Precursor to the Mỹ Lai Massacre: 1968 Phong Nhị, Phong Nhất_#4

Chapter 4: Mean Streets of Saigon, and Loan, the Man of Power

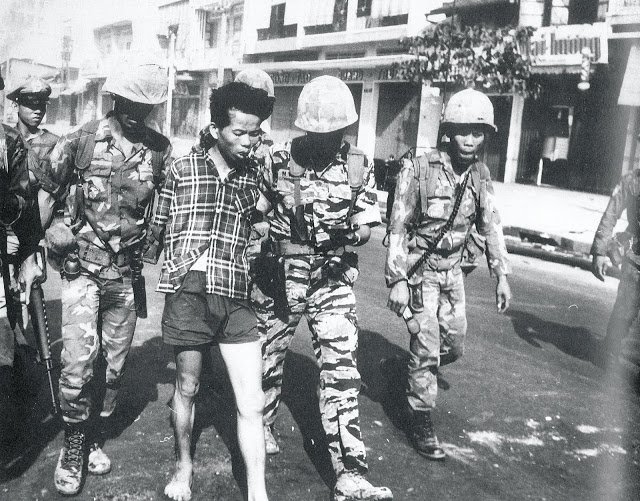

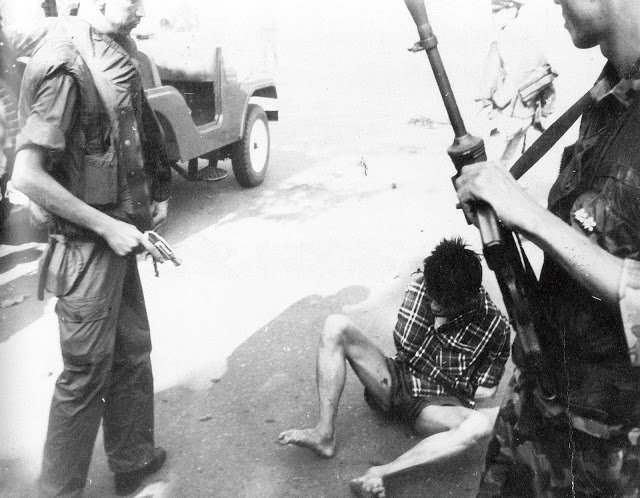

The man held his breath. The world seemed to come to a complete stop. He closed his eyes shut. He tried to move his wrists, but they wouldn’t budge. To his right, a soldier wearing military attire and an M1 helmet furrowed his brows as he stared intently at him. One could vaguely make out a military vehicle driving toward them from afar. Nguyen Ngoc Loan (38, hereafter “Loan”) pointed a 38-caliber revolver to the man’s forehead. Heart-pounding moments leading up to his pulling the trigger; photo taken by Associated Press reporter, Eddie Adams (35).

A clip filmed by NBC camera operator, Võ Sửu, is likewise ridden with suspense. The man, wrists tied back, is dragged in by several armed soldiers. Someone who appears to be an officer walks ahead and asks something. As soon as the man arrives, Loan pulls out a pistol from his chest. Without so much a moment’s hesitation, Loan points the gun to the side of the man’s head and pulls the trigger, and the man falls to the ground.

Both are coverages of the same scene from the infamous summary execution in the streets of Saigon (then capital of South Vietnam, and current-day Hồ Chí Minh). It was February 1, 1968, still in the aftermath of the Tet Offensive. The man who was shot is known to be the Vietcong officer, Nguyễn Văn Lém, but nobody knows for certain. Some say that his name was Le Cong na or Bảy Lốp. He was arrested for murdering the family of a South Vietnamese public official, but this too wasn’t for certain. He wasn’t even given so much an opportunity for interrogation. Loan did not ask; he just killed. There was no asking why.

Vietcong suspect with his hands tied behind him being pulled in by armed South Vietnamese soldiers. (Top) Right when General Nguyen Ngoc Loan is about to shoot the man in the forehead with a 38-caliber revolver; photographed by Eddie Adams of AP. Adams was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in 1969 for this photograph. (2nd from the top) Vietcong suspect fallen to the ground, lifeless. (3rd from the top) The blood flowing from his head spreading on the pavement. (Bottom) The three photographs besides those from the scene of the shooting, were taken by Kim Yong-taek, Korean photographer of Dong-a Ilbo (Photos from Kim Yong-taek’s News Photograph Collection: Moments in History, published 1995).

