Folktales, Racist Discourse, and Class Struggles in Afro-Venezuelan Literature. (Part IV)

Fuente

Fuente

Greetings, everybody

Thanks for accompanying us in the development of this topic. Let us now take a look at how the folktale characters are used in every one of the novels mentioned in the previous posts.

You can check the previous publications in the following links:

Part I:

https://steemit.com/powerhousecreatives/@hlezama/folktales-race-and-class-struggles-in-afro-venezuelan-literature

Part II:

https://steemit.com/powerhousecreatives/@hlezama/folktales-racist-discourse-and-class-struggles-in-afro-venezuelan-literature-part-ii

Part III:

https://steemit.com/powerhousecreatives/@hlezama/folktales-racist-discourse-and-class-struggles-in-afro-venezuelan-literature-part-iii

Conejo Cum-boto

Fuente

Fuente

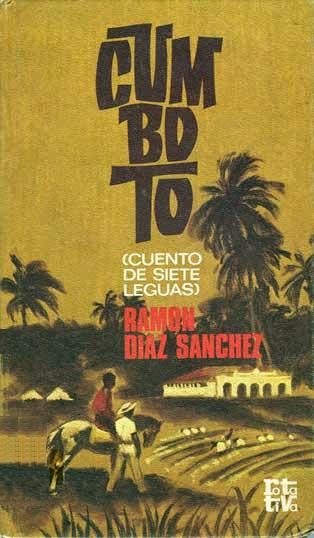

Cumboto, a plantation named after either an anecdote of runaway slaves from the Antilles who, when asked how they got to the Venezuelan shores, answered “cum-botos! cum-botos!” to mean “on boats” (Diaz Sanchez 10); or maybe it was named after the onomatopoeia of the sound of the drums. This town is the background of a story of three generations of Venezuelans and their search for identity. It is a story of a search for identity, broken idols, racial violence, and tragedies brought about by miscegenation, but also of hope. A more intimate narrative than Pobre Negro, Cumboto attempts to provide a vision of the black world from a black perspective with all its contradictions. The narrator, Natividad, is a house slave who, despite his domesticity and bleached character, confesses, “In my childhood and then, already a man, many times I felt the temptation of wandering through the forests, follow the river threads and get lost in the darkest part of the jungle, to discover the ancient refuges of those first blacks, dark dens where nature beats in the heart of the big drums; roads where you can still feel the coarse smell of the runaways” (10).

Fuente

Fuente

Natividad, whose origin is a mystery in the novel, grows up next to Federico, the son of the plantation owner. He gets acculturated from early age to the ways of the white masters; and, to a certain degree he would advance in the social scale, but he would still be reminded of his color and what it means in the social order. In one occasion, Natividad, who watched from prudent distance Federico’s piano lessons, sneaks in during a break to draw with Federico while Frau Berza, the governess, was absent. She heard Federico laughing at the “blue donkeys” Natividad had produced while trying to draw the leaves of a níspero tree. “This is not your place. Go clean the floor,” the governess told Natividad (16-17), and from that time on he understood that there were lines he was not supposed to cross. From then on, as the narrator says, his world turned black.

Fuente

Fuente

Like some narratives and novels by African-American authors, Cumboto may be read as a romantic or sentimental view of slavery. This is how Natividad describes Federico’s maternal grandfather: “[Don Lorenzo, whose will was law] admonished and punished the culprits, imposing on them even some corporal penalties that the laws of the republic had proscribed for being shameful, such as the lashing and the clamp. Despite this, the inhabitants of Cumboto respected don Lorenzo and obeyed him like a good father” (11). But, like any slave narrative and/or African-American novel, Cumboto also offers the complexities of the characters’ interactions and evolutions.

