A Conversation with Kafka — The Artist as Mystic

Franz Kafka’s blue octavo notebook aphorisms were first published in 1953, in the posthumous collection Preparations for a Country Wedding, under the heading “Reflections on Sin, Suffering, Hope, and the True Way.” That header, with its stair-stepping triplet of independent clauses—Sin! Suffering! Hope!--and its deft note of plea, was one of the innumerable publicity tweaks that Max Brod, zealous agent of Kafka’s literary estate, would perform on behalf of (or, some might say, in despite of) the spiritual reputation of his enigmatic friend.

It was Kafka who had culled the aphorisms initially from the pair of blue notebooks into which they had been handwritten. He transposed these, slightly editing some, onto consecutively numbered slips of paper he had arranged at his bedside.

Illness had set Kafka free. Tuberculosis had declared itself a month earlier when he first coughed up a little blood. Kafka would spend eight months, from September, 1917 to April, 1918, in Zurau, in the Bohemian countryside, at his sister Ottla’s house. In a letter from that time, Kafka compared himself to the "happy lover" who exclaims: "All the previous times were but illusions, only now do I truly love."

Of this letter, the scholar Roberto Calasso has written: “Illness was the final lover; which allowed him to close the old accounts.” Three days into his stay, Kafka scribbled: "You have the chance if ever there was one, to begin again. Don't waste it."

The sequence he produced was a first on many levels. It was, and would be, the only text in which Kafka directly confronted theological themes, and it marked the appearance, for him, of a new form.

#52 In the struggle between yourself and the world, hold the world’s coat.

#53 It is wrong to cheat, even if it is the world of its victory.

Calasso also wrote that, “Though Kafka made no surviving reference, either direct or indirect, to the existence of these aphorisms, one can't help but think that he meant to publish them in a form corresponding to the way he arranged them on those slips of paper." In Calasso’s edition of the now-fabled notebooks, the following aphorism, #109, concludes the aphorism sequence.

There is no need for you to leave the house. Stay at your table and listen. Don’t even listen, just wait. Don’t even wait, be completely quiet and alone. The world will offer itself to you to be unmasked; it can’t do otherwise; in raptures it will writhe before you .

Interestingly, this aphorism was one of eight that did not appear in either original notebooks. They were added by Kafka at a later time--possibly in 1920-- and were demarcated from the aphorisms that preceded them by a quick stroke of the pen.

What do you think is “the world” of which Kafka writes in Aphorism #109? What do you make of what seems to be the slightly eroticized imagery with which it concludes? Could one call this aphorism pure sublimation? Simply the dream of an impotent? Where does one draw the line in looking to literary figures for answers or sustenance?

Before anything else, “the world” of which Kafka writes in this aphorism is a present moment that he, as a creative artist, happens to be alive to and, with that present moment, alive, as well, to its present possibilities. I think, also, that “the world” of which Kafka writes in this aphorism is the ‘there-world’ into which he enters to write, as the yogis enter theirs to breathe. Do you know this story? Kafka has just written the most threadbare sentence possible, ‘He looked out the window,’ and having written such a sentence wrote immediately upon its heels, ‘I know that it is already perfect.’ Now, isn’t that striking? That this nest of neuroses, this terribly insecure man, could write—could know!—‘it is already perfect.’ From where did this uncharacteristic confidence come? This sounded note of surety?

During his encounters with ‘the world,’ Kafka is no longer quite himself and his hand is being steadied. Just recently, a poet friend shared some Buddhist teachings, and one of the fables I think comes very close to what I am trying to express. The sun is always out there, he said, but we walk around with clouds above us, with their cloud shadows upon us. If we can slip out from beneath those clouds or if we can stretch up our arms and muck those clouds about a bit, the sun will shine upon us. The sacred world wants to shine upon us.

But where is it, this ‘out there’? Where is it, this sacred ‘there-world’ to which we would go? I like the word interstice. A gap or a break in something generally continuous. A paradox, like the snake that swallows its own tail until it has swallowed itself entirely. A double-joint in time, or a space that is only a bit of fabric that gives, and one can just slip on through it. The interstate.

As a young reader, I envied the invalids. And the invalids spoke of their invalid status as enviable. Gibran and Proust, come to mind. Both were bed-ridden. Being bed-ridden was their permit to dream. It was a special dispensation, really, an exemption against engagement with the tedious responsibilities of the here-world. Invalidism gave them the license, and the luxury, to go ‘there’. To go and seek the twilight hour.

Some invalids are life-long. Kafka probably romanticized himself so. Turned his affliction into a badge of honor. Proust once wrote that the neurotics have given us everything. They are the ones who have saved the world, created the world, made the world worthwhile. Invalidism eased Kafka of the burden of himself. Eased him of the chattering fears that told him, ‘You must do better!’ That told him, “It will always be beyond your abilities, whatever you choose.”