A day before on January 31, on the second day of the Lunar New Year celebration, fireworks colored the night sky of Saigon. Four days ago on January 27, the NVA and Viet Cong declared a 7-day ceasefire in observance of the holiday. There were many people who traveled to their hometowns (The Chinese, Koreans, and Vietnamese traditionally travel to their hometowns on the first day of the Lunar New Year). The new year festivities were further escalated by the fireworks. Yet, at random moments, the sound of fireworks was intermixed with the sound of detonations. Already, as of the day before, the Viet Cong had initiated a massive offensive in the entirety of Vietnam. Despite that it was already two days into the offensive, the citizens of Saigon were completely tuned out to the submachine guns and mortars being fired amidst the fireworks and furtively laying siege to their city.

The Viet Cong and NVA invaded Saigon, breaking their promise of ceasefire. In fact, they incorporated 80,000 men in both their regular army and guerrilla forces to incite their premeditated attack in all of South Vietnam. They resorted to hand-to-hand and street battles against the U.S., ROK, and South Vietnamese Armies after fiercely bombarding 7 provinces and 10 cities, including Saigon, where they even bombarded the presidential palace.

The most pressing moment was at 4:00 am on January, 31. A small commando unit of the Viet Cong shot a rocket launcher, broke into the the eight-story U.S. Embassy building in Saigon, and took over the first five stories for the next six hours. U.S. forces dispatched airborne troops to the rooftop of the building, and at around 10:10 am, after a bloody gunfight, the troops managed to kill the last of the 19 in the Viet Cong commando unit and retrieve the embassy. Eight Americans and nineteen U.S. marines lost their lives as a result. It was as if the commando unit had reenacted the raid that took place 10 days ago in Seoul, where the North Korean special forces managed to make their way all the way to the front of the Blue House.

February 1, Saigon .

Loan’s summary execution seemed to be a satisfying repayment, at least in the eyes of the citizens of Saigon who lost family members as a result of the Tet Offensive. They likely commended Loan for giving the commies what they deserve. But Loan was the director of security. Up until eight months ago, he was also the director of military security, putting him at the rank of brigadier general. His actions, as a high-ranking general of the South Vietnamese government, were impulsive, setting aside the legality of his decision to execute without trial. As mentioned above, AP and NBC were there to witness the scene. Kim Yong-taek (36), photojournalist of the Dong-a Ilbo, was also present. Kim couldn’t bear to keep his eyes open amid the brutality and could only take photographs after the men of the Viet Cong had already fallen. Loan didn’t seem to take heed to the presence of reporters and journalists, however. As a matter of fact, his execution was steady and confident. Indeed, there were few who were more audacious than he in all of South Vietnam.

It wasn’t until October 26, 1955 that the last emperor of Vietnam, Bảo Đại, was replaced, and the South Vietnamese government was officially established as the “Republic of South Vietnam.” The first president was Ngô Đình Diệm, who was referred to as the ‘Syngman Rhee of Vietnam.’ He was alienated by the public because of his persecution of Buddhists among other political corruptions, and was assassinated along with his brother, Ngô Đình Nhu, as a result of the coup d’etat that a group of young officers incited on November 1, 1963. The key figures of this coup d’etat were Dương Văn Minh, Nguyễn Văn Thiệu, Nguyễn Khánh, Nguyễn Cao Kỳ.

These figures appeared continuously throughout the many attempts at coup d’etat, including the more famous ones that took place on January 30, 1964 and on December 20, 1965. Eventually, Nguyễn Cao Kỳ rose to power as prime minister at age 35, and Nguyễn Văn Thiệu became the head of state, albeit nominal, at 42. However, two years later, on September 3, 1967, in the constituent assembly presidential election for the transfer to civilian rule, Nguyễn Văn Thiệu, and Nguyễn Cao Kỳ were elected as president and vice president, respectively. The two were lifelong political rivals. They decided, after much quarreling behind closed doors, that they would assume office in accordance to their ranks in the military. Loan was none other than the right hand and best friend of Vice President, Nguyễn Cao Kỳ.

Born in central Vietnam in the city of Huế on December 11, 1930, Loan graduated from Thủ Đức martial arts school and infantry school in 1952. He was a part of the France-Vietnam allied shock troops until 1953, when he left for the Air Force Academy in France, and later returned to Vietnam in 1955 to become its first ever bomber pilot. Throughout the early 1960s, he served as the second reconnaissance flight commander in Nha Trang, and in 1964, also became the deputy commander in chief to Nguyễn Cao Kỳ, who was commander of the air forces. Loan began rising to fame as he served as U.S.-South Vietnamese combined forces commander in a retaliatory bombing against North Vietnam after U.S. military lodgings in Quy Nhơn were bombed. He thereafter became a colonel and earned the title of director of security and director of military security.

