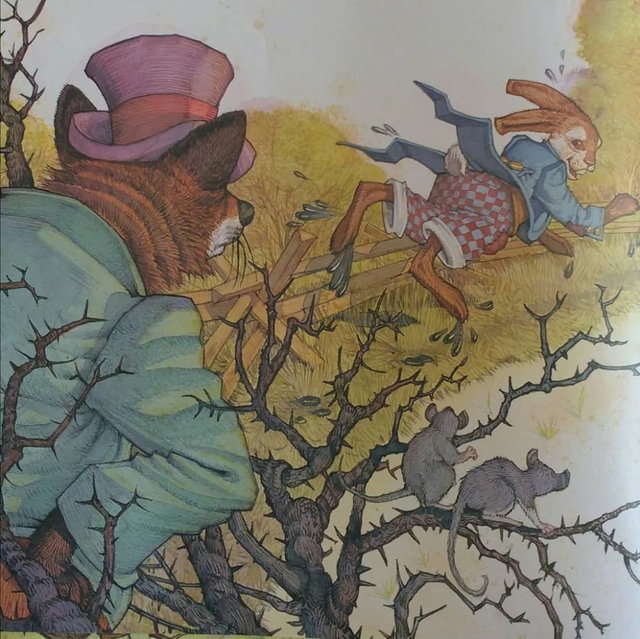

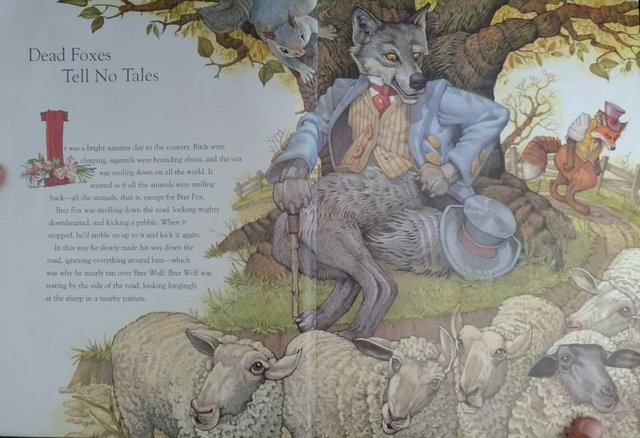

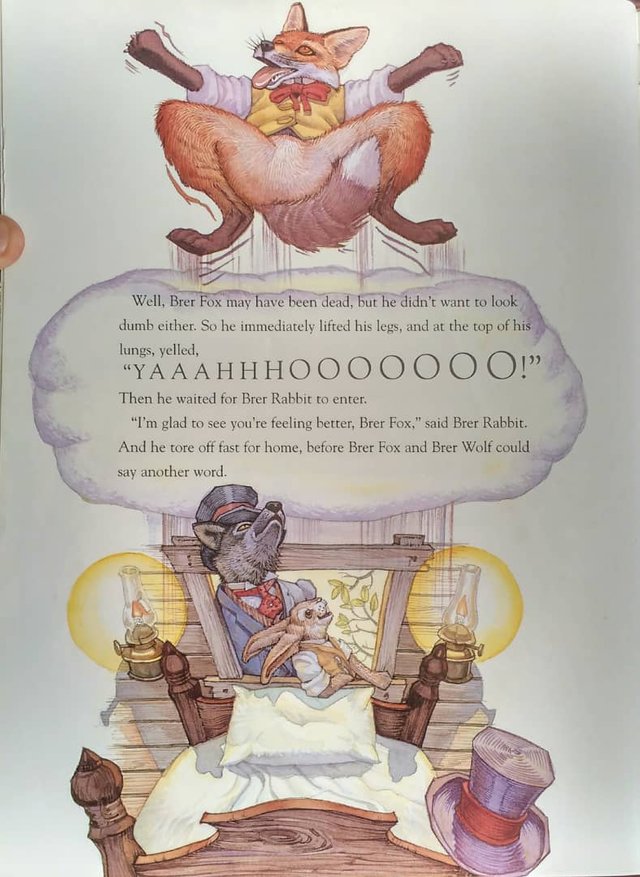

In “Tío Tigre Enfermo,” Arráiz elaborates from the widely known and adapted story in which Tío Tigre pretends to be dead to make Tío Conejo come to his house and capture him (Rivero’s “El Estornudo de Tío Tigre”, Borgenicht and Daily's "Dead Foxes Tell no Tales"). Arráiz satirizes issues such as vanity and appearances, while critiquing the ethical and social issues in Venezuela’s health system.

