Playing in the Garden: Setting Archetypes Part 1

I've written about archetypal settings in the past, but I feel like it's time to start talking about how the use of archetypes in settings can really shape how we play games.

Archetypal settings have a strong relationship with plot development, and they're important to game designers and narrative creators because of the fact that they are, unlike characters, a place where the writer can have total control over the world. With characters–or at least the player character–there are a lot of things that can and should change as a story develops. How others react to them and how their plans succeed or fail all interact with their motives and needs, and that makes them very complicated.

In any interactive media, that's nearly impossible to pin down. In something like a tabletop roleplaying game, you're going to have a hard time doing this at a level that works for everyone; even if players let you dictate a lot about their characters (spoiler: they won't), you can't necessarily guarantee that any number of characters will go through a Hero's Journey simultaneously and as a result you can't really plan around that.

In something like a roleplaying game, you may even find players who don't seek to be a hero in the traditional sense, which is another place where character-driven storytelling can have issues. As a result, the characters that you create have to play either a pivotal role or a side-role depending on what the players do.

And this is a place where you can very easily run into major issues. I remember a few instances in gaming where a character would drive the plot when they didn't really have a right or reason to (EA's Syndicate reboot where the protagonist was awoken by another character and turned against his own corporation, with no input from the player, stands out as particularly egregious).

Since in interactive media you are relying on the player to drive, or at least follow, the plot, rather than have it change around them, you can't rely on many of the devices that can be used sparingly in other forms of writing.

This is where the setting archetypes come in so handy. They're not a bad tool for all storytellers; indeed, I personally think that they have some of the greatest potential to be visualized and apply outside of their stories; pretty much anything by Tolkien capitalizes on this heavily; the Shire, Mordor, Gondor, the Elven forests and shipyards, and countless other places in Tolkien's Middle Earth all manage to perfectly evoke these setting archetypes.

By focusing on telling stories using the setting, you allow the audience to fill in with characters of their own, something that is especially important in a roleplaying game with multiple players: each character can fulfill the role that the player and the group dynamic would lead them to take, without resulting in issues with determining which character is going to take the narrative spotlight at any given moment.

Another place where the setting archetypes work well and character archetypes tend to fall apart is when you need to evoke some urgent moment or plot point, and your characters are at a point that would suggest otherwise. For instance, the climactic battle scene of Thor: Ragnarok is also an example of the Fall of Eden, something that occurs in a setting that would be much more common at the start of a story.

Becoming familiar with these archetypes gives the storyteller another set of tools, and I'll be giving examples of the archetypal settings that I use in the chronological order that I introduce them in my stories.

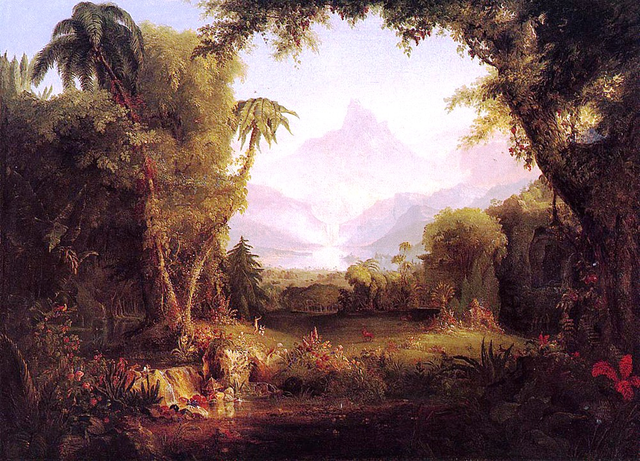

What is the Garden?

The Garden is none other than the Garden of Eden, though it is not necessarily purely good as its archetypal predecessor is.

Rather, the Garden reflects a state of innocence, the Ordinary World in which a hero has not yet had to change their lives or encountered any problems.

So the Garden is, in essence, a place of safety and security, a place of nostalgia, and a place of stagnation.

