Precursor to the Mỹ Lai Massacre: 1968 Phong Nhị, Phong Nhất_14

Chapter 14: The Cruelest Assault

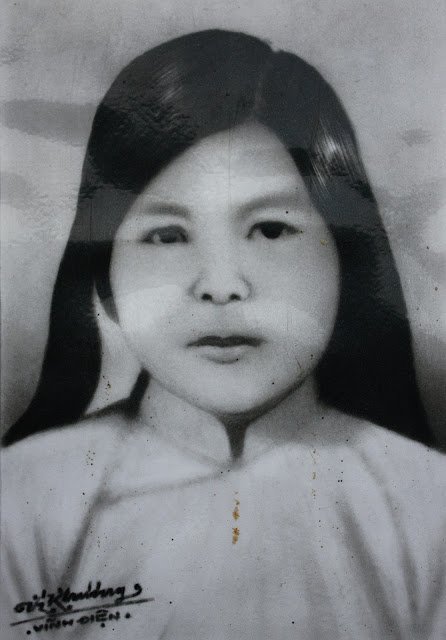

- Nguyễn Thị Thanh, reduced to the letters F and G

The two photographs of Nguyễn Thị Thanh, taken by a U.S. Corporal, thereafter referred to by letters of the alphabet, F and G. The explanation included had been, “The woman, still alive with her breasts mutilated.”

“The punitive forces went around to each home, dragging its residents out and gathering them at the Sooryong Elementary School yard. It was before all the classrooms were built, so there was a lot of firewood in the yard. They beat us brutally with the firewood, and stripped us naked, both men and women, for no apparent reason. I was 41 years old at the time, but there was no time to even be embarrassed. I could only do as I was being told. They continued to beat our naked bodies with the firewood. Soon enough though, they stopped being amused by the act, and they called out a young woman and a man and commanded them to do it on the spot with everyone watching them. Those guys were subhuman. The man and woman stood there, not knowing what to do, so they were beaten some more. Just as the sun began setting, they took out a gun and shot four of the residents that they were dragging out” (May 30, 1948; testimony of an old man from Chungsoo, Hanlim, Jeju City.『Testimonies from the Jeju Uprising』(Jemin Daily, Jeon, Yewon, 1995).

“There was blood everywhere, an old woman, who was trying to stop them, was stabbed with dagger, female students, who were practically stripped naked, had their breasts stabbed with knives, and even a four-year-old child was killed under their boots. Those citizens and students who were killed or close to being killed were taken away on a camouflage patterned truck, and the streets became a scene of utter carnage (『May 18th Gwangju Democratic Uprising source book』, May 26, 1980, Citizens of Gwangju, Gwangju Publication 1988).

“(May 19, 1980) The citizens of Gwangju were ignited after hearing that a female student was found killed near the fountain at Gwangju Station, naked with her breasts cut off (a deputy commander in chief of the martial law office attested to there being a corpse to the likes of this description, but insisted that it couldn’t have been done with a sword, so that it must have been a subversive who used his razor) (Ibid).

“From the 19th to the 22nd, when the match between the citizens and the airborne troops was most competitive, the emergency room was obviously filled with patients, but there were also mattresses laid out for patients all throughout the hospital, including waiting rooms, corridors, and even next to the reception windows. As for the rumor regarding the young lady whose breast were cut off by the sword of the airborne troops, I did treat a patient in exactly that condition. Choi, Mi-ja (19 at the time) was brought to the hospital with stab marks on her breasts and back, in the afternoon of the 19th. The precise location of her scar was between her armpit and breast, so by that alone, it is difficult to say whether the martial law officer had intentionally aimed to sever her breast.” (〈Gwangju Daily〉January 14, 1989, Testimony of Dr. Oh, Bong-seok Jeonnam University Thoracic Surgery Department).

