Folktales, Racist Discourse, and Class Struggles in Afro-Venezuelan Literature. Part III

Fuente

Fuente

Greetings, everybody

Thanks for accompanying us in the development of this topic. Let us now take a look at how the folktale characters are used in every one of the novels mentioned in the previous posts.

You can check the previous publications in the following links:

Part I:

https://steemit.com/powerhousecreatives/@hlezama/folktales-race-and-class-struggles-in-afro-venezuelan-literature

Part II:

https://steemit.com/powerhousecreatives/@hlezama/folktales-racist-discourse-and-class-struggles-in-afro-venezuelan-literature-part-ii

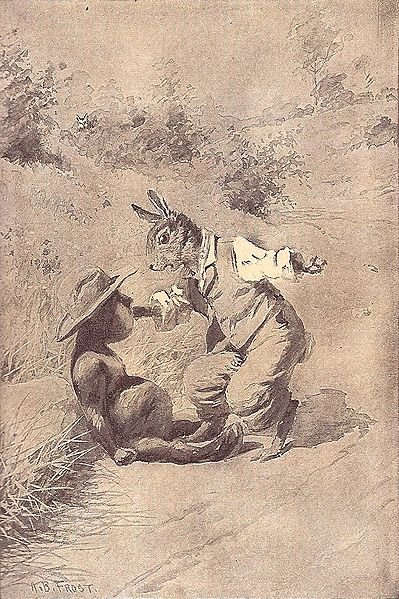

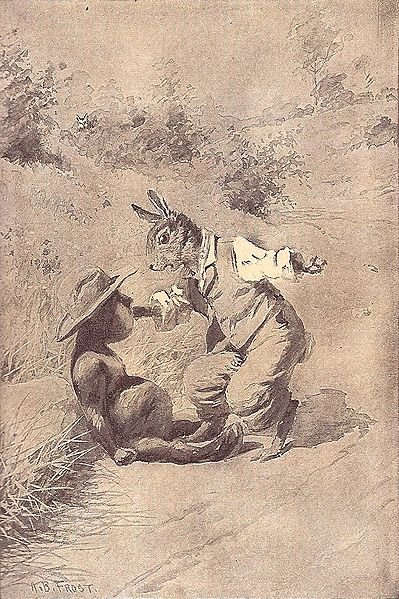

Pobre Conejo Negro

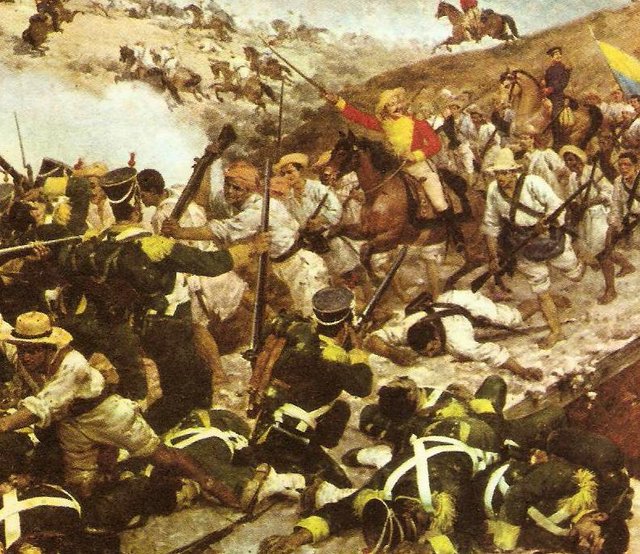

In a nutshell, Pobre Negro tells the story of three main characters: Pedro Miguel, Luisana, and Cecilio the young (to differentiate him from Cecilio Céspedes, his intellectual uncle whose role in the novel is also important), who branch out from the story of the Alcorta family. Don Carlos and Doña Agueda Alcorta have two children, Ana Julia and Fermín. Fermín marries one of the Céspedes daughters and has four children (Luisana and Cecilio the young being two of them). His sister Ana Julia is a sickly child who at early age is traumatized by witnessing the lynching of a Negro who had allegedly raped a white woman. Later in life, in one of her trances, Ana Julia strays and is found (half unconscious) by Negro Malo, a slave who had escaped his plantation to attend a baile de tambor. Negro Malo rapes Ana Julia; she gets pregnant and dies giving birth to Pedro Miguel, who will be raised by José Trinidad Gomárez, the capatáz of one of the fundaciones of the Alcortas. Pedro Miguel grows up ignoring his real parentage, he believes himself a black, yet falls in love with his cousin Luisana. His cousin, Cecilio tells him the truth and, as the Federal War erupts, Pedro Miguel rebels against the conservative whites, joining the federal army, which advertised itself as the champion of the dispossessed. Betrayed by his own men and disappointed by the war’s horrors and triscksterish purposes, Pedro Miguel deserts the army and flees with Luisana.

Fuente

Fuente

The novel, however, is far from being a love story. If anything, it may be considered a tragedy. But for Gallegos tragedy does not come from miscegenation itself, but from the dominant classes’ resistance to accept it as a consummated act, and their fears of the Other. Most critics treat Pobre Negro as a “social novel,” with all its cultural and political innuendoes. A mestizo himself, Gallegos seems to advocate a non violent resolution to the racial disputes, the avoidance of military confrontations, and the acceptance that, as a mestizo nation, Venezuela can also achieve prosperity.

