Tio Conejo: African Roots and Venezuelan Renditions

(Part II)

Illustration by Alicia Ulloa of one of the stories in Rafael Rivero Oramas's collection

Stories of animal tricksters have been told in Venezuela for centuries. From all the characters that populate the Venezuelan folklore, Tio Conejo was, at some point, the quintessential favorite of children and grown-ups alike. He impersonates the eternal struggle between the weak and the strong; between intelligence and brute force. But, Tio Conejo is not either a Venezuelan or even an American phenomenon. His roots are deeply attached to the African tricksters and the multiple shapes the character adopted in America has a lot to do with the socio-historical circumstances that brought the stories into the continent. The struggles of enslaved Africans to survive physically and culturally are somehow contained in the narrations of the mischievous rabbit whose pranks provided joy and inspiration for the slaves who saw in the tricksters the possibility that their situation could change or at least be bearable if only they acted smart, just like the rabbit in the stories.

Venezuelan modern folklore has appropriated Tio Conejo in multiple ways; from the bad individualistic, yet somehow mystic prankster of conservative folklorist Rafael Rivero Oramas, to the secular, more rational and socially dense character of Antonio Arraiz. This multifaceted aspect of Tio Conejo emphasizes his links with the ancestral African tricksters. He shares “Ananse’s primordial foolery, Legba’s rampant sexuality and mastery of language, Ogo-Yurugu’s rebellion and banishment to the wilderness, and Eshu’s never-ending disturbance of social peace” (Pelton 18).

Source

Source

A section devoted to the origin of the stories is vital because on the one hand Venezuelan scholars have done very little to acknowledge the African heritage of Tio Conejo; on the other hand, the way Rivero and Arraiz have adapted Tio Conejo’s stories allow a revision of two facets of the African trickster: the individualistic and the one concerned with the well being of the community.

The average Venezuelan may know Tio Conejo stories, and yet have no idea where he comes from. The fact that these characters can easily be traced back to the West African trickster tradition has been overlooked. Venezuelans attribute the “creation” of the character to Rivero, Arraiz, or other writers. In the mid and late 20th century, animal tricksters were not only an integral part of Venezuelan children’s literature but were also in tales from other Latin American countries. However, in Venezuela there is reference to “the heroes of the oral tradition” implying their use as vehicles for culture building or as a source for heroic models,

The origin of Tío Tigre and Tío Conejo derive from the Venezuelan folklore of the Llanos [the planes], in which the contradictions and conflicts of our society are described. When the country had traveled the roads of the Independence War and it became necessary to draw the limits of the national identity, the children books turned their attention to the heroes of the oral tradition, populated by personages like Tío Conejo.

Castellano y Literatura by Olga Flores et al. TEDUCA, 1986.

By providing a specific geographical location (the planes) as the original source of the stories, the authors of text books such as this one, make children think about llaneros as the original tellers of tio conejo stories. It would be hard to establish a connection to African slaves from there. Although the rabbit trickster subject appears only in what Venezuelan folklorists have generally referred to as anonymous children’s tales that originated in the Venezuelan rural areas and are part of our popular folklore, the abundant scholarship on the subject evidences that it represents a more global genre occurring in the mythology of almost every so-called primitive society, particularly in those societies where African slavery was the common denominator. In addition to that, I intend to open up a dialogue concerning the process of historico-cultural erasure and socio-political indoctrination that has been taking place in Venezuela for decades and whose political implications have always been thought to be absent from cultural and artistic manifestations, such as children’s literature.