In Arráiz’s story, Tío Tigre pretends to be ill. The story begins with Tío Tigre and Tío León challenging each other’s athletic abilities. Tío León defeats Tío Tigre in all competitions; thus, Tío Tigre decides to trick Tío Leon making him jump over cardones. Inexperienced in that territory, the lion gets a cactus thorn in one of his paws. The story turns, then, into a chaotic theatrical representation of Venezuela’s health system. None of the animal doctors knew how to deal with the lion’s emergency. Each doctor came up with a different idea of how to treat the lion’s painful condition. Tío León, tired of so much medical nonsense, left the hospital and went to a certain female monkey who pulled the thorn out with a simple needle (can also be read as a critique to the overemphasis on science and a call to go back to the wisdom of folk medicine).

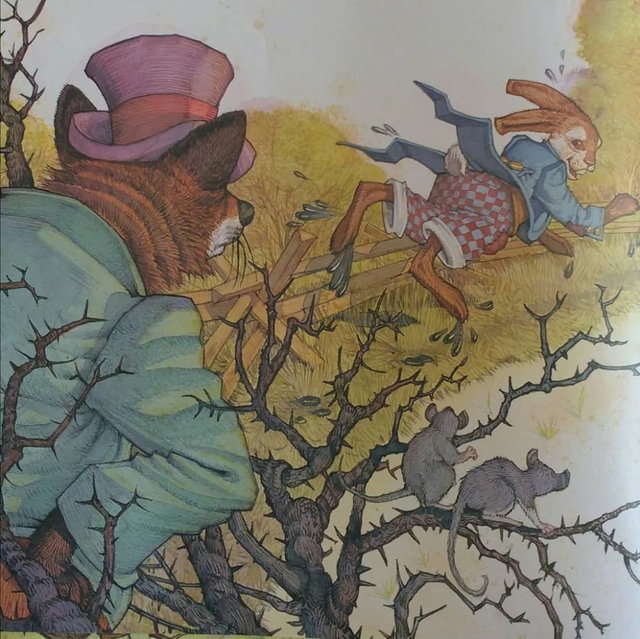

Tío Tigre witnessed it all and swears not to fall on any doctor’s hands. One of his advisors proposes him the idea of pretending to be sick so that Tío Conejo comes to visit him and Tío Tigre can catch him. What Tío Conejo does, then, is that he goes to visit but takes with him the most experienced doctors in town, that is, the ones who treated the lion’s thorn. When Tío Tigre sees the company, he panics and runs away.

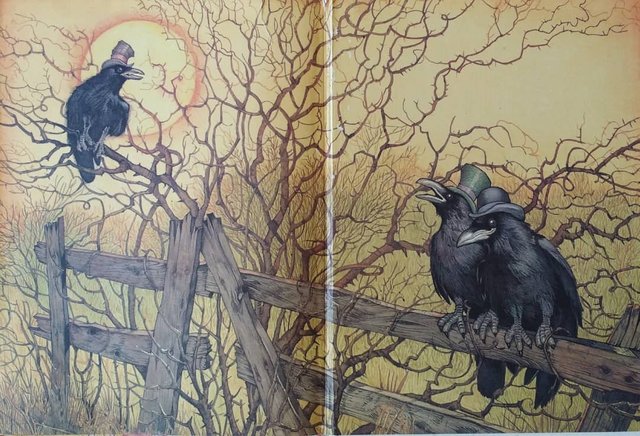

In “La Fundación,” Tío Conejo has not been seen for a while. Some animals comment on the peace Tío Conejo's disappearance has brought to them. They say Tío Conejo was an agitator. Other animals complain about how boring things are now without Tío Conejo. They consider him as an “outlaw hero”. They want Tío Conejo back. This conflicting diatribe is illustrated by Roberts when he affirms that “the creation of bandits or outlaw heroes arises when the way of life of one segment of a society is threatened by natural disaster or the law, while another segment of the society seems unaffected or even prospers from the same condition” (6).