The Garden is necessary in a story because without it there is no explanation for how the hero can exist. While it is possible to forego any narrative emphasis on the Garden, it is usually a core part of the exposition of a story.

The Garden gives us two major points as writers and audiences:

First, it tells us what the world can be when everything is going right.

Second, it gives us something to worry about when the main conflict kicks off.

Having the Garden means that we see the universe through an idyllic lens, getting a chance to become acquainted with its inhabitants and get to know them. It does not necessarily even have to seem idyllic; in the recent Star Wars Solo spin-off movie, Corellia is a lousy place for Han Solo, but it turns out to be his Garden because it gives him the time to explore, in relative safety, the abilities he will need later on.

However, the Garden exists in part to be destroyed, and Solo quickly capitalizes on this when Han makes enemies and has to flee Corellia, something that is both his goal but also the only way that he survives.

This is where we get two narrative stages that take place in the garden:

- Innocence, reflected in the Hero's Journey as the hero's Ordinary Life.

- The Fall of Eden, reflected in the Hero's Journey as the hero's Call to Adventure.

One thing that is noteworthy here is that unlike the Hero's Journey, these stages do not necessarily have to occur, nor do they necessarily have to occur at any particular point in the narrative. Both Innocence and the Fall of Eden are predisposed to coming at the start of a story, but they can happen near the end; in this case it is likely that the story is merely part of a larger heroic tapestry.

Innocence

The first stage at which the story focuses on the Garden shows Innocence, the state in which the world is as good as it is going to get at any point in the story until the very end.

This Innocence is a state in which the Garden appears to be prepared to exist perpetually, and in which the denizens of the Garden find it to be sustainable. This is not necessarily the same as finding it to be good, which is something that comes up as a point of contention in genres with more of a dark tone in which the Garden may itself be flawed.

In any case, however, the state of Innocence is one in which the protagonists face no problems other than their own.

This stage of storytelling is important because it gives the audience a chance to focus on what the themes of the story will be before the action picks up. There are no distractions, so any issues that exist before the main problem occurs serves as a means of orientation in the same way that a light in a dark room allows a person to find their bearings.

The one caution here is that it is important to remember that all of the setting archetypes are defined in relation to their characters. Innocence can occur in a place that is not good–morally or practically speaking–by our standards. It is merely the resting point of the universe.

The Fall of Eden

The Fall of Eden is the event that signifies the story's shift away from the Garden. In the Hero's Journey, this is often the Call to Adventure, but if you are telling a story with a lot of characters involved, you might not make it such a dramatic impetus and it may even be an event in a character's backstory or something that drives the rising tension of a story.

In some cases, the Fall of Eden can be a way to start in media res, but without making the characters feel disconnected from their universe. That way you can provide context for settings and backgrounds without going through a slow moment at the beginning of the story.

One caveat is that the Fall of Eden requires a corrupting influence, something that is usually the impetus for a Hero's Journey. However, stories have been written in which characters do not necessarily rise up to the standard of heroes; Steinbeck's Grapes of Wrath comes to mind as an example of a story that uses this Garden archetype's Fall of Eden as an impetus for a more anti-heroic story of the Great Depression.

In Grapes of Wrath, it is the setting archetypes that are often the most convenient measuring points; it is a tale of sojourning, and the Fall of Eden is a great way for a storyteller to set up a journey and explain why you might find less heroic characters traveling outside of their comfort zone and confronting the supernatural world.

The Fall of Eden changes the Garden–it is no longer safe, or the protagonists are no longer welcome. Sometimes both changes occur simultaneously, especially in dystopian fiction where the horrible truth about their home becomes obvious to the heroes.

Because of this loss, the Fall of Eden is a powerful tragic archetype, creating a mood of sadness and uncertainty for the audiences in much the same way that the threatening of a character changes the mood; however, because the setting serves much as a road that guides the character's more direct relationship to the action, a storyteller can destroy or corrupt the Garden–and make it into an icon–without disrupting the plot in the same way that a character's death might.

