Caudillismo in Latin America

The phenomenon of Latin American Caudillismo in the 19th century

... and that persists in the 21st century

by Susana Rebon López

The process of Independence is one of the essential factors that led to the appearance of the caudillo as a figure of power. The vacuum of authority in vast geographical regions, such as the llanos of Venezuela and the pampas of Argentina, led to the increase of the banditry which took shape in impunity. The members of these bands, being skilled with weapons, especially rude and cruel, and connoisseurs of the country, in the crucial moments of the struggles of independence, were captured to their ranks by both sides in conflict. In some cases they were peons of the large farm or haciendas who, because of the disorder, had lost their masters, others were simply adventurers or fugitive slaves, there were also defectors of war. In any case, they were people who were living in a extremely hostile environment, to which only survived in a group, and who, with their peculiar form of organization, offered a solution of order to the chaos of the moment.

A group of these characteristics always requires a leader, and in this case, leadership was characterized by strength, courage, audacity, a strong will and fear that they were capable of instilling in their followers. They were charismatic leaders by nature, and being illiterate people grown in very narrow contact with the nature, their decisions were made more intuitively than rational. They were telluric and visceral personalities, accommodated only to his will, or to the will of a stronger one. They were beings handed to passions, fond of women, the game of roosters and the bets, born seducers. The cities and their way of life adapted to the citizen norms were unknown to them. They lived and died practically in the same place where they were born.

In Venezuela came out of this way as caudillo José Antonio Páez, and in Argentina we have Facundo Quiroga. In Mexico emerges Santa Anna, who in this case comes from the regular army, and is the son of a lawyer and colonial official. So we can pose as a possible hypothesis, that more than a matter of upbringing, or geographical determinism, it was a matter of willing and indomitable personality, conditioned and valued by the circumstances of the war, and that in conditions of peace, most of them, it would only be in the best of cases, social misfits reluctant to any form of authority, or in a extreme case, very effective criminals.

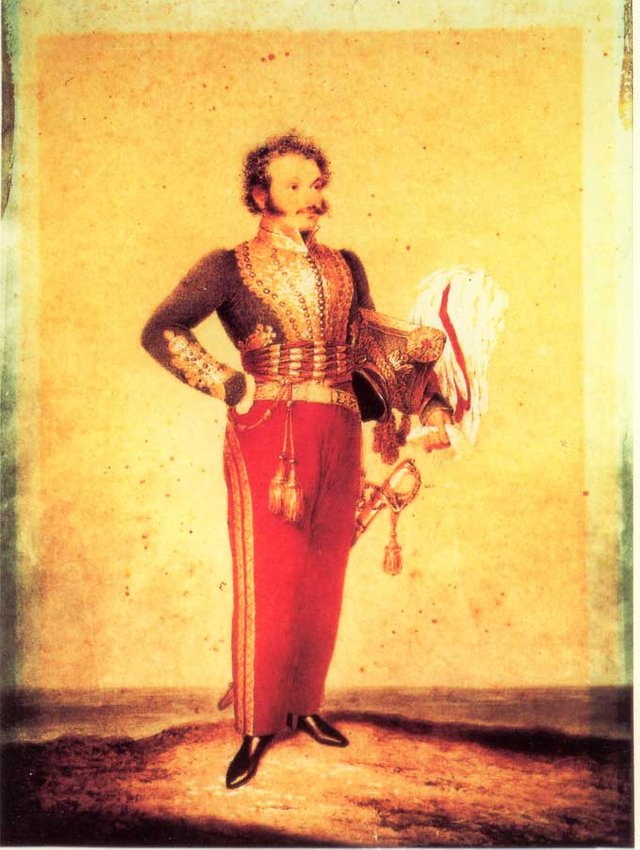

Antonio López de Santa Anna [a]

In his Autobiografía, José Antonio Páez tells us:

"Such was the life of those men. (...) The ringing of the bell that reminded them of religious duties never came to their ears, and they lived and died as men who had no other destiny than to fight with the elements and beasts, and their ambition was limited to one day to be foreman in the same point where he had previously served in peon class." [1]

They were men especially gifted physically to be able to resist and impose themselves in such a hostile environment. They copied somehow the ways of the beasts with which they shared the environment. The nicknames would refer to these. We have Páez called him the Tigre de Payara, and Facundo the Tigre de Los Llanos, titles always won in actions of extreme violence, whether against the beasts or against enemies of any kind, personal or political.