Fuente

Fuente

The use of language, from the perspective of the black characters, is one of the most compelling ways in which Gallegos makes his statements. One of the first racial slurs we read in the novel is actually addressed to a snake; yet the implications of such slurs are easy to tie to the overall racial dynamic among the characters. When Negro Malo runs into a snake that seems to want to attack him to protect her lair, “he chops its head off in one blow and by the color of the poisonous snake and what boils inside his chest, retorts: no wonder you were Zamba!” (Gallegos 18 ). The commentary has to do with the fact that as a rebellious black slave, Negro Malo hated to follow orders from his zambo overseer, Mindonga.

Fuente

Fuente

This animosity among non-white groups reflects how influential the essentialist narratives regarding race had been. “Venezuelans and foreigners alike believed the worst of this mixture of Indian and African” (Wright 47). French traveler Jean Joseph Dauxion-Lavaysse [(1780s)] commented that in Caracas and surrounding areas ‘the word Zambo is synonymous with worthless, idler, liar, impious, thief, villain, assassin, etc.’ (in Wright 23-24). 80% of crimes were said to be committed by zambos. During the Federal War, [Jean Joseph Dauxion-Lavaysse] concluded, the zambos had proven ‘the most cruel and blood-thirsty of all troops, neither taking nor giving quarter, and have fairly outrivaled, in that respect, the Llaneros, or men of the plains’ (in Wright 47). Zambo, then, becomes more than a color tonality with which objects and beings (other than zambo people) are described; it becomes a term loaded with racial and essentialist assumptions that get attached as inherent qualities of the objects being described.

The slaves in Gallegos novel are more informed and aware of their reality than the masters think. They question their masters’ dishonesty by not fulfilling emancipatory laws proposed since 1821, for instance. “And then they don’t want shit to happen! (Gallegos 20), one of them sentences. There are, then, various kinds of animosities among slaves (against some of their own kind, against their masters, and eventually against all those, who, although not harming them directly, benefited from their exploitation and did nothing to stop the humiliating and inhumane system) and it is in the context of these animosities that the Tío Conejo stories are used to gain sympathizers for a political cause that is supposed to solve the racial and class differences. The storyteller in charge to perform the trickster tales is Padre Rosendo Mediavilla, a sympathizer of the liberal party, whose faenas (or corn catechesis, as he called them) had become one of the few joyous events in the life of the youth of Barlovento and Los Valles del Tuy.

