Dispelling the Myth of the "Sad Zoo Animal"

Keeping animals in captivity is a subject of great controversy, one with good arguments put forth from both sides. Many conservationists recognize zoos and aquariums as key elements in the continued survival of many animals species, while other animal enthusiasts prefer that animals live more natural lives free from captivity. We want to support the conservation efforts of these facilities, but it is hard to see exotic animals spending their life in confinement. So who is "right" here?

In one of my first posts, I discussed the importance of zoos and how these facilities are incredibly beneficial to animals, both species and individuals, despite their sometimes negative public reception. Zoos and aquariums are meant to conserve and protect animals at the species level, while also providing care and enhanced lives for their individual animals (no small task by the way!). A recent article was written that pointed out many of the misconceptions people have about animals residing in zoos, more specifically, their emotional welbeing. While most visitors who come to zoos are satisfied that the needs of the animals are being met and exceeded, many others still worry that these animals are suffering as a result of their captivity. You have probably heard these phrases at your local zoo, aquarium, circus or other animal facility.

"That bear looks sad."

"That lion is bored."

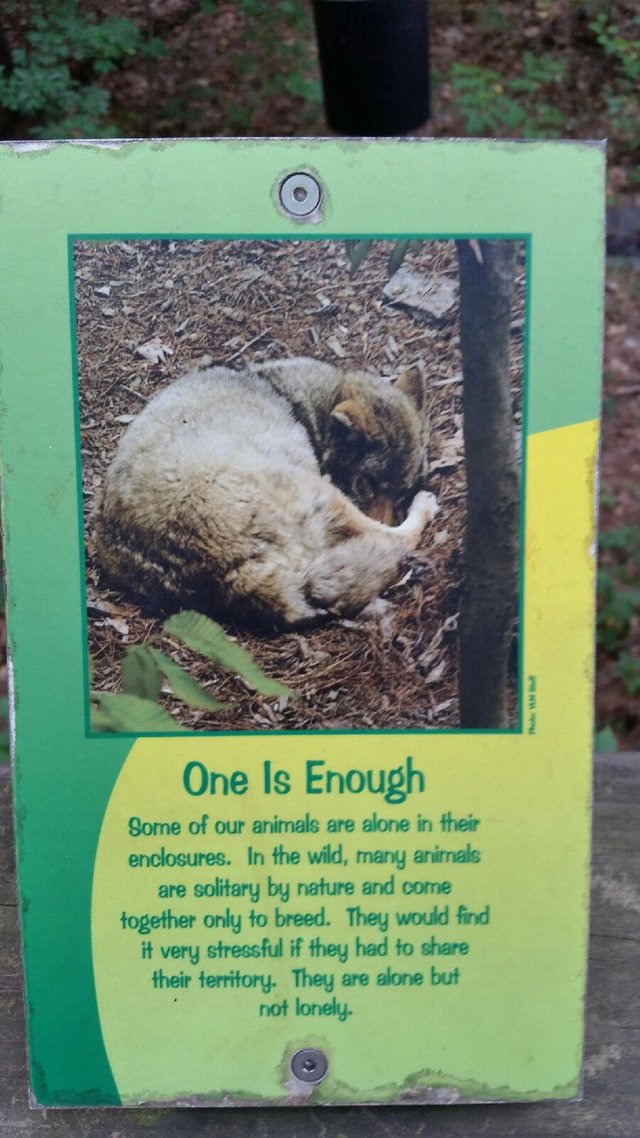

"That bobcat is lonely."

Many of these comments are a symptom of our need to anthropomorphize animals; essentially, we try to humanize them and their actions or emotions. People who don't spend much of their time around wild animals simply don't have the ability to determine an animal's mood (just like how people with cats can generally read a cats emotions while dog owners are better at reading canine emotional cues; it's all a matter of experience). There is a lot of variation between individuals and species, so it is very easy to misread an emotional cue without extensive experience.

Different species of animals behave very differently when they are scared or nervous. Take dogs for example; when upset, they typically bark or growl to display their displeasure, which we know how to recognize thanks to our experience. But some species are far more subtle in their emotional cues, displaying behaviors most people simply aren't trained to recognize or even mistaken for other emotions. A particular animal, like the author's spotted genet, may seem incredibly calm and relaxed, when in actuality it is scared out of its wits and prepared to defend itself. Other species, like some primates, appear happy and will even "smile", baring their teeth in a fashion that seems genuinely friendly, but to them means "back off".

Other species just look naturally sad. Their facial structure may simply result in giving them a sort of permanent frown, even when they are content, excited or happy. Some meaningless actions may give the impression that an animal is sad, while in reality it has no real bearing on their true emotional state. Imagine a dog once again; when tired, a dog may rest its head on its paws, sometimes giving them the appearance that they are sad or droopy. We know our pets aren't sad, it's just how they look when they do this; the same idea applies to many of the animals in the zoo. Alternatively, some animals just look naturally happy due to their facial structure; many snakes for example seem to have a permanent smile plastered on their face regardless of their current mood.

