Tio Conejo: African Roots and Venezuelan Versions

(Part III)

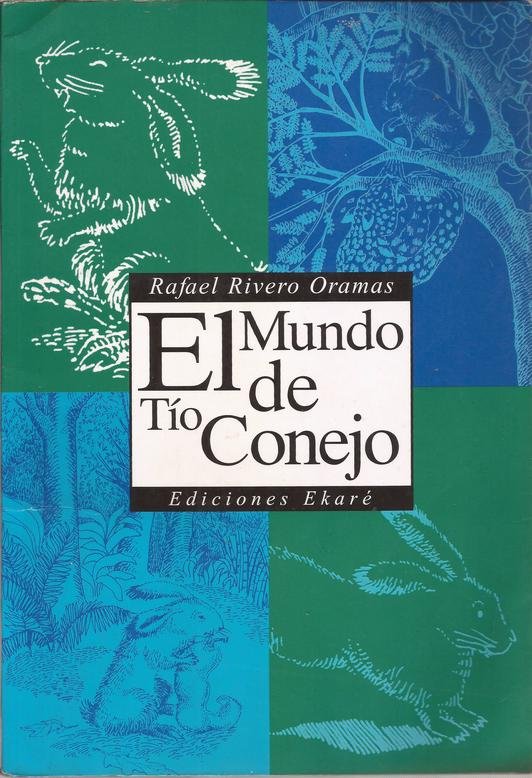

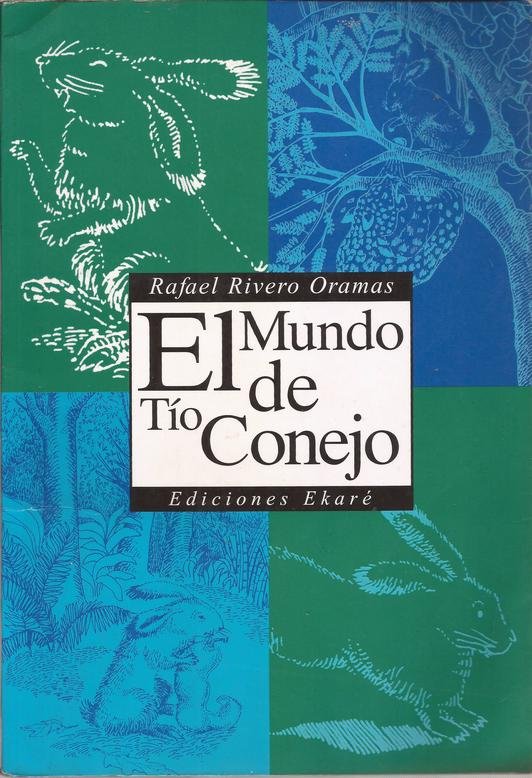

Rivero Oramas’s Tío Conejo's World.

Rafael Rivero Oramas (1904-1992) was perhaps the first Venezuelan writer interested in rediscovering the stories of Tío Conejo. In 1932, he published “Tío Conejo Detective,” a tale that, ironically, has not been anthologized in any of the modern editions. Later, from 1949 to 1967, through the magazine Tricolor, Rivero serialized the stories that he then published in 1973 in book form as El Mundo de Tío Conejo.