One of the first characters Natividad meets, who provides him with a vision of what being a Venezuelan black means, is Cervelion. “Us blacks ’av to know a thousand tricks to defend ourselfs,” he tells Natividad. “You is among whites, but you is black all over and them whites aren’t gonna teach you nothing they know; so, you ‘av to wise up if you wants to live like a man” (13). The other important character in the story is the Abuela Anita, who lives with her son, Ernesto, and his two kids, Pascua ad Prudencio. Pascua will become a key character in the novel. Natividad meets Abuela Anita along with Federico in one of their adventures to the river. The old lady always regrets that one of her sons left her because “he married a white gal to improve the race, I reckon” (28). This octogenarian ex-slave lady would become Natividad’s source of history, both white and black. In a chest Anita keeps a museum of artifacts, each piece telling a story and clarifying mysteries.

Fuente

Fuente

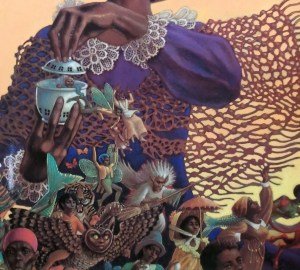

The story of Cumboto unravels when Federico’s father kills Cruz Maria, Cervelion’s son, for having an affair with Frau Berza, the governess. To compensate him for his loss, Don Guillermo sends Natividad to live with Cervelion. It is at Cervelion’s that Natividad will have his most disturbing encounters with black culture. One of these events is the brujeria Cervelion, his brother Roso, Venancio el pajarero, and other friends, will practice against Don Guillermo. This supernatural event, it is made to believe, causes the death of Federico’s father some days after he killed Cruz Maria. Federico is sent to Europe with his sister and this situation forces Natividad to get more immersed in the culture he had, thus far, rejected.

Fuente

Fuente

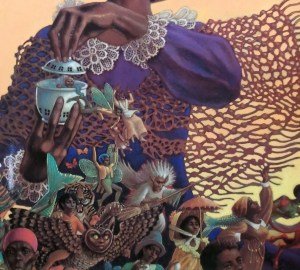

During this time, Natividad tries to rationalize the stories he is told and the things he sees in the black community. On the one hand there is Abuela Anita telling her stories of black and white devils and apparitions:

Grandma Anita ignored the civilized world of fairy legends where the princes marry shepherdess after rescuing from the spells of some perverse witch, the more so that literature where refined beings such as the Little Red Riding Hood, Snow White or Robinson Crusoe live. Hers were real stories, facts about which she could swear on her life, manifestations of a universe that was not less real just because it was beyond what is perceptible in the universe we move around every day. (31).

Thus, despite his incredulity, influenced by his years under the white master’s roof, Natividad allows this alternative vision of the world to exist and nurture him, even if he was not to become active participant of it. “Grandma possessed a whole theory of the preternatural, a primitive, simplistic theory, but not less defined nonetheless” (32).