I have been thinking, too, of fairy tales. The idea of Alice and the rabbit hole and its connection with physics. I don’t know much about physics. I’m just another artist-groupie, but I am captivated by the idea of a wormhole. A hypothetical tunnel connecting disparate points in light-space, with the attendant, hypothetical, possibility of time travel. None of this is encouraged by hard science, but neither is it entirely refuted. Disputed, more-like. This idea of a shortcut between worlds, which, for me, translates as a shortcut into creative space, where inspiration is able to move with more agility and vision to engage with more dexterity. The world down the rabbit hole. One moment you are in the here-world and the next you are in the there-world. But, how? That is the crazy part. How does one devise a way of getting there? Or at least how does one devise a way of not blocking oneself from getting there?

As a teenager I read The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe, the first volume in C.S. Lewis’s “Chronicles of Narnia.” Before, I had read only horror genre literature. The Lewis book worked for me brilliantly on the level of pure horror, and then it went much further. As a teenager, I wasn’t aware of Narnia’s sacramental undercurrents. Or that Lewis was a ‘Christian Apologist’ (as he has been dubbed) and Aslan a sacrificial Christ figure. None of that holy apparatus was relevant to me then, but it is relevant to me now. I return to the book both for scholarship and for Narnia. I like the idea of a closet, that eponymous ‘wardrobe’, through which the children can only sometimes gain access to Aslan, who is Narnia. I like how it shows that the wormhole experience cannot be forced. It loves to happen, perhaps, but its ways are inscrutable. One moment it is fur coats in a rickety wardrobe, but push a little harder, it becomes fir trees in a snowy forest, satyrs, fauns, and all possibilities.

I have a poem that describes something like this:

My hours are afraid of my days

mistrust placing their feet down

suspicious of finding a foothold

tick-tock they tip-toe self-consciously

My days are afraid of my years

never able to forget themselves

standing around as I try to sleep

shifting their weights, shuffling fears

In the interstices, it is timeless

unwound and happily unfound

there we slip through the sieve

between those immeasurable spaces.

That’s really where it all is. Between those immeasurable spaces. The crazy part is getting there.

The Repressed, Deviously, in Masquerade

Kafka wrote many poems, but he did not call them poems. There is no need for you to leave the house. Stay at your table and listen. Don’t even listen, just wait. Don’t even wait, be completely quiet and alone. The world will offer itself to you to be unmasked; it can’t do otherwise; in raptures it will writhe before you. This is an aphorism constructed of mystic stations. One might call it a prose fragment or bit of wandering mage come to roost. I myself have no objection to calling it a poem. But specifically it is an aphorism constructed of mystic stations. Like stations of the cross. When I read There is no need for you to leave the house. Stay at your table and listen, I think of Pascal’s precept, that all our difficulties arise our inability to sit quietly in a room, alone. That if one could be still enough, if one could endure one’s own company, if one could remain present. If only one could. If only. Kafka is addressing our tendency to flinch. We flinch, for self-preservation, when we are with ourselves too long, because it quickly becomes too much. The boredom, the suffering, the restlessness. Don’t even listen, just wait, he says. Then, immediately: Don’t even wait, be completely quiet and alone. He is a reluctant Messiah, our Franz. Distrustful of his own authority. He must immediately make qualifications, equivocate. He bids us ‘wait’. Then, backpedaling hurriedly, insists: Don’t even wait, be completely quiet and alone. Because even the most modest expectation might scare it (the ‘there-world’) away.

We sometimes strain for feeling as though sitting outside a foxhole with our guns, waiting for a fox. The fox never leaves. It will never leave. Because it knows it is being hunted. Watched-for. Expected.

Those lines, ‘The world will offer itself to you to be unmasked; it can’t do otherwise; in raptures it will writhe before you…’ bring me goose bumps and, yes, tears and, yes, I do think a sublimated eroticism is partly accountable for the charge, the zap. I think of Nietzsche, especially in Zarathustra, ‘the waves are heaving breasts,’ etc. That from a man who may have seen all of one pair throughout his adult life. In a letter to Milena, Kafka will write: To try and catch in one night, by black magic, hastily, heavily breathing, helpless, obsessed, to try and obtain by black magic what every day offers to open eyes!

Alas, poor Milena! Imagine being the recipient of such a letter, imagine being a young woman learning about her young man, and receiving such a letter. How could it not sting? And imagine being the one who had sent such a letter. Imagine being the young man. How can such a letter ever be lived down? It is too big to regret. It is Van Gogh’s ear. It is too much to take back. It is yesterday’s moon. Sometimes a voice out from the chaos of spirits cries and one finds oneself having written. Can one say that? Or perhaps it is only poetry. The young man, in fear of the young woman, writing of sack-cloth and ash, wishing his body would be burnt away. Nothing more to it. Whatever is dammed must find another outlet. Whoever is damned must find another heaven.

