Playing Out of Order: Part 1 (The Why)

One of the things I've been thinking about recently is how and why you might have scenes out of order in a roleplaying game. For some reason I've been stuck on Reservoir Dogs recently, because my gaming groups have, for whatever reason, all been talking about it at roughly the same time.

Skipping around time is powerful. It allows for a number of benefits and challenges at the table, and it gives a heck of a tool to let people really tell stories in interesting ways. It's also difficult. There are games that set out to try to do it, but I can't really think of any that made a lasting impact on me. I think that some of the problem with this is that it's not something with a good "mechanical" fix: it can happen under rules, but it's most effective as part of a planned narrative.

Nonetheless, it's worth considering. I don't have good "fixes" for how to put it into a game right now, but I do want to talk about why you would, what challenges would need to be faced, and some ideas of how to handle it.

Why Skip

Before we get into doing something, we should think about the why: otherwise we can waste a lot of time and effort doing things.

Setting up different timeframes as the window into the setting of a game universe is valuable in the right hands.

First, it gives players a chance to undo mistakes. For instance, everything could look like it's going wrong for the player characters, but then something happens that saves them.

Now, sometimes this is handled mechanically; you burn a Magic Token and it gives you the ability to just say "Oh, but we had a plan!"

This isn't awful, and it still rewards cleverness and lateral thinking. But it's not something that works well in large scale-solutions. A little deus ex machina in the form of "I had this in my pocket!" goes differently from "We'd already arranged for gangsters to show up and cause trouble down the street as we were starting the bank robbery."

If you want to maintain full agency, you can skip around, instead forcing the players to re-enact their planning and execution.

This has a few valuable effects, namely letting this be something that impacts current resources rather than requiring a Magic Token (so long as there is a positive remaining balance, you're just spending Schrödinger's cash/HP), and giving players a chance to show off what their characters are good at.

It also keeps the players from simply using an ex machina every time they get into trouble, because you force them to fix their own mistakes. The best part is that this still gives them the benefit, but reduces the rate at which such "cheesy" actions can occur, because the flashback is filling the gap between potentially catastrophic mistakes.

Another good reason to have these flashback sequences is that they can introduce characters and places, giving players a chance to set the basis for current and future relationships without just saying "Oh yeah, this guy is someone you helped back when..." and figuring out a hand-wave. That's not to say that this is too terrible: you don't want to flashback every time someone draws on a poorly defined contact, but it's also something that allows you to toss the players a bone without feeling like you're railroading them into mandatory success (alternatively, if you want a truly sadistic villain to feel justified, include them in a flashback where the players do something awful to them).

From a storyteller's perspective, you also want to be able to move around because it can let you fill in cracks. Jumping between events gives a chance to show important details that just don't exist.

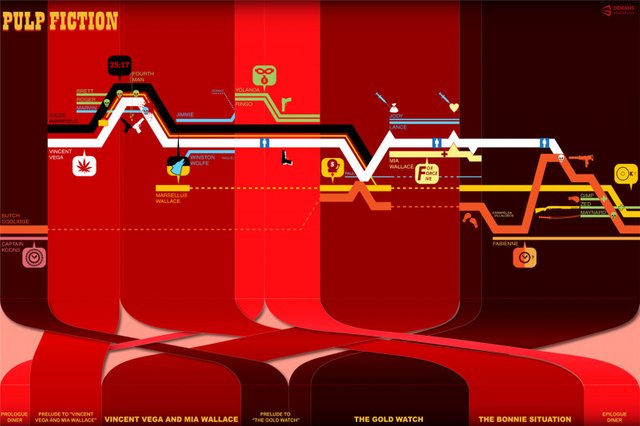

Plus, let's be honest: complex storytelling has a certain beauty to it. Case in point, see the illustrated timeline of Pulp Fiction below:

Who Does it Right?

So who does the time-skip in storytelling right?

Obviously Quentin Tarantino. I actually think this is his best skill, and otherwise his style would sometimes have issues and problems with being too straightforward. I won't go into a lot of detail about how he does his storytelling here, because either audiences are familiar with it or can study it on their own due to the massive saturation of work on the topic: other people have done it better than I would.

I remember being fairly impressed with Tribes: Vengeance in how it told its story, but I also remember being fairly young at the time and never getting it to run again, so take that with a grain of salt.

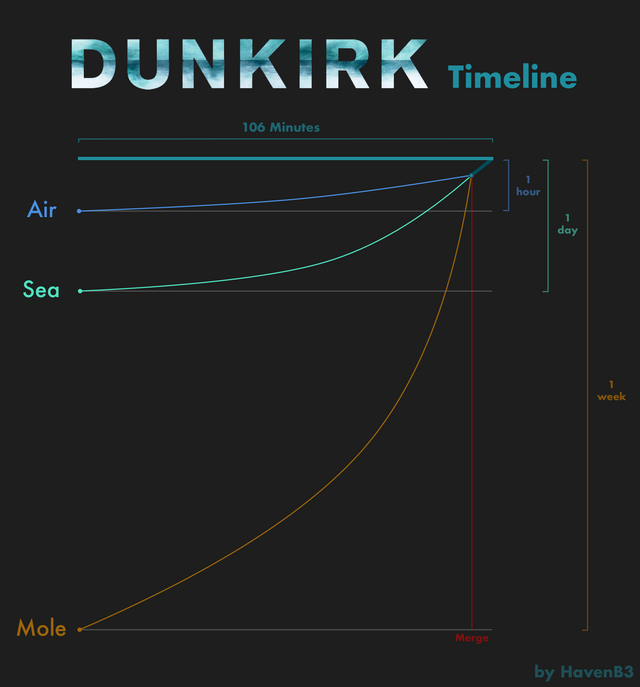

Dunkirk is a beautiful example as well, with a somewhat more simple timeline than Pulp Fiction, but one which is still very effective. By bringing three different angles on the fighting at Dunkirk, it manages to humanize its characters over the course of the movie without slowing down too much for an action-seeking audience.

I think this is actually a great use of the style in storytelling; where Quentin Tarantino uses it to build suspense, Christopher Nolan uses it for that purpose but also to keep the action flowing. It also allows for a sequence of events that makes sense together, even though there's some historical chronological difference between them (i.e. you would watch 99% of the movie before the RAF showed up, which would make the RAF characters entirely meaningless to the audience).

Dunkirk timeline by HavenB3 on Reddit

Cloud Atlas does this too, though instead of using the skips to build one set of characters it uses them to focus on a single theme and raise questions about things like reincarnation and the essence of the soul. By showing us a variety of different settings and points in time, we get to move beyond just following the characters and the plot and are forced to consider the point.

Writer's note: I actually didn't appreciate Cloud Atlas that much when I watched it (what is reading, anyway?) so I was rather disinterested at various points of the film. Forgive me if this is not an accurate portrayal of its contents; I remember some images and a handful of scenes, but pretty much nothing of any dialogue or characters.

Wrapping Up

There are a number of good reasons to use nonlinear narrative in games, but these can be divided into storytelling reasons and mechanical reasons.

From a purely narrative perspective we have three reasons: building suspense, introducing characters, and developing themes.

Mechanically, we want to do this because it gives us an opportunity to forgive failures and move the action forward.