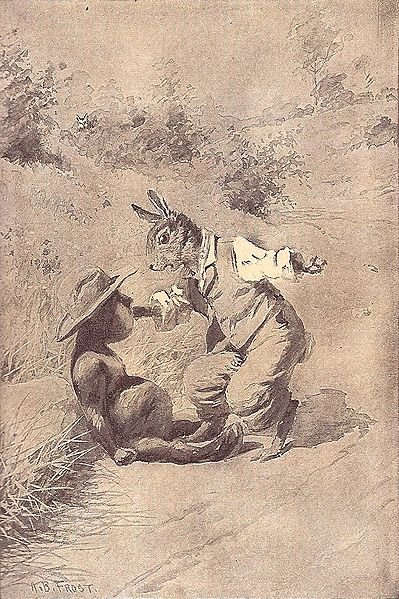

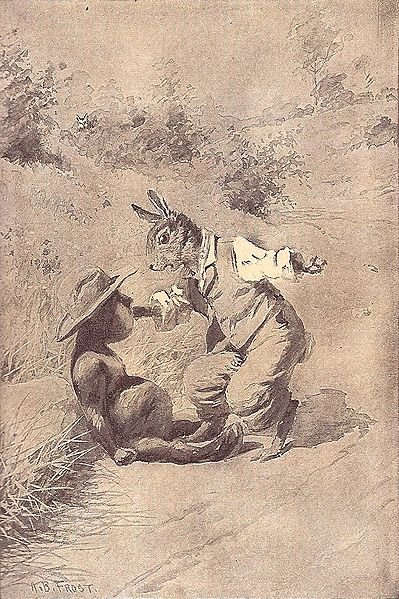

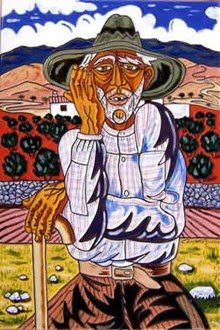

On the other hand, there was Venancio el pajarero, a consummated storyteller, yet an enigmatic character, capable of wicked actions. Although Venacio “knew all kinds of stories,” the trickster tales were an important part of his repertoire. “The exploits of Tío Conejo and Tío Tigre were endless and he knew them all;” he also knew and told Pedro Rimales stories (also known as Rimal or Grimales). Venancio tells the story of how Pedro Rimales got to stay in heaven by making God laugh. What causes God’s laughter is Rimales’ ability to trick St. Peter. Rimales incited St Peter to take his place in the gates of heaven where he got stuck and was being stung by bees. He told St Peter that it was a cosquilla he was feeling. Fool St Peter, of course, demanded Rimales’ place and got so pricked God could not stop laughing. “This sort of stories and those where Tío Conejo fools Tío Tigre and leads him, through very ingenious tricks, to smash his own testicles or flay himself alive, made the blacks laugh” (53). In Cumboto, a world of superstitions, death, fear, apparitions, etc., the trickster tales are meant to entertain, to produce laughter.

Fuente

Fuente

But Venancio, we learn later, is also an ex-maroon, an ex-rebel, an ex-guerrilla fighter. When Roso, shows up, Venacio, who is close friends of Roso, changes his tales of laughter for tales of war. “They did not talk anymore about lost souls or Pedro Grimales and Tío Conejo, but about a big and harsh war where the two friends had participated” (54). Natividad recounts then a catalogue of the atrocities Roso and Venancio committed during the Federal War. “What a bad devil was this negro Roso, that even became a sargent none other than in the personal guard of general Zamora. What a possessed negro, damn it! When the blond Zamora assaulted El Palito and defeated there the brave coronel Pinto, almost all the negros that accompanied him were from this coast.” This, in conjunction with his previous description of black culture, always in relation to white culture, makes the overall perception of his race problematic. “I wasn’t a very good soldier,” added Venacio, “why would I deny it? But I had to toughen up, like everybody else. When I drank that spirit withgun powder they gave us before every battle, I became a devil. And I made the most of it...looting...patateo...” (55-56). Patatear, clarifies the narrator, meant to chase the women, to look for them in the rooms; to get them out from under the beds, from inside the closets; to sever them from the altars in front of which they prayed, snatching them off their mothers to possess them one after the other. Honest as this depiction may be, in Diaz Sanchez’s world the black devils seem to be the “baddest” of all (56). Limited as the narrator’s vision is, this story lacks the socio-political complexities of Gallegos’ Pobre Negro.

Fuente

Fuente

At the end of the story, Federico returns from Europe and treats Natividad with indifference. Natividad becomes his shadow anyway, as he himself describes it, and witness how Federico falls pray of Pascua’s charms (now a beautiful woman). They have a tortuous romance, but she is forced to leave and Federico never sees her again. Federico later learns that Cruz Maria was actually his half-brother, the fruit of Dona Beatriz’s illegitimate romance with her mulatto piano teacher. At the end of the story a familiar-looking young visitor arrives at Federico’s. Natividad, now an old man and still Federico’s shadow, proudly witnesses the union of father and son at the piano; the former playing the classics, the latter improvising some African tunes; the musical mestizaje suggesting Venezuela’s ultimately destiny; yet, one that, unlike the Tío Conejo stories, does not make many people laugh.