The Ecstatics from my tradition, the Persian tradition, could be wildly erotic, but because they were addressing themselves to God they felt safe. For Kafka, the mystic ritual he called ‘writing’ was his safe zone. Where he could let it all out and breathe light like a spirit fish swimming between stars. Mysticism is desire, like everything else is, and the desire of mysticism is a flaming arrow launched toward union. That union of the mystic, fire reaching to fire, no less than any carnal union, is an erotic experience. An ecstasy in the specifically Greek sense of ekstasis, meaning ‘outside oneself.’

Part of what we read in Kafka is too personal. Tedious neurasthenic considerations. Documents for the doctors at the Sanitarium of Hypochondria. The repressed, finding its way, surfacing, deviously, in masquerade. And part of what we read in Kafka is a universalized, lived, sensuality. Shy experience of the self as other. Veiled encounters with the beloved. Butt-naked tusslings. And why not? To get there means ‘union’, long longed-for (or, it may be, ‘reunion,’ long hoped for) and it induces bliss. The ‘impotent’ who eroticizes the world, for me, he is the prophet. And I’m not the only one who thinks this. Lawrence Durrell, in his novel Justine, writes, “the sick men, the solitaries, the prophets [!]…all who have been deeply wounded in their sex.” The statement lacks proportion, but there is truth in it. To be wounded in that way is to dam a furious river that begins, as Rilke tells us, ‘in the sky.’ ‘Making music is another way of making babies,’ writes Nietzsche. And yes that is sublimation and yes it does color thought, but doesn’t it color thought in wonderfully feverish flesh tones and isn’t all that fleshly frailty and failing a living part of Kafka’s meaning for us—a necessary aspect of its divinity? Isn’t all that partly its sacrament? And isn’t the chaos and aren’t the death-thralls just autumn leaves in their season?

Where does one draw the line in turning to these literary figures for answers or sustenance, or for that matter tips on elegant living? Where does Kafka end and literature begin? Would I read Kafka’s unpublished journals? Yes. Would I read Kafka’s laundry list? Yes. Where does one draw the line? At what he agreed not to burn? I am with Max Brod. Everything Kafka wrote (or for that matter said or did) is interesting because whatever he does, he is still doing the work. And the work is just self-work, but so, too, could be said of anything any of us do, in any capacity, fence-mending, love-making, book-binding, that it is just self-work. With Kafka we are given the opportunity to witness a self-work master-technician seeking, with elegant precision, his own hinterlands, focused in a state of such contained urgency, that it is almost a trance of clairvoyance . Kafka is us, without the lying.

Shouldn’t that change the way I read him? It should. And it does. It ups the volume on everything. Even if he only clears his throat, it rings like thunder. Because the fact of the matter is he has something thunderous in him to say, and the fact of the matter is we know that he does. That is the point. Some of this stuff, sure, it can be more navel gazing, more convolutions, but what we cannot fail to recognize in Kafka is that this is a guy who is wrestling with his angel, and that commands our attention. What he is up against, so are we up against.

In the two slender notebooks, those two blue octavo notebooks, meant for school-children, we get his private conversations. And in private conversations all of us tend to think more childishly, more innocently, more directly, about hope and suffering, good and evil. If Kafka were to have translated those private conversations into public fictions or such-like, something that could have been folded twice and shot skyward under cloak of literature, his style would have to have been necessarily more self-conscious, more ambiguous. But, because these were entirely private conversations, and because they were left so, they became perfect mirrors. Looking glasses. Beyond the fairy tale of the bardic. Verging on the estate of the vatic.

Listen, now: Aphorism #16: A cage went in search of a bird. That’s all of it. That’s all there is. No root. No soil. Bloomed in thin air. Sometimes from Kafka, we get a truth that just is. A white, as it were, flower lapel that is not worn in irony.

That cautionary reprobate Charles Baudelaire once wrote, “The greatest wile of the devil is to convince us that he does not exist.” This echoes many of Kafka’s octavo notebook aphorisms about the idea of evil. It’s almost the cleric or the choir boy in Kafka writing at such times. At another level, though, it is as if he is some august theologian, transmitting a soul-map in code.

© Yahia Lababidi

(Images: Pixabay)

This is really awesome writing Yahia and I mean that in the truest sense of the word. I very clearly remember my first encounter with Kafka. When I was 15 I took a 3 month solo trip to France, England and Ireland, staying with family friends. My parents somehow managed to convince my local high school to give me credit for a semester of studies for this trip, and as part of that I attended a few weeks of classes at various schools along the way. In the lakes district of England I attended classes at a school, the name of which and indeed the name of the town even I have forgotten, and I took a theater class as one of the offerings.