Source

Source

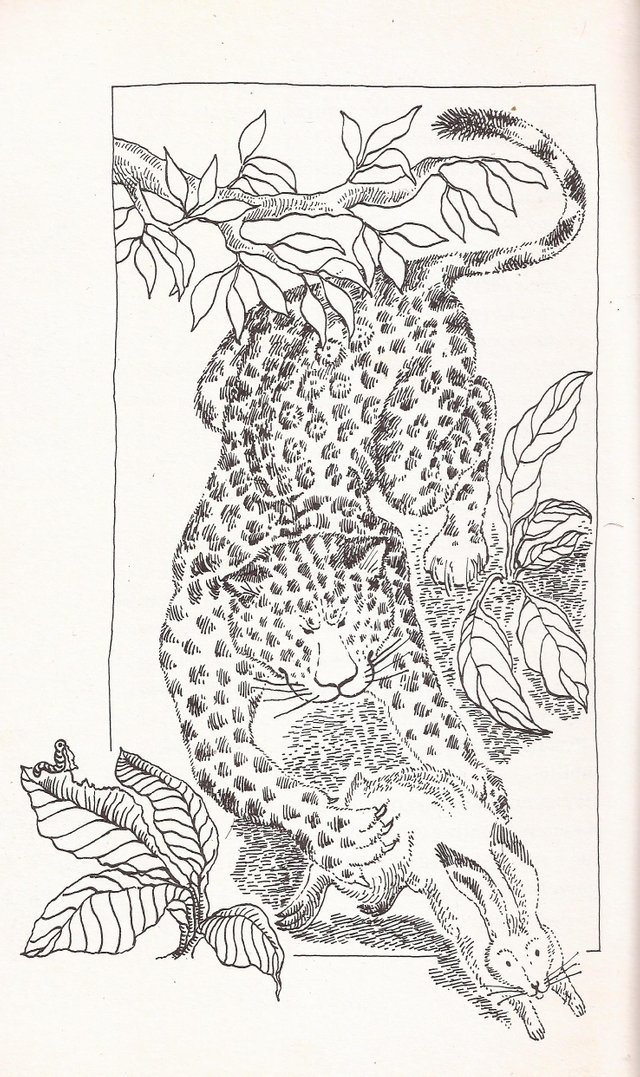

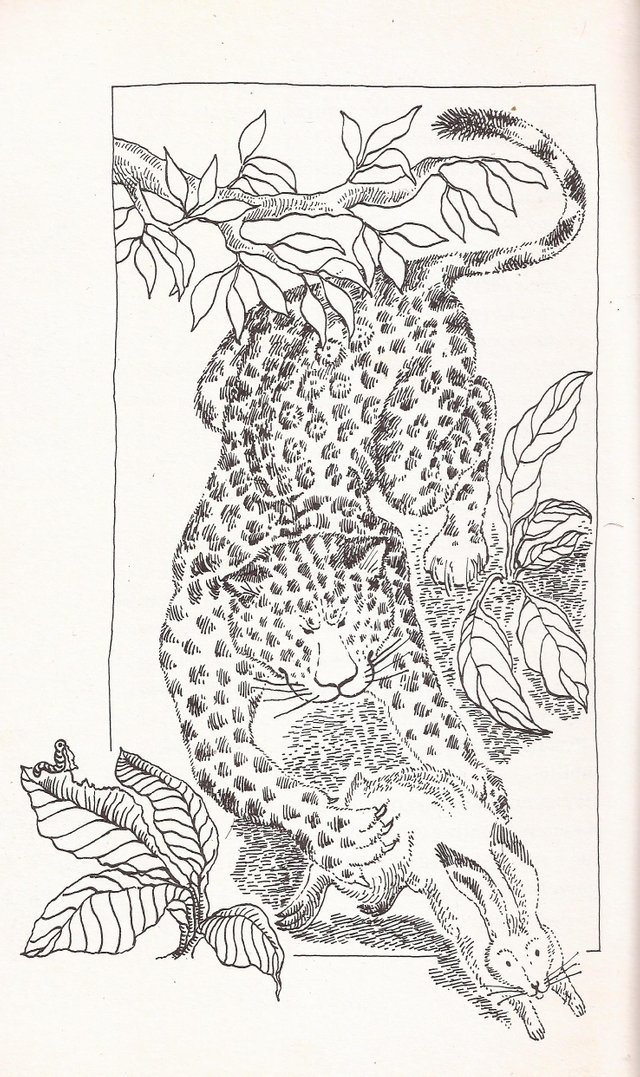

One of the most recurrent motifs in Rivero’s stories is Tío Conejo’s struggle for survival. In most of the tales, he tricks to avoid predation

