Reason and Emotion: The Children of Desire - Part IV

Source

Valentine's Day? To hell with your heart! As Stanislaw Lec said, it only wants your blood. Today let's work out that brain of yours and define some terms! Here's Part IV of my essay about Reason and Emotion - how they differ, and how they are related. If you're just arriving, I encourage you to read the earlier parts where I go through the history of some of the key concepts: Part I | Part II | Part III

Now that we know how history defines our terms, let's give them a flavor all our own:

As we have seen, reason is often used as the defining characteristic of man. As I have shown in the previous history, many philosophers equate the faculty of reason with the concept of Self. But in this essay, I will be arguing against such a thesis. While reason does seem to be one aspect of humanity that sets us apart from all other life on this planet, it is only a tool to be used, rather than the Self itself.

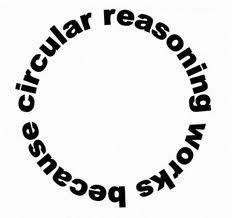

In order to illustrate this point, it is a good idea to examine the use of the word “reason” outside of its philosophical context. We use the word all the time, sometimes interchangeably with logic, objectivity, or understanding. But what do we mean when we say that someone is being rational? The American Heritage Dictionary defines reason as, “The capacity for rational thought... good judgment, sound sense.” Looking up the word “rational” we find: “Having or exercising good reason.” These definitions don't give much help, but the dictionary's circularity gives a hint at least to what reason is not. Reason does not include circular definitions.

Source

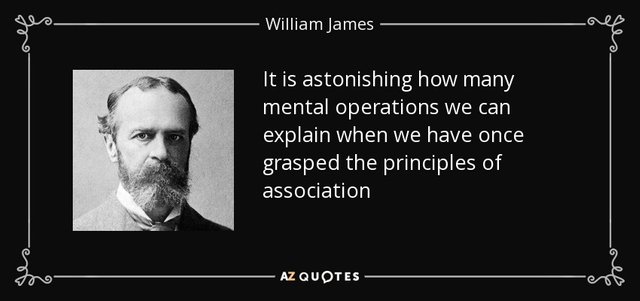

The word reason, however, can be used in a different context. Rather than describing a mental faculty or a categorization of thought, a “reason” can be a thought that propels one to a specific action, e.g., “What were her reasons for calling out of work?” A reason can also be a thing or event that causes some action in the world. An example of this could be, “The reason that the rock fell off the cliff was that it was pushed by the bear.” In other words, people use the word “reason” to describe a pre-existing condition that causes a later event. This sense of the word reveals one of the most important attributes of reason as a mental faculty: Reason is the recognition of cause and effect. It is the belief that if we witness an event A resulting in an event B, then, in the future when we perceive an event similar to event A, it will lead to an event similar to event B. William James, the late nineteenth-century American psychologist and philosopher, calls this association “contiguity”, and he describes it as one of two necessary attributes of reason.

While James believed that this association by contiguity is inferior to the second aspect of reason – association by similarity – I would argue that the latter is an extrapolation of the former. For James, man's ability to associate objects through similarity requires that he be able to break these objects into attributes, qualities, or essences. In doing so, a person may reassimilate those qualities under the heading of a concept, and he or she can later apply such concepts to like objects in the world. However, while the ability to associate through similarity seems to be more advanced than the ability to associate by contiguity, it is still a descendent of that former association. For, if one object has similar attributes to that of another object, one can assume that it will engage in like actions. By cause of similar attributes, similar actions and states will result. If such is the case – if association by similarity grew out of association by cause and effect – then this is evidence that reason is a faculty that has evolved over time.