It was 20 years after the Jeju Uprising took place in 1948, and 12 years before the Gwangju Massacre that took place in May of 1980. February 12, 1968 Vietnam was chronologically situated between the Jeju and Gwangju incidents. That day, around 2:00 pm, in Phong Nhị and Phong Nhất , the Jeju Uprising was reenacted, and the Gwangju Massacre, portended. 19 year-old Nguyễn Thị Thanh lay naked in the fields, groaning in pain. Her breasts were mutilated and bleeding, as well as her left arm. The marines who entered the villages, much like the punitive forces who infiltrated Jeju and the airborne forces that would later be dispatched to Gwangju, were heinous. The punitive forces of the past, the marines of the present, and the airborne troops of the future, all bore the same appearance and spoke the same language. 1948, 1968, and 1980. Fear gripped the besieged villages and cities. They shot their guns, brandished their swords and threw hand grenades. Sexual abuse was another commonality. Nguyễn Thị Thanh was a victim of sexual abuse by the Korean troops of 1968.

Until April of 2001, when a Korean journalist brought a photograph containing her and confirmed her name, she was but an unidentified victim, referred to using indescript letters of the alphabet, F and G. In both photographs F and G, she was described as, “The woman, still alive with her breasts mutilated,” by U.S. Corporal J. Vaughn. Vaughn witnessed the burning of the villages from afar, and later came with the South Vietnamese militia and U.S. platoon. He was taking vivid photographs from the entrance of the village when he came across Nguyễn Thị Thanh. She was in dire conditions. Her shirt was torn, and she was bleeding heavily from her breasts and arms. He could tell how sharp the sword had been. Yet she was still breathing. He took a photograph of her from the right and from the front before calling the South Vietnamese militia to come transport her.

Nguyễn Thị Thanh was taken to the hospital in Da Nang. Her father Nguyễn Dân(41) heard the tragic news from Da Nang. But it wasn’t just that his eldest daughter Thị Thanh was severely injured; his wife, Phạm Thị Cam(40), and fourth daughter, Nguyễn Thị Hường(11) were killed immediately, and his 5-month old son, Nguyễn Điền Cạnh, was also heavily injured. His family had all gone to their hometown for the lunar new year celebration. Nguyễn Dân rushed over to the hospital in Da Nang where Thị Thanh and Điền Cạnh were being treated. Thị Thanh’s condition was more severe. She had lost a lot of blood from her breasts and left arm, so much so that her left arm had to be severed through surgery at the hospital. Nguyễn Dân only got to see his daughter’s face through a window that night. She had a light blanket covering her. She turned and looked his way. When their eyes met, Thị Thanh asked in a barely audible voice, “What is going on?” That was the last of what she ever said.

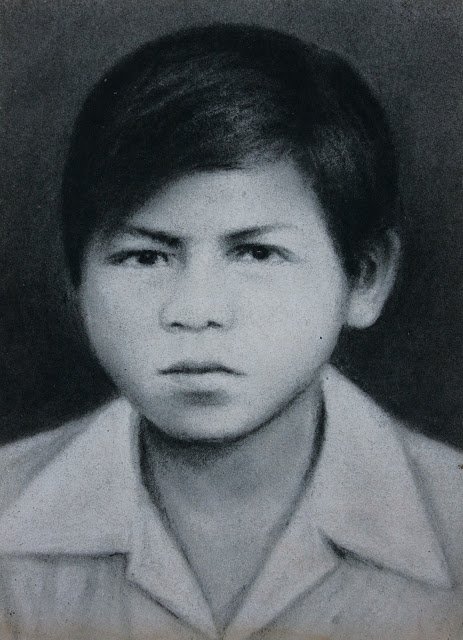

Nguyễn Thị Thanh died that day before the break of dawn. Three out of four family members passed away, and only Nguyễn Điền Cạnh made it alive, albeit with his buttocks severed (Nguyễn Điền Cạnh, lived as a disabled until he died at the age of 10).

