Precursor to the Mỹ Lai Massacre: 1968 Phong Nhị, Phong Nhất_12

Chapter 12 : Massacre amidst a Lullaby

- Lê Đình Mận, who survived in the arms of his mother

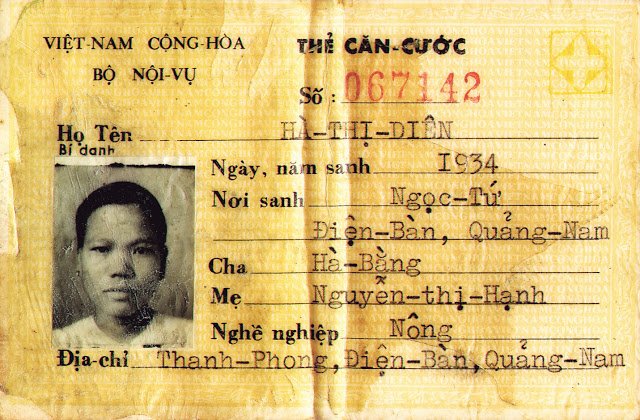

Hà Thị Diên’s citizenship card. Shot to death by Korean troops.

He was wrapped peacefully in the arms of his mother, feeding on her breast. He began dozing off, as she sang him a lullaby. Farmers were planting young rice seeds, a herd of water buffalo were passing by, and young pups were loitering about while wildcats hid among the ridges between the rice fields. His mother was waiting to finish breastfeeding him so that she could slowly begin working in the fields too. It was a typical pastoral scenery.

The serenity was broken by diabolic sounds of gunshots. His mother peered around with an ominous foreboding, but her infant was sound asleep by then. She held him more tightly, but he didn’t so much budge. She dashed in fear as the sounds of gunshots persisted, but the baby slept through the entire commotion, even when his mother was shot and fell to the ground. She hovered over her child, screaming. Yet the baby still remained asleep.

His mother lay prostrate until some time after, when some people discovered her and turned her corpse upright. Her shirt was still lifted up, her breasts showing. She silently passed away while feeding her child. She had taken the place of their father, overseeing all the farming and housework. She was a doting mother to her children, her three daughters, one of whom she lost early on, and her one son. Lê Đình Mận was her second son, whom she quite naturally coddled. Whenever she heard sounds of gunshots, she would hide in their bomb shelter in fear. She would hold her baby close, vowing to protect him at all costs. She went by the name of Hà Thị Diên. She was only 34 years old.

The people who turned her body upright found her baby snuggled under her corpse. He was stained with her blood, but he remained unscathed. Beads of sweat had gathered at his forehead as he remained sound asleep. He knew no sorrow. He could not yet distinguish between life and death, though the incident and ensuing fire in the village had taken the lives of his grandfather, mother and paternal aunt. He would awake from his naps and alternate between smiling and wailing. All he knew how to do was eat, sleep and poop. He was fortunate that his father, grandmother and siblings were still alive. Nobody knew what his name was, or how old he was, other than that he appeared to be about three months old, now that his mother had passed away. He was later given the name Lê Đình Mận.

Hà Thị Diên (below), after being shot to death while holding her baby, Lê Đình Mận. Her shirt is still rolled up and her breast revealed. The corpse above her is Nguyễn Thị Thời (from Chapter 11).

Their father worked in the South Vietnamese militia in order to provide for the family. He worked at a base that was 2 kilometers away from where they lived. In fact, he built a home next to the base for when he had overnight duties. He was lonely, but he needed to support his family with the consistent monthly pay he received. He had asked his older children to come sleep over at his home next to the base the night before the incident, which enabled them to escape from danger. When he saw his wife’s dead body, however, he cried out in agony. He couldn’t bear the sadness of knowing that his father and older sister had passed away as well. He was taken aback when the villagers brought and laid out the dead bodies in front of the militia base. They weren’t the only ones that lost family; He had lost his family too and was stricken with grief. He had been trying to protect them along with the U.S. troops. He nonetheless consoled himself, thanking God for at least protecting his infant son. Their father went by the name of Lê Đình Thức. He was 40 years old at the time.

Lê Đình Mận’s older brother grew up coddled by their mother. In fact, his brother was confident that out of the four siblings, he had received the most affection from her. He was ecstatic when their mother told them the night before to spend the night at their father’s. He spent the entire next day, goofing around at his father’s home near the base. He was displeased at the way his two younger sisters were behaving childishly. However, he didn’t seem at all bothered or fazed by the sound of gunshots the next morning. It was like any other day for him, as he was so used to hearing the sound. He figured it was just another tiff between the South Vietnamese troops and the Viet Cong. Only when the villages started blazing up in flames did he begin to realize that this was no ordinary day. Never, even in his wildest dreams, did he imagine his mother passing away, leaving behind his infant brother. Never did he have to grapple with the idea of death until seeing his dead mother, grandfather, and aunt. He felt a greater sense of duty and responsibility thereafter. He went by the name of Lê Đình Mực. He was only 10 years old at the time.