This is especially important in games, where players tend to resent having a scripted death unless the circumstances align to make it expected or acceptable. Since such things tend to be difficult to manage at the beginning of a story, the Fall of Eden serves as a way to transform the Garden into a symbol of loss, motivating the protagonists to rebuild the Garden or find a replacement (both of these would be the Promised Land).

How to Use the Garden in Storytelling

The Garden is powerful as a tool because in its perfect forms (where there is no prevailing corruption or problems in the Garden) it is a place that evokes youth, fertility, and prosperity. It reflects an ideal that is worthy of being protected and nurtured.

In less idyllic Gardens, the place is still used as a shelter and respite from harsher parts of the world; it may be imperfect and unpleasant, but it is somewhere that is knowable and relatively stable.

Further, it is a place where the characters can generally linger (at least until a Fall of Eden), which gives storytellers a place to control the pacing and momentum of a plot.

Because a particular point in space is not as important as the conceptual space which it occupies, it is possible for a place that is once a Garden to become something else; in the Hero's Journey any return to the Garden before the end of the main story typically necessitates its transformation into something else (often, the Garden is destroyed if the hero returns), that makes it difficult. However, in longer stories and in larger spaces, it may be possible to transform the Garden slowly, making it manifest elements of the supernatural world of the Hero's Journey. Being a place no longer fit for ordinary people, it can transform into a place that holds dangers and wonders in its own right.

Deus Ex: Human Revolution does a good job at this in its depiction of Detroit; at first it is a sandbox with a number of issues for the protagonist to deal with, but they are largely scattered and not critical to the storyline, but as Adam Jensen returns time and again to Detroit it shifts, becoming more hostile and more dangerous to reflect the Road of Trials that Jensen has departed on in his Hero's Journey.

The Garden doesn't necessarily have to be the starting point of a story, but for a storyteller it provides an opportunity to test the waters; when I use the Garden as I run a roleplaying game I use it as a way to give a low-consequence learning curve to players; this is especially important in games where you may not have characters whose players wish to immediately start the Hero's Journey, and who may need to be hooked into the evolving narrative through carefully created hooks.

When the time comes, either the players leave of their own accord to investigate some foreign threat, or a Fall from Eden occurs and the Garden is destroyed, forcing the players out into the world.

A good way that the Garden can also appear in a story is not to have it appear at all, but rather make oblique references to it. In Mad Max: Fury Road, Furiosa leads everyone on a trek across the wilderness to find a land of plenty where they can live in peace away from the regular bands of post-apocalyptic misfits.

However, upon arriving at the land that was once her home, the story changes to reveal that since Furiosa left/was taken from her home, a Fall from Eden has occurred. Since we have a lens into the universe by the means of the characters' perceptions, this place serves as a Garden for Furiosa and a Promised Land for Max and the others.

Its memory serves a model for later in the story, when they return to defeat Immortan Joe and abolish the oppressive society that he has created.

Wrapping Up

The Garden is a setting archetype, a way of approaching a place as you tell a story to give it particular meaning. It offers a place where the story can proceed slowly, building connections between characters and events so that when the story picks up the audience can follow it–it also is a place that can be treasured and sought after, and serve as a model for the Promised Land later in the story.

Hi loreshapergames,

LEARN MORE: Join Curie on Discord chat and check the pinned notes (pushpin icon, upper right) for Curie Whitepaper, FAQ and most recent guidelines.

To listen to the audio version of this article click on the play image.

Brought to you by @tts. If you find it useful please consider upvoting this reply.

I realized that I didn't give enough examples to fully develop this (not that I could really cram much more into this; it's 2000+ words already), so you can find more here: https://steemit.com/storytelling/@loreshapergames/the-garden-in-motion-analyzing-setting-archetypes-in-fiction-and-gameplay

excellent article RPG is going up!