Using Archetypes: Setting [Part 1: The Journey's Steps]

Right now I've been working on setting stuff, and while I'm not fully ready to go into detail on it, I want to talk about some archetypes that I consider to be the basis for a setting.

Settings are often overlooked for the archetypal forces that they are. This isn't to say that settings are necessarily always as well developed as they should be; you can't have a Hero's Journey without a strong character, but you might get away with one without a setting that matches.

With that said, I think that a lot of our displeasure with stories can come from the disruption of archetypes, and that one reason why a lot of more recent movies have been panned is that they've begun to move away from principled archetypal storytelling in their places, in part because these setting archetypes are often seen as carrying baggage. I would argue that it's the baggage that these places carry that makes them worth having.

Without further ado, I want to talk about the setting archetypes that I've identified. These are not necessarily going to be the same as anyone else's, and I'm sort of kicking these out here without really doing research. These are also probably not final and total, but I'm sketching quickly instead of broadly. I'm not the first person to tread this path, but I'm going to hazard this guess and go into more detail later.

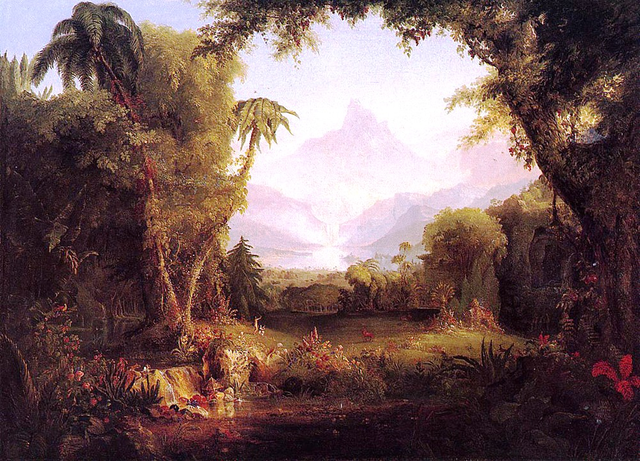

Eden

Eden is the place of perfect harmony before the goodness of the world begins to falter. This is the ordinary world of the Hero's Journey.

Before a problem arrives, this place is perfectly livable for the hero. It may not be perfect, as the Biblical Eden, but it is going to be a place where their existence is bearable.

At some point, a problem occurs in Eden. This may be the result of an interloper from outside the world (the Serpent, for instance, does not belong to the world of paradise and pleasure), or some problem that the hero notices if his Eden is not necessarily perfect (and the archetypal Eden does not have to be).