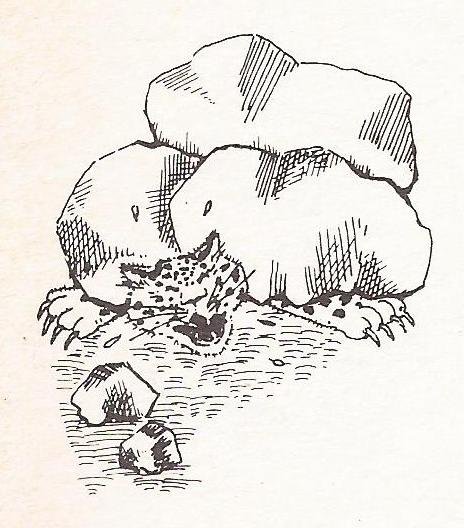

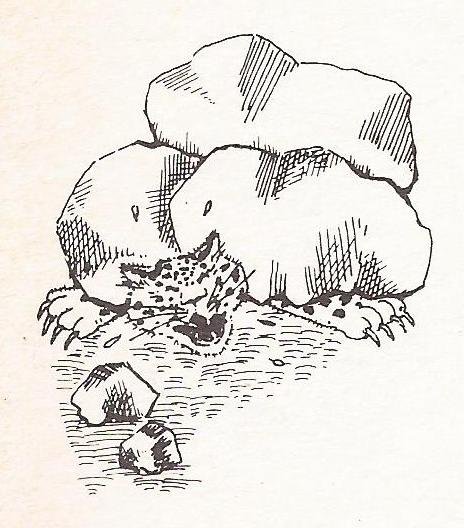

. In “Las Vacas de Tío Conejo,” for instance, Tío Tigre finally catches him after days of persecution. When he is about to be eaten, Tío Conejo, noticing how thin Tío Tigre is, persuades him that eating a little skinny rabbit will not satisfy his hunger. In his stead, Tío Conejo offers Tío Tigre, one of his cows. With this classic appealing to the trickster’s gluttony, Tío Conejo saves his life. He takes Tío Tigre to the bottom of a hill on top of which he says he has his big fat cows. Tío Conejo asks Tío Tigre to wait at the bottom of the hill with his arms opened and his eyes closed while he goes up the hill and sends a cow down. Tío Tigre accepts willingly. Tío Conejo goes up the hill and, instead of a cow, he pushes down a big rock. The rock smashes Tío Tigre, Tío Conejo escapes, and Tío Tigre is left cursing and promising to get him next time. This type of ending is consistent in all the stories of this collection.

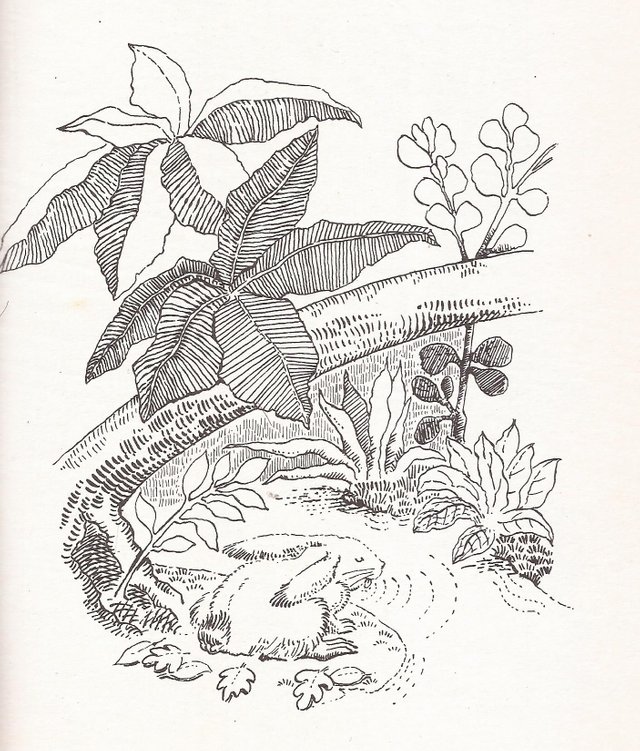

Scanned from personal copy. Illustration by Alicia Ulloa of one of the stories in Rivero Oramas's collection

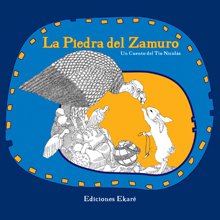

Most of Rivero’s stories have counterparts in other countries with rabbit tales tradition. For instance, five of Rivero’s stories (“Las Vacas de Tío Conejo,” “El Hojarasquerito del Monte,” “El Estornudo de Tio Tigre,” “Tio Caricari,” and “La Piedra del Zamuro”) have been anthologized reprinted and adapted by different authors and in different countries.

