Folktales, Racist Discourse, and Class Struggles in Afro-Venezuelan Literature. Part V

Fuente

Fuente

Greetings, everybody

Thank you for accompanying us in the development of this topic. To finish the series, let us now take a look at the last novel, Nochebuena Negra, and how the folktale characters are used here.

You can check the previous publications in the following links:

Part I:

https://steemit.com/powerhousecreatives/@hlezama/folktales-race-and-class-struggles-in-afro-venezuelan-literature

Part II:

https://steemit.com/powerhousecreatives/@hlezama/folktales-racist-discourse-and-class-struggles-in-afro-venezuelan-literature-part-ii

Part III:

https://steemit.com/powerhousecreatives/@hlezama/folktales-racist-discourse-and-class-struggles-in-afro-venezuelan-literature-part-iii

Part IV

https://steemit.com/powerhousecreatives/@hlezama/folktales-racist-discourse-and-class-struggles-in-afro-venezuelan-literature-part-iv

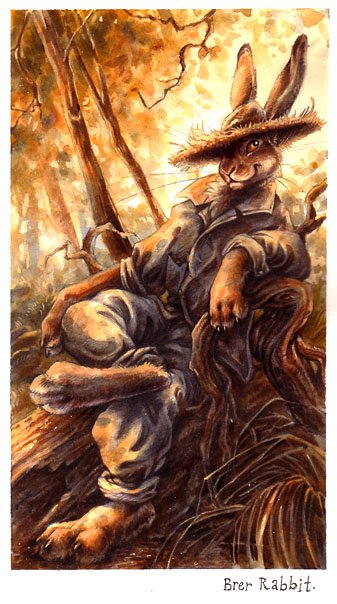

Conejo de Nochebuena Negra

Fuente

Fuente

Juan Pablo Sojo’s Nochebuena Negra (1943) has been praised as “the most important fictional affirmation of black culture published to date in Venezuela” (Lewis 2). It shares the same artistic and social elements most Venezuelan novels on the subject have (realismo mágico, costumbrismo, historical references, miscegenation, tragic mulattoes, etc); yet, Juan Pablo Sojo’s approach does not privilege white culture; on the contrary, Sojo considers the possibility of preserving Afro-Venezuelan traditions, and criticizes the dominant culture for perpetuating the socio-economic gap and succumbing to “whiskey, dances, tennis, and elegance. The whole history of a Society” (176).

Luis Pantoja, the newly arrived administrator at the Sarabias’ hacienda, is Don Gisberto’s nephew. His appointment is a surprise for Crisanto Marasma (the butler), who feels fooled because Don Gisberto did not grant him that promised position. Crisanto is the father of Pedro and Deogracia. Pedro, the progressive son who left Barlovento to pursue an education and a better life in the capital, becomes a key character in the novel. He would fall in love with Consuelo, Don Gisberto’s niece. Because of class and racial issues, this romance will be forbidden and the two lovers will have to conform to the social norms and continue their lives separate ways.

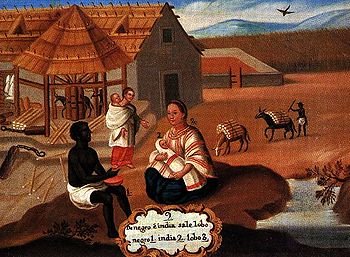

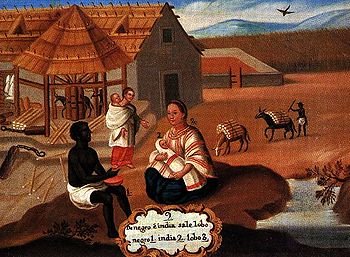

But, this romance is marginal to the more transcendental events in the novel. There are at least five parallel stories that are told and all of them are inter-connected by the racial and class tensions that drive the characters’ world. We read, like déjà vu, phrases that resonate from other Afro-Venezuelan texts: “they were all ingenuous people, ‘poor blacks’ from Barlovento” (16); “the soul of blacks is like the soul of singing springs, clear and ebullient” (17); “[no matter for how long I worked]I never ended paying back the one hundred and fifty pesos that Dr. Goyo paid for me...” (42); “It is the office that has evoluved in them, a race of tree felling peons, or head-choppers in the civil war raids” (44); or “The Indian is vile to death” (78).