(February 12, 1968 in Phong Nhi)

I think about my mother often. Especially when my wife puts our children to sleep. My mother probably used to hold me until I fell asleep too. But this too is destiny. I don’t think hypothetically what it would have been like if my mother were alive. It’s not like it could ever become a reality. My brother says he remembers her face vividly, but I have no recollection of her. I was only an infant. The infant who was suckling her breast when she was shot to death by the foreign soldiers. If it weren’t for her love, I wouldn’t be here today. I made it alive miraculously because she held me and protected me to the end.

When I was younger, I used to dream of my mother often. She would be standing next to the door, wearing all white. She would stare at me in silence. The fortune teller interpreted this dream as my mother protecting me from above. I think that may be true. When I was two years old, I almost died from a severe ailment. Even three years ago, I fell unconscious while coming back home from a party on a rainy day. I must have eaten something wrong. Luckily the villagers found me and took me to the emergency room, but I was extremely close to dying. The fortune teller must have been correct. How old am I? I was born in the year 1967, in the year of the goat. I think I was born around November. On my identification card, however, I’m a year younger. It says I was born on November 28, 1968, haha. They must have hastily decided on a date. I don’t know my own birthday. I’ve never had a birthday celebration. But they say I used to be a mischievous little boy. Despite not having a mother, I grew up lighthearted.

Lê Đình Mận, standing in front of his home. January, 2013. Photography by humank

Four years after my mother passed away, in 1972, my father also passed away. My father used to be a South Vietnamese militiaman. He had been shot so many times by the Viet Cong, that it was nearly impossible to verify his corpse. We became orphans. Our relatives pitied us four siblings and said they would take one of us to each of their homes to raise us separately. My brother was vehemently against it. He insisted that we all be together. My brother has a strong sense of responsibility. He is 9 years older than me, but he did all kinds of work to support our siblings in the place of our parents. He was affectionate, and he enabled us to be able to fend for ourselves. Thanks to my brother, I was able to complete high school. He even sent me to work in a factory in the city. I wasn’t able to adjust and eventually came back to my hometown. I learned carpentry from my neighbors. I also farm for a living.

I met my wife through a friend. Her name is Ngô Thị Tùng, and she is three years younger than I am. We got married 18 years ago and had three children since. My eldest son, Lê Đình Minh Tiến, is 17 years old and in high school. My daughter, Lê Thị Ly, is 15 years old and in middle school. My cutest youngest daughter, Lê Thị Linh, is 7 years old and in elementary school. I always feel bad to my wife. I put her through a lot of hardships.

Up until two years ago, my wife worked at a manual labor factory for raincoats. Now she works at an industrial complex in Điện Ngọc, near Hoi An, at a shoe factory. She wakes up at 4:30am to do the laundry, make breakfast, and do the dishes before leaving for work at 6:30am. She gets off from work at 5:30pm, but works in the rice field for an hour thereafter before coming home. We do rice farming. I wake up around the same time that my wife does and help her with the housework before beginning my work at 6:00am. I plane and saw to make furniture. I also have to work in the rice fields. We also have three pigs that we are raising. My wife earns about 2,500,000 dong a month. I earn about 4,000,000 dong. We don’t have any outstanding concerns. Rice farming yields enough rice to eat for the entire year.

I’ve never been abroad. The farthest I’ve been is Vinh, which is below Hanoi. We just can’t afford to travel. Oddly enough, though, I’ve always been interested in international affairs. Especially areas where wars took place. I’m always curious to know how the troops kill people, and how the refugees receive aid from international organizations. The Iraq War doesn’t make sense. The U.S. said it will get rid of its terrorists but ended up torturing the Iraqi people. I just can’t fathom it. Peace is such a great thing; why do people choose war? I guess there’s always a reason, just like during the Vietnam War. The U.S. had something to gain from fighting in Vietnam. They started the war, despite that Vietnam didn’t want to get involved in war. They have a lot of money, so they were able to afford dispatching troops from other countries too. That’s how Korea got involved. The Korean troops dispatched to Vietnam were extremely inconsiderate and thoughtless. I mean, do they even have working consciences? We feel guilty over killing a chicken or a duck; How could they go about killing human beings like that? If it were during battle, if it were someone that was trying to attack them, then sure. But these were just regular civilians! What harm could a woman who was breastfeeding in the fields possible pose to them? Why slaughter her? What could have made them so upset? It was too cruel. They burned down houses--even the pigs, cows, and chickens. What did the cattle do wrong? I didn’t have to go to the army because both my parents passed away, and my own health condition wasn’t superb, but if I were a soldier, I may harm an opponent for my own survival, but I would never ever hurt the civilians or their livestock.

