The Biscuit Shrub - a Short Story - Sndbox Summer Camp Writing - Task 2

Ivan Rynkiewicz has an old, crumbly two-seater couch on his front porch. My next door neighbour once said something needed to be done about that old Polish man, that his house was a disgrace; it was lowering the street's land values.

Ivan Rynkiewicz sits on his porch couch with a long stick in his hand, and waves when my son and I walk by. He is often in his garden, his sweet-smelling garden, and he leans on his stick to gaze over his handiwork. Sometimes when we walk by he is down on his knees pruning. He even looks creaky, but gets to his feet all right to talk to us.

My son, Jack, and I are walking up the street to the supermarket. I am stressed with the familiar self-imposed pressure of unattainable tasks. I want to get to the supermarket so we arent sitting down to eat dinner at 8 o'clock. Again. As we near Ivan Rynkiewicz's house, I half hope he's inside so we can rush past.

Ivan Rynkiewicz is pruning the rosebushes that run along his front fence. The roses are apricot, yellow, orange and white, profuse in both colour and smell. Now, there's something about Ivan Rynkiewicz that is instantly calming. As soon as we start talking my unattainable tasks begin to seem just that - unattainable - and then I can slip easily out of the bubble that seems to descend on me every mid-morning. Ivan Rynkiewicz has this effect on me. I don't know why, but somehow I get a little stoned in his presence. I wish I could bottle him up and take him home with me.

Of course, slipping out of the mid-morning Clean All This Crap Up performance bubble means that we will be eating dinner at 8 o'clock again, which will send me to biting my nails in the evening vowing that I will be more organised tomorrow and so it rolls on every single fucking day.

Ivan Rynkiewicz's cat comes out of the driveway onto the footpath, and begins languorously weaving its way around Jack's shorts-clad legs. Jack giggles, resisting the urge to touch it so that it won't stop twining around him, like it did the last time we were here with the instant changeableness common to cats. My heart aches.

"Hello, Ivan," I say, his name sounding funny on my lips. Eeevarn. I always think of a whole bunch of things when I think of Ivan Rynkiewicz's name. For a start, I find it hard to say anything but his full name in my head, because its singsongness always calls. Then straight after that I think of Tinky Winky and those stupid bloody Teletubbies. Then I think of Ivan Lendl, the tennis player. Then I think of Ivan Hutchinson, an Australian movie critic from my childhood, because he's the only other Ivan I can think of, even though his is an Eyevin Ivan, not an Eevarn Ivan. Then I think of how English sometimes takes names and bastardises them down into something flat and stupider than they were when they were something else that's not English.

All of this takes place in a flurry of a second while I am saying, Hello, Ivan. I feel a bit naughty calling him by his first name. However, he has insisted on so many other occasions that I keep trying, hoping the word sounds less constrained to my ears each time.

"Ahh, here zey are! Mr and Mrs Barone!" Ivan Rynkiewicz smiles at us, creasing his eyes. "And zvere are you off to today, eh, Jack?"

It is perhaps considered culturally inappropriate for me to render Ivan Rynkiewicz's speech in this fashion. Something theoretical about it demeaning him somehow, sideshowing him. I don't know anything about that. All I know is that this is the way Ivan Rynkiewicz sounds when he talks, and if I can paint him true I will, and this is a flavour particular to him, one scent that makes up his whole, and so I write it so. After all, I don't care about Ivan Rynkiewicz's depiction as compared to the entire Polish population, or about making myself appear better than him in my white supremacy. I don't care about all of that power stuff; I just want to hear him in my head again, that's all.

Ivan Rynkiewicz has a dog, an old golden retriever named Gisia. The dog lies in the front yard, thumping her greeting on the lawn. Jack wanders into the front garden.

"Jack," I begin protesting, "you cant just invite yourself into people's gardens like that. Now, answer Ivan's question." I can hear the droning fishwife in my own ears. It makes me squirm.

"Ah, hes all right. He's just coming to see Gisia.”

Jack flops down next to Gisia and pats her golden coat.

"You like ze animals, Jack. And zey can tell that you like them, because zey like you too. You are very good viz zem."

"Yeah. I love cats and doggies. But doggies best. Ones like Gisia." Jack lies alongside Gisia and begins talking to her and patting her. I make a mental note to talk to Harvey again about getting a dog for Jack. Ivan Rynkiewicz and I watch them for awhile, in silence. He smilingly turns to me.