Source

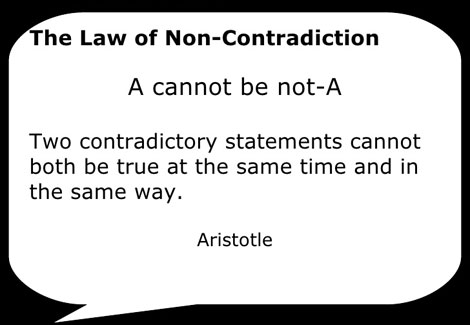

Two other important pieces that need to be added to this puzzle are the Laws of Identity and Non-Contradiction. The Law of Identity states: A is A. A thing is itself. This fact seems obvious, and it is obvious because people know it prior to experience. The Law of Identity is another example of Kant's a priori knowledge (though we first find it in Aristotle). The Law of Non-Contradiction states: A can have the attribute of B, or it can have the attribute of not-B, but it cannot have an attribute that is both B and not-B at the same time. The Law of Non-Contradiction bans the possibility of existing contradictions. It is not important to the present discussion whether we believe that these laws apply only to our faculty of thought, or whether they extend outward to objective existence. For, even if contradictions do exist in the world, our rational faculty makes it impossible for us to perceive them. Reason is that faculty of consciousness that helps to sort out the phenomena of existence, and reason will reject any possible evidence of contradiction.

Source

Therefore I define reason as follows: Reason is a mode of thought, developed over time, that relies on associations made by contiguity and similarity. Further, the faculty of reason bans the perception of contradiction out there in the world. This definition shows that reason cannot be considered to be interchangeable with the idea of Self. Reason is only one tool that the Self uses to perceive and interact with the world. Here we also begin to see that reason has its limits.

While reason is often cited as the defining characteristic of man, Trekkies know that reason without emotion only gets you a Vulcan.

Source

Emotions run from boiling, explosive anger, to sobbing, paralyzed sorrow, to cool, confident, and uplifting joy. It could be argued, as James does, that the number of different emotions are infinite and that our language limitations can only describe and discriminate a few of them. But what does it mean to be angry? It is more than a feeling of ill-will or violence directed at a particular person or object. Anger is a rise in blood pressure and perspiration. Anger is shallow breath. It is a stream of thought intoxicated with angriness. Emotion is a more complicated phenomenon than most people assume.

In order to simplify this phenomenon, I will break emotion into two parts: emotion-proper and feeling. Emotion-proper is the body's physiological response to a perceived object in the world. According to Antonio Damasio, a neurologist who specializes in the study of emotions, emotions-proper “are actions or movements, many of them public, visible to others as they occur in the face, in the voice, and in specific behaviors”. Therefore emotions-proper are the raised blood pressure and shallow breathing of anger. They are the physiological states of the body often not under the control of the person experiencing the emotion.

Source

Feelings, however, are the conscious experience of the emotions-proper. Both Damasio and another neurologist, V.S. Ramachandran, describe body-maps in the brain where sensory data from different parts of the body collect at specific locations. It is through these body-maps, Damasio believes, that a person is able to perceive his emotions-proper. It is this perception – one's perception of his body state through body-maps in his brain – that makes up one's feelings. This is the aspect of emotion that people most think of when trying to describe their anger or sadness. Taken together, emotions and feelings are behaviors and conscious states devoted to seeking a homeostasis in the body (Damasio). They are vital tools to keeping the living organism alive and well.

Emotions also have a great effect on our thoughts. As I stated earlier in this section, the feeling of anger always accompanies angry thoughts. Feelings are both a necessary ingredient for, and an outgrowth of, consciousness. These perceptions of internal body state – feelings – help to define for us a singular, united self. It is that self which thinks thoughts conducive to its environment and emotional state. Sartre describes emotions as a consciousness' ability to “transform the world”. By feeling anger, one changes his world, in that his opponent becomes an object to be reviled and attacked, whereas, before the feeling of anger, the opponent had no such qualities.

Source

This transformation of the phenomenal world is best exemplified in Aesop's fable of the fox and the grapes: A fox sees a ripe cluster of grapes practically bursting with sweet juice above his head. The fox, hungry, tries his best to reach the grapes, but his efforts do not achieve success. When the fox finally realizes the impossibility of his situation, he shrugs his shoulders and decides that the grapes are probably sour anyway. Thus the grapes, or the fox's perception of the grapes, have been transformed by a thought and an emotion.

