paisaje Historico de la Cultura Venezolana. Buenos Aires: EUDEBA, 1965.

Gallegos, Rómulo. Pobre Negro. Buenos Aires: Espasa-Calpe, 1945.

Ramos Guedez, José Marcial. El Negro en la Novela Venezolana. Caracas: UCV, 1980.

Rivero Oramas, Rafael. El Mundo de Tio Cinejo. Caracas: Ekaré, 1999.

Roberts, John. From Trickster to Badman: The Black Folk Hero in Slavery and Freedom.

Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1989.

Sojo, Juan Pablo. Nochebuena Negra. Caracas: Editorial General Rafael Urdaneta, 1943.

Uslar Pietri, Arturo. La Invencion de America Mestiza. Mexico: FCE, 1996.

Wright, Winthrop R. Café Con Leche. Race, Class, and National Image in Venezuela.

Austin: U. of Texas P., 1993.

Source

Source

Seriously interesting and so glad that I have come into contact with you. You have clearly done a lot of reading/research to put this together.

So well written and interesting to see where it is actually rooted!

!tip

Thank you

You are always welcome!

Hey @hlezama

Clearly a massive amount of research and effort has gone into this. Well done.

It is always interesting to see changes made to something, like a tale, because of time, culture, political and religious influences etc

Thanks for sharing your work.

Gaz

Thanks for stopping by.

Yes, it is fascinating to see how sources merge and evolve within literature and culture. It helps us understand so much more about our culture and our present situation.

Much of the political turmoil we have now was caused by people full of resentment who raised the class flag, dragging with them the poorest sector of our population who may not be identified with a specific race because of how mixed we are, but have the socio-economic factor as a common feature.

Many of the political leaders do not even belong to the working class, but they used their discourse to bring them to their camp.

In the mean time, the political leaders keep enjoying the good life while the poor are simply poorer. They settled for havign leaders who allegedly speak like them. So much for consolation

Excellent read, finding facts within fiction by authors from some time back, hidden treasures.

Artists depicted life in art works, still being looked into, to decipher fact from fiction, interesting connection always back to Africa (must be the center of the world).

It somehow is. Thanks for commenting. Always welcome over here.

So many layers here @hlezama and much of it resonates for the African and South African experience. When I was at university, now more than 30 years ago, I was fortunate to have been able to embark on one of the first courses on African Literature - in then apartheid South Africa. Sadly I had to give it up - it was an additional course but after a really bad car accident, I had to focus on my majors.

However, the layers and the perceptions of "whiteness" and associated superiority all pervade here - post apartheid and in communities that are of mixed race and where fairness of skin still denotes some irrational status.

I am pleased that, some 20 years into democracy some of the South African voices including slave voices are being heard and showcased. Actually, this is making me want to revisit some of the African literature that I've read... Oh, there is so much going through my head that this post has evoked for me. I look forward to your next piece.

Fiona

Thank you very much for sharing your experience with african literature. I am so glad my post provided you a chance to revisit it.

This takes me right back to my literature studies in college. It's suddenly obvious that you are a professor. :-) Keep up the great work!

Thank you very much. Unfortunately, this kind of work never had the the institutional or social support that might have contributed to further it.

It feels good to offer it to good readers.

Do you have hope that it will change in the near future?

If there is a change of government and those in charge deliver what they have promised, part of which involves social and cultural transformations, there might be some aignificant changes. If education is favored over political diatribes, we may see changes in a decade or two.

Change is soooooo slow to happen on a large scale. At least you are doing your part! :-D

That's interesting. Can you tell us somehting about the character of Bro Rabbit?

Greetings, @manoldonchev.

Just in case you have the time, you can check the posts below where I discussed in more details the topic. The short answer to the question, though, is that this is a trickster character, popularized in America by Joel Chandler Harris in his book Uncle Remus, his songs and his sayings (1881). The rabbit of the stories is one of the many impersonations of the African tricksters whose stories, told by the black slaves whenerver in the americas they ended up, adopted different forms and shapes. The trickster (sometimes rabbit, sometimes spider, sometimes human) may trick for no reason or may trick to survive. He also gets tricked. He can be a mythical figure associated with creation myths, or a more modern figure associated with more human affairs.

I found rabbit stories publications in every latin american country (even in Argentina, where black population was incipient). The whole caribbean has rabbit stories, as well as other territories where Africans were brought as slaves.

Part I: https://steemit.com/equipocardumen/@hlezama/tio-conejo-african-roots-and-venezuelan-renditions-part-i

Part II: https://steemit.com/english/@hlezama/tio-conejo-african-roots-and-venezuelan-renditions-part-ii

Part III: https://steemit.com/english/@hlezama/tio-conejo-african-roots-and-venezuelan-versions-part-iii

Part IV: https://steemit.com/history/@hlezama/tio-conejo-african-roots-and-venezuelan-versions-part-iv

Part V: https://steemit.com/english/@hlezama/tio-conejo-folktales-african-roots-and-venezuelan-renditions-part-v

Part VI: https://steemit.com/english/@hlezama/tio-conejo-s-trickster-tales-african-roots-and-venezuelan-

renditions-part-vi

Part VII: https://steemit.com/english/@hlezama/tio-conejo-s-trickster-tales-african-roots-and-venezuelan-renditions-part-vii

I guess the spider associated character Anansi that I read about in modern fiction by Neil Gaiman (although fiction, American Gods is quite on topic , I feel) has a lot in common, then.

Yep. Anansi is the source out if which brother rabbit emerged. Gaiman also wrote Anansi Boys. There the connection is more clearly established

Very impressive - the amount of research and the quality of the writing are contributing factors to making this a very interesting read. There are many faces to racism.

I'm glad you liked it.

There are indeed. All of them can be almeliorated when properly dealt with, understood, and confronted.

Academic research, if made available to the masses, may work as a mirror where those faces may see themselves reflected and reconciled.

Incredible writing, as always, @hlezama. You really covered the topic in depth. I'm amazed. You should consider collecting these writings into a book.

I had not heard of the one-drop rule. It's ridiculous to contemplate the notion that one person of color is superior to another if he/she has any white blood. And for that matter, superiority based on race at all is so incredibly disturbing. It's sad that it has such deep roots, and that these backwater beliefs continue.

Thank you for sharing this enlightening post. Your knowledge and writing skill always amaze me.

Thank you so much, @jayna.

This was indeed my book project. Steemit has helped me give some shape to it. Hopefully, I will be able to publish all this in some form. I posted 7 parts previous to this section (see comment above).

From Charles Chesnutt and his Stories of the Color Line, African Americans have dealt with the issue of passing (blacks who were fair enough to pass as white). There is an African American writer, BarbaraNeely, who, from the perspective of a female detective (Blanche), approaches the nuances of internal racism within american blacks.

The pressure of white-normativity or the benefits associated with whiteness have taken a toll among non-white groups.

Very interesting to hear about racism there and compare it to what we have here in the US. It's very sad, but unfortunately it seems racism exists all over the world still.

Yep. Humans seem to be wired to generate conflict

Wow, this is so enlightening! Unbelievable the way government influences and actually dictates what we read. Add the press to the mix and who know what is truth! Great post @hlezama.

Thank you very much. I appreciate your comment. We have an intellectual obligation regarding these issues. It can enhance our aesthetic experiencing of literature and our social awareness.