"He is so gentle viz ze animals, Jessie. It is good to see in such a young boy."

I nod. "Especially since hes so rough the rest of the time!"

Ivan Rynkiewicz nods. "Yes. It is so hard viz children, yes? Very tiring. I remember viz my own children, and if I am about to forget my grandchildren remind me!" He laughs, and I nod again. It is tiring. Sometimes I'm so tired I dont want to get out of bed. And now I'm pregnant again, its even harder.

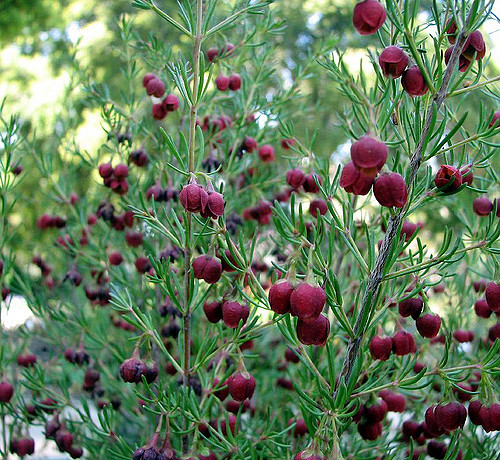

There is a shrub in Ivan Rynkiewicz's garden, in the corner where the front and side fences meet. It has hard, rounded, dark pink buds and it smells like Iced Vo-Vo biscuits. It sends me wheeling instantly back into my childhood whenever its scent wafts like a gift into my space.

I feel Ivan Rynkiewicz studying me for a few moments. I don't flinch from his gaze. It is kind and benign. If he can see my frailty, its nothing to him. I can feel that.

“Vould you like to come in for a cup of tea, Jessie? Take a load off your feet and let ze boy play for a while viz ze dog?”

I hesitate. The supermarket is calling its fluorescent, boring siren song. But it's nice here. There is a certain feeling that pervades the air around Ivan Rynkiewicz, a nondescript old Polish man who you probably wouldn't look twice at in the street. It is a relaxed feeling, yet alive with possibility at the same time, and I feel it also inside his clean, tidy, rundown house. It is a feeling I try to achieve with candles, incense and tealights, and which Ivan Rynkiewicz seems to achieve by breathing.

I sometimes like to think I remember being a baby - the total immersion, like in a bath, envelopment in the moment. The delight of learning that I can manipulate my own body, that my foot reaches my mouth, an at-one feeling with the walls, the ceiling, the shaft of light on the floor. It is this same feeling I feel with Ivan Rynkiewicz. Whenever I see him he seems total, and whether happy or sad he seems to just accept it and ride it. It gives me hope.

The cat, it turns out, isn't Ivan Rynkiewicz's cat at all. It belongs next door, but knows which side its bread is buttered on. It spends most of its time weaving around Ivan Rynkiewicz's front garden, and now has followed us into the house to leap onto a couch in the lounge room.

I sit there while he goes to make a pot of tea. I can hear him laughing with Jack in the kitchen. They are laughing at the magpies flapping in the birdbath outside the back door. Ivan Rynkiewicz's laugh is very loud. There is no tapering of it at the ends.

I realise I have known this man for four years already, ever since we bought the house. And yet this is only the second time I have been inside his home. I have, however, been inside his garden countless times. Sometimes, on days when I feel cut adrift, I go past just in case he is there, so I can sit in his garden.

I have learnt a bit about Ivan Rynkiewicz in four years. He has told me of his immigration to Melbourne in the late 60s with his wife. I know of his wife's death in 1975, of his three daughters and their children.

I realise how little Ivan Rynkiewicz knows of me. It is not a purposeful thing, but I have a habit of closing myself off. I know this because once a friend screamed it so, right into my face. And I know, too, that sometimes Harvey and Jack seem awfully far away from me. This scares me, and makes me feel guilty. Ivan Rynkiewicz sometimes gives me the impression that he could know things about me that I don't and it wouldn't be such a bad thing. Sometimes I think telling someone else every single thing about yourself would make you feel as big as the moon.

He comes into the lounge with a pot of tea and two cups on a tray covered with a lace cloth. There is a glass of something for Jack. He places it all down on the table between our two chairs and calls Jack in.

The boy and the dog bound in. Gisia enjoys his company - despite her advancing years, she's still partial to a bound. Jack takes the offered glass. He drinks half of it, eager to please Ivan, before making a face.