In summation, I will be dividing the concept of emotion into two parts: emotion-proper and feeling. Emotions-proper are the physiological responses of the body to a perceived object. Feelings are the perceived emotional states of the body. Clearly, emotion is another faculty by which our Self reacts to, and sorts through, the world. Both feelings and emotions affect our thoughts and perceptions, and any choices we make will feel their influence.

Descartes' cogito, “I think, therefore I am,” is more than just a first principle of absolute certainty. It assumes the existence of consciousness. Not only am I aware of my self and my environment; I am conscious of my consciousness. But what is this thing we call consciousness? We can say that the flower of a plant “senses” the movement of the sun across the sky because its open bud follows that movement over the course of the day in order to absorb as much sunlight as possible. But very few people would say that the plant is conscious.

Source

While the flower senses, and reacts to, a certain part of its environment, it has no awareness of itself as a single, unified whole. At least there's no evidence to suggest that it does. What about your dog? He dashes across the yard to snatch up the ball you just threw; and he both wags his tail in animal joy when you reward him, and hangs his snout in shame when you scold him. Here we have a being who is aware of its environment and who reacts to that environment with outward emotional responses of “joy” and “shame”. But only the most hard-core dog lover would describe his pet as conscious in the same way that humans are conscious.

Before we go any further, we must distinguish between two ways of thinking about the term “consciousness”. The first way of thinking about consciousness is as awareness of one's surroundings. It seems rather simple, and one can almost apply it even to plants and animals. The flower is aware of its sun, and the dog is aware of its flying ball. Yet this idea of consciousness brings with it certain questions. If a man sits in a quiet room with a large grandfather clock tick-tocking to his rear, the sound of the clock will eventually fade from his “consciousness”. Any steady, droning sound will fade and fall off into the background. By this every-day definition then, the sound of the clock fades out of one's consciousness. Yet if that tick-tocking suddenly stops, the man will become aware of a strange new silence. Thus the sound of the clock had remained in his consciousness after all, but it slipped out of his awareness.

Source

Rather than come up with some complicated definition that can encompass both of these levels of consciousness, let us refer to this idea simply as perception. The man who first sits down in his rocking chair to read a much-loved novel perceives the ticking of his grandfather clock. As he rocks back and forth and is drawn into the story, the ticking fades from his consciousness but continues in his perception. When the clock stops, his environment is new and changed. This novelty thrusts the perception of the ticking clock – or the lack of that perception – back into the man's consciousness, and he sets the novel aside in frustration. The man gives the grandfather clock a faithful whack, and the ticking starts up again.

The second, and more difficult, idea of consciousness begins with the awareness of one boundary – that between Self and Other. The dog who barks in order to protect his territory is aware of its own body as well as that of the world and those encroaching bodies. Consciousness, despite rumors of gods and ghosts, must be bounded in a physical, finite body. There is a physical boundary beyond which a being's preservative actions and tendencies drop off. Yet to be conscious, as we are discussing consciousness, takes more than a simple line drawn in the sand. Within that finite boundary, there is also found a Self. An identity. A thinking thing. Even more important – there is a thinking thing that knows it is a thinking thing. True consciousness is to be aware of one's awareness.

Source

This awareness of consciousness – what Heidegger calls ontological knowledge – is exactly that which separates man from the flora and fauna of the world. One does not have to be a philosopher to have ontological thoughts. Even the most mediocre man occasionally steps back from direct perception of the world to an examination of himself and his own perception of it. Even watching a movie and empathizing with the hero is an example of ontological thought. It is the juxtaposition of one's Self and one's history with the events and history of another. But, though pet lovers will protest that their dog or cat has a distinct personality, there is no evidence to suggest that Spot is contemplating his position in the universe when he's off in the corner licking his testicles. We can only attempt to understand the conscious lives of humans because we ourselves are human, and because we use a meaningful mode of communication, language.