Gateway

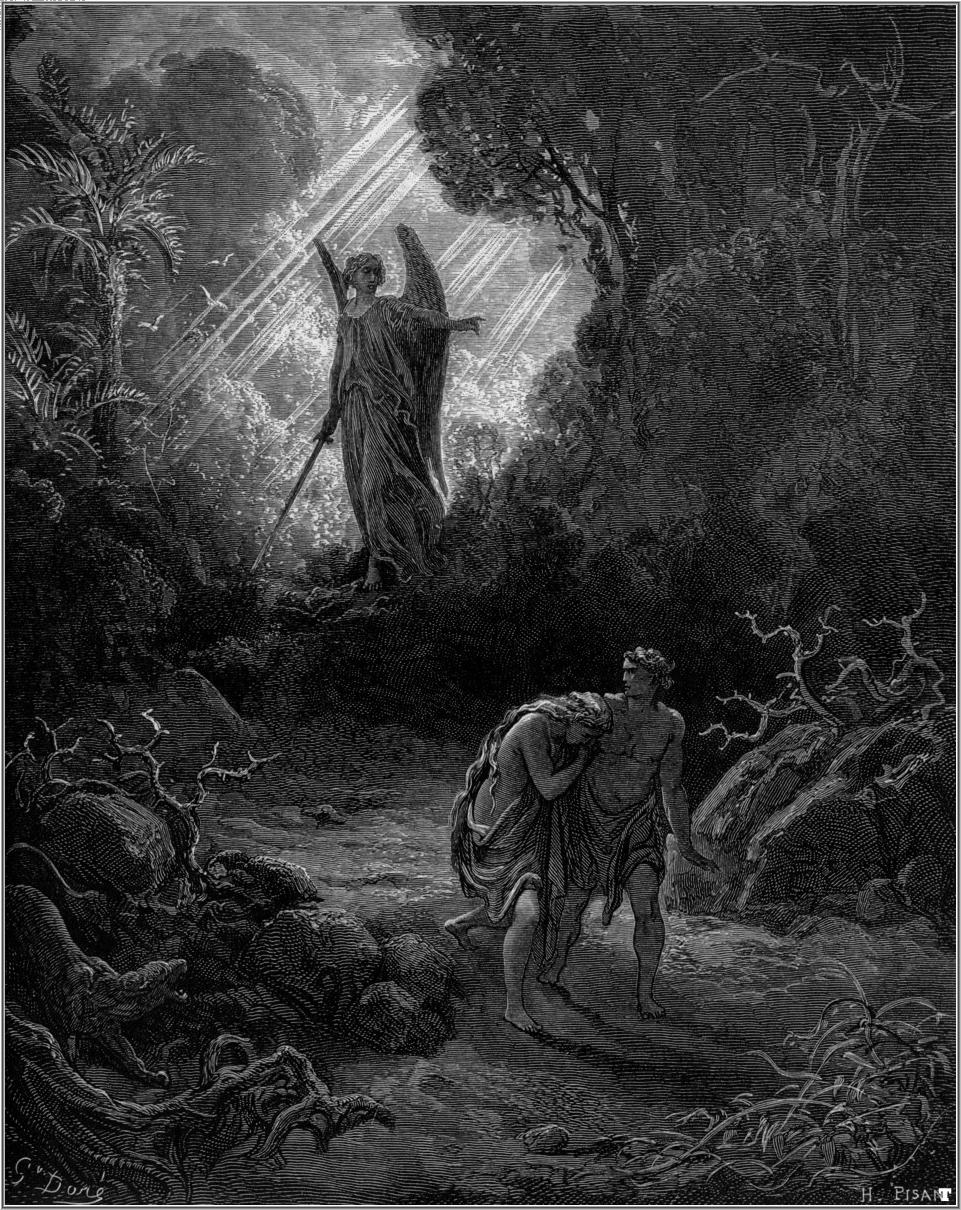

The Gateway is the transition between Eden and the greater world. It is a place that every hero must pass.

An important point about the Gateway is not that it is the way out of Eden. Eden can end in a variety of ways, although the hero's path leads by only one. The Gateway, however, shuts behind the hero, locking them out of paradise. They must deal with the cause of their fall before they can return (the Christ-story serves this role in Christianity, opening the Gateway to Eden once again).

The Gateway in stories may be a literal point of no return, but often it is simply a milestone that the hero passes on their way out of town. Bree in The Lord of the Rings is an example of this: by the time Frodo is here he cannot return to the Shire until he has completed his quest. To do so would be to accept catastrophe.

Gustave Doré's Expulsion from Eden

New World

The New World is the place that the hero finds themselves in after leaving Eden. It is a place where there is always some potential for change and improvement, not fully consumed by the evil outside. There may be some challenges here, but it's nothing that is going to be insurmountable, and the hero finds help from its inhabitants.

In this place, there is still the chance for evil. Treason and treachery will first show up, though they will be restrained. The forces of the Adversary and Nemesis are not present, but their influence may still be felt.

The New World is nonetheless a place of hope and opportunity. Even an anti-hero, in their weakness, can manage to find their way in this place. Tolkien again provides a good example in the form of Rivendell, where the Fellowship can seek respite during the path away from home.

Exile

Exile is not necessarily a single place, but it is the Road of Trials in physical form. For Odysseus, Exile is a series of islands and adventures that are strung together. For the ancient Israelites, it was forty years of wandering in the desert.

Exile strengthens and removes weakness. It is harsh and unfeeling, but not necessarily actively hostile. This is the world of sin and decay, away from Eden and even the comforts of the relatively uncorrupted New World.

It's worth noting that the Exile is simply a manifestation of the Road of Trials. It could be broken down further into different places, as the Road of Trials in Campbell's monomyth can be broken down into a variety of places.