Source

Source

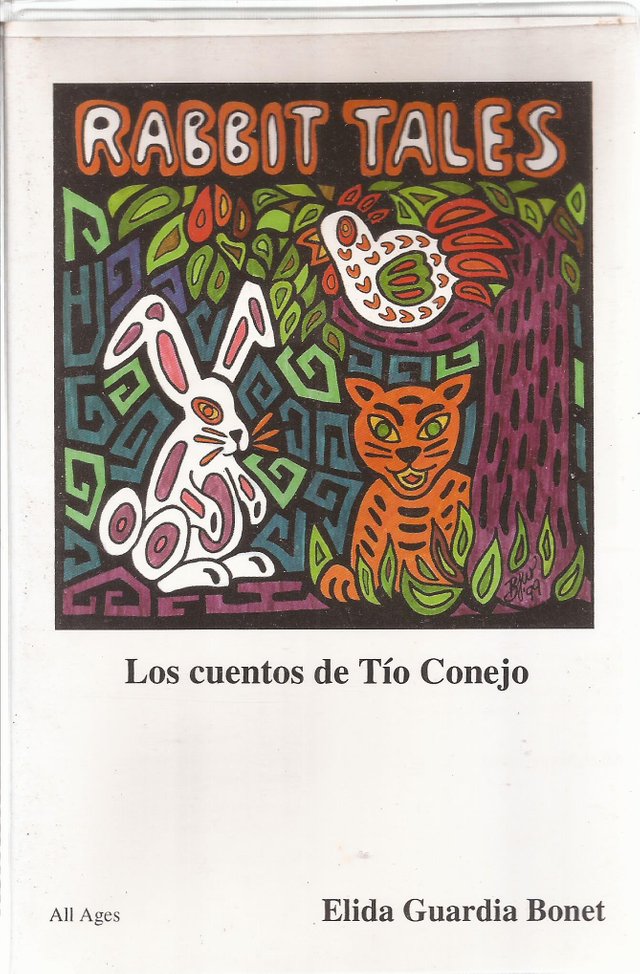

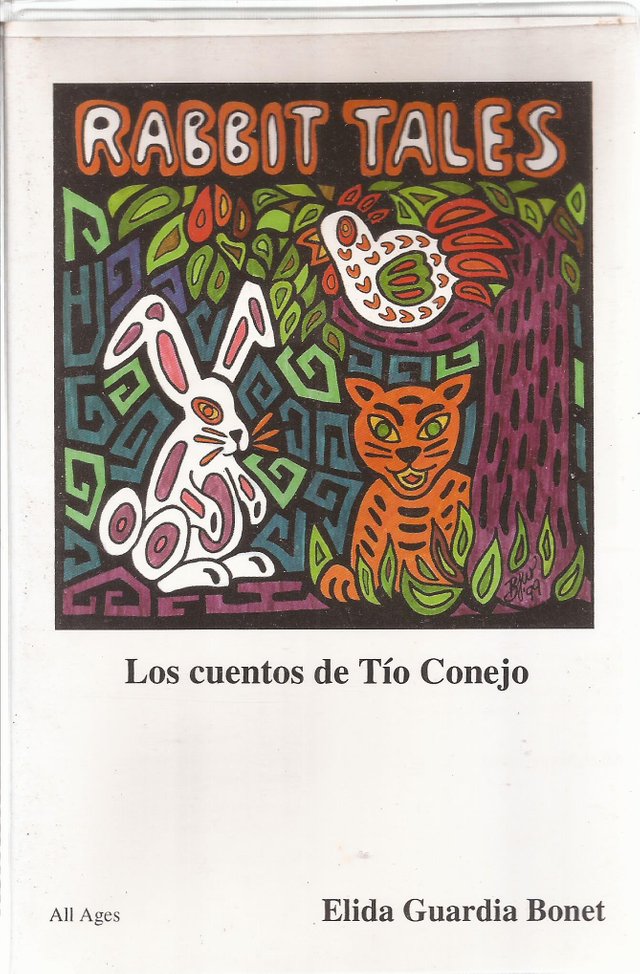

The way the rabbit tales have survived in different cultures shows that there must exist some kind of symbiotic relationship between folklore and culture-specific features that historically shape nations and peoples. In the same way societies re-invent folklore, folklore can re-define society and its values. “La Piedra del Zamuro,” (The vulture’s stone) for instance, one of Rivero’s stories, is a variant of Rabbit Wishes, adapted by the Cuban-American Linda Shute, Rabbit Wants to be Big! by the Puerto Rican-Panamanian-American Elida Guardia Bonet, and Zomo the Rabbit: A Trickster Tale from West Africa, by American author and illustrator Gerald McDermott. In this story there are important cultural, moral, and ethical issues that are addressed differently by different authors in different cultures. This is basically the story of how the weak trickster animal acquired the skills to defend himself from stronger animals.