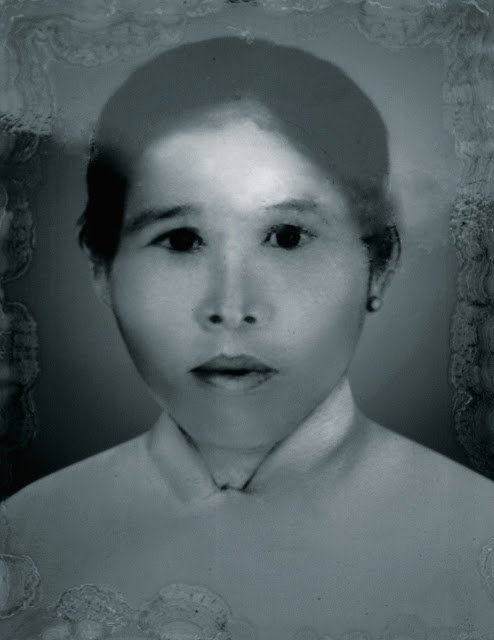

Nguyễn Thị Thanh, who had learned the trade of making clothing, her mother, Phạm Thị Cam, who passed away around the same time, and Nguyễn Điền Cạnh, who, after being severely injured when he was just five months old, passed away at the young age of ten. Trần Thị Thuận, who at age nine witnessed the final moments of Nguyễn Thị Thanh. Trần Thị Thuận passed away in 2008 from cancer. Photographs taken in April of 2001. (from above)

His wife, Phạm Thị Cam, along with their three children, headed for their hometown of Phong Nhất, two days before the lunar new year of January 28. Nguyễn Dân’s family had deemed Phong Nhất to be dangerous since the onset of war and therefore relocated to Da Nang, where they rented a place, with all nine of their children. Nguyễn Dân, being non-partisan, supported neither the South Vietnamese government nor the Viet Cong. But he knew that in such matters, only innocent civilians get hurt, which is why he had his family relocate to the bigger city of Da Nang. Only his elderly parents remained in their home in Phong Nhất .

Phạm Thị Cam was planning to come back right after the ancestral rites. The unexpected attack of the Viet Cong during the Tet Offensive and the counterattack operations by the R.O.K. troops kept her tied up in the villages. In Quang Nam Province, the Viet Cong took over Hoi An and were attacking the outskirts of the city as well. The 2nd Brigade 3rd Battalion of the R.O.K. Marines were dispatched to Hoi An, and the other brigades, including the 1st Brigade, were blocking of the outskirts of the city. The South Vietnamese government declared martial law. Even if Phạm Thị Cam tried to return home, there was no means of transportation she could take back. She had no choice but to stay in Phong Nhất until the day before the lunar new year festival, which is when she incurred her unfortunate fate.

Nguyễn Dân had insisted that they all stay away from their hometown, in spite of the lunar new year. He supported his family as a carpenter, and fortunately enough, he had a lot of backed up work. In fact, he needed a hand, so he had trained his second son, Nguyễn Điển Lộc, to be able to work with him. He regretted for the rest of his life for not having been able to convince his wife not to go back home for the ancestral rites during the lunar new year. Their daughter,Thị Thanh, had gone along to help her mother with the cleaning, and Thị Hường had followed along as well to help take care of their infant brother, Điền Cạnh. The two sisters followed their mother down the path of no return. Thankfully, the remaining five siblings stayed back.

Nguyễn Thị Ba(17) was one of the five who remained in Da Nang. She was the only one of the siblings who witnessed her sister Thị Thanh’s final moments at the hospital in Da Nang. With only two years’ age gap between them, the two shared the most intimate relationship among the siblings. Both dropped out of elementary school to help earn money in Da Nang. Thị Ba worked at a construction site, mixing cement. Thị Thanh made clothing to earn money. Thị Thanh had a portly figure and an easygoing personality. She acted as the eldest in the family after her older brother, Nguyễn Điển Đai, passed away from sickness. At the beginning of every year, she made clothes for her siblings to commemorate the new year. That year in 1968, Thị Thanh gave a handmade new year’s dress to Thị Ba. It was a sky blue dress with floral prints.

Nguyễn Thị Thanh's father Nguyễn Dân. In 2013. (Photograph by humank)

Nguyễn Thị Hoa(13) could not go to the hospital with his father and Thị Ba. She stayed at their home in Da Nang. Because she was young, she hardly did any work outside of household chores, nor did she attend school. She heard from her father that her mother and siblings died. The news of her older sister, Thị Thanh, instilled the most dread in her. Most people were shot to death, but Thị Thanh’s body had been stabbed. Thị Hoa shuddered at the thought of her older sister being mutilated at the hands of a Korean soldier.