In order to have access to this ontological knowledge – in order to harness one's direct perceptions of the world and transform them into bundles of value and meaning – one must think of himself as a Self, and it is this that distinguishes a person from a flower, a dog, or a gorilla. A person must think of him- or herself as a discrete, continuous, and unified being with a history and a future. In human consciousness, the Self becomes an additional object in or of the world that can be observed, studied, and reflected on. While the faculty of memory is vital to its creation, one's Self is more than a sum of its parts. It is a structure or skeleton on which one assembles the pertinent memories and events of one's life, as well as the important beliefs and presumptions for the future. In Consciousness Explained, Daniel Dennett describes the self as “a web of words and deeds that, like the shell of a snail, protects the individual, and, like the web of a spider, provides one a living and a place in the world.” The Self is an ever-changing story whose plot and events shift and shuffle to meet the demands of the day.

The existence of these selves creates certain problems and puzzles. Where does this identity reside? What is it? Is it some special “stuff” or soul that the five normal senses we use to perceive the outside world cannot detect? Here again we are in the same position as the philosophers from above, and it is tempting to assert a mind-body dichotomy. Like astronomers watching a large mass of matter drawn inward to some invisible point who declare there to be a black hole, we observers of the self posit a “center of narrative gravity,” a dimensionless point out of which our thoughts, desires, and beliefs spring (Dennett). Yet there is no tiny homunculus residing deep within our brain taking notes and giving orders. There is no further command center within the command center of the brain to direct our thoughts and actions.

Source

In order to discredit this “Cartesian Theater” – a place in the brain where all sensory data is sent and studied, and out of which come all its orders and commands – a British neurosurgeon, Grey Walter, conducted an experiment in 1963. Subjects were told to view a series of pictures on a slide projector. Electrodes were implanted in the subjects' motor cortex, and they were told that they could advance to the next image at any time by pressing a button on a console. Unbeknownst to these patients, however, the console was not attached to the projector at all. The slide instead advanced when the electrode detected an increase of activity in the subject's motor cortex (the part of the brain which controls body movements, such as the wiggling of a finger). Since the brain and the nervous system are physical entities, and impulses in the nerves can travel at only a finite speed, the brain's command to press the button took longer to reach the subject's finger on the button than the electrode in the motor cortex. Thus the subjects thought the machine was reading their minds because the slide would advance a split second before they were aware of making the decision to change the image on the screen. This suggests that the brain is comprised of multiple systems and centers working simultaneously to achieve its ends, and it further suggests that consciousness has no precise center or hierarchy. The Self that we perceive within us is only a habitual tool we use to create order out of chaos.

Once again we return to the earlier way of thinking about consciousness. Just as the idea of oneself shifts and changes over time to meet the demands of the environment and the day, so too does one's immediate awareness. The senses are assailed every second by different sights, smells, and sounds. We perceive it all, but most of the data is thrown out immediately as being extraneous and unimportant. Other items, like the boring ticking of the clock in the earlier example, are collected and kept in a short-term cache of memory while still slipping under the radar of “consciousness”. What remains is that limited amount of perception which our present Self has access to. In this case, consciousness is an immediate, specialized faculty of perception that allows us to better interact with the world.

The second idea of consciousness is that which applies only to Homo sapiens (as far as we know). In this case, consciousness is an awareness of one's self, one's environment, and the defined boundary between the two. Even more important, it is the ability to observe one's Self as a seemingly seamless object, as an ever growing and changing story whose spinal plot-line shifts with the demands of one's will. Consciousness can alienate us from the outside world, yet it can strengthen and inspire by creating order and continuity as well as by defining a subjective viewpoint of values and desires. An existence without consciousness is unimaginable.