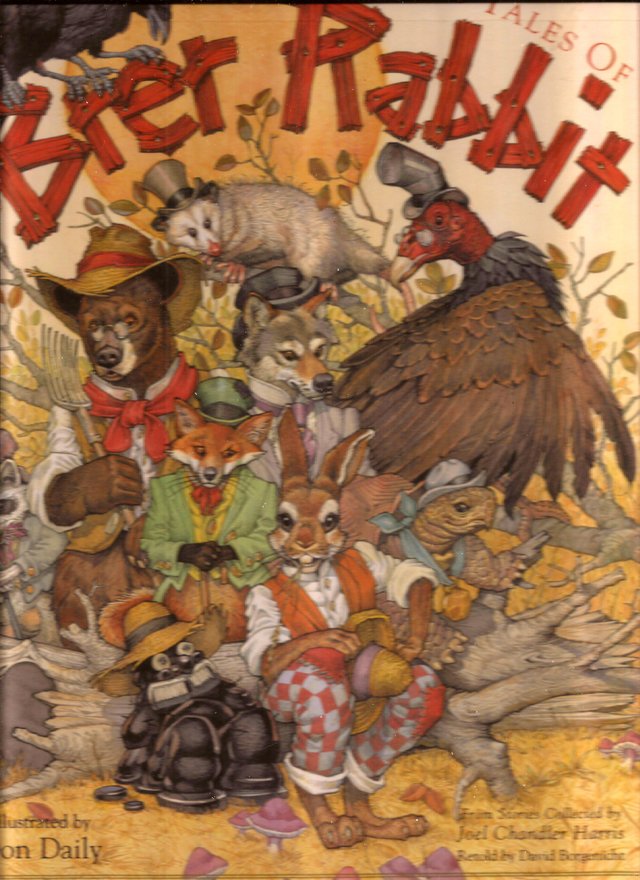

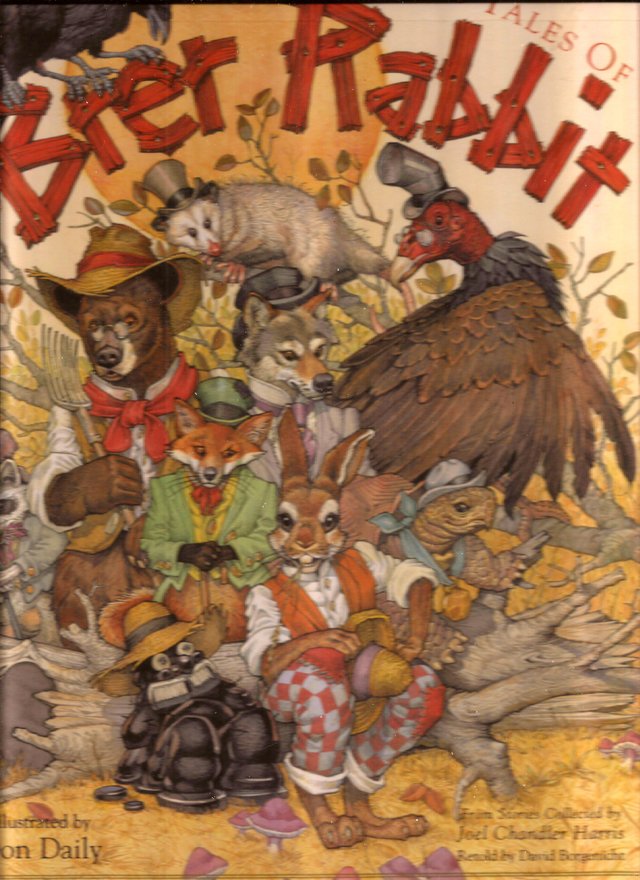

A picture book of stories taken from Chandler Harris' collection, retold by David Borgenicht and illustrated by Don Daily

When the Tio Conejo stories are published without reference to their origin they lose their sense of history. When these stories are presented as a local, modern invention of the viveza criolla (Creole cleverness), the original socio-cultural context is twisted. Thus a rich part of the Venezuelan heritage has been ignored or altered with the stories reduced to simple, naïve, and formulaic folk tales unworthy of serious scholarship.

At some point in the history of Venezuela, the African mark became disadvantageous or even shameful. Venezuelans take for granted that there is some African heritage in their blood. However, because of the high rate of misogyny, no one overtly identifies with any particular race. The sense of harmony is reinforced by the lack of any ethnic conflicts. However, this “racial democracy” has been undermined by a “process of racial bleaching” that “denies the Latin American black the recognizable African characteristics of his physical features and thus his black identity” (Jackson 2). This can partially explain why Tio Conejo has been presented as inherently Venezuelan and unrelated to Africa.

The Venezuelan slaves, although treated poorly, were able to assimilate into the culture. Although abolition was not official until 1854, Simon Bolivar initiated it in 1816. Slaves even took part in the war of independence and enjoyed the post war benefits of land ownership, employment, and manumission. The survival of various African cultures is evidence that black slaves never completely renounced their heritage. If surviving meant modifying the surface of their culture, they did it. But what they valued most, “their cultural focus,” their essence, remained intact.

Afro-Venezuelans took advantage of the Spanish indifference toward intermarriages and religious practices. Thus, they merged and made their “negritude’ disappear as much as possible and even if they decided to keep their color, they converted to the white man’s gospel. By pleasing their masters, Afro-Venezuelans gained their space, a space they filled with African traditions and beliefs.