To be continued…

Thanks for your visit

Visítanos en: www.equipocardumen.com.ve

Visítanos en: www.equipocardumen.com.ve

Fuente

Fuente

Fuente

Fuente Fuente

Fuente

Una vez más paisano dejando muy en alto el orgullo patrio, excelente continuación del ciclo de post dedicados a la literatura venezolana, muy bien documentados, magistralmente narrados... Tremendo trabajo, siga adelante. Saludos hermano @hlezama

Muchas gracias, hermano. Complacido con tus comentarios y tu lectura. Estas historias se están perdiendo sin audiencia. Creoque una de las cosas que se debe hacer si se da un proceso de reconstrucción nacional, es incentivar la lectura de nuestra literatura y devolverle a la novela venezolana su sitial de honor en los colegios.

Nuestros muchachos deben conocer estas obras para el momento que dejen los liceos, pero más importante aun, deben haberlas estudiando con profesores que amen la literatura, que sean lectores y sepan que hacer y como guiar a los muchachos a sacar el mayor provecho de esos textos.

Mas de acuerdo contigo no puedo estar @hlezama, el rescate de nuestra querida patria debe darse desde nuestros valores mismos como sociedad, rescatar nuestra literatura, nuestros maestros y el amor por el desarrollo intelectual, a veces leo algunos de nuestros periódicos llenos de titulares amarillistas de lenguaje que mas que coloquial raya en lo burdo y lo chabacano y me entristese no poderles decir a mis hijos, tal como decian a mi... Si quieres aprender a escribir y hablar bien lee el periodico... Que perdida de valores hemos sufrido!

Me hiciste recordar muchas cosas de mi niñez. Yo crecí viendo a mi papá (que era guardia nacional) y a mis hermanos mayores leer LOS periodicos. Cuando estaba en 5to año solia comprar unos 4 periodicos distintos. Durante mis años en la universidad hacia lo mismo.

Muchos de mis compañero me criticaban, sobre todo los domingos, cuando los periodicos venian más gruesos, traían suplementos especiales y revistas.

Yo sentía mi deber como ciudadano y futuro profesional estar bien informado y pulir escritura y lectura de la mano de los que mejor manejaban el lenguaje: nuestros periodistas.

Ahora cuando me paseo por los antiguos kioskos o esquinas calientes y veo solo últimas noticias (un panfleto delo último), junto a una que otra revista hípica, me siento atrapado en una de mis peores pesadillas.

Creo que podrías hacer un post sobre el tema de los (no) periodicos venezolanos y el lenguaje.

Yo tengo tiempo planeando varios post sobre la ausencia de estos en las calless y en las manos de la gente.

Thanks for teaching me some things about Venezuelan culture and history. I also learned some new words, like conejo is rabbit and mestizaje is mixture. I hope you are able to continue posting great content like this, as it is really an asset to the Steem blockchain!

a. Great. I'm glad you found the post informative and educational. That's always my goal.

Always welcome over here.

Dear @hlezama,

I enjoyed the story. I enjoyed the pictures!

I'm glad you did. Thanks for stopping by

A look into a world I've never considered. I'll have to read the book if I can find it in English. I love the art you chose for this post!

Thank you.

I am glad I was able to introduce you to this worldview.

I think there must be a translation of Cumboto. But this i the kind of book that went out of print sme time ago and must be very hard to find.

Even our most renowned authors (Arturo Uslar Pietri and Rómulo Gallegos) are hard to find in translation.

Please, let me know if you do find an english translation. It will be good to know.

I was planning to start a series of post on translations of some latin american authors short stories.

I would be very interested in that series. I can think of several others who would be too. Much needed! We have little more than our very biased news to know you by.

That's good to know. I'll be working on it

Hi @hlezama!

Your post was upvoted by @steem-ua, new Steem dApp, using UserAuthority for algorithmic post curation!

Your UA account score is currently 3.232 which ranks you at #8084 across all Steem accounts.

Your rank has improved 5 places in the last three days (old rank 8089).

In our last Algorithmic Curation Round, consisting of 208 contributions, your post is ranked at #110.

Evaluation of your UA score:

Feel free to join our @steem-ua Discord server