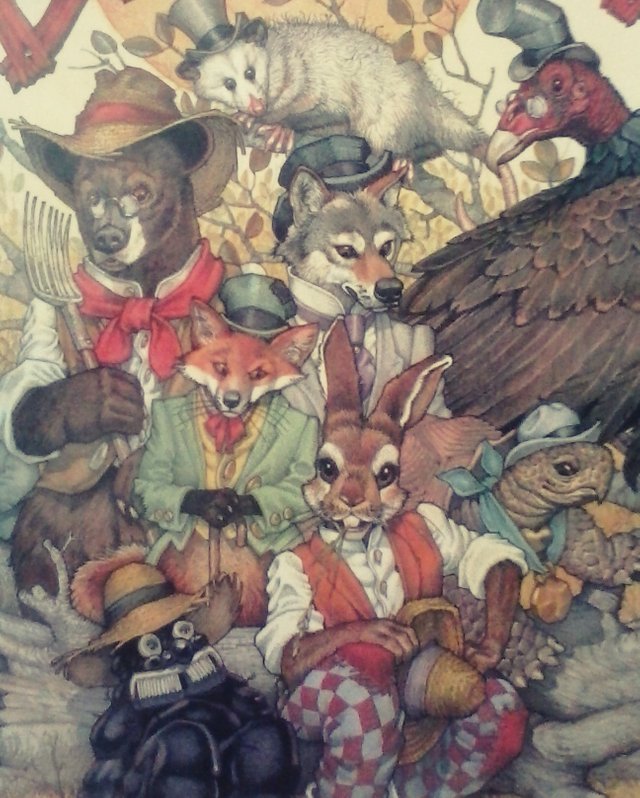

Scanned image of my copy of Guardia's audio cassette edition

In terms of the religious approach to the tales, both Rivero and Arráiz are similarly secular. Unlike the other versions mentioned, Rivero's Tío Conejo does not speak to God. Instead, he complains to the wise turtle, Tío Morrocoy, about his weaknesses. Tío Morrocoy sends him to talk to the Rey Zamuro, king vulture, who is said to possess a magic stone that will give him the tools to deal with his enemies.

This change in the Venezuelan version evidences the extent to which Afro-Venezuelans blended magic and religion. The religious syncretism that took place in the new world demystified the African stories and at the same time secularized the Western religious beliefs. It manifested differently in every country depending on the influence or level of assimilation of Christianity. There are few instances in Tío Conejo’s Venezuelan renditions where divine or religious elements are addressed and, to my knowledge, God or any other form of divinity is never mentioned. The multiple faces of Tío Conejo are, then, a byproduct of the cultural blending that took place in America.

There are other variants in “La Piedra del Zamuro.” In Shute’s adaptation, God demands three things to grant Tío Conejo’s wish: a feather from an eagle, an egg from a serpent, and a tooth from a lion. In Rivero’s tale, the vulture requests four things: a tooth from a crocodile, a snake, a hair from a lion, and tears from a tiger. Some authors have made erroneous generalizations regarding the violence in the trickster tales as something inherent to certain cultures. Although in all these variants there is certain violence implied, like banging teeth out with stones, Shute affirms that this Tío Conejo, “closer in spirit to the African American character Brer Rabbit” is not as bloody and aggressive as the Nicaraguan or the Guatemalan who “collects the skins of monkeys, alligators, and tigers in order to claim his reward” (24). This is arguable considering all the discussion around Chandler Harris’s heavy editing of the stories to soothe Brer Rabbit’s violence in some of the original tales, including even cannibalism. “Cannibalism was an issue almost as sticky as the Tar Baby…” (Chang 38). Also Shute inaccurately affirms, “While Brer Rabbit always emerges victorious from his exploits, none of Tio Conejo’s clever schemes work out quite as he expects.” An overview of any of the collections of the Brer Rabbit stories is enough to realize that this is precisely the kind of trickster that tends to be tricked (for some examples see Lester 29-32, 35-7, 65-7).