Fuente

Fuente

In Padre Mediavilla’s stories naïve and oversimplifying binaries predominate. Tío Conejo and Tío Tigre share the stage; qualities, both animal and human are assigned accordingly: “cunning-strength; mockery-foolishness; humbleness-arrogance.” But then these qualities are extrapolated to the class structure of the time, “Tio Conejo sack shirt, Tio Tigre mantuano almost every night” (Gallegos 56). Of course, he tells these kinds of stories only to “the children of the people;” he does not, when he is with the “mantuanitos” or with the children of the grocer, the tailor, or the captain of a schooner (55-56). A shape-shifting trickster himself, Mediavilla had been criticized for his unorthodox preaching style, his irreverence, and his rather gross manners. The stories he tell, then, are in a way autobiographical and attempts to justify his methods of reaching out to his parishioners.

Mediavilla gives us the story of the time Tío Tigre became a priest. His young audience, familiar with the characters, immediately reacts to the absurdity of the situation. Mediavilla responds to the questioning, saying that Tío Tigre did it only because Tío Conejo was already a cura. And, of course, Tío Conejo was a humble priest who preached at a humble little church full of “little rabbits who got there bare-footed and wearing sack shirts” (56). One Sunday, Tío Tigre passed by Tío Conejo’s church and while Tío Conejo was in the sacristy he entered the church. He thought that if Tío Conejo had all those rabbits distracted despite his “ugly and vulgar chat,” as soon as he got on the pulpit and delivered a nice sermon as only he could speak, all the grass eaters would follow him to his cave and he would eat them.

Thus, Tío Tigre started to address the conejitos, but the initial reaction was of disbelief, “Eyes peeled, partner, not all that glitters is gold! That one looks like Tío Tigre,” voiced the rabbits (57). Mediavilla’s audience laughs out loud as they hear the characters in the story speaking “just the way they would.” But, continues Mediavilla, as Tío Tigre delivers some of those “beautified paragraphs, proper of the mantuanos,” the rabbits started to doze off, not out of enchantment, but out of boredom “for not understanding shit of the pretty sermon.” That would have not made much of a difference to prevent the tiger from eating them, anyway, had Tío Conejo not intervened on time. He wakes them up and leads them out of the church and away from Tío Tigre.

Fuente

Fuente

Young Pedro Miguel was in the audience and he wasn’t pleased by the story. He told the priest that he had been awakened time ago, not by Tío Conejo, but by the sharp claws of Tío Tigre himself (alluding to a scar left by the brutal punishment of a white man). This is a key incident in the novel. Pedro Miguel had developed a close relationship with Mediavilla, not missing any of his sermons and chores. But he was not interesting in the merriment as much as in the political discussions that came after the stories and customary reading of the counter-oligarch newspapers (58).

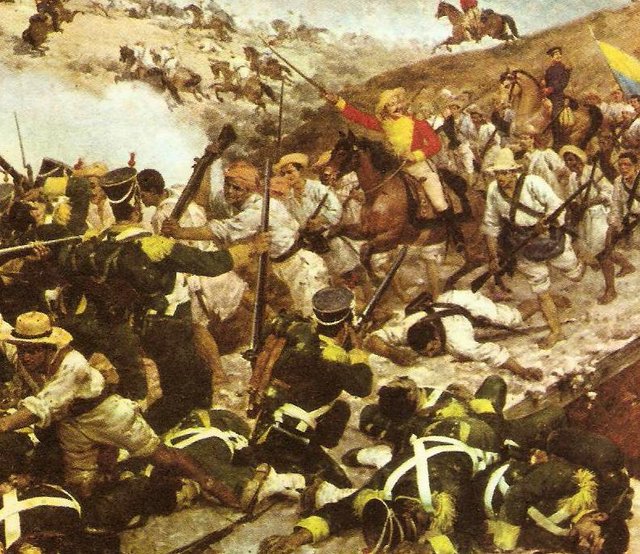

But, neither Tío Conejo nor Tío Tigre came out triumphant at this political moment. “The attempt at civilismo failed, General Páez’s caudillista tendency predominated and General Monagas ascended to power, thus losing the electoral undertaking both oligarchs and liberals” (76). José Tadeo Monagas would eventually become, in a way, responsible for the Federal War Pedro Miguel would participate in.