Four years later, in the streets of Saigon, Loan appeared in the exact same uniform he was wearing when he shot the Viet Cong soldier eight days ago. In the photograph sent by AP, Loan is looking down from a balcony facing southern Saigon, which, after an intense battle with the Viet Cong, had fallen into ruin. The NVA and Viet Cong continued their attacks. The Viet Cong, who had taken over Chợ Lớn, a chinatown in the outskirts of Saigon, were advancing toward the center of town. The horse racetrack near the Tân Sơn Nhất Airport was also surrounded by flames due to the battles.

In the photograph, Loan appears lonely and deep in thought. The earlier photograph of him featuring the gruesome execution had been released in various parts of the world, and his life was in more danger than ever, now that he had become the main target of the Viet Cong. Loan wasn’t all that popular among the anti-communist youth of Saigon either, however. He had the most peculiar hobby of driving around town in his jeep along with his barber and shaving off the hairs of any youth that had long hair. He was notorious among the South Vietnamese government officials as well for causing a lot of headache.

Two years ago in October 12, 1966, seven South Vietnamese ministers from the department of health demanded through a collective resignation that Loan be replaced for abusing his power as national police chief. Loan was criticized for wielding his police power, as when he detained the chief secretary of the department of health without a warrant. From spring of that year, Loan, as Director of Military Security, was becoming increasingly infamous for his hardline policy against the Buddhist demonstrations in the central district. The demonstrations almost led to a full-blown rebellion because Nguyễn Chánh Thi had been removed from office. Although a political opponent of Nguyễn Cao Kỳ, Nguyễn Chánh Thi had been receiving avid support from the central district Buddhists. The demonstrations, which lasted for three months, emerged as the biggest internal disrupter in South Vietnam, occupying the political broadcasting station in Đà Nẵng and Huế, as well as leading to street battles.

General Nguyễn Bá Cao who succeeded Nguyễn Chánh Thi as commander of I Corps, was also removed from office for refusing to listen to Loan’s order of suppression. Eventually, it came to a point where Loan had to command the suppression himself, and General Nguyễn Chánh Thi sought political asylum in the U.S. Owing to this incident, however, Loan became the trusted right hand of Nguyễn Cao Kỳ and was promoted to brigadier general, his notoriousness increasing in similar fashion.

Loan managed to withstand that the ministers’ efforts to get him removed from office, but he eventually lost his position as director of military security in June of 1967 for being biased toward certain candidates in the presidential election. In November, he almost lost the position of director of security as well, but managed to hold on to that title, perhaps to everyone else’s detriment.

On February 13, 1968, his name started appearing in the press again. It was a press conference announcing that Trần Độ(45), holding the highest rank within the Viet Cong military political organization as Major General, was killed by a U.S. soldier in a street battle. Loan was asked to identify Trần Độ’s corpse. There were doubts raised on whether the corpse was indeed Trần Độ (the following day, it was actually reported that the corpse was missing). Some suspect that it was mere psychological warfare to demoralize the Viet Cong during the Tet Offensive.

Nevertheless, Loan ended up prevailing. In the one month that the Tet Offensive took place, the U.S. and South Vietnamese Armies each lost around 2000 men, but the Viet Cong and NVA lost nearly 10 times that number, suffering a casualty of nearly 300,000. The Viet Cong network in the southern region was completely destroyed. General Võ Nguyên Giáp, who led the Tet Offensive, planned to “use unprecedented warfare to launch a full-scale attack combined with a mass uprising,” but experienced crushing defeat (January 1968, Vietnam Working Party 14th Central Assembly). Ten days before laying siege on Saigon, Võ Nguyên Giáp incorporated two army divisions to pointedly attack Khe Sanh in the Quảng Trị Province, which was below the demilitarized zone and also where the U.S. Marine outpost was located. In order to counter this attack, the U.S. dispatched 75,000 troops along with B52s. Võ Nguyên Giáp’s plan was to hold up the enemy’s most elite troops in the northern region, and effectively attack the central and southern regions during the holidays. Yet the Tet Offensive was an utter military failure, which most likely left Loan, South Vietnam’s director of security, feeling elated.

Loan left a permanent impression on the Viet Cong. They had to somehow find a way to pay him back for the public humiliation and contempt he gave their comrades. The punishment had to be commensurate, if not outright a fatal blow. Three months later, in the very streets of Saigon, a Viet Cong submachine gun gave Loan a taste of his own medicine.

Loan, A Time for Punitive Justice

There are two more photographs of Nguyen Ngoc Loan that are not as well-known. The bloodthirsty Loan during the ‘Saigon Execution’ of February 1, 1968 is nowhere to be found in these photographs.

