Classic Film Review — Nosferatu (1922)

What you're about to read could be better characterized as a historical analysis than a review. I examine the film against its place in history, culture, and the great canon of art and film.

Introduction

In 1919, after the end of World War I Germany replaced its imperial government with a representative democracy. At the risk of sounding like I'm giving the government any credit, I'd like to point out that this new Weimar Republic became a fertile ground for intellectual productivity which led to a flourishing of the arts and sciences.

This can be attributed to a number of causes including the chaotic social environment and passionate political landscape as well as the German faculties’ inclusion of prominent Jewish intellectuals beginning in 1918 (10). During this time period, there was an exponential increase in German film production. The most popular genre in the country at the time was the costumed drama, but the increase in financial success in the industry allowed a place for films of other genres. This was the time that German Expressionist filmmakers were able to make their mark on international cinema (9).

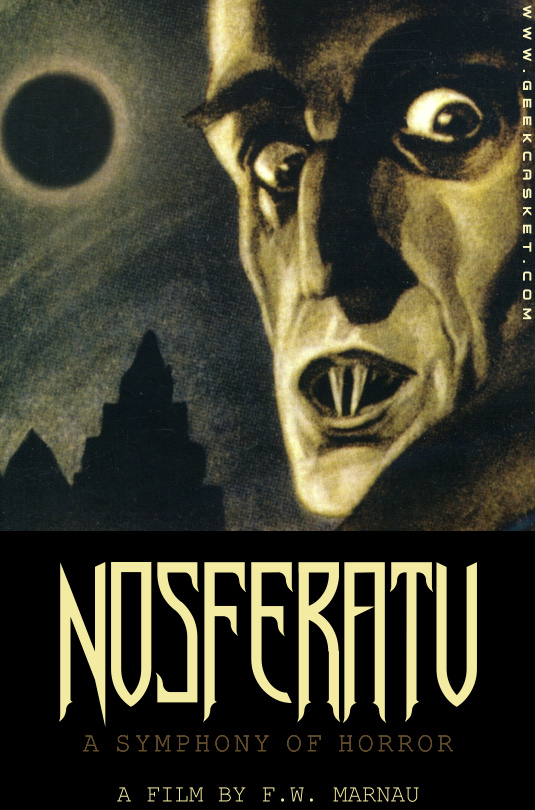

Among the most prominent entries into the German Expressionist genre is F.W. Murnau’s Nosferatu, eine Symphone des Grauens (translated A Symphony of Horror.)

Nosferatu, the first filmed adaptation of Bram Stoker’s Dracula (Perez), was a film born out of the environment of the Weimar Republic. This can be seen in a number of ways:

- On a practical level, one can connect the existence of the film to the increase in movie attendance in the Weimar Republic and to Germany finding its place in international cinema.

- One can also tie the film to the intellectual environment by looking at its openness to unconventional gender roles, specifically the role of women and its addressing of existential themes.

The Weimar Republic

Children playing with stacks of hyper-inflated currency.

The condition of the economy in the Weimar Republic led to an increase in movie attendance. Soon after the end of the war the German economy saw rapid inflation. But instead of addressing the economic problems, the government simply printed more banknotes to pay its bills (11). We all know how well that always works out, right?

Due to the out-of-control inflation, citizens of this time were quick to spend their money for fear that it would be worthless the following day. This new spend-and-enjoy mentality results in a vast increase in attendance at movie-houses (10).

As stated earlier, German Expressionism was not the most popular genre of the Weimar era, but the vast increase in film attendance gave financial incentive for the production of such films. Since German Expressionism was not the most popular, the film makers were forced to work with smaller budgets. The low budgets subsequently led to the style of this film genre.

The artists knew that on such a limited amount of money they could not hope to create realistic sets, so they ended up building off-kilter, stylized worlds. This is a testament to the creative power of artists who work with so little to create so much (10).

A set from The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920)

These geometrically absurd sets were painted with designs that are meant to represent objects, lights and shadows. The filmmakers would then have the actors mirror the extreme nature of the sets by distorting their expressions to reveal an inner emotional reality (9).

Nosferatu stands apart from some of the other Expressionist films since it was shot mostly on location. However, it still contains a dramatic use of light and shadow to make up for its lack of a lavish budget.

Murnau also utilized another staple of German Expressionism: the extreme performances of Max Schreck, Greta Schröder and Gustave von Wangenheim. Many of the features of Expressionist cinema that would later become so influential on American filmmaking might not have ever occurred to such an extent were it not for the financial instability of the Weimar Republic.

The environment of the Weimar Republic allowed the German film industry to find its place in international cinema. Before the end of the war, the German government banned many foreign films so that its own film industry could be more successful (thanks government!) But under the Weimar Republic, the ban was lifted which allowed for more international influences on German cinema (9).

One can see the influence of early Swedish films on Murnau’s style from his use of landscape and open air. More significant was D.W. Griffith’s impact on Murnau’s approach to cinema. Some might argue that Murnau was not a filmmaker of the cut like Griffith or Sergei Eisenstein, but rather a filmmaker of the moving camera. This is only a half truth. Murnau did often favour the use of a moving camera rather than a cut, but one cannot ignore his masterful Griffith-inspired cross-cutting in Nosferatu (8).