Facundo Quiroga [b]

Facundo is described to us by Sarmiento:

"His black eyes, full of fire and shaded by crowded eyebrows, caused an involuntary sensation of terror in those upon whom, some time, they were fixed; because Facundo never looked at the front, and by habit, for art, for the desire of becoming fearsome, had his head usually bowed and looked through his eyebrows (...) " [2]

However, contrary to what one might think, they valued their way of life above what they assumed to be the way of life of the citizens, which they perceived as weak, since many of these leaders only came to know them in the years , when gained Independence served as support to hacendados and estancieros, who entering into politics wanted to assert their position against the city, or as in the case of Páez and Facundo, when already generals directly assume positions of government, national and provincial.

José Antonio Páez [c]

The perception of Páez is eloquent:

"The struggle of man with wild beasts -which are nothing more than horses and wild bulls- is a constant struggle in which life escapes as of miracle, a struggle that tests the bodily forces, and which needs an unlimited moral resistance, much stoicism (...); That struggle, I say, had to be and was a terrible ordeal. (...) This was the gym where I acquired the athletic sturdiness that was very useful to me many times later, and that even today many men envy me in the vigor and strength of their years. My body, by force of blows, became of iron, and my soul acquired, with the adversities in the first years, that temper that the most careful education could hardly have been able to give it." [3]

Those who looked like this, could hardly do anything but impose their forms on a community, once they have the power to do so. The confrontation between the values of the countryside and the city in the formation of the new nations is inevitable. Once the power granted by the victory in the War of Independence is in the hands of the caudillos, it will hardly yield to the politicians of the cities, or it can be subtracted to them by the civil power, although the reason bases the actions of these last. And it could not be otherwise. Their actions are dictated by irrationality based on terror and their own ignorance and the majority of the population.

"Facundo is a type of primitive barbarism: he did not know the subjection of any kind, his anger was that of the beasts (...) In the inability to handle the springs of civil government, he put terror as a record to replace patriotism and abnegation; ignorant, surrounded by mysteries and becoming impenetrable, using a natural sagacity, an uncommon ability to observe and the credulity of the plebe, pretended a prescience of events that gave him prestige and reputation among vulgar people." [4]

They embrace any political tendency, they can either support federalism or centralism as forms of government to be implemented, the one that favors them more personally, and they change their position when it is unfavorable to them; in any case there is no other support in their decisions. However, in almost all cases, if the city imposed the centralist regime, the regions rebelled because they did not feel represented in the decisions taken from the central power and therefore demanded that the government be the federal one. In the case that the city advocated a federal government, the regional caudillos wanted to impose their position on each other, the federal government being unable to reconcile the positions found, so that the strongest caudillo ventured into the city to impose its policy, which generally preclaimed itself to be federalist in use, the action was typical of a central government.

In short, the regime that managed to impose itself in the first years of life of the independent nations was the central conservative republican government, which after new fights would give way to federal governments of liberal type.

Once they assume power, by force and terror, the caudillos take possession of the communal goods, monopolizing in their hands the main sources of economic wealth of the region that is under their government until decimate them in the majority of cases, which gave them the necessary goods to undertake the campaigns to gain power at the national level. Then, at the slightest excuse of warlike action they might undertake, the work of government delegates them to the most affectionate subordinate. They were men of war.

The network of relations that supported the power of the caudillos was established based on the friendship and compadrazgo between the leaders. They must know personally the individual in which they delegate. And their adherence had to be unconditional, at the risk of losing personal wealth and life in case they disagree.

Local and provincial caudillos are the basis of the power of the national caudillo within a pyramid organization. With subordinates, the relationship is from employer to client. In Venezuela this relation derives from the one that has from the colony the hacendado and the peon, in Argentina between the estanciero and the gaucho. The patron protects and rewards the client according to their work and at the cost of a total adhesion. The caudillo rewards with lands or official positions to be preyed upon. It depends on the moment.

After the Wars of Independence the institutions of civic government have disappeared or they do not have the force to impose the norm, for which reason the caudillo is called. That is in essence its function. In the face of chaos the autocratic order that would help to form the new national states is less evil.

"In taking power the caudillo usually followed a dual process: first he exercised informal authority and then actually took office as supreme executive, whether president o governor. But office did not replace a caudillo´s power or become a substitute for his authority: it simply confirmed his position and reinforced his original capacity to take decisions and impose order, a capacity which he had won by his personal qualifications, his response to war, and his reaction to politics." [5]

The civil power would come later in Latin America, at the cost of a vital sacrifice and patience of the people, however their permanence has not been stable. There are still states in Latin America that, although they call themselves democratic, are led by de facto national militarism.

