The Romance of the Sword

In the age of the gun, the romance of the sword lingers in pop culture. From wuxia novels to martial arts flicks, heroic fantasy tales and stories of sword and sorcery, people enjoy stories of blademasters cleaving their way through hordes of enemies.

On first glance, this seems strange. These stories hardly have any bearing on modern life. In a world where war is fought with button presses and trigger pulls from long range, how relevant are stories of men who throw themselves into a storm of steel? Likewise, they don't necessarily educate the current generation of how their forebears might have lived; authentic they may be, but there is no substitute for scholarly research. Even if these stories reflected the reality of the lives of hard men of a hard age, it is an experience utterly alien to lived experience today.

Yet, because of this alienness, the romance of the sword is very much relevant today.

In the pre-gunpowder era, war was fought up close, at arm's length or closer. Men prevailed through skill, courage, and raw muscle. Combat was a personal affair, so close you could smell the enemy's breath, taste his fear, feel his lifeblood ebb on your blade--or yours on his.

Lt. Col. Dave Grossman's On Killing posits that the closer a soldier is to the act of killing, the greater the psychological trauma he endures. A World War Two bomber pilot can sleep peacefully in his bed after killing hundreds from the air with incendiaries; an infantryman who bayonets his enemy in the heat of battle may never sleep well again. Combat in the age of the bullet is a far cry than war in the age of the bullet, paradoxically less destructive and far more ferocious at the level of the individual.

Yet despite the cost of killing at close range, history lauds famous warriors who spent their lifetimes at war. The conquistador Francisco Pizzaro, the man who conquered the Incas, who at the age of 70 faced an assassination attempt by 10 men, and slew 3 before succumbing to his wounds. William Marshal, 1st Earl of Pembroke, renowned for his personal courage and skill at arms, who claimed to have defeated 500 knights in various tournaments throughout his life. Miyamoto Musashi, who claimed to have fought 60 duels and never lost.

In the days before massed firepower dominated the battlefield, it was not inconceivable for such apex killers to have slain scores, even hundreds, of opponents by their own hand. And they did so at melee range, without the benefit of modern armor or armaments. In such a deadly environment, how can a man survive -- even thrive?

For starters, he must be strong and healthy, ideally with an excellent immune system. He would have been exposed to filth and hazards that modern society deems intolerable, and he would have to win his battles not with a simple finger press but with the power of his entire body. In this unforgiving age, an age without penicillin or modern medicine, strength is power and health is all. The weak succumb, and the strong take what they will.

He must possess courage and cunning in abundance. Courage is obvious: when a man charges at you intending to take your head off, it takes courage to step into the arc of his swing to deliver the counter-cut. But cunning is also necessary, arguably even more so. The bravo who walks up to his enemies demanding a fair fight would be quickly stabbed in the back by a blade he didn't see. Honor and chivalry were ideals, not reality. The grim reality of war, pre-modern and today, is that you must strive to end combat quickly and efficiently, lest the enemy find a chance to counterattack -- and kill you. Thus, the apex warrior must be well-versed in the art of strategy and deception, to gain a decisive advantage over his foes without allowing them to outwit him.

To achieve mastery of the blade, the warrior must be disciplined. He must be devoted to the art of weapons and war, rigorously practicing it without cease for years and decades on end. Without such single-minded focus, he will surely fall to a foe who put in more time and effort practicing the trade. Not only that, he must discipline his heart and mind, to never allow fear of death to creep into his soul, lest he make a fatal mistake.

He who achieves the acme of skill also gains the greatest quality of all: insight. Throughout his life, he would have seen the difference between men and women, the weak and the strong, the rich and the poor, the craven and the chivalrous, and thus knows the nature of humans. To grasp battlefield strategy, he must develop an understanding in human psychology, geography, physics, space, time, and where they intersect. To see through the stratagems of his foes, step into the blade and cut down the enemy without being cut, he must cultivate a calm heart and unclouded vision.

Classical Japanese martial arts teach that the way of the sword is the way of strategy, and that he who practices the way of the sword also walks the long road to enlightenment. He who masters the sword becomes the master of himself, and in so doing becomes the master of all.

To go back to the original question, the romance of the sword lies in the romance of the swordsman. He is the embodiment of the idealized man, the warrior and conqueror par excellence.

From the West, immortal figures like Conan the Cimmerian, Solomon Kane and John Carter of Mars display the Western heroic ideal of the swordsman. He is usually a noble savage, apparently primitive in his ways, yet more honorable than men of the city. He is loyal to his friends, merciful to those in need, yet relentless in war. He is a specimen of Olympian vitality, strength and endurance.