Animals in zoos often seem lethargic during our short visits. Part of this can be blamed on programs such as documentaries: while these programs are great for educational purposes (I definitely have nothing against them!), they tend to only show animals actively engaging in their activities such as hunting/foraging, swimming or playing. As a result, these are the behaviors people are expecting to see when they visit these facilities. In the wild, when humans encounter animals, they are likely more active and alert due to the human presence (they are less likely to be resting while a potentially dangerous human is near), but at zoos, these animals are 100% acclimated to the presence of people. They are less alert and more inclined to enjoy their downtime, which is just as important as their more engaging activities (this is a good thing!).

Boredom in zoos is something we do have to address as keepers. Animals can get bored in the wild but it's less common because the animal must focus on its own survival. In captivity, survival is a much less pressing issue (thanks to daily feedings and care) so boredom is actually considered a form of luxury (as long as there isn't too much boredom, which is addressed as a welfare issue). Keepers engage their animals in enrichment activities designed to stimulate them both physically and mentally and encourage their natural behaviors and skills.

Animals may be sad sometimes, but not necessarily due to their confinement. Some animals, just like people, have their good days and bad days and their moods may fluctuate. If an elderly animal passes away, some species (such as elephants) will mourn the loss for a short time. Other animals may face a short period of stress due to an environmental change, but this will dissipate with acclimation. When you see what you perceive to be a sad (or bored) animal at a zoo, keep in mind that they are likely not always in this state. It is harsh to judge the standards and care set forth by the zoo based on your short observations of an animal during one day's visit. Perhaps an animal is resting after eating a large meal; perhaps they are calming down from a stressful vet visit. Be careful not to project emotions such as loneliness onto the animals; some species are housed separately on purpose as they are solitary animals that might be stressed out by the presence of other individuals!

Cages and bars. Just the sight of them is enough to make us feel sorry for the animals, but here's the thing; these bars don't have nearly the same emotional impact on animals as they do on us. To us, bars are not just a barrier, they are a symbol of a loss of freedom, eternal confinement, lack of dignity, and are associated with criminality, among other things. But the animals at the zoo do not hold the evolved, cultural aversion to cage bars that we do; they simply see a physical barrier and have no emotional feelings toward the structure. While we much prefer to see animals living in enclosures with moats, natural stone walls or see-through glass, they simply view all as environmental barriers. For this reason, some zoos still use classic cages and bars to save money, allowing for greater features, care and more natural conditions within the exhibit itself.

So what is the takeaway from the article? Is it that everyone is wrong and it is not okay to judge a zoo exhibit? Absolutely not, it is perfectly okay to evaluate the welfare of an animal and it's enclosure...provided you take an informed approach. The public should absolutely be allowed and able to tell right from wrong and object to poor welfare when they see it (there are still facilities out there that do not provide great care standards and are facing public pressure), but this is a slippery slope. It is hard to judge welfare based on a short observation, especially with little knowledge of the animals' lifestyles, personal histories or behaviors. Talk to keepers and volunteers; they know these animals and will often be able to explain why an animal might be behaving unusually or seem moody. Keep in mind what you might not be able to see: what vet care is proved behind the scenes? Is it possible the animal has access to a larger area that you can't see (many zoos offer the opportunity for animals to have access to privacy)? And above all, avoid emotional projection; it is inherent nature to see ourselves in the animals. We have to be able to see things from the point of view of creatures that may be very different from ourselves.

Note: When I talk about zoos, I am typically referring to facilities that are accredited by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums or other reputable organizations with strict ethics, standards and regulations. These zoo provide the best care for captive animals thanks to routine inspections and protocol implementations. Some privately owned zoos exist that do not provide adequate care for their animals (hence why they are not accredited). In any facility, if you truly feel there is a welfare issue, contact a keeper (we want to know if there is an issue) or the facility's governing body.

Photo Links: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10

Article Link: http://hubpages.com/animals/sad-zoo-animals

Good article. Overall, I felt it was pretty balanced, despite your subjective standpoint as a zookeeper. Well done!

As a biologist, I tend to think of zoos as a necessary evil. In a perfect world, no animal would need human intervention to save it, and people would be able to emotionally connect with nature and wildlife without zoos acting as the medium. However, zoos are necessary for both of these results, and I often think that the second, fostering emotional connection with nature and wildlife, is the most important thing zoos do. The animals are important, of course, but if more people had compassionate attitudes to nature and wildlife fewer zoos would be necessary!

That said, I have great respect for zoos and zookeepers. I have many friends who are zookeepers, and know amazing zoo vets.

I do have two points to add. The first regards non-mammals. The death rate for, say, fishes, is exorbitantly high in zoos/aquariums. When an aquarium receives a shipment of fish, many if not most of them die. So I think there's something to the non-mammal vs. mammal issue that needs to be explored further.

The second point I'd like to make regards my specific field of biology, stress physiology. I wonder how frequently zoos measure their animals' stress hormones? It would be easy to do with non-mammals as well. The only problem is that it's not very cheap yet, although I know Disney does this fairly regularly with reproductive hormones (I applied for an internship measuring hormones with them).

By the way, there's a selfish part of me that, even in a perfect world, would still want zoos, because I want to see snow leopards! My local small zoo has one!

One last thing; thank you for pointing out the cognitive dissonance that nature documentaries cause. From a biological standpoint, a healthy animal is one that humans don't see; in other words, it is smart enough and capable of hiding, which is what most animals do most of their lives. So although it's great to see lions attack elephants at night, and it's astonishing to see the woolly bear caterpillar freeze solid every winter, most people don't realize this one truth: it's not natural to see most animals in the wild.

Wow, thank you so much for your comment!

I tried to keep the article as balanced as possible despite my obvious bias (:D), but I think that recognizing public opinions of our animals' health and welfare is part of being a zoo keeper. While we absolutely do want to believe our animals are always happy and healthy, we have to acknowledge that, despite our best efforts, this is not always the case. Addressing these welfare issues from the perspective of visitors not only reassures guests that the animals are receiving proper care, but allows us to more accurately gauge how the animals are really faring in captivity (just like how guests could misjudge something during their short visit, we occasionally miss something important because we are working behind the scenes or with other animals).

I absolutely agree with you; zoos are not, nor should ever be considered the ideal situation for an animal. And most zoo keepers and aquarists would agree as well; we would much rather see our animals living their lives wild and free. One of the things I love most about my facility is that we don't take in healthy wild animals (if injured, we may treat them but they are released if possible). We only accept animals that cannot survive on their own in the wild (injuries, orphans, imprinted on humans, etc) or cannot legally be released (born in captivity or considered a "nuisance" animal). For most of these animals, if we were unable to take them, they would have to be put down. Our facility provides a home for these critters and uses them as "ambassador animals", connecting people to their local wildlife. Some of our animals, like our Red Wolves, are so incredibly endangered that they are actually owned by the federal government, but are simply housed at the facility to be cared for by trained keepers and vet staff.

The fish scenario is a good point, but I think this is changing for the better. Many facilities, especially aquariums, do experience high mortality rates due to keeping and shipping fish in huge numbers (less space, higher chance of disease, etc). Organizations like AZA are slowly changing the regulations for these animals. Our facility does have an aquariums department, but interestingly, our aquatic mortality rate is actually surprisingly low and we don't receive new animals very often. Part of this reason is that we house many species of fish individually, and some fish have entire tanks to themselves. Similarly, when shipping, we try to only have one or two animals packed in each shipping container, allowing for more room to swim and less chance of inducing stress or spreading disease. Hopefully, practices like this become more common.

More facilities are doing stress tests, looking at levels of corticosterone and other stress hormones. It's not incredibly common, and I admit my facility does not do it, but I think this is practiced by larger zoos, aquariums and organizations. At Disney for example, the animals are exposed to incredibly large groups year round and keepers (always super busy) cannot be expected to observe their animals all day long for the smallest signs of stress. Doing hormone stress tests is a reliable way to keep their welfare in check. Our facility is fairly small and our animals are definitely not exposed to the same level of activity, so we do not do these tests (like you mentioned, cost is a huge factor). Instead, we observe our animals for any signs and have volunteers constantly watching exhibits for any unusual behavior (odd movements, fasting, etc). It's not the ideal scenario, but hopefully something else that will change in the coming years as regulations and standards improve. Even just the last ten years have done amazing things for zoos and animal welfare so I think a lot of the remaining issues are going to disappear or be reduced dramatically.

Again, thank you so much for your comment! Good luck to your internship application; you'll definitely have to keep us updated (if your allowed to)!

Hi @herpetologyguy, I just stopped back to let you know your post was one of my favourite reads yesterday and I included it in my Steemit Ramble. You can read what I wrote about your post here.

Thanks for the comment and support! Glad you enjoyed the post!

You're very welcome .

Agreed. Anthropomorphizing creatures leads to bad decisions.

It's a hard thing not to do and I totally understand that. As I keeper I don't mind too much when people anthropomorphize animals because it means they care about their welfare...but it does lead to possibly uninformed opinions. You just have to find the right balance!

Found this video of a gorilla dancing in a pool.

https://steemit.com/steemit/@rodneyaspiras/dancing-gorilla-in-pool-goes-viral