Reason and Emotion: The Children of Desire - Part III

Source

Here's Part III of my essay about Reason and Emotion - how they differ, and how they are related. Here we continue with a historical examination of the concepts. It will be a pleasant stroll down a path that will touch on history, philosophy, psychology, and science. And if you missed it, you can start with Part I and Part II. Enjoy!

Immanuel Kant was a late-blooming flower of the Enlightenment who tried to reconcile the great warring ideas of his age: reason and religion. Kant lived through the philosophical turmoil of the eighteenth century: from the sensationalism and materialism of Locke and Hobbes, to the anti-materialism of Berkeley, to, most troubling of all, the skepticism of David Hume. On reading a German translation of Hume's works in 1775, the German professor was wakened from his “dogmatic slumber” and vowed to defend both the faithful precepts of religion and the foundations of rational science all in one blow. Six years later Kant had written his great opus, The Critique of Pure Reason.

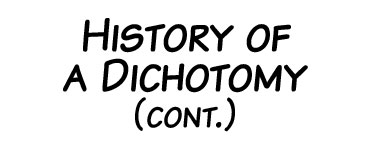

Critique in this sense holds no negative connotation, and the book is therefore an analysis of reason rather than a criticism; and when Kant writes “Pure Reason” he means reason and knowledge that exists a priori, or prior to the senses and experience. Like thinkers before him, Kant considers the rules of mathematics and other basic axioms of reason to fall under this heading, a priori; but Kant reaches beyond these previous philosophers when he describes the mind as perceiving the world through certain categories which shape and define its analysis of exterior objects. These categories – like space, time, and cause – cannot be escaped by the human mind, and they exist previous to one's experience. In fact, they define one's experience, and the fact of their existence necessarily divides the world into two distinct sets: phenomena and noumena.

Source

The word “phenomena” describes the objects in the world as they are perceived by human beings. Such a perception is necessarily incomplete because our categorical mind can only perceive certain, limited aspects of a thing. The word noumena is used to describe the objects in the world as they exist outside the scope of a perceiver. Noumena is existence as existence – the “thing in itself” – and we as subjects will never be able to gain any knowledge of it. We can never pierce through the mask of phenomena to the core of existence.

While Kant meant to construct these a priori categories as a permanent shield and grounding for science and reason, they instead deflate any aspirations we might once have had of gaining knowledge of absolute truth. It is only near the end of his 800-page treatise that Kant suggests limits to reason, but the brief suggestion is an inadvertent jab that threatens the coherence of all later philosophy. As an example, Kant argues that after we accept space as a category of the mind, the question of what lies beyond the Universe can have no meaning. If the Universe is bounded and limited, our mind cannot come to grips with the idea of nothingness lying beyond that boundary, for even nothing is something. Besides, if the Universe includes all of existence, and one of the facts of existence is space – how can space have a limit? How can space have a boundary? And yet if the opposite is true – if the Universe is infinite and unbounded – this too is beyond our comprehension (Durant). We cannot truly understand existence for what it is because the categories of the mind create an irrevocable opacity. And therefore, reason cannot bring us to full understanding and enlightenment.

Source

It is in Kant's second great work, The Critique of Practical Reason, where we find that other grouping of knowledge he labels a posteriori, or knowledge that comes after experience. And it is in this book that Kant discusses morality. Fearing the moral relativism that can result from skepticism, Kant declared a simple rule, the Categorical Imperative: “Act as if the maxim of our action were to become by our will a universal law of nature.” For the immediate moment, a lie may be the best action to achieve one's selfish ends; but a person cannot wish that all people everywhere always lie, for this would deprive communication of all meaning and it would make promises impossible. It is this categorical imperative which underlies our feelings of conscience, and it is practical reason that is the foundation of Kant's categorical imperative.

Source

For the German philosopher, the “good will” is that which acts from duty alone; and to act from duty is to act in obedience to one's reason. Here we start to see the complexity and difficulty of Kant's philosophy (and the limits to my own understanding of it), for he goes on to suggest that this “good will” can somehow reside outside the causal chain of existence that acts on all of physical nature. Kant is trying to extricate the foundering idea of free will from the determinism of the materialist philosophers with whom he is contending. In doing so he suggests that reason is a process that is also divorced from the causal chain of existence; and yet this would seem to contradict his earlier assertions that reason is limited by a priori categories of the mind. For Kant, the rational will is that which acts from an objective stance devoid of all selfish ends. It is therefore ironic that his philosophy would later be used as a springboard for so many subjective schools of thought.