Nguyễn Thị Thanh experienced unspeakable atrocities at the site of the massacre in Phong Nhất. Trần Thị Thuận(9), who made it alive despite being shot by the Korean troops, was the only surviving witness. Trần Thị Thuận was at the bottom of the pile of bodies shot by the troops. By the time Trần Thị Thuận regained consciousness, she could see Nguyễn Thị Thanh being taunted by the soldiers. She was able to register that Thị Thanh was being sexually abused. Her shirt had been torn. Thị Thuận could also make out the sword that the soldiers were holding. Everything took place right next to the home of Thị Thanh. It was right after the ravaging of Phong Nhị was over and the same was about to happen to Phong Nhất, so there were piles of corpses everywhere.

1) Nobody can quite explain why the 1st Squadron of the 1st Battalion of the 2nd Marine Brigade did what they did in Phong Nhị and Phong Nhất. It might have been the continued state of stress and fatigue that they were experiencing from the jungle operations in response to the Tet Offensive. Or perhaps it was the suppressed carnal desires of the young soldiers that caused them to cross the line when they saw a young female body. Whichever the case, it is hardly conceivable why they would go beyond mere sexual harassment and mutilate a woman’s breasts with a sword. Was it a high tactic trying to inflict extreme despair and shame on the men of the village, for failing to save their young women? Or had their intention been to instill enough fear of the ROK army to demoralize the Viet Cong? Perhaps sexual abuse is simply a matter of course during wartime, as it was for the punitive forces during the Jeju Uprising, the Japanese in Nanking, and the Germans in Poland during World War II.

As soon as the clock struck midnight in Gwangju, on May 18, 1980, martial law spread throughout the entire country. Airborne troops began their unapologetic beating and killing in front of the entrance of Gwangju’s Jeonnam University. Continuing from the 18th into the19th, the airborne troops brandished their clubs and swords at the citizens of Gwangju, who were filled with fury at the rumor that the troops stripped a female student and cut off her breasts in front of the fountain at Gwangju Station on the 19th. This would later be included in "Song of May," which commemorates the incident. "Your crimson blood, like petals, sprinkled on Geumnam street, your breasts cut off like tofu..." The atrocities committed by the troops were not reported to the press. Many of them were officers who had returned to Korea after their service in Vietnam.

More than twelve years ago, on January 31, 1968. Just as the clock struck midnight, martial law was proclaimed nationwide in South Vietnam. With the biggest yet counteroffensive being carried out by the South Korean, US and South Vietnamese alliance against North Vietnam and Vietcong, a 24-hour curfew order was issued in the capital of Saigon. The ROK military ran ruthless search and sweep operations in this area for more than a month. Particularly on February 12, rumors spread that the Korean troops stripped a young woman naked and killed her by cutting off her breasts in Phong Nhat. The rumor was true. US military intelligence agencies collected information on the atrocities of the Korean troops, but media access of the information was denied. Twelve years after the death of Nguyễn Thị Thanh, the Gwangju Uprising took place; and still two more decades would have to pass before her death would be first known to Koreans in 2000, a total of 32 years later.

(In reference to「On Sexual Abuse as a rite and Wartime Rape」(『Beyond Nationalism』Hasegawa Hiroko et al 1999) and「The female experience of National Abuse and the Jeju Uprising」(Kim, Sung-rae, 《Creation and Criticism》 December 1998)

1) I was able to hear the testimony of Trần Thị Thuận in April of 2001 in Phong Nhị. Thị Thuận, who was Nguyễn Thị Thanh’s close friend since they were young, was the sole witness of Nguyễn Thị Thanh’s last moments. When I visited Phong Nhị in January of 2013, I was no longer able to meet her again. The villagers informed me that she passed away from cancer in 2008.

- Written by humank (Journalist; Seoul, Korea)

- Translated and revised as necessary by April Kim (Tokyo, Japan)

The numbers in parentheses indicate the respective ages of the people at the time in 1968.

This series will be uploaded on Steemit biweekly on Monday.

Click to read in Korean( 1948년 제주, 1980년 광주, 그리고...)

Read the last article