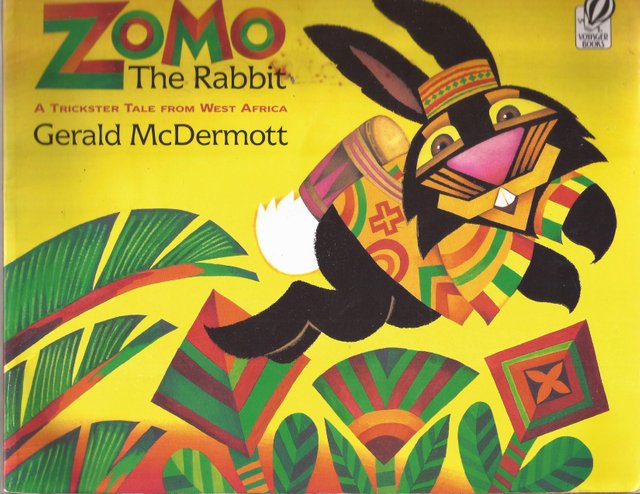

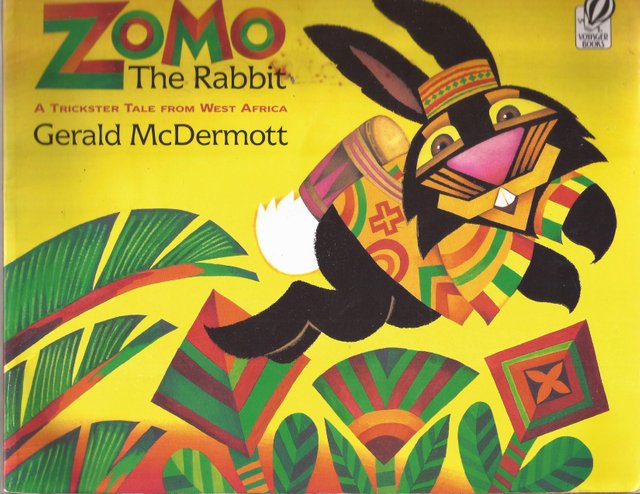

Source

Source

With the telling and retelling of the rabbit tales, no one and everyone can claim authorship. Each country has different narrations with similar themes and even identical stories. Nevertheless, Tio Conejo is portrayed differently, either subtly or dramatically, in every country. Conejo can be a rascal or a faithful companion, an animal moved by hunger or a desire for revenge, or someone following a childish craving to trick for the sake of tricking. He can be a parent or a lustful bachelor with sexually explicit tricks. However, his cunning is allegedly justified, and, unlike Brer Rabbit, his African American cousin, Tio Conejo rarely loses or has his tricks backfiring.

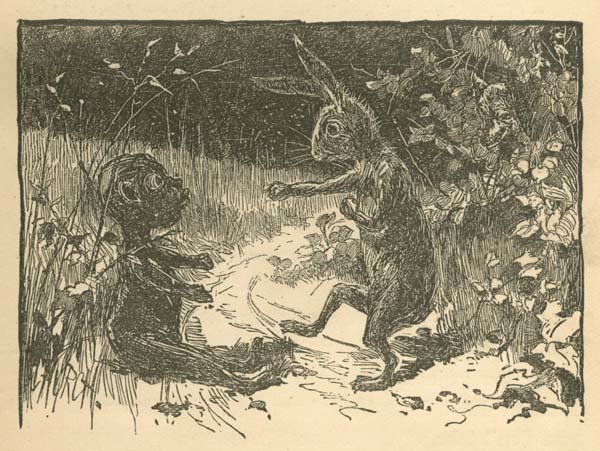

Source

Source

Despite the particulars of the Venezuelan experience, there are generalities reinforcing the historical links among all nations with African slaving traditions. Slavery’s cultural contributions need to be recognized. The tales suffered transformations along the way but, as Roberts says, “cultural change through transformation, however, does not lead to an abandonment of values guiding action recognized by a group, but rather represents an attempt to maintain group values by facilitating adherence to them under new conditions” (12). Through the oral tradition and the printed folktale, the ideals of the African people have been preserved in heroic characters. Thus, Tio Conejo can be seen as the most authentic literary legacy Latin America has received from its African ancestors.

Thanks for your visit.

In the next post, I will provide some examples of the tales so that you can see the similarities an differences between American and Venezuelan versions.

Books images from personal files.

Works cited or consulted

Arraiz, Antonio. Tío Tigre y Tío Conejo. Caracas: Monte Ávila Editores, 1980.

Flores de Tovar, Olga, Cristina Flores, and Gladis Requena. Castellano y Literatura I. Caracas: TEDUCA, 1986.

Harris, Joel Chandler. Uncle Remus. His Songs and His Sayings. New York: Appleton’s 1910.

Jackson, Richard L. The Black Image in Latin American Literature. Albuquerque:

University of New Mexico Press, 1976

Pelton, Robert. The Trickster in West Africa: A Study of Mythic Irony and Sacred Delight. Berkley: University of California Press, 1980.

Rivero Oramas, Rafael. El Mundo de Tio Conejo. Caracas: Ekaré, 1999.

Roberts, John. From Trickster to Badman: The Black Folk Hero in Slavery and Freedom. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1989.

Hello @hlezama, thank you for sharing this creative work! We just stopped by to say that you've been upvoted by the @creativecrypto magazine. The Creative Crypto is all about art on the blockchain and learning from creatives like you. Looking forward to crossing paths again soon. Steem on!

Thanks, @creativecrypto