In one sequence in the film, the character Ellen Hutter, portrayed by Greta Schröder waits for the return of her husband. Murnau cuts between the parallel action of two waters: the wake of the ship in which the vampire travels and the waters of a stream that Hutter crosses. After more than a few cuts back and forth, the shots build up to an arresting point when Mrs. Hutter exclaims, “He’s coming. I must go to meet him” (4).

Because of the way he cut the film, the wife could either be referring to her husband, or perhaps through some supernatural connection she is awaiting the arrival of the vampire. This may not seem like a big deal to modern audiences, but in 1922 this kind of editing was not often seen.

Murnau continues this cutting later on as he jumps between the couple’s embrace at their reunion and the approach of the vampire. This crosscutting keeps the feeling of peril present even at what should be a happy moment (8).

Not only did German film of the 1920s find inspiration from international cinema, but German cinema itself began to have a global impact as the movies gain appreciation on an international level (9). This new international audience saw and ultimately saved Nosferatu from its demise after Bram Stoker’s widow sued the film for being an unlawful adaptation of her husband’s famous novel Dracula. She won her court case and all copies of the film were supposed to be destroyed, but since the movie had reached an audience spread across the globe, many copies of F.W. Murnau’s film were saved (thankfully!) (1)(3)(5).

As stated above, Weimar Germany’s act of opening its doors to international cinema was a major factor that influenced Murnau’s editing choices in Nosferatu. Germany’s new place in international cinema ultimately saved the film from complete destruction. Nosferatu is without-a-doubt, a film born out of (and saved by) the culture of Weimar Germany.

Gender & Existentialism

The 1920s Weimar culture also influenced German film, including Nosferatu, on an intellectual level. Nosferatu reveals an openness to unconventional gender roles. This is partly because as many as two million young German men had been killed at war, and German women were consequently pushed into a much more prominent position in German life.

It wasn't only practical reasons that caused a shift in gender roles; the Weimar culture brought about a willingness to experiment with bold new ideas and ways of life (9). Some argue that the story of the original Dracula novel is really a struggle over the contested realm of the female body. Professor Van Helsing represents the ‘good patriarchal figure’ while Dracula is the personification of wicked sexuality. Van Helsing would defeat the beast and return the feminine body to its ‘normal’ function of marriage and child-bearing. Dracula is a story that revealed a culture’s fears about sexuality.

A still from Bram Stoker's Dracula (1992)

F.W. Murnau and screenwriter Henrik Galeen decidde to take the story in a very different direction with Nosferatu. The Vampire, Count Orlok (so named to avoid a lawsuit with the Stoker estate... clearly it didn't work out) stands not for any sort of unholy sexuality, but for death itself (more about this in will be discussed shortly.)

In this story, none of victims of the vampire are women, at least none that are explicitly seen or even implied. Also in contrast to Dracula, a woman is the vampire’s main opponent and destroyer. Ellen Hutter makes the ultimate self-sacrifice when she offers herself to the vampire in order to keep him feeding until daybreak.

There are sexual undertones in the scene when Count Orlok is unable to resist Mrs. Hutter’s body and blood, but this is not the main point of the scene. The most important thing for the viewer to take away from this moment is Hutter’s self-actualization not as a sexual object, but as a fully formed, existentially authentic human being that gives her life to save those around her (8).

It is extremely unlikely that a film that addressed ideas like this could have come out of imperial Germany. Nosferatu liberated a woman from the all too common, not fully human role of a plot device. Ellen Hutter is a true human being and a bold representative of many of the ideas that were bursting forth from Weimar culture.

Weimar culture’s openness to bold new ideas (9) bred films like Nosferatu that addressed difficult philosophical themes. The most prominent philosophical theme in Nosferatu is, without-a-doubt, death. Some have called the film a response to the First World War: a response not to whatever authorities caused the war but to all of the death that ensued.

Murnau’s film is possibly one of the most resonant artistic essays crafted about the death that inescapably awaits every person (8). Unlike Dracula, the bodies of the victims of the vampire do not reanimate. The vampire kills, and the victims enter their eternal rest. Nothing more.

Having the victims rise again as vampires themselves would have contested the film’s existentialism. There is an extremely poignant finality to the great sleep that awaits the prey of this supernatural creature. The vampire represents death incarnate. He carries every person he encounters to his or her final doom.

For a film about a supernatural creature, there is surprisingly little room for any contesting supernatural force. From a great number of vampire tales audiences have learned to expect the symbol of the crucifix to serve as a vampire-repellant. The cross in Nosferatu only stands as a marker of death rather than a symbol of hope and salvation. The sort of religion that offers consolation for the dead and promises an afterlife has no place in a film that depicts the reign of mortality (8).

Nosferatu displays an incredibly bold vision, especially during a time when so many people had lost loved ones so recently. Murnau offers no consolation or condolences; he simply raises an awareness about the needless loss of so much life.