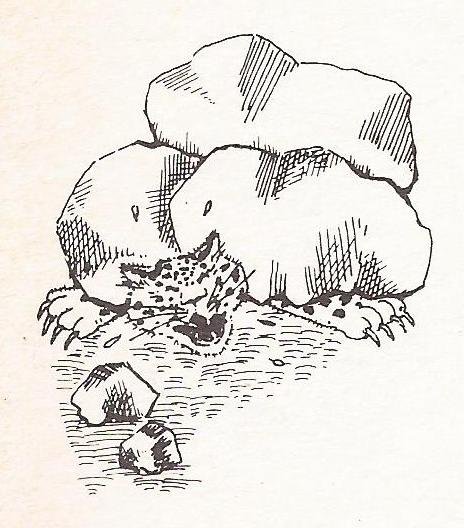

Some animals, suspicious about the silence surrounding Tío Conejo’s disappearance, talk about political conspiracies and rumors of gun trafficking (a common concern in the Venezuela of the 30s and 40s and even later). One day Tío Tigre gets to La Fundacion, an abandoned human settlement. There, he finds Tío Conejo sleeping. At this point of the story Arráiz digresses to tell how the settlers got there, how malaria killed their women and children, and how the survivors were forced to leave. He describes how the greenness of nature invaded (or rather re-conquers) what civilization had altered. The end of the story is Arráiz’s adaptation of “Las Vacas de Tío Conejo.” When Tío Tigre tries to eat the sleepy rabbit, Tío Conejo tells him about some fat cows remaining from the old settlers’ livestock. Tío Conejo leads Tío Tigre to the bottom of a hill and, as in Rivero’s story, smashes him with big rocks.

Arráiz’s final story is “El Toro Parapara.” This bull, animals say, is an invincible and untamable creature. He lives in a place no one can reach; he is nobody’s friend. When Tío Tigre has to tell his friends about his injuries (caused by Tío Conejo's ‘cows’) he tells instead that such injuries were in fact caused by this terrible bull. He narrates how he heroically confronts the bull and miraculously escapes. Tío Tigre’s allies support his story with the condition that Tio Tigre would support similar “heroic” deeds they have been fabricating. Arráiz parodies here the numerous stories of clay-feet caudillos that became celebrities, almost legends, thanks to the societies of accomplices they created around them.

Tío Tigre is, then, proclaimed a national hero. They erect statues in his honor. Those animals that contradict or question the official story are declared traitors. When they learn that Tío Conejo is telling a different story, they decide to take him to court. The animal society is, thus, divided among those who support Tío Tigre and those who trust Tío Conejo. They start talking of revolution. The war among animals become imminent and each party has a leader to follow.

But, Tío Conejo is far from becoming a caudillo. To pacify his followers he tells them about the dream he had by La Fundacion. In that dream, he became Tío Tigre. He gained power and became ruthless, while Tío Tigre became the underdog. Tío Conejo tells his friends,

you had become my ministers, my secretaries, my assistants; you sustained my authority, but the bonds of friendship, affection and cordiality did not longer exist between us. If you were with me it was only […] because of the fear that a superior force inflicts.

As the armies waited for the orders to start battling, Tío Conejo cried,

This is not the way! We’ll shed blood, we’ll destroyed lives; we’ll depose with violence a government that has been sustained on violence. Then, we’ll need violence to sustain our government, thus violence will continue reigning among the otherwise placid lives of animals” (200).

Source

Source

Tío Conejo decides then to leave. He becomes the classical solitary trickster we know now from other stories. His acknowledging that he can become a disturbing agent for the wellbeing of the community makes him choose exile.

It is true, then for the Venezuelan socio-historical reality that “a group for which culture-building has proceeded through warlike confrontations would be more likely to conceptualize an individual as heroic who selects warlike actions and displays a warlike personality in the face of any threat to group values” (Roberts 7). Consequently, Tío Conejo is ultimately perceived as “weak and ineffectual” because he chooses to respond differently to those threats.

By the time Arráiz publishes Tío Tigre and Tío Conejo, though, there was a relatively peaceful atmosphere and a desire to overcome the violence of previous decades. Those Venezuelan authors who published folktales in the forties, were urged to be politically correct. In times of social discord, tales that inspire humor, solidarity, or moral lessons were preferred versus those that emphasized individualism or violence. Arráiz knew, however that the injuries of centuries of war had not completely healed and that the country had founded its cultural identity on erroneous values and heroes which only prolonged the never ending cycle of hostility.