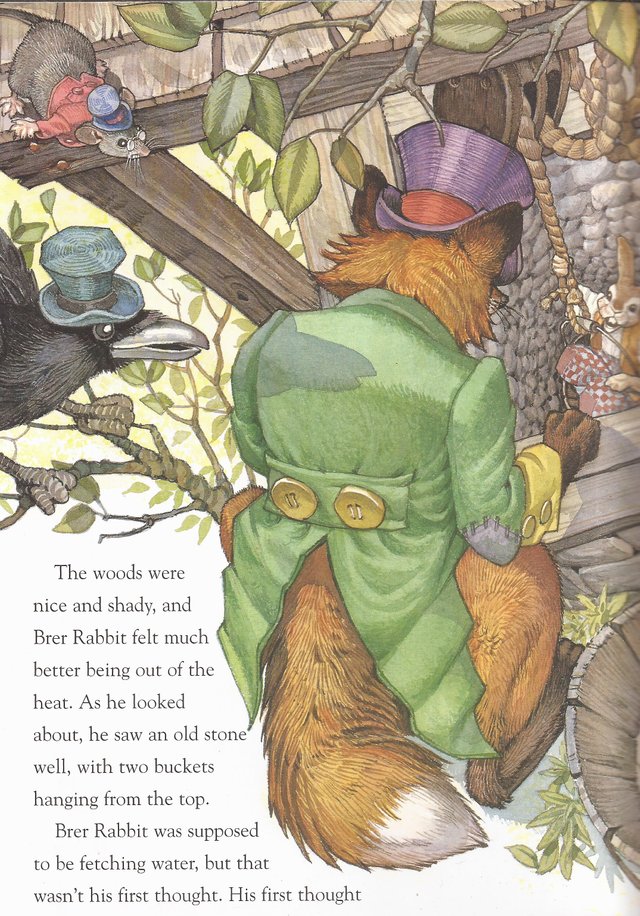

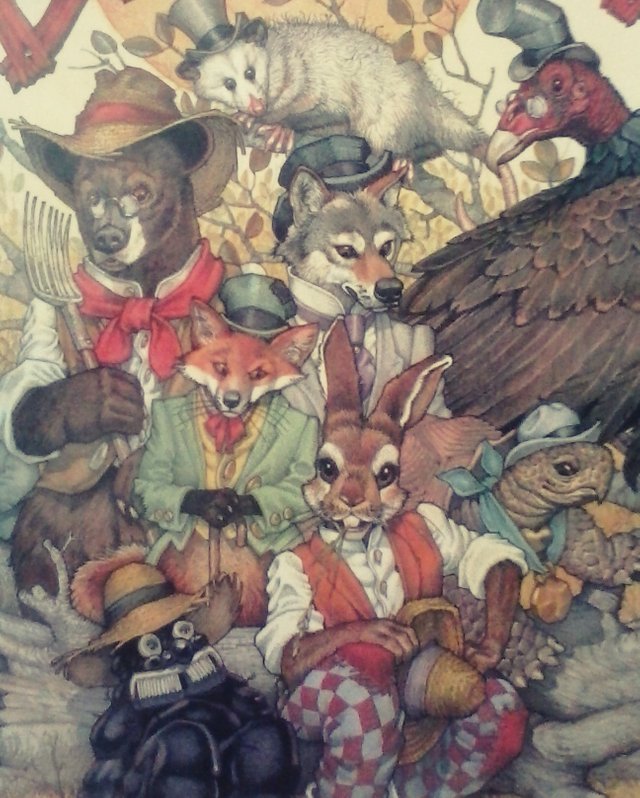

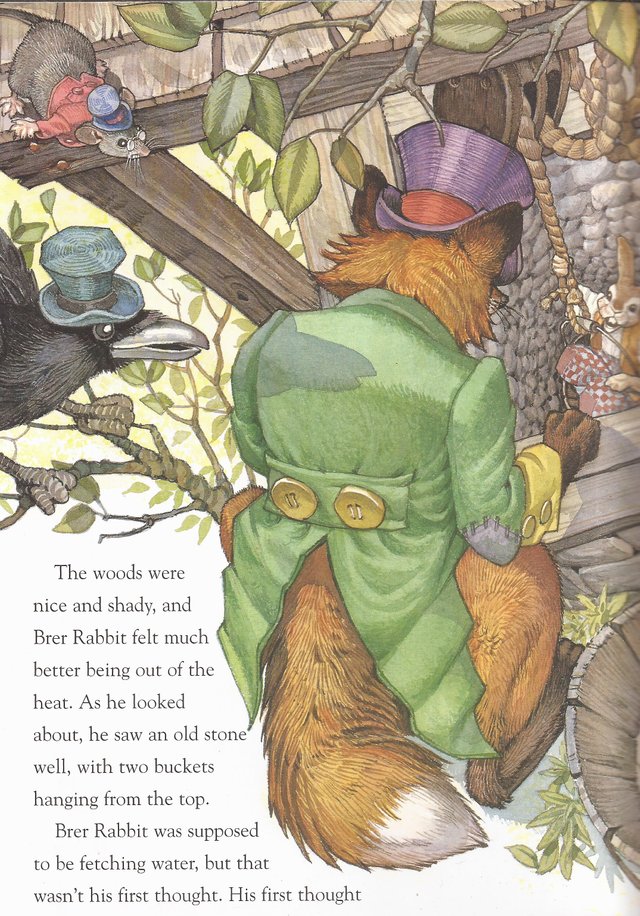

Scanned image from Borgenicht and Daily's picture book. My copy.

In Shute’s “Rabbit Wishes,” as in Guardia Bonnet’s “Rabbit Wants to Be Big,” Tío Conejo is tricked by God. Originally small with short ears, Tío Conejo does not get as big and strong as he was promised; instead, he only gets his long ears. Thus, their stories become the kind of “how-things-came–to happen” folk tales. In Venezuela these kinds of stories are more characteristic of the native Indians’ mythology. In Rivero’s version, although Tío Conejo finds out at the end that the vulture’s stone is not magic at all, he does not feel tricked. Instead, he learns from the vulture that, even without the magic stone or any other kind of special powers, he can defeat bigger animals because he has his wit to outsmart them. In this respect, Rivero's Tío Conejo is not only secular, but also individualistic.

In fact, the Venezuelan Tío Conejo can be considered one of those always-victorious tricksters. Unlike his African American cousin, at least in the stories that have survived and passed on, Tío Conejo is never tricked. However, the similarities with Brer Rabbit are remarkable. In fact, morphologically speaking, all the stories of this collection follow the six elements discussed by Lee Haring in “A Characteristic African Folktale Pattern” (1972). That is, there is an initial false friendship, a contract or agreement between the animals involved in the story, a violation of the contract, a trickery followed by deception, and the trickster’s resulting escape. This pattern can be more easily appreciated in Rivero’s stories than in Arráiz’s.

Rivero’s story, “El Hojarasquerito del Monte,” has been widely anthologized and adapted in both Latin American and African American literature. In African American collections, this story has been entitled “How Brer Rabbit Became a Scary Monster” (Lester 119-22), also “Brer Rabbit’s Astonishing Prank” (Amin 38-42). Although in the Venezuelan oral tradition, this story narrates how Tio Conejo tricked Tia Zorra, Aunt Fox, Rivero has placed Tio Tigre in the fox’s place. He does this because in most of the oral narrations where Tio Conejo tricks a female animal, there is some kind of sexual violence involved, something that would not have been acceptable in print (especially if marketed as children’s stories).

