The Impact of Parental Death Upon Children

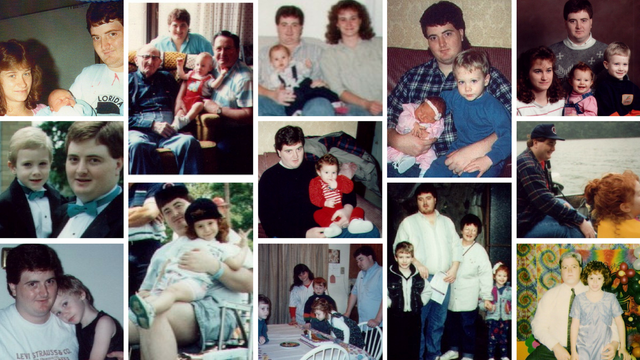

I thought I should give you some background on this paper before you read it. I wrote this for my college psychology class final paper in 2001. We had to pick the topic early in the year, and since we knew the kid's father, Tim, had cancer I figured it would be a good topic to learn about, just in case.

I never thought about having to read it in front of the class during a difficult time. I had to read it in front of them just about a week before we lost Tim to the cancer. It was challenging, but I made it though better than I thought I would. I found this information is hard to come by and I would like to share it with anyone who may need it.

Keep in mind, that I am not a professional. I attained this information through research in 2001 and its always a good idea to seek professional advice when you need it.

The Impact of Parental Death Upon Children

The impact of parental death upon children is harsh, but can be overcome, for most, if the child has adequate support from family members and friends. The death of a parent can affect children in many different ways. Those ways are often reflected by the child's age at the time of the parent's death. Providing realistic memories of the deceased parent can be helpful to the child's grieving periods. Seeking professional help for children can help with their recovery. The recovery process may take many years and may especially affect the child at the time of a celebration or crisis.

If the parent is not deceased, but is dying of an illness such as cancer the child will usually be aware of the illness for quiet some time, and this will provide time to start talking to the child about the illness and death. It is important to let the child know that not all illness ends in death. Prepare the child by being honest, and let the child visit the dying parent as often as they want to. It is important not to keep the child from the dying parent at the time of death. Children are often more accepting of this than adults are and it can help the child in facing the reality of the parent dying. It may also provide the child a chance to say goodbye. If the child is not there at the time of the parent's death, tell them of it as soon as possible, preferably at home. Letting the child see the body will help establish that the deceased parent will not be returning.

A child as young as two and a half understands the idea of saying goodbye, so allowing a child of any age to attend the funeral is ideal, unless the child voices that they do not wish to attend it. Answer their questions honestly and talk about any concerns they have. Many children are concerned about the casket, burial, or cremation of a deceased parent. These things need to be explained at a level equal to the child's age and ability to understand. It is helpful to some children if they can write a letter, draw a picture, or place a memento or a flower in the casket. It is quite normal for a child to re-enact the funeral or sickness in play after the loss of a parent.

A child's grief is similar to adults, but they lack the ability to understand and cope as an adult does. They feel less in control of their world than an adult does, and they grieve more sporadically than adults. Children are more able to focus on more pleasant things and putting grief aside than adults are. They do not have the responsibilities that adults have to deal with, such as funeral arrangements.

The grieving processes of a child are denial, anger, guilt/regret, depression, and fear. Denial, it is common for the child to wait for the deceased parent to return; this is caused by the shock of the event. It is normal for a child to step out of the real world and into an imaginary one that they can handle. However, it is important to eventually bring the children back to reality. This can be done by softly providing them with the facts. Anger, grief comes out as anger because the emotions the child is feeling are powerful and confusing. A child does not know how to deal with these feelings, so it often comes out in disruptive behavior. The surviving parent needs to teach the child to express this emotion in a more acceptable manner. Guilt/Regret, these two feelings can be overwhelming to a child and they may keep them a secret that is shared with no one. If they are having these feelings they may become sullen and depressed or uncommonly good, and they may even start blaming someone else for the death. Talking to the child is the best way to deal with these emotions. Depression, this feeling almost always follows the loss of a parent. The signs of it are, unable to concentrate, withdrawing to their room and not doing anything with friends, not being able to sleep, un-normal eating habits, not caring about their appearance, sadness, and no interest in others. It helps to talk to the child and find activities they are interested in doing. Fear, the death of a parent makes the safe world of a child suddenly become insecure. They do not understand the things happening around them after the death. They may cling to the surviving parent for fear that they will leave them too. Talking is the most important way to deal with these feelings. Making special time for the child is helpful to their feelings of security. Help the child to identify their fears and to learn how to cope with them. Nightmares are often a manifest of fear. Have the child draw a picture of their dream or write a story of their fear; then have them change the ending or the picture to something good. These stages can be difficult to get through, but love and understanding can help a great deal.