Source

Source

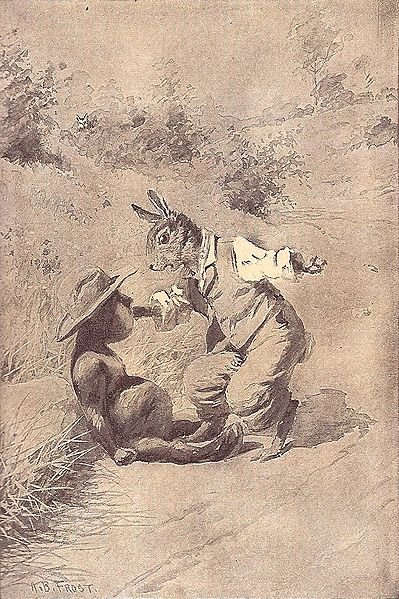

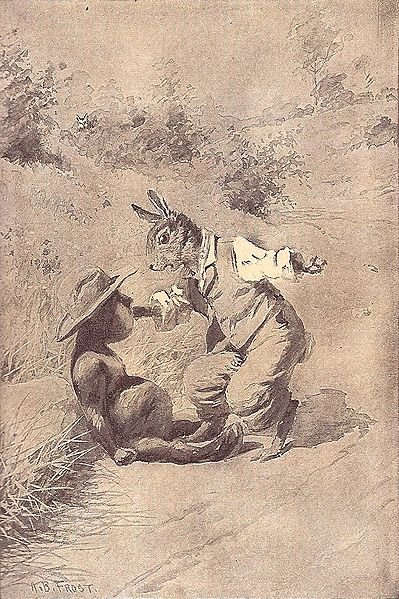

Thus, in the same way we see fierce animosity against the zambos in Pobre Negro, en Nochebuena Negra it is against the Indians that some of the attacks are directed. And, it is precisely through a Tío Conejo story that the author chooses to set up the scene that will pretty much define the tone of the novel. Lino Bembetoyo is the Negro Malo of Sojo’s novel. He is an oversexed black, and he takes pride in it. He hates whites as much as he hates Indians; but his dislike of Indians comes more from ignorance and prejudice than from actual experience. Guaraco, his brother in law, is an Indian. He was a foreman at the hacienda of Dr Goyo. “He came running away from the hacienda after swimming across the Tuy [river] and show up at Lino’s shack...” (27). Lino could hide his in-law well enough not to be found in days, but he could not stand Guaraco’s sneer.

Fuente

Fuente

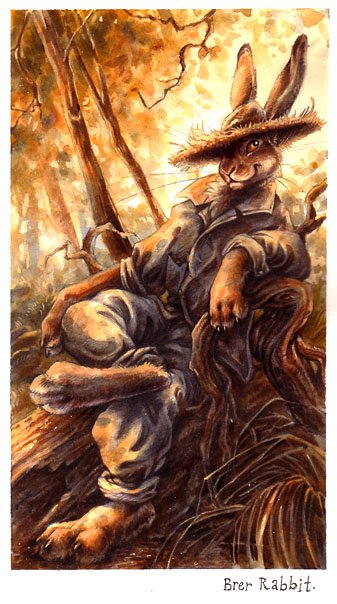

Thus, during a gathering at his house, Lino decides to get even at Guaraco, who had subtly alerted his sister that Lino was flirting with one of the guests (28). “This is a tail of when animals could talk,” he begins. “Rabbit, who was the most Indian of the herd, for his cunning, went to father God and told him...” Thus, Lino tells his version of how rabbit got his big ears. The rabbit, according to Lino, having successfully completed the tasks, despite his physical disadvantages, earned Papa Dios’ cautionary remark: “‘Indian and rabbit are the same thing because of their cunning! If I make you bigger, my son, what would be of the other animals, if being as little as you are now you have done everything I asked from you?’... That’s why you can’t trust either a rabbit or an Indian!” Lino concluded.