REFERENCES

[1] José Antonio Páez, "Autobiografía", Caracas, PDVSA, 1989. p.38.

«Tal era la vida de aquellos hombres. (…) Jamás llegaba a sus oídos el tañido de la campana que recuerda los deberes religiosos, y vivían y morían como hombres a quienes no cupo otro destino que luchar con los elementos y las fieras, limitándose su ambición a llegar un día a ser capataz en el mismo punto donde había servido antes en clase de peón».

[2] Domingo F. Sarmiento, Facundo. Capítulo 5, Vida de Juan Facundo Quiroga.

http://www.cervantesvirtual.com

«Sus ojos negros, llenos de fuego y sombreados por pobladas cejas, causaban una sensación involuntaria de terror en aquellos sobre quienes, alguna vez, llegaban a fijarse; porque Facundo no miraba nunca de frente, y por hábito, por arte, por deseo de hacerse temible, tenía de ordinario la cabeza inclinada y miraba por entre las cejas (...)»

[3]José Antonio Páez, Autobiografía, Caracas, PDVSA, 1989. p.38.

«La lucha del hombre con las fieras –que no son otra cosa los caballos y los toros salvajes- lucha incesante en que la vida escapa como de milagro, lucha que pone a prueba las fuerzas corporales, y que necesita una resistencia moral ilimitada, mucho estoicismo. (…); esa lucha, digo, debía ser y era durísima prueba. (…)Este fue el gimnasio donde adquirí la robustez atlética que tantas veces me fue utilísima después, y que aún hoy me envidian muchos hombres en el vigor y fuerza de sus años. Mi cuerpo, a fuerza de golpes, se volvió de hierro, y mi alma adquirió, con las adversidades en los primeros años, ese temple que la educación más esmerada difícilmente habría podido darle».

[4] Domingo F. Sarmiento, Facundo. Capítulo 5, Vida de Juan Facundo Quiroga.

http://www.cervantesvirtual.com

«Facundo es un tipo de la barbarie primitiva: no conoció la sujeción de ningún género; su cólera era la de las fieras. (…) En la incapacidad de manejar los resortes del gobierno civil, ponía el terror como expediente para suplir el patriotismo y la abnegación; ignorante, rodeábase de misterios y haciéndose impenetrable, valiéndose de una sagacidad natural, una capacidad de observación nada común y de la credulidad del vulgo, fingía una presciencia de los acontecimientos que le daba prestigio y reputación entre las gentes vulgares».

[5] John Lynch, Caudillos in Spanish America. (1800-1850), Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1992, p. 411.

BIBLIOGRPHIC SOURCES

HALPERING DONGHI, Tulio,

Historia Contemporánea de América Latina,

Madrid, Alianza Editorial, 1972.

LYNCH, John,

Caudillos in Spanish America. 1800-1850,

Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1992.

PÁEZ, José Antonio,

Autobiografía,

Caracas, PDVSA, 1989.

DIGITAL SOURCES

http://www.ancmyp.org.ar/user/files/Presidencialismo1.pdf

Dardo Pérez Guilhou

Presidencialismo, caudillismo y populismo.

http://www.cervantesvirtual.com

Domingo F. Sarmiento, Facundo. Capítulo 5, Vida de Juan Facundo Quiroga. Capítulo 6, La Rioja. Capítulo 7, Ensayos.

http://www.pbs.org

Antonio López de Santa Anna.

IMAGES

a.- Antonio López de Santa Anna | https://goo.gl/dRqRhx

b.- Facundo Quiroga | https://goo.gl/5pHTeG

c.- José Antonio Páez | https://goo.gl/GZ4GuE

This post has been upvoted for free by @minibot with 5%!

Get better upvotes by bidding on me.

More profits? 100% Payout! Delegate some SteemPower to @minibot: 1 SP, 5 SP, 10 SP, custom amount

You like to bet and win 20x your bid? Have a look at @gtw and this description!

Congratulations @srebon! You received a personal award!

You can view your badges on your Steem Board and compare to others on the Steem Ranking

Do not miss the last post from @steemitboard:

Vote for @Steemitboard as a witness to get one more award and increased upvotes!

!cheetah ban

Failed ID Verification