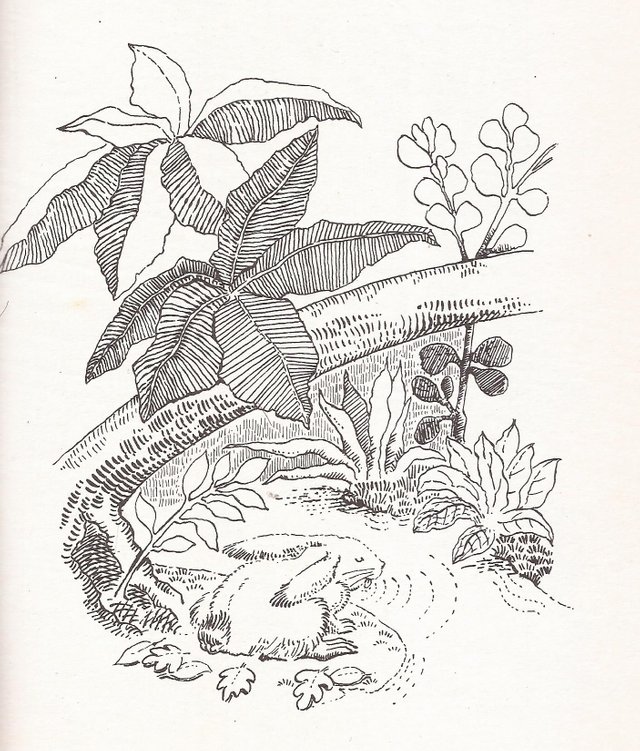

Unlike the African American version, where Brer Rabbit accidentally pours the honey on himself at Brer Bear’s, gets dried leaves attached to his body, and takes advantage of it to scare every animal he runs into, Tío Conejo is forced to have this transformation so that he can drink from a pond guarded by Tío Tigre. Thus, Rivero tries to emphasize survival as the motive for Tío Conejo’s tricks. But, in most of the stories the situations in which Tío Conejo’s life is at risk are caused by Tío Conejo's previous pranks. Rivero adds at the beginning of the story an incident that caused Tío Tigre’s animosity towards him. Then, it happened that one day Tio Conejo tricked Tio Tigre with some guamas (fruit from the guama tree) making him bite his own tale and had to hide for days. Tío Conejo decided to camouflage himself so that he could drink without being noticed. When Tío Conejo gets to the pond, Tío Tigre does not recognize him and asks him what kind of animal he is. He does not answer until he has quenched his thirst, then he runs away.

In Rivero’s Tío Conejo’s world, then, there is a dog-eats-dog dynamic that evokes the tensions among slaves when some of their own people became overseers and in order for them to get the white man’s favor or confidence, these watchmen had to betray their fellow slaves telling on their attempts to escape, theft of food, or alleged laziness at work.

The recurrence of this kind of story evidences the negative repercussions the trickster’s behavior could have. Friendship has always been a slippery concept in trickster tales and Tío Conejo’s stories are not the exception. He is surrounded by false friends who tend to plot against him to gain Tío Tigre’s favor. Then, the whole betrayal becomes a kind of vicious cycle. Rivero’s Tío Conejo, though, is unstable and driven by passions. He can save a friend’s life in the morning and trick him in the evening. Although

issues like friendship, loyalty, and social order are at stake

, Rivero’s stories are not intended to elicit any of them. If anything,

these stories makes us reflect about the fragility of such concepts and how contingent they are to people’s personal interests.

Thanks for your visit.

In the next post on the series, we'll see how Tío Conejo gets politicized in Arráiz's novel-like collection.

Works cited or consulted

Amin, Karima. The Adventures of Brer Rabbit and Friends. London: DK, 1999.

Arraiz, Antonio. Tío Tigre y Tío Conejo. Caracas: Monte Ávila Editores, 1980.

Borgenicht, David, Illustrations by Don Daily. The Classic Tales of Brer Rabbit. Philadelphia: Running Press, 1995.

Chang, Linda S. “Brer Rabbit’s Angolan Cousin: Politics and the Adaptation of Folk Material.” Folklore Forum (1986): 19:1. 36-51.

Flores de Tovar, Olga, Cristina Flores, and Gladis Requena. Castellano y Literatura I. Caracas: TEDUCA, 1986.

Guardia Bonett, Elida. Tío Conejo (AudioCassette). Colleyville: Zaratí Press, 1999.

Haring, Lee. “A Characteristic African Folktale Pattern.” African Folklore. Ed. Richard M. Dorson. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1972.

Harris, Joel Chandler. Uncle Remus. His Songs and His Sayings. New York: Appleton’s 1910.

Jackson, Richard L. The Black Image in Latin American Literature. Albuquerque:

University of New Mexico Press, 1976.

Lester, Julius. The Tales of Uncle Remus. The Adventures of Brer Rabbit. New York: Puffin Books, 1987.

McDermott, Gerald. Zomo the Rabbit: A Trickster Tale from West Africa. New York: Voyager Books, 1996.

Pelton, Robert. The Trickster in West Africa: A Study of Mythic Irony and Sacred Delight. Berkley: University of California Press, 1980.

Rivero Oramas, Rafael. El Mundo de Tio Conejo. Caracas: Ekaré, 1999.

Roberts, John. From Trickster to Badman: The Black Folk Hero in Slavery and Freedom. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1989.

Shute, Linda. Rabbit Wishes. New York: Lothrop, 1995.