As I mentioned in early in the series, Guaraco’s smile had to do with his listening to the praising his boss was receiving; he, who had worked for the doctor, knew what kind of a trickster Goyo was. After Guaraco tells Lino the details of how Dr Goyo got rich “out of extortions and criminal expropriations,” and all the things he became a victim of, “Lino understood the hatred and despise hiding behind that sneer of the Indian. Guaraco had a man’s heart” (43).

By allowing Lino and Guaraco to become allies against a common enemy, Sojo denounces the pernicious divide-and-conquer practice surreptitiously imposed by centuries of racist colonization. The fact that the animosity among non-white groups can lead them to recur to what otherwise could be used as their folk hero to denigrate one another, demonstrates the extent to which dominant ideologies and classicist/racist essentialism permeates the most fundamental layer of cultural manifestation to become part of the psyche of those who are meant to always be subjected.

Source

Source

Despite the alleged lack of racism in Venezuela, we know that the colonial discourse established the foundations for a profound disregard for any skin pigmentation other than white and that, “interpolated” by this discourse, both whites and non-whites (mestizos, blacks, Indians, and zambos —probably in that hierarchical order) have historically attacked or (at best) competed against each other. Tío Conejo stories have been part of this dynamic/discourse; it has been appropriated by multiple voices, for multiple purposes; he has become, then, some kind of liminal space, the wanted/rejected inheritance, associated at times with the best/most subversive part of the Venezuelan roots, but often times with what Venezuelans, as a post-colonial nation, think is the worst of their racial mixture: the cunning of the Indian, the laziness of the mulatto, the untrustworthiness of the zambo.

Thanks for your visit

Obras Citadas o Consultadas

Arraiz, Antonio. Tío Tigre y Tío Conejo. Caracas: Monte Ávila Editores, 1980.

Díaz Sánchez, Ramón. Cumboto. Caracas: Editorial Panapo, 1997.

---. Paisaje Histórico de la Cultura Venezolana. Buenos Aires: EUDEBA, 1965.

Gallegos, Rómulo. Pobre Negro. Buenos Aires: Espasa-Calpe, 1945.

Lewis Marvin. Ethnicity and Identity in Contemporary Afro-Venezuelan Literature. Columbia: U. of Missouri P., 1992.

Piquet, Daniel. La Cultura Afrovenezolana. Caracas: Monte Ávila Editores, 1982.

Ramos Guedez, José Marcial. El Negro en la Novela Venezolana. Caracas: UCV, 1980.

Sojo, Juan Pablo. Nochebuena Negra. Caracas: Editorial General Rafael Urdaneta, 1943.

Wright, Winthrop R. Café Con Leche. Race, Class, and National Image in Venezuela. Austin: U. of Texas P., 1993.

Visítanos en: www.equipocardumen.com.ve

Visítanos en: www.equipocardumen.com.ve

Fuente

Fuente

Fuente

Fuente Source

Source

@hlezama,

Great analysis. It never fails to amaze me about the significance some people put in the concentration of melanin found in the sub-surface of one's skin. How stupid do you have to be if that is the basis of your judgement-making? Indeed, it would seem like such an obvious short-coming in critical thinking that one would assume it would adversely effect survival ... like being unable to distinguish between a lion and a housecat just because they both say, "meow."

Stupidity is color-blind. So is genius. And so is character.

Quill

Thanks for stopping by, Quill.

Unfortunately for us, this has been one of humanity's greatest and most consistent flaws. Centuries of experience, setbacks, lessons taught, knowledge, etc. have served no purpose in trying to stop this fixation from influencing the way we interact with people.

On the personal level that would of little consequence, but when we have entire governments or nations mapping their allies and enemies based on racial features and may or may not be then connected to other cultural aspects, then we have the big problem that prevents us from realizing all our so-called human potential.