Source

Source

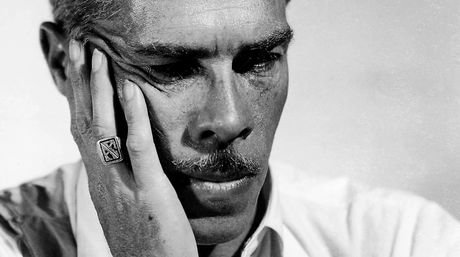

Arráiz himself became the victim of a human and political reality that overwhelmed him. In 1943, when he became the director of El Nacional, one of Venezuela’s most prestigious newspapers, he promised his readers a zealous defense of the freedom of speech. He also declared that only the Venezuelan people would become the judges of his work. In his first editorial, he said, “The word we bring to you is not of piece or complaisant friendship, but of war: we come to battle lies and corruption, wherever they exist; we come to vindicate [merits and efforts] and censure ineptitude” (in Araujo 9-10). He was willing to give a war, but that war was fought with words and guided by reason.

Source

Source

Rómulo Betancourt (1908-1981). President (1945-48, 1959-64)

Venezuelans generally do not make heroes out of pacifists. However, Arráiz’s years in prison must have taught him more than one lesson as to be willing to satisfy people’s expectations. He had experienced himself the change from a young inexperienced militant to a more mature and tactful intellectual and public figure. His Tío Conejo seems subversive at the beginning, but eventually he turns into a less confrontational character. Venezuelan history is full of leaders who, after gaining followers, are forced to leave the country and abandon their causes to save their lives or avoid greater damages to their causes. Venezuelans tend to look with skepticism at this kind of leaders, unless their retreat is a scheme for future counterattack. (e.g. Simón Bolivar, the liberator or Rómulo Betancourt, the so-called father of Venezuelan democracy, who planned from exile their successful counterattacks).

Unfortunately, when Arráiz’s Tío Conejo quits his role as a social leader he seems to do it for good. From then on, according to Arráiz, Tío Conejo becomes the shy, evasive, and individualistic trickster figure we know today. Arráiz’s Tío Conejo never became popular among the general audience. His tricksterism did gain people’s favor, though. In fact, a popular Venezuelan saying suggests that if a Venezuelan does not become a trickster from childhood, they will not make it into adulthood (… pendejo se muere chiquito). It is as if we have never been able to overcome the time when tricksterism was associated to survival.

Antonio Arráiz’s work and his contribution to trickster studies should continue to be explored in more details. In his work there are more connections to the folkloric manifestation remaining from the African presence in Venezuela than it appears to the casual reader. These manifestations are as varied and complex as the racial mixture resulting from the historical and human connections that forged this nation. The African tricksters have survived, but they have shape-shifted. Their deeds are no longer told and retold around a fire, to the whole community, and in an animated dramatization of never-ending stories. Now, they continue transmitting culture and lore, but they are frozen in textbooks, manipulated by the editing eye of the new breed of storytellers. Fortunately, every generation of storytellers produces an Rivero who will sell Tío Conejo as a badman kind of rabbit trickster, and an Arráiz who tries to turn Tío Conejo into an outlaw hero; the kind of trickster who cares about his community, defies authority, comes to help wherever there is injustice, and then disappears so that people can tell usually ambiguously inspiring stories until this stories find connections. And, these stories shall have no end.

Thanks for your visit.

Works Cited or Consulted

Araujo , Orlando and Oscar Sambrano Urdaneta. Antonio Arráiz. Caracas: EBVC, 1975.

Arráiz, Antonio. Tío Tigre y Tío Conejo. Caracas: Monte Ávila Editores, 1980.

Borgenicht, David, Illustrations by Don Daily. The Classic Tales of Brer Rabbit. Philadelphia: Running Press, 1995.

Pelton, Robert. The Trickster in West Africa: A Study of Mythic Irony and Sacred Delight. Berkley: University of California Press, 1980.

Rivero Oramas, Rafael. El Mundo de Tio Conejo. Caracas: Ekaré, 1999.

Roberts, John. From Trickster to Badman: The Black Folk Hero in Slavery and Freedom. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1989.

Source

Source

Hello friend, we grew up reading and telling the stories of uncle rabbit and uncle uncle tiger. I never thought that behind these fables there was a complex meaning.

Yep. There's a complex web interwoven around these seemingly simple tales.

Thanks for stopping by.