"Yuk. I don't like it." He wipes his mouth with his sleeve.

I sigh. Jack is so upfront, so rude; it is embarrassing. But Ivan Rynkiewicz just nods his head."

"It is lemonade I make at home, Jack, but it is not as sweet as ze uzzer stuff.”

Jack nods, then shakes his head. "Yeah I mean, no, it's not very sweet. Hey, but if this is lemonade, why isn't there bubbles?"

Ivan Rynkiewicz creaks out into his kitchen, explaining to Jack the ways of carbonated beverages. Then the screen door slams, and I hear the boy and dog outside again.

"Zat is good - he vas happy viz vater," says Ivan Rynkiewicz, entering with another tray containing biscuits. He places the tray next to the other on the table and settles himself into the chair with a satisfied grunt. I pour the tea. I don't want Ivan Rynkiewicz to have to move again to make the tea. I feel guilty that he has gone to this effort when he could be resting. I say as much.

"Ah, no, Jessie. It is good for me to move around. I get stiff too easily if I sit too long in ze one spot. Anyvay, it is nice to see you again and make you some tea; you look a bit tired today."

"Well, I am, because I'm pregnant again, you see."

"Ah!" He claps his hands. "Zat's vonderful!" Ivan Rynkiewicz grins, delighted, as if he was having the baby himself. He looks at me.

I shrug, smile, and then burst into tears. They come without warning, coursing like hormones through my body.

"Oh, Mr Rynkiewicz, I'm sorry. Oh, how embarrassing!"

I'm trying madly to stop those fucking tears. I feel funny crying in front of Ivan Rynkiewicz, but he seems neither embarrassed nor annoyed.

"It is okay. Feel better now?"

"Um, yes. Thanks. I don't usually do things like that. I don't know why it happened."

Ivan Rynkiewicz chuckles. "You remind me. My wife, Sarah, she did ze same viz our daughters. Actually, I remember liking it because it vas nice to be able to help her feel better. It is hard for ze man just standing by, like a palant, like an idiot.”

I pass Ivan Rynkiewicz his tea, which he takes, hands only slightly trembling, and puts on his lap.

"I am seventy-zree years old, and I still remember zose times very clearly. It is hard. Sarah and I did not know anybody when we came here. It vas hard for her viz ze girls. But zen," he smiles, "we made some friends, and soon we had people to look after ze girls so we could go to the museum by ourselves."

There is something about the way Ivan Rynkiewicz tells stories that I like. It is not so much the content although it is nice hearing somebody being refreshingly honest. Maybe it is his accent, but every story or snippet he tells has a quaint, lyrical sound. My conversation always feels as flat and dull in my own ears as my broad Australian accent. Ivan Rynkiewiczs conversation is reminiscent of Sunday markets and street festivals; mine sounds like Safeway supermarkets and traffic snarls.

Ivan Rynkiewicz has a special lady friend from the Polish church he goes to. I have seen her within his garden a few times. She is loud and funny. Her name is Ania. She is 62, a spring chick, testament to his vitality.

One day, when Ivan Rynkiewicz is almost 74, he invites me to the small wedding ceremony he and the soon-to-be Mrs Rynkiewicz will be holding in his garden in a fortnight's time. The rest of the day, I trip through life. The air is full of charm when a 74 year old man is getting married.

There are 11 adults and nine children at their wedding. Ivan Rynkiewicz had invited Harvey as well, but in the bit where I think things I will not admit to myself, I am glad he had to work. We sit on chairs in the backyard. The ceremony itself is informal and pretty. Ivan and Ania sit on chairs so that they don't get tired standing up. Afterwards, I sit amidst the free-flowing conversation. There is an Iced Vo-Vo biscuit tree in the backyard as well. Its fragrance wafts past my nose while I talk with the Rynkiewicz children, all of whom seem pretty chuffed that their dad's remarried. Everyone makes wedding night jokes. Ivan Rynkiewicz laughs that laugh.

Gisia has a ribbon for the occasion. She pads around happily after the stream of children. Jack runs around with them too, making aeroplane noises. The children have to be shushed every few minutes so that we can all hear each other. They quieten down for about two minutes. Then they become as loud as they were before and have to be shushed all over again.

Ivan Rynkiewicz comes and sits next to me. I say:

"Im so happy for you, Ivan. Every time I have thought of your wedding, it has made me happy."