In Kant, we see the last gasp of the Enlightenment. He is a man trying to reconcile science with religion. His Categorical Imperative is the Golden Rule buffed and shined with good-intentioned logic. At the same time, Kant is still trying to hold onto the idea of reason's perfectibility, and yet in his comprehensive analysis, he inadvertently delivers a devastating blow to reason's objective and neutral stance. The a priori categories of the mind prove to the world that reason can only act from a particular viewpoint – a limited, human viewpoint. But Kant still holds onto that age-old dichotomy between the reason of the mind and the emotions and desires of the body. Kant's will can bend either way, but the “good will” will always act from reason.

Source

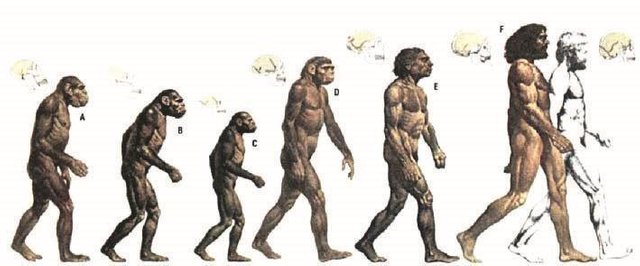

Much of the philosophy of the nineteenth and twentieth century could be considered a postscript to Kant, just as some historians think that all of Western philosophy is simply a postscript to Plato. While I could cite the importance of dozens of nineteenth century thinkers and intellectual movements to the present discussion, only one man and idea stand above the rest. That man is Charles Darwin, and his idea is evolution. While there were evolutionary thinkers before him (like Lamark), it was Darwin's idea of Natural Selection that made the idea of evolution feasible. Those characteristics of an individual in a particular species that are beneficial to that individual are passed down to his descendants precisely because they were beneficial. On the other hand, characteristics that hamper and hinder the individual will never make it to any descendants because such bad characteristics will likely prevent the organism from reaching maturity and bar it from reproducing . This does not mean that “only the fittest will survive”. A species does not have to be perfect to exist. It need only have characteristics that allow it to survive in its present environment long enough to reproduce.

Source

Darwinism shatters yet another artificial boundary: that between beast and man. With evolution we can see how fish were able to rise out of the water and walk the earth as amphibians; we can witness how dinosaurs changed over millenia to become birds; we can see how the tiny rhesus monkees grew into its larger cousin the gorilla . And if evolution can explain all this, why not evolving humans too? Evolution connects man back to nature, and, if animals are made up simply of body or matter, and if they have no access to spirit or mind, how is it that man could have access to any such thing? Darwin showed that human beings are not exceptions to the rule of Nature. Any characteristics or faculties we have are ultimately descended from the first one-celled organism.

Source

In the twentieth century some of the most interesting discussion about reason, emotion, and the mind condensed itself into a new subject altogether: psychology.

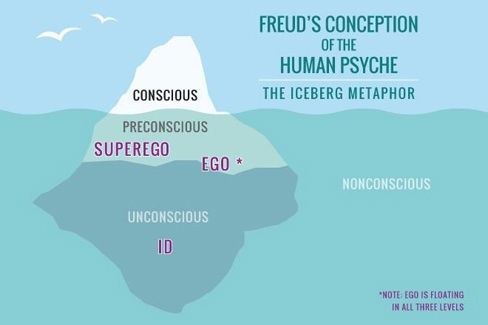

Sigmund Freud was one of psychology's earliest pioneers. He, like Plato before him, describes a tripartite soul when he divides the mind in three: Id, Ego, and Superego. While Freud's and Plato's internally warring soul are not exactly the same, there is a strong resemblance between the Id's tumultuous storm of unconscious desires and Plato's animalistic appetite. The Ego, similar to Plato's reason, ideally runs the show in Freud's view, and his Superego becomes a sum of all emotional values collected from the perception of one's parents, siblings, and environment in general. Once again we see desire, emotion, and reason divided. Unlike Plato, however, Freud does not believe that reason can retain unthrowable reigns. In Plato's metaphor of the charioteer, reason is powerful and in command. Appetite is an unruly horse, but for Plato only a weak mind cannot keep it in check with the reigns and whip of reason. Freud's Ego, on the other hand, is a meager referee who tries to reconcile the vast unconscious desire of the Id, with the irrational and tyrannical morality of the Superego. For Freud, the Id is too often a giant beast that carries the Ego atop its shoulders. The Id uses the Ego's rational faculty to achieve its own ends, and this is true of all minds, great and small, weak and strong.