An example of this is Utopia, where the protagonists seem to reach a perfectly happy place (the Land of the Lotus Eaters, Galadriel's domain, Egypt) only to realize that there is some greater call that pushes them onward.

Abyss

Abyss is the worst and most dreadful place that the hero must go, the home of the source of the troubles for their people. Each Abyss can be different, but it almost always requires that the hero go into some extreme personal danger; Jean Valjean mans the barricades, Christ harrows Hell, the Israelites are forced into exile in Babylon.

The Abyss is the home of the Adversary, or at least their domain. It is Mordor, Hell, or Room 101. Within the Abyss, the hero faces their greatest challenge. It seems they may have to die to do so (and, in some cases, they do: this is common in movies where a character will seem dead and then recover after attempting some heroic sacrifice).

The power of the Abyss is not to be taken lightly; the place itself is hostile, and its inhabitants are often of a separate world onto the separate world that the hero has entered.

Return

Return is the path home. It is the place that will lead the hero back toward what they have sought all along. The Return is life, but it is not necessarily easy. The path is not straight, nor is it broad, and the hero may face challenges.

The Return is a way of testing commitment. If Odysseus were to cower in front of the might of the suitors, he would abandon his Return. If the Israelites were to become comfortable in Babylon, they would never be permitted to return to Israel. If Christians sacrifice their pursuit of God as their highest goal, they are not worthy of entering into Paradise.

This is not to say that it is not a test of strength, but with the Adversary defeated, or at least forestalled, nothing can stop the hero at this point other than a lack of will.

Promised Land

The Promised Land is the perfect world that the hero set out to create. It is not necessarily a literal perfection, but rather a figurative perfection within the boundaries of their needs and desires, that defines this world.

Returning to the Promised Land demands a return to the old ways of life; the Israelites must reconsecrate themselves and rebuild God's Temple. The hobbits returning from their journey must remove Saruman's influence from the Shire (itself a statement of Tolkien's desire to see a more harmonious, less class-structured society).

While it is rare for a hero to taste the Promised Land and reject it, they are often forced to come to grips with the fact that their efforts to change the world have made it a different place.

Application to Storytelling

The storytelling side of this is that you need to consider, as a storyteller, the role of place in the Hero's Journey. I remember Ready Player One (the novel; I have not seen the film) doing this quite well. The protagonist starts out in a trailer park of sorts, his home, completing his education in a virtual school (where no violence is possible or permitted–does this sound familiar?). From this Eden, he passes on into the New World, with his Gateway being the destruction of his old home.

Completing his studies, he has no reason to remain in the educational sections of Oasis, and as he is now forced to be on the road, he cannot even attempt to return to his old Eden: at least not without the threat to his life removed.

Eventually, after a fair amount of moving around and moving up the social ladder (Exile), he joins forces, albeit under a false identity, with the corporation that has been hunting him, falling totally into the Abyss.

With cleverness and duplicity, he is able to negotiate his Return after figuring out what he needs to know about IOI so he can save his friends and begin to change Oasis into the Promised Land it could be under his control.

Finally he triumphs, resulting in a new Promised Land: the Oasis in good hands.

The Hero's Journey is often told from the perspective of the hero, but the places it follows are just as important: they convey the mood and tone just as well as a character can, and provide more external imagery while doing so.

Application to Gaming

If you are designing a game world, you need to consider the role that these places have in creating understanding and attachment. These archetypal locales tie to psychological needs, and reflect the development of the mind from an infantile state to an adult state.

One of the things that can be damaging to this sort of storytelling is the "hub level" seen in many games. While this works to a degree in many games, one of the greatest flaws that can occur is if this removes the Hero's Journey from the story: the world needs to change and react, and having a world that simply encourages stasis is going to cheapen your story.

If you do not want to force linear play, consider writing story arcs that take players into places that are inspired by these archetypal settings. Use them in individual sessions even; hunting a murderer can be a simple maze of locations and clues that challenge players but do not engage them, or the process of going on an adventure that leads into the Abyss of a killer's lair.

Wrapping Up

Archetypal places are important; they resonate with our lives on a deep level, and they can hold power that is often not exploited. A good archetypal setting will provide the readers with the appropriate mood for the stage of the hero's journey; the Abyss brings fear and terror, Eden brings peace and contentedness, and the Promised Land brings joy.