"Ah, I am glad it rubs off on you. I am very happy viz my new wife. I was not really looking for anozer wife, but ve found each other anyway!"

This is the thing about Ivan Rynkiewicz that makes me wonder if I'm trying too hard. The way he talks, he seems content with whatever life dishes out, squeezes the essence out of every situation and learns from it. Perhaps it is a heritage of his Polish background; I have no idea about Poland. I know he lost relatives during World War Two. Maybe this was a crossroads, where he had the choice to accept life or die inside.

Sometimes I am running so hard just to hold everything together, to stop everything seeping over the sides, to delve any deeper. This contentment that Ivan Rynkiewicz has, I have no idea how to get it. I have a sneaking suspicion I don't have what it takes to carry it.

There is classical music playing on a stereo near our table. It is in marked contrast to the horde of children whooshing around the garden. I can hear the music when they quieten down. It is pretty, soothing, uplifting.

I ask Ivan Rynkiewicz to dance, and his eyes gleam. He almost jumps up. I am worried, as soon as I ask him, that dancing will be too much for him. But he makes a better fist of it than I do, swirling me around till I am giddy. All Ivan Rynkiewiczs guests watch us, smiling. The pregnant woman and the 74 year-old man.

Ivan Rynkiewicz is 77. He and Ania seem as if they always were. I notice when I walk past with Jack and Georgia that he seems to be spending a little less time in the garden. He's still out there a lot, but is spending more time on the crusty old lounge on the front porch. We spend more time in the lounge room, where the smell of the biscuit shrub wafts in through the open window.

I decide after dropping Jack at school to stay awhile and chat. The housework can wait. I always take advantage of this desire when it comes, because most of the time I am driven to get everything done. You know, I really want to spend more time playing with my children. I want to be able to do it without feeling guilty about not getting the housework done, but it's like a driving force. And I don't even know where that comes from. Strange.

All I know is I don't want to look at the silence. I know I'm running. I have begun going out more often. When friends invite me over, I have started to go, trying not to feel guilty that Harvey is slaving away at work while I'm slacking. Yet it is a catch 22 situation - the more time I spend out trying to escape the dungeon, the more stressed I am when I come home to the mounds of washing and dusty surfaces.

But it's funny how things work I am sometimes disillusioned with visiting my friends, but I never feel that way when I visit this old man. My friends are fun, and l love having adult female conversation. But sometimes the talk of the latest shopping spree leaves me cold. Sometimes I daydream about telling these friends about how sometimes I feel I could lose my mind. They would probably gloss over the surface if I broke the rules and told them.

When we get to the house, Ivan is nowhere in sight. I hesitate. Will I knock on the front door? I don't like to intrude. Perhaps he's busy or sleeping. But I knock, because Ivan Rynkiewicz has told me to.

Ania answers. She beams when she sees us, bustles us inside. Winter is hitting its straps, and she brings us into the lounge room where it's warm.

"Ivan is in bed with a cold," she says, helping Georgia out of her coat, "but he will be pleased to know you came."

Ania is Polish also, but while she has spent about the same amount of time here as Ivan Rynkiewicz, her accent is now only faintly detectable around the edges.

Ania tells me Ivan has had the flu for a week. I worry - he is old. There is talk of putting him in hospital if it gets worse.

Ania is open and honest. “Don't worry too much, Jessie. But still, I think if he feels well enough you should come and see him. Just in case. I'll give you a ring if he feels like visitors, yes?"

I don't know if Ania used to turn her sentences into questions before she was Mrs Rynkiewicz, but now she does. Maybe it's a Polish thing. Like I said, I don't know anything about Poland except that Hitler invaded it. I don't know much about anywhere else, really. Ania makes us a pot of tea, brings it in on the tray with the lace tablecloth. Georgia is tired, and falls asleep in my lap.

Ivan Rynkiewicz sleeps on. Ania tells me that Ivan Rynkiewicz said he feels like I am another daughter to him. This warms me up like the heater is warming the room.

Ania and I look at photos. There is a picture of Ivan Rynkiewicz in his early twenties. He looks like a right deviant, and I laugh. But his eyes are the same crinkly eyes he has now. Ania tells me the stories he has recounted to her of his youth. It seems he had a season of juvenile delinquency in his younger years, stealing things and hassling little old ladies. I stay all afternoon, and refuse to care that the vacuuming hasnt been done.