Source

While Freud diminishes the powers of reason and emotion, and sets them as inferior to desire, the behaviorist school of psychology tries to extinguish all three. B.F. Skinner, the school's most infamous proponent, believed that it is only one's actions or behaviors that can be known and classified. Therefore, to look into the mind for emotion and thought is both impossible and silly. If we are to understand ourselves, by the behaviorists' judgment, we must look solely to our actions divorced from any perceived internal cause.

While the behaviorists' attempt to bring human behavior and cognition under the blanket of purely physical causes is one which I applaud, it is clear that they go too far. Skinner tries to destroy the dichotomy between mind and body by simply refusing to recognize the phenomena we all experience as mind.

Source

But if one wishes to create a viable alternative to this dichotomy, he must account for these things rather than bury his head in the sand of denial. Thoughts and emotions are perceived by all people within themselves. As technology has advanced, so has our ability to observe these internal actions that the behaviorists once rejected. It is now believed by the cognitive-behavioral school that thoughts and emotions are actions in the same way as running and jumping, and that, if they cannot be fully understood now, then they may one day be explicated in the future with the use of more advanced technology. The neurological discoveries of the past fifty years are what allow us to see beyond the old dichotomies between body and mind, and reason and emotion.

Source

This is where history has led us, and I will now define these basic terms that I have been throwing around so loosely. Understand that these will be my own definitions, and that their truth will be limited by my finite research and reading. Do not be surprised if the following definitions run contrary to how thinkers in the past have thought of them.

Okay - that's it for Part III. This will be broken down into several parts, and you can find Part IV HERE.

If you found this post interesting and/or useful, I certainly appreciate all upvotes and follows. And I'd love to continue the conversation in the comments below. Thanks for reading

References

- Darwin, Charles. (19th century). On the Origin of Species. New York: Penguin Classics.

- Durant, Will. (1991). The Story of Philosophy. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- Freud, Sigmund. (1923). The Ego and the Id. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

- Kant, Immanuel. (18th century). The Critique of Pure Reason. New York: Penguin Classics.

- Kant, Immanuel. (18th century). The Critique of Practical Reason. New York: Penguin Classics.

- Skinner, BF. (1974). About Behaviorism. New York: Vintage.

Really like this, a great analysis, and your memes are so on point. I am really attracted to Kant's thinking, but have not yet had the courage to read any of his works directly.

Still, the categorical imperative is damn interesting, and I agree that skepticism was/is a danger to morality.

I'll admit, I've never read unadulterated Kant (more than a few pages at a time). But I'm definitely no Kantian (though his categories, and how/what the brain is able to perceive must therefore affect what we perceive, and/or filter the world, is a significant achievement).

And actually, I think I missed your last point: I definitely do NOT agree that skepticism is a danger to morality. :) (Part of the confusion here may be that I'm trying to detail the historical background, laying the foundation for what I actually think. Still coming.)

Nice! I'll look forward to hearing your argument for skepticism then!

Part of this may turn on how you define skepticism. There is a philosophical school of thought that just plain refuses to believe anything. That's not the kind of skepticism I'm talking about. Skepticism, for me, is the refusal to believe anything on faith - or at least an attempt to bring the faith quotient way the hell down.

Said another way, skepticism should not be a stance, but a tool to discover truth. That being said, truth is not possible without skepticism; and morality is not possible without truth.

Congratulations! This post has been upvoted from the communal account, @minnowsupport, by jpgaltmiller from the Minnow Support Project. It's a witness project run by aggroed, ausbitbank, teamsteem, theprophet0, someguy123, neoxian, followbtcnews, and netuoso. The goal is to help Steemit grow by supporting Minnows. Please find us at the Peace, Abundance, and Liberty Network (PALnet) Discord Channel. It's a completely public and open space to all members of the Steemit community who voluntarily choose to be there.

If you would like to delegate to the Minnow Support Project you can do so by clicking on the following links: 50SP, 100SP, 250SP, 500SP, 1000SP, 5000SP.

Be sure to leave at least 50SP undelegated on your account.

Your Post Has Been Featured on @Resteemable!

Feature any Steemit post using resteemit.com!

How It Works:

1. Take Any Steemit URL

2. Erase

https://3. Type

reGet Featured Instantly � Featured Posts are voted every 2.4hrs

Join the Curation Team Here | Vote Resteemable for Witness