Playing Out Of Order: Part 2 (Barriers

In our previous installment we talked about why you might want to use nonlinear narratives in games.

Today we're going to look at the problems that anyone will have to face while working on a nonlinear narrative in general and in gaming.

Getting Out of Order

One of the issues that comes up with nonlinear narratives is that they require a lot more work to follow. Heck, even linear storytelling can become confusing and complicated, so if you really want to do nonlinear play you need to be very careful with your storylines.

The big problem with this is that most people live life chronologically (if not all people, but I'm willing to assent to the notion that there are people who put relatively little interest in time versus significance of events).

The world is full of cause and effect, and pretty much everything we do with storytelling or even just basic skill processes comes out of an if-then relationship with the world. If someone goes on the Hero's Journey, then they will become a hero and improve their world. If I flip a switch, the lights will come on.

When something happens that is unexpected, it causes our brains to engage. This is not a bad thing. This is why we enjoy dramatic storytelling and humor.

Too much of a good thing, however, can be a problem. Jumping around in time is the advantage and fruit of nonlinear narrative: we get to have our brains challenged in ways that are difficult to replicate. However, shifting too much or with too much going on in the interim is going to have a major effect on audiences.

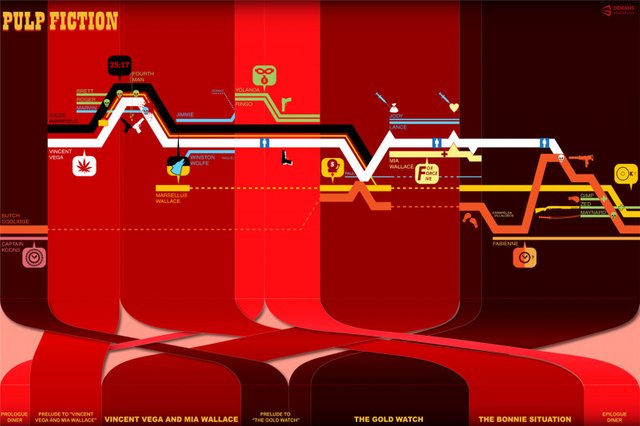

Let's borrow the Pulp Fiction diagram again.

One thing that is worthy of note is that Tarantino does is to unify his story into six main pieces (Diner, Vincent and Mia prelude, Vincent and Mia, Gold Watch prelude, Gold Watch, and the Bonnie Situation) and only a few of them actually follow the nonlinear structure. Two of these also serve to clarify other events.

Nullification

The biggest issue, however, is not that a story gets too complicated to follow. There are a number of methods for preventing this, from simplifying the story to providing recaps, and these can be done quite elegantly if needed. Audiences can also typically predict and fill in gaps quite well, to the point that shifting across time may require some retrospection on behalf of the audience but will not necessarily limit their enjoyment of a narrative.

Storytellers in interactive media (games) need to consider the fact that the events of a flash-back or flash-forward will potentially nullify other events due to the nature of nonlinear narrative. Although there can be gaps and omitted details without too much harm, anything that comes up that compromises a future event will derail the storyline.

The problem with this is that it can result in ex machina setups. Netflix's Bright, for instance, gives us a prophecy that manages to basically spoil the plot within the first few minutes of the film, and then leads us to a situation where it becomes clear that the writers chose to turn the story into a fulfillment of the prophecy, rather than building the prophecy to fulfill a narrative.

That happened with a central team of storytellers working to keep the narrative coherent.

In a game, you may find yourself in a situation where player agency demands multiple possible outcomes, and as a result your audience can easily nullify future events unless they are very important.

You can usually limit the impact of this by having vague flash-forwards to events that will unfold no matter what, but this goes back to the ex machina problem. Not every solution will be equally meaningful, so choosing a solution based on expedience is going to damage the narrative.

Stalling Out

If the story begins with a prophetic image of a main character dying, you can make that happen by any means necessary to fulfill it. Babylon AD, for instance, shows us Vin Diesel reflecting on death before having a series of events unfold to kill his character.

This death coming at the beginning is not the worst part of Babylon A, but it removes tension as the plot develops in exchange for a cheap hook at the beginning of the film.

When you use nonlinear narrative, you should consider the role that different times play in the importance and development of events. To go back to Pulp Fiction for a moment, it works so well precisely because each of the scenes has its own intrinsic interest outside of the whole narrative. Together they are incredible, but even by themselves they're important.

You want to make sure that you've fulfilled the narrative requirements to show the audience something before they jump into the scene that you're showing them as a storyteller. Going to the greatest, most dramatic event can be powerful to illustrate changes and development, but most of the time it will simply deplete the excitement of the moment and stall your momentum.

In honor of the recent release of Deadpool 2, which I haven't seen yet, I think this is a good time to talk about how Deadpool does this (on a very minor level) as well. The shift in time-frame following the opening sequence shows us who Deadpool/Wade Wilson is at the current moment in time, but then we are brought into his origin story and given reasons to care.

It also gives the directors a moment to really tell the audience what they're in for. Setting expectations early is important, and if you don't realize that Deadpool is going to be a very irreverent, very R-rated action-comedy by the end of the opening credits, you're probably incapacitated.

One of the issues that often occurs with time-shifting is that these expectations are never set up and the emotional payload of a story can't be delivered. Deadpool's example is relatively mild; his time-jumps are more akin to what you would expect of someone talking and launching into a side-point by going "Oh, but of course this has happened before that" and clarifying it to make sense.

With more extreme time-shifts, you wind up with a difficulty getting attachment. I think this is why I really didn't get into Cloud Atlas; I just didn't have any reason to care by the point that the filmmakers wanted me to care, so I continued to be apathetic about the plot of the film.

Some people will say that this simply means that an audience isn't sophisticated enough, but that's the equivalent of giving a motorcycle to someone who's requested a rental car and telling them that they're just not brave enough to ride the motorcycle. That may be the case, but it could also be that some malpractice has occurred and the audience has a reason to suspect the storyteller has made mistakes.

Because I aspire to earn a great deal of personal animosity by the end of the evening, I suspect this is the issue with Star Wars: The Last Jedi. Ambitious storytelling is necessary, but also requires a solid understanding of foundations and self-aware restraint.

Wrapping Up

Nonlinear narrative is not omnipotent. By subverting the traditional, storytellers have a great tool to really engage and challenge their audiences.

It also allows them to forget their own limitations and the limitations of their form. It is not difficult to make a plot too convoluted to follow (or to be fun to follow), too gimmicky and contrived, or simply stalled out. The traditional methods of storytelling allow the audience to find meaning through a variety of means, and moving too far away makes the storytelling process more difficult and potentially limits emotional and cathartic returns on the storyline.