Precursor to the Mỹ Lai Massacre: 1968 Phong Nhị, Phong Nhất_#6

Chapter 6: Appease Park Chung-hee

“Constructive!”

Reporters came rushing in to Yeong Bin Gwan, an accommodation for state guests, located in Jangchung dong, Jung gu, Seoul. A banquet that Prime Minister Jung Il-kwon (51) was overseeing was drawing to an end. A tall American man wearing a black double-breasted overcoat and a light brown hat was at the entrance, trying to make his way out of the banquet hall. Camera flashes went off. The reporters began asking questions all at once. The man stopped to answer a few of the questions before getting in the backseat of the car that was waiting for him outside. The only word that resonated with the reporters as they watched the car drive away was, “Constructive.”

It was the day that the Korean troops entered the villages of Phong Nhị and Phong Nhất—the very hour that the survivors were gathering the corpses of those who were less fortunate: February 12, 1968, 9:00 pm. In the figurative sense, a fire had also broken out at the banquet hall of Yeong Bin Gwan, where all the important politicians of Korea had gathered. The man had come to put out this fire, so he had to be prudent. After careful deliberation, “Constructive” was the best word he could think of, though it would be unclear exactly what he had meant by the word.

The man who had been stopped by the reporters went by the name of Cyrus Roberts Vance (51). He had arrived in Seoul two days ago as Johnson’s presidential envoy. It was a hectic day for Vance who had sat through over four hours of meetings with Korean personnel. At 9:15, he had a meeting with Minister of Foreign Affairs Choi Kyu-ha, at 9:30, with Prime Minister Jung Il-kwon, and at 10:00 with President Park Chung-hee at the Blue House. Everyone gathered for the meeting at the Blue House. Also present along with the aforementioned personnel were Kim Sung-un, Minister of National Defense, Kim Hyung-uk, Director of the Korean Central Intelligence Agency, and Lee Hoo-rak, Chief Secretary of the Blue House. From the U.S. side were William J. Porter, U.S. Ambassador to Korea, Charles Bonesteel, Commander of the U.N. Forces in Korea, and Waltz, Secretary of State. According to the press, the topic discussed by the personnel of both states was the ‘security assurance of Korea.’

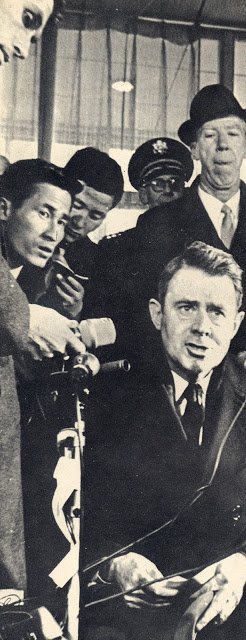

February 11, 1968, Presidential envoy Cyrus Vance is holding a press conference after arriving in Korea. He tried to meet with President Park Chung-hee that afternoon but was rejected because it was a Sunday. (Picture from the 1969 Press Picture Almanac).

They took a short break in the evening and reconvened for the banquet at Yeong Bin Gwan. A second round of high-level meetings was scheduled for the next day at 10:00 am with Prime Minister Jung Il-kwon. The questions that the reporters asked that day as Vance was exiting the banquet hall pertained to the meetings at the Blue House. Nobody knew what was discussed during these meetings. Vance could not give away the word that he was actually thinking in his head, “destructive.”

As a matter of fact, all throughout the meetings, Park Chung-hee kept making requests for destruction. According to a letter from Porter that was revealed later, Park suggested that they bombard the base of the North Korean Special Forces that attempted but failed to assassinate Park on January 21. He argued they at least have to give the North an ultimatum for a retaliatory attack should they act up again. From the U.S. perspective, however, this was not at all constructive. Vance accordingly refused to comply.

It was as expected. Park and the rest of the Korean personnel were extremely incensed. Vance was well aware of this even before he left for Korea on a U.S. air force plane from the John F. Kennedy Airport in the afternoon of February 10. Dong-A Ilbo portrayed him as “carrying the painkiller for the U.S.-ROK throes in his suitcase” (translated). As soon as he arrived at Gimpo Airport on the morning of February 11, he felt a chill colder than the freezing weather. Jin Pil-sik, Vice Minister of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Lee Beom-suk, Chief secretary for protocol in the Department of Foreign Affairs were at the airport. None of the ministers, let alone the president, came out to greet him. The Washington Post described this as a ‘cold shoulder’ treatment. Vance had hoped to visit the Blue House on the day of his arrival, but his request was denied on the Korean government’s basis that ‘there is hardly any matter pressing enough to warrant a visit with the head of state on a Sunday.’ Park instead spent the day practicing shooting with the First Lady, Yuk Young-soo, in the indoor shooting range in the Office of the Presidential Security, located in the basement of the Blue House.

Park Chung-hee found the entire situation absolutely absurd. He was beyond offended. On the night of January 21, 31 North Korean Special Forces attempted a raid at the Blue House, plotting to assassinate the president of a country. It was by far the most reckless act of hostility since the Korean War. On January 23, at about 1:45 pm, USS Pueblo, a U.S. Intelligence collection ship, was captured by four North Korean patrol boats and two MIGs in the coastal waters of Wonsan, Gangwon Do Province. The U.S. response to the two incidents were quite different. In contrast to the indifference it displayed when Park was almost assassinated, the U.S. acted as if it were ready to go to war when the USS Pueblo was captured. The U.S. dispatched the nuclear aircraft carrier, Enterprise, along with nuclear submarines to the East Sea, and relocated the the aviation corps with all its fighter planes from Okinawa, Japan to the air force bases in Gunsan, Jeonbuk and Osan, Gyeonggi Province.

Park Chung-hee met with U.S. Ambassador Porter, insisting with no avail that with regard to the security of South Korea, the trespassing of the North Korean commando unit should be considered a far greater threat than the USS Pueblo incident. The U.S. only took it a step further in the opposite direction and outright excluded South Korea from secret talks with North Korea regarding the resolution of the Pueblo incident.

That is how John V. Smith, Head of U.N. Military Armistice Commission, and his North Korean counterpart, Park Jung-guk, held their first meeting at Panmunjom on February 2. It was a meeting held in secret. Park’s pride was greatly hurt by the U.S nonchalance to the Blue House Raid, the inordinate amount of fuss it made over the Pueblo incident in contrast, and now secret Panmunjom meetings with the North. How dare the U.S. treat him this way after he had dispatched over 50,000 Korean troops to the Vietnam War? President Johnson wasn’t oblivious to Park’s anger either.

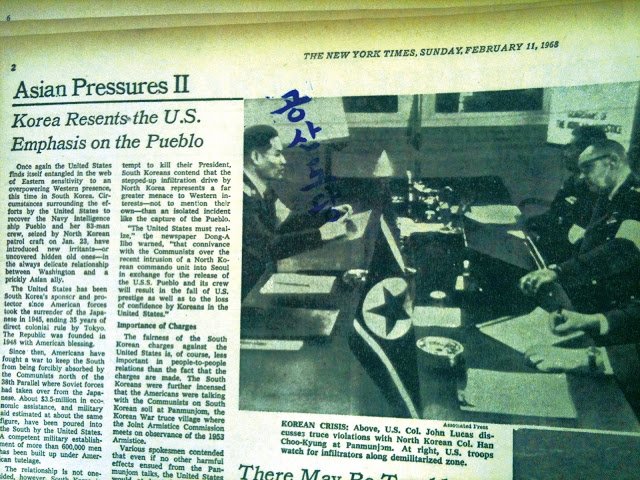

The New York Times, February 11, 1968. A photo of the U.N.-DPRK Military Armistice Commission Chief Secretary Conference in Panmunjom. It was publicly commissioned to address the raid by the armed communist guerrilla. Two hours before this conference, the fourth meeting between the U.S. and DPRK was held in secret to address the repatriation of the crew members of the USS Pueblo, which infuriated South Korea. The article addresses this anger. The picture from this article, which is kept at the National Assembly Library, there is a blue stamp next to the North Korean representative that says, “communist.” At the time, any foreign newspaper that had a photo of a communist politician, whether it be North Korean or North Vietnamese, was stamped with, “communist,” “North Korean puppet regime” or “puppet band.” (Photo by humank)

Vance was therefore selected to thaw relations between the two countries. He was a Yale Law School graduate. From 1961, he served under the Kennedy administration as advisor to the secretary of defense, secretary of the army, and undersecretary of defense. He exemplified great prowess as dispute mediator in 1967 when there was the Detroit Rebellion (12th Street Riot) and the Cyprus Crisis (between Greece and Turkey), therefore receiving great confidence from President Johnson as well. He looked extremely young for his age, “appearing to be in his rosy-cheeked 30s instead of in his 50s,” as the Korean newspapers would describe him. Moreover, he had a kind demeanor. Articles written on Vance were always well-disposed and sympathetic. Despite suffering from chronic spinal lesions, he sat through long meetings without a sign of discomfort. He only listened attentively to what the Korean personnel had to say. He always listened more than he spoke, as displayed during the December 13th National Assembly.

“You must be exhausted from traveling such a long distance,” greeted Lee Hyo-sang, chairman.

“I was able to sleep on the plane,” replied Vance.

No sooner had he said those words than the Korean personnel began accosting him, demanding to know why an emergency alert was issued for the Pueblo incident and not for the Blue House Raid, and how U.S. citizens would respond if Cuban armed forces were to raid the White House in a similar fashion (Kyunghyang Shinmun, Feb 14, 1968). Vance, who was completely caught off guard, was not able to respond.

Vance’s number one task was to prevent Park Chung-hee’s armed retaliation against the North. On February 2, about 10 days before his departure for Korea, Chief Secretary Lee Hoo-rak (44) informed Porter that the Korean government is in fact amply equipped with military plans. On February 6, Korean personnel called Vance and Bonesteel to the Capitol building and presented an ultimatum that “unless the U.S. takes satisfactory measures to address the issue at hand, Korea will carry out a certain grave measure of its own.” The next day on February 7th, the citizens of South Korea held a demonstration against the U.S. appeasement policy toward North Korea. The demonstrations eventually snowballed into an incident in which U.S. troops fired M16s at 300 students of the Gideon Seminary (Gumreung, Gyeongbuk) who were protesting in front of the Freedom Bridge of Imjin River.

To Johnson, the retaliatory attack that Park incessantly pushed for was falling into the trap set by the North. He was convinced that any misdemeanor performed by North Korea was actually an effort to remotely support their counterparts in Vietnam. The Pueblo incident and the Tet Offensive only further solidified his belief. Back home in the U.S., anti-war demonstrations and African-American civil rights movements were causing a commotion. Given this backdrop, Johnson had to dismantle the North Korean threat with caution. The lives of 83 Pueblo crew members were on the line. He couldn’t afford to flounder any longer in this quagmire, especially with the upcoming presidential election in November.

Johnson began trying to appease Park. He requested an additional 100 million dollars in military aid for Korea to Congress. The money was intended for aircrafts, anti-aircraft equipment, naval radars, patrol frigates, ammunition, and other military equipment for ROK defense. Johnson also sent a personally handwritten letter to Park through Ambassador Porter. The next day on the 9th, he decided to send Vance to Korea.

By February 13, when Vance attended the National Assembly meeting, Park Jun-gyu, Chairman of Foreign Affairs, who had accosted Vance at the airport regarding the exclusive emergency alert for the Pueblo incident, made a snide joke, saying, “We may appear like tigers, but we can be like doves, should we want to be.” Vance laughed it off cordially, replying, “I don’t know what being tiger-like is in the Korean sense, but you all seem like doves to me” (Kyunghyang Shinmun; February 14, 1968). Vance was careful to be diplomatic and constructive.

Vance was up all night on February 14 in his room at the Tower Hotel, Jung-gu, Seoul. Together with Choi Kyu-ha, Minister of Foreign Affairs, he drafted and redrafted a statement. Finally, on the morning of February 15, the U.S.-ROK Joint Statement was presented. Bold headlines along the lines of, “Immediate discussion when there’s a security threat,” “Pushing ahead with annual ministerial-level national defense conference,” and “Promoting modernization of the ROK Army,” covered the press. The word, “retaliation,” that Park Chung-hee so advocated did not make it on the joint statement. It was also reported that “classified documents detailing a firm U.S. commitment regarding ROK’s defense and supporting plans were exchanged along with agreed minutes” (Kyunghyang Shinmun; February 15, 1968, translated). Such documents were never exchanged, however. Vance had never agreed to such terms. Park, being conscientious of his reputation and the domestic press, fabricated the entire agreement.

It was now truly Park’s heyday. He certainly wasn’t able to achieve everything he wanted, but he could act as if he had the upper hand for once. He succeeded in making it seem like U.S.-ROK relations have never been better since dispatching troops to Vietnam in 1964. In order to secure two-thirds of the ruling party at the National Assembly election on June 8, 1967, Park largely rigged the election. He was able to meet the quorum for the passing of the third constitutional amendment. The U.S. remained silent. To Park, this was a grand opportunity.

Cyprus Vance, shaking hands with President Park Chung-hee before departing Korea. Photo from Kyunghyang Shinmun, February 15, Front page; with an article covering the U.S.-ROK Joint Statement for “immediate discussion when there’s a security threat.”

Vance returned to the United States in the afternoon of February 15 on a special plane after an eventful five days. He had told Park Jun-kyu that the Korean people were all like doves, but according to his report on the visit which was later revealed, Vance wrote something completely different. In fact, he reported that there aren’t many swans or hawks among the Korean populace, and that most people were “tiger-like.” To President Johnson, he even said, “Park Chung-hee has complete control of the country, and nobody says anything that he wouldn’t want to hear… Park is very emotional and whimsical, not to mention a heavy drinker… He is dangerous and volatile. Rumor has it that he hits the first lady and his advisors with an ashtray.”

The unfortunate truth was that the first lady and his advisors weren’t the only victims. South Korea was being remodeled in a weird way. From the autocratic viewpoint of Park Chung-hee, 1968 would be a very constructive year in which his aspirations would unfold.

written byhumank(journalist ; Seoul)Translated and revised as necessary byApril Kim(Tokyo)

The numbers in parentheses indicate the respective ages of the people at the time in 1968.

This series will be uploaded on Steemit biweekly on Monday.

Read the last article

Chapter 5: The Ruthless Marines

Chapter 4: Mean Streets of Saigon, and Loan, the Man of Power

Chapter 3: The Blue House Raid and Thuy Bo

Chapter 2: No ordinary gunshots

Chapter 1: Three Trivia Questions