Eastern swordsmen are paragons of skill and virtue. The youxia of Chinese wuxia fiction are celebrated for their mastery of arms, live in a milieu that holds personal honour and morality in high regard, simultaneously upholding the tenants of civilization while living apart from it. Xianxia stories take things one step further, with heroes and villains alike striving to cultivate their personal qi, eventually gaining the powers of gods. Warriors from Japanese jidaigeki are compelled to live by the strictures of a rigid class-bound society or thumb their nose at it. Martial valor is held in high regard, and warriors are at the head of the pack. More esoteric fiction would even follow the warrior's quest for enlightenment through the blade, such as the award-winning manga Vagabond.

The appeal of the swordsman lasts through the ages because he embodies many masculine virtues. Strength, skill-at-arms, valor and virtue combine to create an unparalleled warrior; with insight and faith, he ascends to the role of warrior-priest. He represents the archetype of the hero, one of his countless reflections across the ages.

He is a hard man of a hard age -- and in this era of softness and comfort, he is an ideal even the common man can aspire to.

(image from Pixabay)

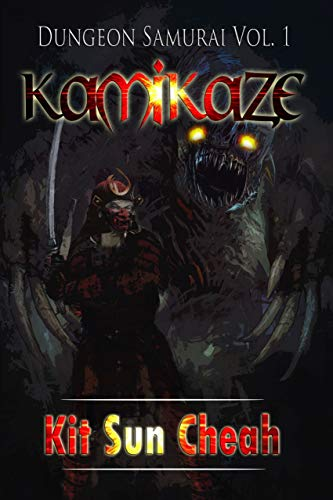

When ordinary college student Yamada Yuuki is transported to a death world teeming with monsters, his only hope is to practice the way of the warrior. Follow him on his grim campaign through a bloodsoaked dungeon in the DUNGEON SAMURAI trilogy!

To stay updated on my latest news and promotions, sign up for my mailing list here!

Thing is, the sword was not the standard battlefield weapon in most cultures. Whether we are discussing European knights, Japanese samurai, or any other historical pre-gunpowder culture, the infantry weapons of choice were spears or various polearms.

I think the real allure of the sword is rooted in a few factors:

A sword was the preferred backup sidearm of the soldier and the civilian's best weapon for self-defence. This is like the modern pistol, and distinct from daggers and other knives even though various smaller blades are common weapons throughout history.

Legendary swords of myth and legend lend an aura of supernatural power to the idea of the sword. See the list of historical and legendary swords and the list of fictional swords at Wikipedia.

The spectacle of the duel on stage and screen also maintains the aura of the blade in pop culture. My name is Inigo Montoya. You killed my father. Prepare to die.

These are fair points. To add on:

Swords were fairly common weapons. Polearms were preferred battlefield weapons, but swords were convenient to wear for daily life. In Japan, only the warrior class had the right to wear two swords -- and later, they were the only ones allowed to go armed at all. Their prevalence ingrained them in popular consciousness.

Despite their commonality, mastering the sword still requires immense dedication. Skill in swordsmanship reflects a great investment of time, energy and resources, as well as discipline and mindset.

Legendary weapons do lend a supernatural air to the sword. On the other hand, in at least some cases, the wielders had to earn the right to carry the sword -- or the sword itself was a reflection of the man. By pulling the Excalibur from the stone, Arthur signified that he was the rightful king of England. Other swords in the link you put up gained honour and fame because they were wielded by famous people, and were associated with great deeds or myth.

The staged duel certainly makes for a visual spectacle. And that alone can explain a long-standing interest in swords in visual media. But it takes skilled wielders to make the duel look interesting.

The thrust of this article is to go beyond mere spectacle and visual appearances, and deep into the realm of myth and archetype. The sword in itself has no will of its own, only that of the hand that wills it. And the swordsman reflects the archetypal masculine conqueror across the ages.

I'm not entirely sure it represents conquest. Not entirely, anyway. We have phrases like "put to the sword" as a euphemism for slaughtering civilians. However, the fact that the sword and großes messer were widely used for self-defense and duelling seems to me the great distinction between the sword and other more common weapons of war. I would prefer a naginata over a katana in combat in Japan, but I would also want a katana or wakizashi as a backup. Similarly, I would want a spear or poleaxe in medieval Europe, but a longsword or arming sword would be a convenient support option. In this respect, I think the sword is analogous to the pistol. Rifles and shotguns win wars and protect pioneers, but the pistol as a backup weapon and a means of civilian self-defense reigns supreme in the public consciousness. But while pistols often signify an officer in the military, though, they haven't replaced swords as a ceremonial emblem. And while pistols are very much another weapon requiring training and expertise to use well, the allure of the sword supersedes it. The mythologized history of the medieval era probably plays a major role, but there remains something individualistic about the sidearm, and that essence is I think the key.

To listen to the audio version of this article click on the play image.

Brought to you by @tts. If you find it useful please consider upvoting this reply.

@cheah Simply amazing! Resteemed!

Posted using Partiko Android

This post was shared in the Curation Collective Discord community for curators, and upvoted and resteemed by the @c-squared community account after manual review.

@c-squared runs a community witness. Please consider using one of your witness votes on us here