(January 22, 2013 in Phong Nhi)

Lê Đình Mận, who was but an infant sound asleep during the pandemonium of February 12, 1968, is as of January 2019, 52 years old. He still lives in his hometown of Phong Nhi in the Dien Banh District of Quang Nam Province, counting the small blessings he could share with his loved ones. This chapter is based on the interviews that I had with Lê Đình Mận and his brother, Lê Đình Mực, in January of 2003 and February of 2014.

Lê Đình Mận’s brother, Lê Đình Mực

Lê Đình Mực seemed to be delayed.

I visited his home in the afternoon of January 22, 2013. I called out his name, but nobody answered. Only their big pet dog barked ferociously. A little while later a small boy came out to say, “Daddy and mommy already went to work.” I waited in their living room for about an hour. Only long after it grew dark did I hear the sound of Lê Đình Mực’s bicycle.

“Please hold on a second,” Lê Đình Mực seemed discombobulated. He gathered the laundry that was hanging to dry, set the rice to cook and scampered around the house. I realized that an interview was a nuisance for him. After finishing up a couple of chores, he finally washed his hands and sat down, explaining, “It’s rice-planting season right now, so things are extremely hectic.”

Lê Đình Mận’s brother, Lê Đình Mực, speaks of his life after the incident. Photograph taken in January of 2013. Photography by humank

Lê Đình Mực is the brother of Lê Đình Mận, who was suckling their mother’s breast when she was killed in the massacre. That day, their grandfather, Lê Đình Dung, and aunt, Lê Thị Mỉa, also passed away with their mother. Their grandmother, Đoàn Thị Y, was severely injured. In 1972, when their father, who was a South Vietnamese militiaman, was shot to death by the Viet Cong, Lê Đình Mực, at the age of 14, had to take care of his three younger siblings. Their relatives offered to each take one child to raise, but Lê Đình Mực resisted. With a heightened sense of responsibility, he looked after his siblings on his own. He recalled “how difficult it was at first for him to make sure that his siblings weren’t starving.”

It might have been better if their father had died fighting as a Viet Cong. The fact that he was a South Vietnamese militiaman who was fighting against the Viet Cong, made Lê Đình Mực all the more ashamed upon liberation in 1975. The deep lines on his face seemed to attest to his many hardships. He was born in the year 1958 (his official resident registration read 1960), but in fact, he looked a lot older.

This was my second meeting with Lê Đình Mực. In April of 2001, when I came to Phong Nhi with a picture of a dead woman with her breast exposed, he confirmed that it was his mother with tears glistening in his eyes. He said that although it’s been a long time since his mother passed away, he could recognize her just by her hands alone. Lê Đình Mực reminded me that he wasn’t able to get back his mother’s citizenship card. I had borrowed his mother’s citizen card in order to publish a picture of it in a magazine article. Thereafter, I mailed back all the material that I had borrowed from the villagers, after scanning them, to the Dien People’s Council. I apologized and promised that I would print it and bring it to him the next time (which I actually did in 2014).

He lost his mother to the Korean troops, but he said he feels grateful to the civic groups that come to hear his testimony with contrite hearts. He carefully, yet frankly, expressed that he wishes the Korean people would offer more practical assistance. He spoke of the cemetery for the victims. “Each house paid for their own burial ground. The government didn’t assist at all. In our case, our mother’s grave is in the public cemetery near Hoi An. The graves of the less affluent are generally shabby and run down. Would it be possible for the Korean people to help out?”

Lê Đình Mực married Trần Thị Tào(1962~) in 1989 and gave birth to their daughters, Lê Thị Diễm and Lê Thị Hương, in 1990 and 1998, respectively. Their son, Lê Đình Thiện, was born in 2004. The age gap between their first and third children is 14 years. He admitted that he desperately wanted a son. I asked why it was so important to have a son, and he answered sheepishly, that “only a son would perform ancestral rites” for him when he passes away.

- Written by humank (Journalist; Seoul, Korea)

- Translated and revised as necessary by April Kim (Tokyo, Japan)

The numbers in parentheses indicate the respective ages of the people at the time in 1968.

This series will be uploaded on Steemit biweekly on Monday.