Koreans use the Chinese characters 因果應報 (Ingwa-eungbo) to convey that one reaps what one sows. If one commits wrong, one is bound to pay for it later, usually with some kind of misfortune. These two photographs clearly demonstrate this idea of karmic retribution.

February 9, 1968. General Nguyen Ngoc Loan (standing on the balcony of a building in Saigon-now Ho Chi Minh) looking down at the southern part of the city ruined by Vietcong attack. Pictured the next day on February 10, 1968 in the Kyunghyang Shinmun (South Korean newspaper).

The commencement of retribution. May 5, 1968. General Nguyen Ngoc Loan stumbling after being shot by a Vietcong submachine gun. Photograph by AP reporter; pictured the next day on May 6, 1968 in the Dong-a Ilbo (South Korean Newspaper).

A badge of honor in solitude. May 7, 1968, General Nguyen Ngoc Loan, receiving his badge of honor from President Nguyễn Văn Thiệu in his sickbed. Pictured the next day on May 8, 1968 in the Kyunghyang Shinmun (South Korean newspaper).

The first photograph is from May 5, 1968. An AP photographer captured Loan wobbling in the outskirts of Saigon. In the photograph, we could see Loan being propped up by Pat Burgess, a news correspondent from Australia, as he seeks refuge. Korean newspapers, Dong-a Ilbo and Kyunghyang Shinmun also made this their full-page lead story the next day.

May 5 is Buddha’s Birthday. Early dawn that day, the Viet Cong attacked 120 cities, including Saigon, and military facilities. As it was the largest since the Tet Offensive of January 30, it was called the ‘2nd Major Offensive.’ It was at a time when the Paris Peace Conference was being discussed between North Vietnam and the United States. President Johnson, to the shock of many, announced on March 31, 1968 through a televised special speech that he “shall not seek, and ...will not accept, the nomination of [his] party for another term as ... President.” With this, he also announced that the U.S. will stop the bombardment of North Vietnam, and suggested that Hanoi (North Vietnam) undertake peace negotiations with the U.S. Perhaps the Viet Cong were seeking to optimize both political and military pressure to secure an advantageous position at the negotiation table.

The Major Offensive of May 5 was weak compared to its January predecessor. Within 24 hours, the Viet Cong were driven back by the U.S. and South Vietnamese armies. They weren’t able to take over even a single city. Nevertheless, the allied forces did incur some significant damage as well. Forty people, including both troops and civilians lost their lives as a result. South Vietnamese Colonel Lưu Kim Cương (35) was one of them. He was hit by a B40 rocket-propelled grenade launcher while guarding the Tân Sơn Nhất Airport in Saigon. In Saigon’s chinatown, Chợ Lớn, three Australian reporters and one British reporter lost their lives to the Viet Cong while escaping the scene of the attack on a jeep. Hasso Freiherr Ruedt von Collenberg(36), the first secretary of the West German Embassy, was arrested by the Viet Cong in Chợ Lớn, where they tied his hands back, covered his eyes and shot him to death. Their main target, Nguyen Ngoc Loan, was dealt a severe blow but still managed to make it out alive.

The second photograph is from May 7. Loan is lying on his sickbed looking haggard. South Vietnamese President Nguyễn Văn Thiệu presents a badge of honor to him. Behind him is Vice President, Nguyễn Cao Kỳ, Loan’s godfather and Nguyễn Văn Thiệu’s bitter rival. Nobody knows the exact severity of Loan’s condition at the time. What information we have available, however, collectively indicates that one of his legs that was shot had to be amputated.

Thereupon he faded into obscurity. A month after Loan received the badge of honor, he left the position of director of security. That was on June 8. And since then, his name was never mentioned in the news again.

April 30, 1975, Saigon was taken over by the NVA, and as luck would have it, Loan ended up in America. On November 3, 1978, U.S. Immigration and Nationalization Services sent a notification denying him of his official residence permit on the basis of his immoral actions, but didn’t follow through in rescinding his green card. Thereafter, Loan moved to Virginia and ran a pizza parlour with his family until he was diagnosed with cancer. Loan was 68 years old when he died in his home near Washington D.C. on July 14, 1998.

Written by humank (Journalist; Seoul, Korea) Translated and revised as necessary by April Kim (New York, NY)

The numbers in parentheses indicate the respective ages of the people at the time in 1968.

This series will be uploaded on Steemit biweekly on Monday.

Read the last article

Chapter 3: The Blue House Raid and Thuy Bo

Chapter 2: No ordinary gunshots

Chapter 1: Three Trivia Questions