If the vampire represents death, then his victims are metaphors for different responses to death. The professor loses touch with the meaning of life and death since he only views it through a scientifically objective lens. Another example would be the shipmate who responds to death’s presence with total fear (8).

Conclusion

By now, the point that I've been driving at should be abundantly evident: Nosferatu is a film that is a direct result of the environment of Weimar culture. All the evidence examined above could cause a person to wonder what kinds of films may have come out of this republic were its life not cut short by the rise of a tyrant; a totalitarian ruler who tried to reign in the arts to serve him and the agenda of his party.

Perhaps nothing greater would have come of it, we'll never know. But no matter, today’s audiences still have a legacy of fascinating German films right at their fingertips that owe their existence to their culture, international influences and innovative artists.

~Seth

- Find out how I accidentally made a Great Experimental 16mm Film.

- Keep Calm and Ignore Blockfolio. ...at least for a few days.

- It's hard Watching Movies as an Anarchist.

- Anarcho-Memes now offers a $5 SBD reward for the best meme in the comments.

- I Made Three Curation Accounts for my Future Children.

- I'm about to Boost My SP Thanks to MinnowBooster!

- Presenting the Winner of a unique pencil-on-paper portrait, drawn by me.

- Watch this Music Video that I directed and animated.

- What Rights do you Actually Have?

- I'm creating a new animated series for Steemit called Steemit Explained.

SOURCES:

- Blankenship, Bill. "Lawsuit Couldn't Bury Early Vampire Film: TCJ Edition." Topeka Capital Journal (2002)

- Hall, Phil. "The Bootleg Files: Nosferatu." Film Threat. Hamster Stampede, 26 Oct. 2007.

- Hensley, Wayne E. "The Contribution of F.W. Murnau's Nosferatu to the Evolution of Dracula." Literature/Film Quarterly 30.1 (2002)

- Nosferatu, eine Symphone des Grauens. Dir. F.W. Murnau. Perf. Max Schreck, Gustav Von Wangenheim and Greta Schröder. Prana Film, 1922.

- Nosferatu Wiki

- Noseratu IMDb

- Patalas, Enno. "On the Way to Nosferatu." Film History 14.1 (2002)

- Perez, Gilberto. "Nosferatu." Raritan 13.1 (1993)

- Thompson, Kristin and Bordwell David. Film History: An Introduction, Third Edition. New York, NY: McGraw Hill, 2009.

- Weimar Culture Wiki

- Weimar Republic Wiki

Thank you for this excellent analysis, very insightful and well researched. I love German expressionism especially the work of Fritz Lang, Metropolis is one of my all time favorites.

Old is gold...

This is the second time you've reviewed an old favorite of mine and revealed a wealth of possible influence and interpretation which I had never before considered.

I can only conclude you are grossly undervalued ;)

Resteeming and submitting to @muxxybot :)

The Cabinet of Dr Caligari is a much better example of German Expressionism. The reason Hitler came to power was because of the decadence of the Jewish Intellectuals an unforeseen consequence of the Weimar Rep. Every perversity became commonplace and the people were sick of it. That coupled with crippling debt from the reparations of the Versailles Treaty broke Germany's economic back!

Thanks for your thoughtful comment. It's a matter of great shame that I haven't actually seen The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari... one day.

Enjoy... I've also included the German version (für alle Fälle)

Thanks :)

NP... I've done studies about how the liberal social policies of Weimar led to cultural decay... Hitler was the backlash. Also how the early cinematographers such as Murnau, Lang, et.al. influenced the later propaganda filmmakers like Riefenstahl. Murnau's use of light and shadow, particularly in Nosferatu was masterful. the technique was used brilliantly later to paint Jews and other "undesirables" in a negative light.

Fascinating!

Fascinating, and exhaustively researched. How have I not already followed you? That oversight has been corrected.

I usually don't do such thorough research for Steemit articles. But from time to time I'll go all out. In this case, I just adapted a paper I wrote for a film history class I took in university. Is that cheating? Too bad! It's done :)

I'm surprised I'm not already following you either. I know I've seen you around. I'm following you now.

Thanks for stopping by!

Anything you've written is fair game imo. I lean pretty hard on my stockpile of short stories I wrote over the past 5 years, for example. If it's new to Steemit, it's new enough.

I agree. A lot of my posts have been sharing old artwork and films that I've made.

Wow, such a well written post. I've always wanted to check out this movie. I actually read this twice. I'm really interested in seeing the movie sets that you discussed. I love watching old movies like this.

Loved it! Thanks for this wonderful interpretation :)

Old but not bad.. yeah

I quite agree that the replacement of independent art with state worship is yet another notable crime by Nazi Germany. Art cannot be legislated, and ought not be government-funded.

Somehow I've never seen Nosferatu, strange given I watched a bunch of old horror movies off a ranking sheet, will add it to my list. My favorite old-school horror is The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, a silent German film. The classics do an incredible amount with very little.

I'm embarrassed to admit that I've actually never seen The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari :(