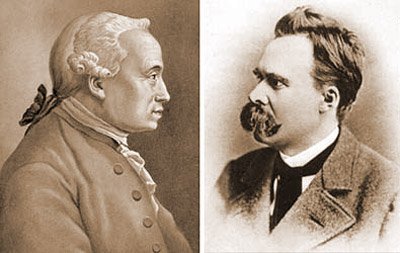

Philosophy Talk: Kant and Nietzsche, a philosophy of Authenticity

The following research seeks to demonstrate that the philosophies of both Kant and Nietzsche encourage the individual to develop her authenticity. Although Kant appears to be an extremely rational philosopher that does not take into account the emotional sphere of human beings in order to focus exclusively on the notion of duty, I argue that - just as Nietzsche - his thought attempts to direct individuals towards the most positive expression of the self, i.e. towards authenticity.

Although most of Nietzsche’s knowledge of the Kantian philosophy derived from his reading of Schopenhauer, and although he condemns Kant as a “moral fanatic”, “scarecrow”, “philosopher for civil servants”, “cunning Christian”, or “deformed conceptual cripple” (Sokoloff 2006: 503; citing WM I 95; WM I 127; GD “Expeditions” 29; GD “Reason” 6; GD “Germans” 7); I will demonstrate how in both Kant and Nietzsche there is an element of evaluation: in Kant this is expressed through the judging of passions that one feels (and whether they should be acted upon or not); whereas in

Nietzsche this is expressed through the creation of ‘new law-tables’ (TSZ) that ultimately reaffirm the same notions of responsibility and duty.

Moreover, I will attempt to conclude my investigation by analysing their similarities (and differences, whenever possible) with the Ancient Greek philosophical tradition in regards to the forming and expression of the Aristotelean notion of ‘excellence of character’ and authenticity.

CULTURAL BACKGROUND

Before delving into the beliefs both philosophers held, it is essential to provide the cultural and historical background they were situated in.

Kant (1724-1804) is a product of his era, Enlightenment: a period during which science and reason acquired the utmost worth thanks to the publishing of works belonging to authors such as JeanJacques Rousseau, Voltaire, Diderot, D’Alambert, Montesquieu and so on. As Kant states in his essay written in Königsberg (Prussia), What is Enlightenment? (1784), ‘Enlightenment is man’s emergence from immaturity’ and his awakening from ‘laziness and cowardice’ towards a path of freedom that excludes ‘guidance from [others]’.

It is an era that exhorts the individual to practice Horace’s claim ‘Sapere Aude!’ (‘dare to know’) in order to discover freedom of the self, unrestrained by the ‘guidance’ of others who seek to establish their will and ideology on individuals (Kant 1784). However, according to Kant, Enlightenment was possible thanks to the King of Prussia Fredrick II who throughout his rulership refused ‘the arrogant title of tolerance’ and allowed his citizens to exert their freedom in ‘matters of conscience’ and ‘reason’ (Kant 1784). In essence, Fredrick II and his state avoided becoming ‘guardians’ of the ‘their subject’ in the areas concerning ‘arts and the sciences’ (Kant 1784), this is, they avoided intellectual tyranny by nor imposing their own beliefs on others.

Friedrich Nietzsche (1844 - 1900), on the other hand, lived in a very sensitive period for Germany. Firstly, notwithstanding his weak health conditions, he took part in the Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871) and subsequently resigned from his post in academia (1879) in order to focus on the publishing of his major works (O’Hara 2004). In his major work Nietzsche takes great care in condemning the European attitudes and mentality that seem to thwart the subjects’ path towards authenticity and enlightenment. The reader will have the opportunity to understand what I mean by Nietzsche’s concept of ‘authenticity and enlightenment’ in the following sections.

KANT’S IDEA OF MORALITY

(I) The establishment of a scientific and precise morality

Kant’s intellectual freedom deriving from Enlightenment, is mirrored in his philosophy. In 1770, he set out to establish and ‘ground’ the understanding of morality by regarding it as a ‘purely rational science’ (Reich 1939: 341). Kant achieved this objective years later in the Foundation of the Metaphysics of Morals (1785) (Reich 1939: 341).

According to Kant, some actions are morally correct, whereas some are not (notwithstanding the repercussions a deed may have) (Reath 2013).

For Kant there are two types of imperatives which both ‘command’ something: hypothetical and categorical (Cholbi 2016: 15). Hypothetical imperatives are subjective and state what is necessary to do in order to ‘achieve something else that one wills’ (Cholbi 2016: 15; citing G 4: 414). For example, if I wish to go to Vancouver (a), I am required to take a plane from London and attend an eleven hour flight (b). Essentially, hypothetical imperatives as such imply that in order to accomplish (a), one must first carry out (b). If action (b) is not dealt with, action (a) cannot come into realisation. However, although it is necessary for me to take a plane and travel to Canada, it cannot be stated that action (b) is my moral duty: i.e. taking a plane is contingent to my desire, however, I am not obliged to carry it out (i.e. even if I decide not to travel by plane, I will not have violated any laws of morality).

On the other hand, Kant seeks to demonstrate systematically that there are absolute moral truths known as categorical imperatives, able to regulate human behaviour (Razin 2000). These imperatives are ‘objectively necessary’ and do not have an ulterior ‘end’: thus, this type of ‘command’ is useful and ‘good in itself’ because it conforms to reason and can stand as a ‘maxim’ suitable for everyone (Cholbi 2016: 15; citing G 4: 414). When one discusses ‘maxims’ apt for

everyone, one is confronted with laws that are universal.

For instance, Kant’s philosophy introduces ‘maxims’ such as ‘Act only according to that maxim whereby you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law’ (G 421). In this respect, according to Kant, one can grant other individuals consideration and ‘respect’ only when following a personal “maxim” that fulfils duty and that seeks to treat others with equality (Williamson 2015).

My intention in this research is not that of discussing at length the difference between the hypothetical and categorical imperatives. Yet, a major distinction can be observed before delving into the following section of this research. In essence, whilst hypothetical imperatives are not obligations that should be fulfilled in the name of duty; categorical imperatives indicate actions that should be carried out despite the inclinations one may have. Therefore, categorical imperatives are

actions one ‘oughts’ to do because it corresponds to her duty towards herself and society.

(II) The value of deeds

Kant does not believe that the achievement of happiness is a ‘moral duty’ : in fact, if an individual acted exclusively to her own advantage, she would most likely be inclined to ‘privilege [herself] over others’ (Williamson 2015: 7).

Deeds can only be moral if they respond to duty, and they do not acquire additional value when considering the ‘circumstances, emotions and motives’ that lay behind an action (Razin 2000).

Therefore, one should act dutifully regardless of personal preference: the subject’s feelings should not affect the individual’s inclination to act in a morally good or bad manner, and as a consequence, one’s priority should be ‘pure moral intention’ without the fear of immolating her ‘interest’ in order to contribute to the ‘good of the whole’ (Razin 2000). In fact, in What is Enlightenment (1784),

Kant asserts that although individuals possess ‘freedom’ they are not exonerated from carrying out their ‘public’ duty and contributing in the creation of ‘harmony [within] the commonwealth’. In essence, as the government of Fredrick II purported, one can ‘argue as much as [she] want[s] about what [she] wants, but [it is necessary to] obey’ (Kant 1784).

Nonetheless, this does not imply that one is forced to subjugate themselves whenever someone displays attitudes that call for pity: in fact, Kant not only rejects the idea of feeling pity towards others, but also, he asserts that empathising with others’ anguish, misery and torment, does not have any beneficial result considering it serves only to augment the ‘overall world suffering’ (Solanas 2004: 64). Thus, ‘sympathising’ with another person’s discomfort cannot be regarded as a moral

duty (Solanas 2004).

This position also shared by Nietzsche: in fact, as Sokoloff (2006) points out, in the Genealogy of Morals (1887), the philosopher states how many enjoy ‘bleed[ing] on others, [and] display[ing] their wounds’ in order to instil torment and pain in others (:504). However, this defeating and deceptive attitude has repercussions on social interactions: when one does not free oneself of past ‘wounds’, they grow stronger and eventually push the individual towards ‘self-hatred’ and thus, in order not to feel burdened, one will tend to ‘blame’ others as responsible ‘for h[er] suffering’ (Sokoloff 2006: 504). As a consequence, according to Nietzsche, individuals that rely on pity in order to build up strength, “make evildoers out of their friends, wives, children, and whoever else stands closest to them” (Sokoloff 2006: 504; citing GM III 15).

(III) The role of emotions

However, it would be risky to state that Kant disregards and disvalues the individual’s emotional sphere. In fact, he recognises ‘emotions’ as a product and consequence of ‘thoughts’: therefore, the individual must understand the patterns present behind her feelings, and value them in the light of morality (Williamson 2015). In such a manner, one is faced with the necessity of asking herself whether her actions respond to what is morally virtuous (Williamson 2015). As a consequence, Kant’s idea of morality entails a process of self-discovery because it urges the individual to dive

into her deepest self and identify the truest psychological threads behind her own motives (Williamson 2015).

When one reaches an understanding of her emotions, she is able to determine whether it is useful to take action upon them or not (Williamson 2015).

The attitude of analysing one’s own drives and opinions is in itself an act of taking responsibility towards oneself: in fact, by taking responsibility of my ‘passions’ I am able to detect and correct any faulty or immoral aspects of my reasoning, and thus, educate myself on the most virtuous way of acting.

NIETZSCHE’S IDEA OF MORALITY

(I) The illusion of Morality

In his work Will to Power, Nietzsche states that there are ‘no facts’ (i.e. a priori truths), but only ‘interpretations’ (WP 481). Moral judgments are in themselves ‘false and incoherent’ (Lillehammer 2004: 95). Thus, believing in morality is as futile as believing in God since they both rely on ‘realities’ that are ‘no realities’ (TI; ‘The Improvers of Mankind’, 1). Rather, it forbids the individual absolute freedom, and obstructs the path to self-realisation and ‘flourishing’ (Robertson 2011: 592). He states: ‘I deny morality, as I deny alchemy, that is, I deny their premises’ (D 103).

Morality is only an effort to give order to ‘chaos’ in order to bring about ‘stability within a cosmic anarchy’ (Ahern 1995: 13). As a consequence, believing in ‘justice’ and holding a pre-established belief system, is worthless because life itself is not structured in an orderly, precise, and eternal format: quite contrarily, it follows the detrimental motives of ‘injury, assault, exploitation [and] destruction’ (Ahern 1995: 25; citing G 2: 11).

Throughout Nietzsche’s philosophy it becomes evident that there are no fundamental truths, rather, one’s ‘personality’ and ‘character’ are the ‘criteria of value’ (Brobjer 2003: 66). In essence, in the following passages one will observe how it is in man’s very nature to evaluate. There are only interpretations of facts: ‘much that seemed good to one people seemed shame and disgrace to another […], [what] was called evil in another place was in another decked with purple honours’ (TSZ I; ‘Of the thousand and One Goals’).

In fact, Nietzsche celebrates moral subjectivism. In the Last Supper (TSZ IV) Zarathustra encourages the other to celebrate with him by adhering to their own ‘customs’: he claims ‘crush your own grains, drink your water, praise your fare, as long as it makes you gay!’ (Sinhababu 2015: 283; citing TSZ IV; ‘The Last Supper’). It seems clear that according to Nietzsche it is not possible for all men to hold the same values. It is a matter of ‘taste’: what may apply and ‘please’ one, will not necessarily satisfy the other (Sinhababu 2013: 283).

(II) ‘Evaluation is creation’

It has been observed how according to Kant there is a correct way of acting, as opposed to an incorrect one. Nietzsche would disagree with this perspective: morality is subjective, thus there are no pre-established moral codes.

This signifies that I am the creator of my moral views, and not necessarily another individual will agree or conform to my moral outlook: ‘I am a law only for my kind, I am no law for all’ (TSZ IV; ‘Last Supper’). Thus, at the centre of his thought stands the notion of ‘evaluation’ which is the primary force for ‘creation’: the individual gives shape and meaning to the world around her when forming and expressing her own judgments and opinions, i.e. ‘evaluations’ (TSZ I; ‘Of a Thousand

and One Goals’). Moreover, when one ‘evaluates’ she creates ‘value’, and if one did not possess this capability, her ‘existence would be hollow’ (TSZ I; ‘Of a Thousand and One Goals). One’s power stands exactly in the ability of creating meaning(s).

Nietzsche establishes his own subjective morality by killing God. However, it is important to note that in his works Nietzsche does not condemn God in itself; rather, he condemns the effect He has on humanity: i.e. responsible for limiting man’s potential (Brobjer 2003: 71). Therefore, the ‘death of God’ should be regarded as a liberation from anything that keeps one chained, entrapped, restrained. It is a metaphor of the deliverance of what no longer serves the individual, which as a consequence, paves the path towards freedom.

However, creating new values is not a simple task: the terminology employed by Nietzsche in Thus Spoke Zarathustra alludes to the motives of destruction and transformation. For instance, I would like to point the reader’s attention to the word ‘perishing’ in ‘On the Way of the Creator’ (TSZ I). I interpret the act of ‘perishing’ as a state of transformation: it corresponds to the awareness of going towards change, and therefore, towards creation. However, in order to achieve this state of creation, one must be willing to ‘go down and perish’ in order to go ‘beyond’ (TSZ III; ‘Of Old and New Law Tables’: 6). It is essentially the ability to overcome oneself. Therefore, one must be ready to abandon the beliefs she currently holds in order to investigate and meditate upon them before asserting their validity. ‘You must be ready to burn yourself in your own flame: how could you become new, if you had not first become ashes?’ (TSZ I; ‘Of the Way of the Creator’: 90).

It is a process that necessitates great inner strength, resilience and temperance, as it requires being consistent with one’s own will and objectives.

I believe that the sense of creation (as a consequence of evaluation) derives from the transformation itself. Therefore, in order to overcome oneself, and in order to achieve mastery over oneself, one ‘must become judge and avenger and victim of his own law’ (TSZ III, ‘Of Old and New Law Tables, 7).

(IV) The role of emotions

Unlike his predecessors, Nietzsche does not support the existence of a ‘good’ and ‘evil’ morality: what is defined as ‘good’ and ‘bad’ is not to be regarded as in ‘opposition’ (Cameron 1995: 75). For this reason, as Nietzsche states in Will to Power ’an action in itself is perfectly devoid of value: it all depends on who performs it’.

Emotions - or, in Nietzsche’s words ‘passions’ - are the ‘motive force’ that push the individual towards committing to an ideal or acting upon something (WP 387). As a consequence, ‘passions’ cannot be regarded as separate from ‘reason’: rather, they are intertwined and are part of a complex ‘relation between various passions and desires’ (WP 387). In fact, in Beyond Good and Evil (1886) Nietzsche states that ‘moralities [..] are only a sign-language of the emotions’ (Kerruish 2009: 11; citing Nietzsche 1990: 110). It is clear that Nietzsche inserts a psychological dimension in his thought.

Certainly, I am not claiming that Nietzsche’s suggestion is that one should act on whichever emotions flow within us. However, at the same time, trying to restrain feelings or pretending they do not exist is unnatural, and as a consequence, they should be dealt with as they come. Rather, one should ‘direct’ these ‘impulsive’ stimulus that ‘steer us blindly’ towards an objective (Cartwright 1984: 87). ‘Directing’ one’s emotions signifies ‘focusing’ and ‘controlling’ these passions through rational thinking in order to gain mastery over oneself and one’s behaviour (Cartwright 1984: 87). It is only through the use of reason that the subject can give ‘shape’ to these emotions in order to ‘satisfy [her] deepest needs’ (Cartwright 1984: 88).

In essence, emotions and reason work together: whilst passions ‘are the true motors of our actions’, reason helps the individual gain ‘awareness’ and knowledge of herself (Cartwright 1984: 88).

NIETZSCHE AND KANT: A PHILOSOPHY OF AUTHENTICITY

(I) Educating the mind towards ‘excellence of character’

Having discussed the viewpoints that Kant and Nietzsche hold towards morality, as well as the meaning of deeds and emotions in both their philosophies, the aim of this section is that of comparing their thought with the Ancient Greek tradition. In particular, I will draw attention to the philosophy of Aristotle and will seek demonstrate the existing thread between his notion of ‘excellence of character’ and the idea of authenticity in Nietzsche and Kant.

In the previous section, it has been observed how according to Kant ’no emotion can give an agent a moral interest in action, since it determines the will according to the principle of happiness’ (Solanas 2004; citing CPrR 92-3, GMM640). In essence, one’s own emotions (or passions), always strive towards the fulfilment of the subject’s desires in order to attain contentment and satisfaction.

However, Kant accepts emotions as a consequence of an act of duty that has been carried out: thus, in this instance, feelings such as happiness are a mere ‘side effect’ of an action carried out without the presence of ‘self-interest’ (Solanas 2004). Therefore, I am happy because I carried out what I was supposed to do, i.e. my duty (Solanas 2004).

Similarly, in his work Aristotle states that in order to exhibit a morally good character, one should be in sync with herself and her surroundings: one should ‘feel the right emotions at the right time, for the right reason, to the right object, in the right proportion’ (Solanas 2004). It is a philosophy of moderation, of being able to control oneself in each situation and to balance one’s emotions in order to act in the most appropriate manner. However, maintaining balance between duty and emotions should come natural, rather than being forced by the self. In fact, she who is not ‘in tune’ with her own feelings will be required to monitor her behaviour in order to act correctly; whereas, she who acts in ‘harmony’ with her own desires and emotions, will feel contempt when performing the correct action, and unhappy when performing an immoral action (Solanas 2004). The notion of acting ‘harmoniously’ or not, is referred to as ‘hedonic value’ (Solanas 2004).

Although Kant disregards and considers the ‘hedonic value’ redundant for the question of morality, he nonetheless does not deny the ‘personal benefit’ acquired by the individual when acting dutifully and in accordance with her ‘own emotional inclination’ (Solanas 2004).

However, in section IV (‘The role of emotions in Kant’) it has been observed how according to Kant, emotions should be subject to analysis rather than acted upon in an impulsive way: as Williamson (2015) states, they entail an understanding of the self because they encourage one to discern whether an action is dutiful or not, and thus, whether it should be carried out or not. Therefore, I believe that the initial continuous questioning and surveillance of one’s emotions and role in regards to duty, has as a consequence a rebooting of the mind. In essence, I regard it as a training of the mind: one educates oneself and discerns by herself the value of the emotions she has and whether they are healthy feelings that can be acted upon.

Aristotle also discussed the need of educating the mind with his idea of ‘excellence of character’, which I believe is a notion also shared by Nietzsche (I will discuss this in the following section).

According to Brobjer (2003), with Nietzsche one can discuss of ‘ethics of character’: when taking into consideration the etymology of τα εθικα (‘ethics’), one can conclude that it derives from the noun εθος, which signifies ‘character’ (:66).

Before contrasting Nietzsche’s thought with that of the Greek tradition’s thinkers, it is necessary to understand how the Overman may be correlated to the Ancient Greek Gods.

Firstly, I agree with Brobjer that Nietzsche’s objective was that of forging - like a demiurge - an ‘exemplary’ being possessing ‘character’ traits similar to the ones exhibited by the pagan Gods (2003: 67). In essence, he attempts to create an ‘ideal’ (Brobjer 2003: 67).

A fascinating trait that Nietzsche confers to Ancient Greek civilisation is their ability to view any sort of challenge as an opportunity to ‘test’ their vitality and ‘strength’: in fact, their drives and actions do not demonstrate any concern for life-threatening circumstances (Ahern 1995: 34). Their passions are ‘selfdestructive’: by yearning for pain, ‘cruelty and destruction’ they do not hesitate to pursue glory through an ‘intoxicating affirmation of life’ (Ahern 1995). In fact, in the Genealogy of Morals (1887) he praises the glorious and heroic attitude of ‘the magnificent blonde brute’, the boldness and courage exhibited by the Romans, the Scandinavians and German heroes, or Pericles’ ‘ραθυµία’ (i.e. ‘carefree attitude’ [Translation by Samuel 1913]) who exalted and glorified the power of Athens and its inhabitants with the employment of ‘destruction [and] all the ecstasies of victory and cruelty’ (GM I; 11). Moreover, in Human All Too Human (114) Nietzsche writes that the Ancient Greeks did not regard the ‘Homeric Gods’ as an ‘antithesis of their own nature’, this

is, as superior and more powerful beings; and neither did they see themselves as ‘set beneath the gods as servants’ (HH 114). On the other hand, they would look up to the Gods as epitomes of ‘successful’ personalities (HH 114).

Similarly, the character of the Overman, has the ability and the strength to ‘command’ and ‘obey himself’ in order not to be dominated by others (TSZ II; ‘Of Self-Overcoming’).

I believe that Nietzsche’s closeness to the Greeks is more evident. Whilst Kant incorporates the ‘rational’ side of Ancient Greek society, Nietzsche, on the other hand, is the perfect expression of the ‘Dionysian’ side with all its ‘mad, absurd, and spasmodic’ action (GM I; 11).

The Overman takes a leap of of faith towards life and its full expression: she is not afraid of abandoning all certainties and forging - from uncertainty and chaos - her own reality and destiny throughout the employment of her own judgment and evaluation.

However, Nietzsche never states the need to oppose the ‘maxims’ introduced by Kant: in fact, the Overman is to be regarded as a being filled with compassion towards herself and nature, that strives towards the overcoming and bettering of her being in order to reach a more enlightened state of existence. As a consequence, the very nature of the Overman implies that the values she creates are necessarily life-enhancing and throughout the bettering of the self, she can contribute to the welfare of the whole.

Thus, if each individual created a better and more aware version of themselves, they would automatically and naturally reaffirm the ‘maxims’ proposed by Kant.

I interpret this as an indication that man does not need any God or a priori tables of laws that guide and assert the individual’s being. In the XX century, the Existentialists will reaffirm the same message: Jean-Paul Sartre will write in Existentialism is a Humanism (1946) ‘nothing will be changed if God does not exist […] [because] we shall find ourselves with the same norms of honesty, progress and humanism’.

For this reason, the ‘maxims’ that Kant proposes, such as ‘act in such a way that you treat humanity [..] never merely as means to an end, but always [..] as an end’ (1998), or the idea that one should ‘will’ in as much as she does not block another person’s freedom, recall the motives of dignity and respect towards the other, and are natural laws that are to be respected in order to maintain an organised society in which one can live peacefully. In fact, if individuals did not respect ‘maxims’ (either imposed by Kant or by God), one would live in an immoral society that threatens and thwarts equality.

CONCLUSION

I believe Nietzsche’s purpose was that of creating a work that would resist the test of time: an everlasting philosophy that would place the individual at the centre of the inquiry and hold her entirely responsible for her drives and actions. One of the primary morals we can gain from Nietzsche, consists in the fact that ‘evaluation is creation’: this is one’s true purpose (TSZ I; ‘Of a Thousand and One Goals). In fact, stating that there are absolute or apodeictic truths requires denying the subject’s power of creating meaning by herself. After all, how can a priori truths be established in a universe ruled by confusion? As Ahern (1995: 13) explains: ‘[t]he universe is the child of chaos; nothing is stable; nothing remains. Assertions o “reality” and “truth” are the attempts of one form of power to realise stability within a cosmic anarchy’.

Whilst Nietzsche attempts to develop a philosophy of empowerment and self-development, that aims at strengthening one’s character throughout an extremely poetic and metaphorical language (as it can be seen in TSZ); Kant, on the other hand, promotes an ethics of reason that seeks to demonstrate that by valuing one’s emotions and respecting the a priori ‘maxims’, a common well-being and happiness can be granted.

Essentially, by observing and correcting one’s own inclination in order to act dutifully (Kant); and by creating values that are life-enhancing, as well as ‘directing’ one’s passions towards an objective (Cartwright 1984: 87) one can achieve authenticity, and therefore, express ‘excellence’ of character.

I believe both the views held by Kant and Nietzsche - although seemingly opposed in terms of what they want to confer - go hand in hand, an ultimately cherish and promote the ‘flourishing’ (TSZ) of humankind.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ahern, D. (1995). Nietzsche as cultural physician. USA: The Pennsylvania State University.

Brobjer, T.H. (2003). Nietzsche’s Affirmative Morality: An Ethics of Virtue. The Journal of Nietzsche Studies. 26 (1). Pp. 64-78.

Cameron, F. (1995). Nietzsche’s Ethics of Character: A Study of Nietzsche’s Ethics and its Place in the History of Moral Thinking by Thomas H. Brobjer. Journal of Nietzsche Studies. 17. Pp. 73-77.

Cartwright, D.E. (1984). Kant, Schopenhauer and Nietzsche on the Morality of Pity. Journal of the History of Ideas. 45 (1). Pp. 83-98.

Cholbi, M. (2016). Understanding Kant’s Ethics. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

Kant, I. (1784). An Answer to the Question: “What is Enlightenment”?. [online] Available from: < http://library.standrews-de.org/lists/CourseGuides/religion/rs-vi/oppressed/kant_what_is_enlightenment.pdf> [Accessed 13 December 2017].

Kant, I. (1998 ed.) Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals (Translated and Edited by Gregor, M., with an Introduction by Korsgaard, C.M.). United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

Gardner, S. (1999). Kant and the Critique of Pure Reason. London and New York: Rutledge.

Kant, I. (1998). Kant’s Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals (ed. Guyer, P.).USA: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

Kerruish, E. (2009). Interpreting feeling: Nietzsche on the Emotions and the Self. Minerva. 13. Pp. 1-17.

Lillehammer, H. (2004). Moral Error Theory. Proceedings of the Aristotelean Society. 104. Pp. 95-111.

Nietzsche, F. (1886). Beyond Good and Evil, ed. Hortsmann, R.P. and Norman, J. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

Nietzsche, F. (1982 ed.) Daybreak: thoughts on the prejudices of morality (translated by Hollingdale, R.J.). C.U.P.

Nietzsche, F. (1911). Ecce Homo. [online] Available from: < http://www.gutenberg.org/files/52190/52190-h/ 52190-h.htm> [Accessed January 2 2018].

Nietzsche, F. (1986 ed.) Human, All Too Human: a book for free spirits (translated by Hollingdale, R.J.). Cambridge, New York, Port Chester Melbourne, Sydney: Cambridge University Press.

Nietzsche, F. (2003 ed.) The Genealogy of Morals. Mineola, New York: Dover Publications Inc.

Nietzsche, F. (1923 ed.). The Antichrists (Translated from the German with an Introduction by Mencken, H.L.). [online] Available from: < http://www.gutenberg.org/files/19322/19322-h/19322-h.htm> [Accessed 3 January 2018].

Nietzsche, F. (1961 ed.) Thus Spoke Zarathustra (Translated with an Introduction by Hollingdale, R.J.). London: Penguin Books.

Nietzsche, F. (2005). The Anti-Christ, Ecce Homo, Twilight of the Idols, and Other Writings (edited by Ridle, A. and Norman, J.). United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

Nietzsche, F. (1968 ed). The Will to Power (translated by Hollingdale, R.J.; edited by Kaufmann, W.). New York: Vintage Books.

O’Hara, S. (2004). Nietzsche within your grasp. New Jersey: Wiley Publishing Inc.

Razin, A. (2000). Nietzsche and Values. Philosophy Now. [online] Available from https://philosophynow.org/issues/29/Nietzsche_and_Values [Accessed 22 December 2017].

Reath, A. (2013). Kant’s Moral Philosophy. Oxford Handbook of the History of Ethics. [online] Available from: <http://www.oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199545971.001.0001/ oxfordhb-9780199545971-e-21?print=pdf> [Accessed 27 December 2017].

Reich, K. (1939). Kant and the Greek Ethics (I). Mind. 48 (191). Pp. 338-354.

Sartre, J. P. (1946). Existentialism & Humanism. Great Britain: Methuen.

Sinhababu, N. (2015). Zarathustra’s metaethics. Canadian Journal of Philosophy. 27 (1). Pp. 278-299.

Sokoloff, W.W. (2006). Nietzsche’s Radicalization of Kant. Polity. 38 (4). Pp. 501-518.

Solanas, M.B. (2004). Kantian Ethics and Aristotelean Emotions: A Constructive Interpretation. Teorema: Rivista Internacional de Filosofia. 233 (1/3). Pp. 57-70.

Williamson, D. (2015). Kant’s Theory of Emotion: Emotional Universalism. USA: Pagrave Macmillan.

To listen to the audio version of this article click on the play image.

Brought to you by @tts. If you find it useful please consider upvoting this reply.

You got a 3.73% upvote from @postpromoter courtesy of @francescap1995!

Want to promote your posts too? Check out the Steem Bot Tracker website for more info. If you would like to support the development of @postpromoter and the bot tracker please vote for @yabapmatt for witness!

@francescap1995 you were flagged by a worthless gang of trolls, so, I gave you an upvote to counteract it! Enjoy!!

Congratulations @francescap1995! You received a personal award!

You can view your badges on your Steem Board and compare to others on the Steem Ranking

Do not miss the last post from @steemitboard:

Vote for @Steemitboard as a witness to get one more award and increased upvotes!

time resistant work is da best