Ivan Rynkiewicz is dead. Saying it to myself like that is like I'm slapping myself across my own face, but I'm trying to believe that it's true. His funeral is impossible to understand in places because of the Polish. I am here with Jack. I hesitated to take him, but then figure I can't shield him from death forever. Anyway, he loved Ivan Rynkiewicz too. We cry a bit together.

Jack asks me a lot of questions about death, about where Ivan Rynkiewicz actually is. I say I don't know; I can't get up the energy to pretend otherwise to him. I wonder if Ivan Rynkiewicz knew where he was going.

I feel like I have lost my father.

Ania is staying on in the house. She too tells me to come whenever I feel like it, and I will. She is getting old too; maybe I can help her out a bit, take me out of my dreary self-absorption. She has given me the photo of the young deviant Ivan Rynkiewicz to make a copy of.

Ania is staying on, but the Iced Vo-Vo biscuit shrub in the backyard has been transplanted to my front yard, right outside the bedroom so that we can smell it through the open window. What I thought were hard flowers were just buds and now it flowers red. For no reason at all, a couple of months ago Ivan Rynkiewicz asked me if I wanted it. He said he knew I would appreciate it, and that he could plant some perennials in its place. So Harvey and I came down with the van. That was the first and last time my husband met Ivan Rynkiewicz. Funny, isn't it, after all this time? Harvey had liked him a lot, had caught his charm. I wondered why I hadn't introduced them earlier.

We took the biscuit shrub back in the van, with its roots sticking out. It looked obscene somehow, and I couldn't wait to get it in the ground where it belonged. It felt like a lot of trouble to go to for a shrub when I could buy a new one. But then what something means to you isn't stuck on the outside of it with a price tag. Some things are cheap on the outside and so expensive on the inside that no one could afford them.

Pic CC2.0 by Jean

This is my entry into Sndbox's Summer Quest

I must say this ranks among the best things I have read on Steem since coming on board... or anywhere on the internet as a whole. Really awesome and compelling read. I will resteem this too.

Oh my. Well, shucks. Thank you! :)

This is a beautiful story. As an Australian I can relate to this.. my Aunty was Polish and entire family German. I wondered what the iced vovo tree was... does it really smell like that? Ah, we can feel so parochial, can't we? I'd love to read your other stories... this is the best I have read on Steemit thus far. I would love you to read mine and critique but its no where near as clever as this!

Thank you! Are you on Writers Block? I've joined but haven't really done anything there yet. Omce I get my footing (and hopefully maintain current brain ability, critting your story would be cool!)

You know, I wrote this story quite a few years ago now, and ever since then I've been trying to identify what that shrub or tree is. It really does send me back to my childhood. All these years and its identity has remained elusive, so I just went with a red boronia after searching for fragrant shrubs to illustrate this post. I really wish I could suss out what it is. I think they're reasonably common in Melbourne front yards.

I wonder what it was!!! In the story, I imagined a bigger tree being transplanted. I dont know about writer's block - what is it?

critting??

Yeah, they workshop your stuff. It looks really good. Here's their intro: https://steemit.com/writing/@gmuxx/meet-the-writers-block

Thankyou!!! Good tip. Xx

Nice story. Had to write it. Cheers.

Wow, great story. It really does stand out from the rest of the pack.

This post was nominated by a @curie curator to be featured in an upcoming Author Showcase that will be posted early Monday (U.S. time) on the @curie blog. If you agree to be featured in this way, please reply and:

You can check out our previous Author Showcase to get an idea of what we are doing with these posts.

Thanks for your time and for creating great content.

Gene (@curie curator)

Wow, thank you so much @randomwanderings! I'm very honoured.

Please feel free to quote whatever you like and here is my intro:

There really is a shrub or tree that smells like Iced Vo Vo biscuits. I have illustrated my story with a picture of a red boronia but to be honest, I don't know if that's it. Next time I come across it when I'm out and about (which doesn't happen much these days as I'm a house hermit) I shall have to climb into someone's front yard and shove my face in their shrubs until I can identify it. I've been writing short stories for a few decades now and being in the middle of a story is the best of all the best places. It's like being God while at the same time not having a damn clue where your world is going and whether you'll be able to get your characters up and walking about in it. I have many unfinished worlds sitting in stasis on my Dropbox account :)

Oh such beautiful writing! I loved this. And then that last line... This is a really moving story. thank you.

Thank you for reading and taking the time to commemt.