It is very important for the bereaved child to be able to discuss their feelings about the deceased parent. The child should be able to discuss these feelings with a variety of people, including the surviving parent, family, family friends, or even a professional. Support from these people in the child's life proves essential. If the child is not expressing these feelings, ask what they think. Be honest with the child to avoid them becoming confused with half-truths or fears. Correcting or confirming facts, and reassuring fears are important. Being able to discuss how it was with the deceased parent and how it is without them is helpful to the child. Be accepting of their grief, this can be spread over many years. Most children will need to hear and discuss things over and over again. Listen carefully to the child, as grief is not always obvious. Children need their feelings of loss confirmed often, so it is important to listen to what they have to say. Children may worry about who will take care of them if something happens to the remaining parent. The parent should assure them that it is unlikely anything will happen to them, and that if it does someone they know and love will take care of them. Most importantly the child will need more reassurance, love, attention, and a secure environment. If the child has many behavioral problems or they persist contact a family doctor or the school principal; they can help in finding a therapists specializing in bereavement and grief.

A child's reaction to the death depends on their age. Up to two years old, the child will not understand death, but will notice the absence of a parent. They may cry more, change their eating habits, or there could be bowl and bladder upsets. Two to five years old, the child may look for the deceased parent, because their understanding of death is still limited. Behavioral patterns may change in the child, if a parent is concerned about this, they can seek a doctors advice. Children of this age may have stomachaches, rashes, headaches, tantrums, and may even convert back into baby habits, such as sucking their thumb. They may also become afraid of the dark or suffer from anger, sadness and anxiety. Six to pre-teens may face the extra stress of friends and classmates asking them questions. Talk to the child's teachers and prepare the child for these questions. Ask the teacher to prepare the class before the child returns to school. Let the child choose what they do and do not wish to tell about the parents death and illness. Children of these ages may get especially upset around the times of holidays. They may also try to assume the role of the missing parent and this should not be encouraged. A child of this age may also rebel against authority; these reactions are a cry for help and it is important to deal with the child's grief. Some forms of acting out or being out of character in school, and school work suffering is normal when a parent dies, but should pass. It is important to stay in contact with the teachers, and the counselor at the school. It is helpful for everyone who knows and is around the child often to keep each other informed. This can help in knowing how your child is grieving. If these problems continue seek professional help.

Teenagers are in a different category from younger children. They understand death and it is frightening to them. Bereavement is an added layer to the already complex life they have. Teenagers are dealing with their body and mind changing from childhood to adulthood. They will often confide or find help outside of the home, and the remaining parent should not let this be a reflection on themselves. Their friends may not know what to say and they may avoid them because of it. This may leave them feeling isolated. Teenagers may suffer depression, change friends, use drugs, run away, become sexually promiscuous, or may even become suicidal. If any of these factors are a concern seek professional help immediately. Ask teachers and youth leaders to help in looking for any signs of abnormal behavioral changes. Teenager's emotions can be intense even if they choose to hide them. They may try to protect the surviving parent by hiding how they really feel. The surviving parent needs to give them 'permission' to express what they feel and think. Knowing that it is okay to talk about is important and the remaining parent can help by leading them in the direction of talking about it. It is important to let them know it is okay to cry and be upset. Keeping the teenager busy in healthy releases of emotions such as sports or activities can be essential to their healing process. It may take years for a teenager to work through their grief. They may be confused and need help in knowing what to do to make decisions that focus on their own needs.

In general for all children and teenagers, grief has many patterns and could continue for years. Patience, understanding, love, attention, talking, support, and possible professional help, are some of the best ways to help the child deal with their grief. They have to learn to reorganize their life and return to a normal routine of activities and relationships. Children may seem angry and need someone to blame for the death of their parent; stay away from telling them that God has 'taken' them. Instead simply tell them the truth. It may be hard, but you need to use real words that apply to what happened, such as cancer, car accident, and murdered. This seems harsh to tell a child, but truth is what the child needs to hear and know to help in the healing process Sometimes, using humor can lighten the pain when the child is thinking of the deceased.

Making a connection to the deceased is vital. Children of all ages need to 'locate' the deceased. Most families can do this through their religious beliefs. It is helpful for the child to keep something that belonged to the deceased parent. Talking about and remembering events the deceased participated is important. Acknowledge the deceased parents birthday, and other significant dates. The child maintaining a link to the deceased parent is important for them, and to their healing process.

In conclusion, the impact of parental death upon children of any age is hard. The stages of grief are not easily overcome and they require the support of the surviving parent, family members, and friends. The child needs to get back to and maintain a secure routine, in a loving environment. If they are having too many problems adjusting it is okay to seek professional help with their recovery.

Bibliography

Dan Schaefer and Christine Lyons. How Do We Tell The Children? (1986) Newmarket Press.

Helen Fitzgerald. The Grieving Child. (1992) Simon & Schuster

Mary Ann Emswiler, M.A., M.P.S. and James P. Emswiler, M.A., M.ED. Guiding Your Child Through Grief. (2000) Bantam Books

This is an excellent article @debralee. You can also use the psychology tag.

Thank you, I will add that tag.

Hi, debralee! I just resteemed your post!

I can also re-steem and upvote some of your other posts

Curious? Check out @resteembot's' introduction post

PS: If your reputation is lower than 30 re-blogging with @resteembot only costs 0.001 SBD

@originalworks

The @OriginalWorks bot has determined this post by @debralee to be original material and upvoted it!

To call @OriginalWorks, simply reply to any post with @originalworks or !originalworks in your message!

There is a sponsored @OriginalWorks contest currently running with a 125 SBD prize pool!

For more information, Click Here!

Special thanks to @reggaemuffin for being a supporter! Vote him as a witness to help make Steemit a better place!

Thanks!