One assignment was to read the first section of The Metamorphosis, and then (without using words, for obvious reasons) re-enact Gregor's interactions with his family and coworker as a solo performance for the class.

I was mesmerized. What was this that I was reading? Needless to say I read the entire thing, I could not stop at the assigned first section nor even put the book down once until I had finished it.

I was very surprised when my British classmates did not share my enthusiasm for the assignment and subject matter. Could they not see the genius at work here?

No they could not. I thank the powers that be for giving me the gift of perception in sufficient quantity to recognize genius when I see it. The world is a richer place for the Kafkas and indeed the Lababidis putting words on paper.

Much love - Carl

You do me honor, Carl. Since my mid teens, I’ve viewed the literary life as one of service and intensification of consciousness. Kafka helped me to see better and for the sake of this heightened perception, I continue to sell all else cheap...

It means a lot to me to hear how this piece resonates with you & to learn how you too were marked by Kafka around the same time/stage that I was.

“A book must be the axe for the frozen sea within us” says Kafka. And I have tried to dedicate my life to creating such literature. Thanks, again, kindred spirit for this note of recognition. May you be seen/heard 🙇🏻

this is such a completely awesome piece of writing, I thoroughly enjoyed and gladly recommend it to any lover of words.

Hey, that's really encouraging to hear! I hope my blog posts continue to keep you good company :)

very nice writing Yahia, yesterday i was near the statue of Kafka in Prague, i have always liked kafka and his dark writings so your work is familiar to me, keep on the good work

Grateful you enjoyed it, Jacob. It’s funny, as a young man, I was drawn to Kafka for his darkness, as you put it — but with time I am mining him for light.. (visiting Prague was a sort of pilgrimage for me).

I hope my words continue to keep you good company 🙇🏻

Hello,

Post found helpful and informative to spreading the gospel on steemit and beyond. Resteemed.

This might be very helpful. Join the movement now.

Join the Discord Server for further information

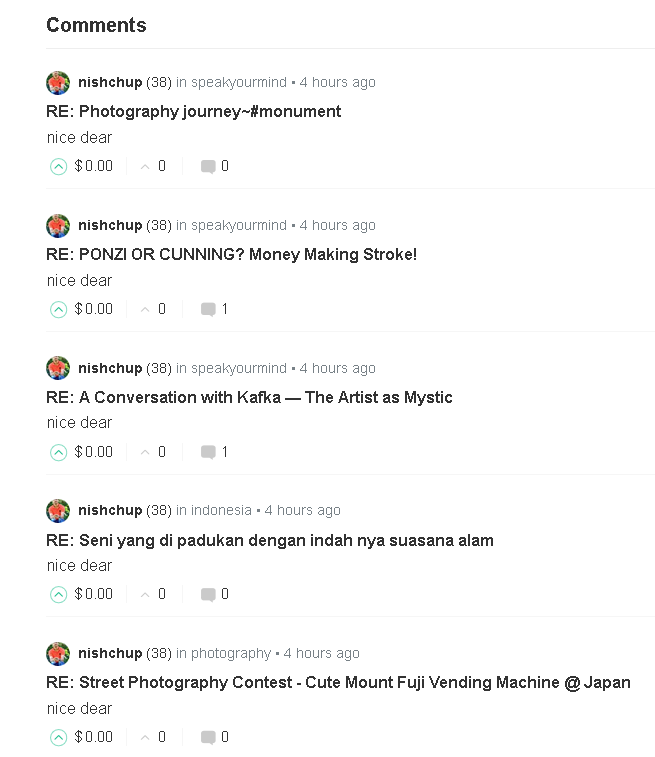

nice dear

Wow, you're a fast reader - I just posted it!

well presumably you already know this, but if not - the people who show up with a generic comment seconds after you post something are comment spammers. He did not read the post.

It did not occur to me think that, Carl. Pity...

Yes it is a true pity and a plague that threatens the long term survival of the platform. There are literal "comment farms" that churn out new accounts daily, all spamming automated comments such as this across the blockchain and relying on the naivete and goodwill of Steem users to toss them the occasional upvote, the proceeds from which all get funneled back to the comment farm operators. I gave this gentleman the flag he deserves for this. If only more users understood the gravity of spamming and the way the accumulating weight of spam threatens to pull us all under water... I know many people are hesitant to ever throw flags. But they exist for a purpose. This gentleman should not have a 38 REP and I am happy to do my small part to lower it.

Cheers - Carl

Mant thanks, for caring, man, and doing your part to help this community to thrive.