Source

I have tried to illustrate how and why our existence as conscious beings makes a mind-body dichotomy seem so satisfying. However, if we look beyond our own subjective experience and interaction with the world, I believe that we start to see that consciousness is a many-layered thing that springs directly from the brain, and therefore, the body. As technology advances, and more experiments like those done by Grey Walter above are performed, we will continue to get a clearer picture of what consciousness is, and the mind-body dichotomy will fade away. And with that, so too will the separation between emotion and reason.

I have defined consciousness as a faculty that directly perceives both the world and the self. But what is it about man that makes choices? Earlier I stated that both emotion and reason are simply tools, or ways of thinking, that influence our choices; and we can now see that consciousness also plays an important role in influencing our judgments and decisions. But what is the faculty that has the final say? What is it in me that chooses to walk down the street or eat a ham sandwich? How do I choose to steal or not to steal? To think or not to think?

Will, like reason, has often been used as the label to describe one's Self. But I have already suggested that the self is a fiction, and that it is nothing more than a habitual tool we use to create order out of chaos. If this is true, then one's Self does not make the final choices in life either.

Source

Will is the label I will use to describe that ultimate and underlying guide and cause to all our actions. Will, as I often think of it, is almost a non-concept. It is a summation of all past causes that have led to a particular moment for a particular individual; it is a product of both the genes that individual had at birth, as well as the experiences he's had in life; it is one's reaction to the present sensations of his environment, as well as to the emotions, feelings, thoughts, and desires of his consciousness and subconsciousness. Will is the unseen tyrant that propels all life.

Like Schopenhauer, one might be tempted to go a step further and describe inanimate matter too as having will, though it be “unconscious will”. Even the smooth, flat pebble on the beach rests on an unseen chain of previous causes that stretch back to infinity. The pebble's “will” keeps it there resting on the hot white sand. It “waits” for high tide when that chosen wave will unlodge and move it three feet down the shore. One can argue that the pebble has no knowledge of such a will, that it has no consciousness or awareness of it. But even conscious man is ignorant of the majority of the causes and reasons that make up his will. Even conscious, rational man reaches into that pack of cigarettes and lights that tobacco filled cylinder of paper when he knows it can lead to cancer, smelly fingers, and labored breathing. He can try to say why he reaches for that cigarette, but in the end he will only be able to answer: “I want it. I desire it.” The man has hardly any more knowledge of his will than the pebble on the beach.

Source

Even so, to say that inanimate matter has will would be to go too far. We would be stretching an already too thin concept into nothingness. But this juxtaposition of animate and inanimate will makes clear what this concept is not: Will is not solely conscious desire. Going back to our earlier example, people often describe the quitting smoker who rejects the offered cigarette as having strong “will-power”. she has made a conscious decision not to smoke based on her reasoned analysis that smoking is harmful, and because, by foregoing an immediate pleasure, she will likely reap greater pleasures in the future. But conscious reasoning is only a part of that faculty we call will. When conscious reasoning struggles against, and is victorious over, the unconscious influences of the body's desire for more nicotine and its deep ruts of habit, this is not an example of will-power but of reasoning power. Will, as the summation of all influences and causes of action, is victorious whether the woman smokes or quits.

Yet we are still left with the task of defining this concept, will. For if will encompasses and explains everything, it describes and contains nothing. We can start by calling it desire, and here I will define what it is I mean when I use that term. A desire is a hunger for value, and it can be either conscious or unconscious. Here too I must clarify and state that a value does not have to be conscious, nor does it have to be considered a concept. A value is simply some thing or action that an organism seeks to gain or keep or do. A desire is nothing more than the feeling of lacking value.

But what of conflicting desires? What about the apostate smoker who ever wakes to the struggle against being born-again? What of the child faced with that heart-rending choice between ice cream flavors: mint-chocolate chip or rocky road? If will is desire, and desires can war against each other, then we cannot think of will as a distinct, indivisible entity.

Source

It gets worse though. The examples from the last paragraph are conflicting conscious desires. What about those that are not conscious? Especially those unconscious desires that appear to be so appallingly irrational and self-destructive? Consider the woman who enters into abusive relationship after abusive relationship. She does not consciously wish to be beaten or verbally accosted. On meeting her latest beau, she does not see through his thin, charming demeanor to the pain-giving beast below. Yet throughout her whole life, the lovers she has chosen have turned into sadists. This is not a case of bad luck. Within her there is a subconscious desire looking for punishment, just as there is a subconscious desire in the men she meets to deliver that punishment; and somehow these shadowy wills perceive, choose, and greet each other. Yet on the surfac, she bewails her fate and shouts into her tear-drenched pillow that she did not want this, that she wants only a loving, caring boyfriend. And she is right. Part of her will does want that good healthy relationship. But another, stronger part wants the pain and suffering she always finds. How can the faculty of will be so fragmented?

Once again we are faced with a concept that has multiple levels of meaning. In every day conversation, the term will is predominantly used to describe conscious desires, thoughts and decisions that will lead to future action. The English language itself inherently promotes this definition. Our future tense necessitates it from the beginning: “I will eat lunch at twelve o'clock,” “I will go to bed early this evening,” “I will become the greatest football player who ever lived.” We look into the future and “will” that an event or action take place. “I will that it be so, and it will be so.” And often our later actions coincide with those previous statements of will. But too often they do not, and they do not because our will is more than a static, conscious claim.

Source

Will, as I will use it in this essay, is an ever-changing sum or mean of a multitude of struggling desires. Some of these desires are conscious, many are unconscious. These desires spring from an unknowable amount of causes – from genetic predisposition, to the body's seeking homeostasis, to true and false beliefs about the future, to remembered and misremembered events in the past, to the present perceptions of one's environment, to whimsy, boredom, and spite. Will defined in this way is not a faculty at all, but an ad hoc term chosen to describe that which is indescribable, to give a name to that which we can never understand. In this way, the term “will” is much like the term “God” – it is a meaningless concept that somehow still retains meaning. Will is the driving force behind life.

To illustrate this idea further I will use another metaphor. Will is a vast, shapeless blob made up of an almost infinite number of changing desires and causes. This blob surges up out of existence for a brief moment, and it uses consciousness, with the aid of reason and emotion, as its eyes and ears. But when this consciousness looks back at itself, it can see only that finite, united fiction we call Self. Consciousness can get only a partial glimpse of that vast and formless beast, Will, that carries, guides, and compels it. Finally, the Self lives its brief span, unwittingly making choices that the Will forces upon it, until it is once again swallowed up by the infinity of existence.

Okay - that's it for Part IV, and it was long. Kudos if you made it this far. More to come, and you can find Part V HERE.

If you found this post interesting and/or useful, I certainly appreciate all upvotes and follows. And I'd love to continue the conversation in the comments below. Thanks for reading

References

- Damasio, Antonio. (2003). Looking for Spinoza: Joy, Sorrow, and the Feeling Brain. New York: Harcourt, Inc.

- Dennett, Daniel. (1991). Consciousness Explained. Boston: Back Bay Books.

- James, William. (1890). The Principles of Psychology. New York: Dover Publications.

- Ramachandran, V.S., Blakeslee, Sandra. (1998). Phantoms in the Brain. New York: Quill Publications.

- Sartre, Jean-Paul. (1948). The Emotions: Outline of a Theory. Trans. Bernard Frechtman. New York: Citadel Press, 1976.

- Schopenhauer, Arthur. (1851). Essays and Aphorisms. Trans. R.J. Hollingdale. London: Penguin Books, 1970.

Nice piece..... Keep on d good work!

This post has received an upvote from spotlight thanks to: @resteemable.

I am @earnmoresteem and you got a 100.00% upvote courtesy of @jpgaltmiller! I invite you to send SBD with other post in memo and I will upvote you this new post.