Fuente

Fuente

In the meantime, Padre Mediavilla would continue revolving the political arena. He met with sympathizers of different bands “and offered them the darkest coffee to excite their mood more than they already were have them fight among themselves, even of the same band” (140). Mediavilla’s chameleonic moves represent the complex alliances and counter alliances that characterized nineteenth century Venezuela’s politics (although the argument can be made that this is still the case).

Years later, when Pedro Miguel starts his wandering towards war, he finds padre Mediavilla in a small and impoverished town. When asked what he was doing there (having left his parish abandoned), the priest answers, “I came to preach at this church of Tio Conejo and here I am hearing the misdeed of Tio Tigre as told by these friends.” (151). He would later insist on convincing Pedro Miguel to become a leader of the dispossessed, “you have people, Pedro Miguel. See how all their eyes are on you” (152).

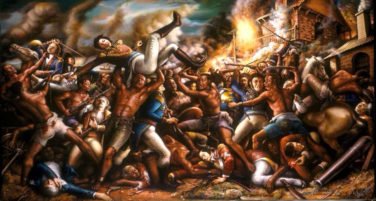

Pedro Miguel would eventually fight in the war and become a leader, but disappointment and tragedy would soon find him, and just like the tricked trickster, he and padre Mediavilla will learn the hard way what war really meant. Pedro Miguel meets Mapanare, another local leader, who had previously invited him to join the federal armies. Mapanare had picked up a demented padre Mediavilla, who, shocked by the horrors of the war and seriously injured on the head, had become a different kind of storyteller. Now he spun yarns without words, “while the paw-like hands waived in the air, the implausibly fine move of picking so subtle floating threads, with which he would spin an imaginary net...very subtle threads, maybe from the fabric of Christian women illusions that the war tore apart, right there, where the soul of the liberal priest was good-natured” (211-212).

Pedro Miguel would receive the

coup de grace by witnessing the treacherous assassination of Juan Coromoto, his best friend.

Of all the images of war that during four years had paraded before his eyes, spectator or actor of the tremendous scenes of slaughter and extermination, only one, as if fusing them all, did not leave his mind now: Juan Coromoto, the loyal companion who expected so much from him, collapsing from his horse, his hands reaching his back where he had received the mortal blow, because his fidelity hindered treason. And Juan Coromoto was not a man, but a por black man, which is a whole people, forsaken...” (232).

And abandon they had to, the land that once promised so much and delivered so little, in order to save Luisana’s life from the

armed parties that covered the coast, precisely to impede the escape the oligarch families that fled the town of Barlovento, where political pugnacity had overflowed the tempestuous tempers of class struggles,aggravated by racial inequality racial” (233 ).

Fuente

Fuente

Thanks for your visit

Visítanos en: www.equipocardumen.com.ve

Visítanos en: www.equipocardumen.com.ve

Fuente

Fuente

Fuente

Fuente Fuente

Fuente Fuente

Fuente

This set of articles is well thought out and presented - good research. Well written!

Thanks. Most appreciated

Interesting to learn some of the folktales from your region.

Something people are starting to debate, finding out more through stories told revealing a certain amount of history within the tales.

That's right. Stories do not exist in a vacuum.

Folklore studies (folkloristics)is a fascinating field. Even the analysis of jokes, riddles, or children's playground games provide interesting information about societies' history and their motivations behind the creation of all these cultural artifacts.

I'm glad you enjoy the post.

Thank you for your reading.

Excellent analysis of the racist influence in our literature friend @hlezama, is an excellent reading material, my congratulations for such a good job.

Thank you very much. I am glad you enjoyed it.

such a tough intellect historical write. Awesome, loved reading it

Thank you very much for stopping by. I am glad you enjoyed the post

We are SO proud to have you as a member of our

FANTABULOUS Power House Creatives family!

uvoted and/or resteemed!

❤ MWAH!!! ❤

#powerhousecreatives

Posted using Partiko Android

Thank you, guys