The Decline of the Aristocracy (by 1900) – Politically and Personally

obsolescent breed of heroes and not weep?

Unicorns, almost,

for they are fading into two legends

in which their stupidity and chivalry

are celebrated. Each, fool and hero, will be an immortal.(1)

image source

The Aristocrat – no other class of people has fascinated so many, been written about, made fun of, envied, or otherwise studied. But what happened to them. Where they were once the toast of the town, today they are fading into the annals of history to stand side by side with others lost to bygone eras. Although there are certainly still aristocrats around today, they have neither the numbers, the wealth, nor the power of previous nobility and their lives are very different to that of an ancestor in their heyday. Looking at what happened, there are two parts to the question of whether the aristocracy had declined by 1900. The first involves the aristocracy as a political entity, and the second is that of the aristocratic class of people. The second survived longer than the first, but not by much, in its original form. Many changes were to be seen during the Victorian era, and the aristocracy figured heavily in more than one way. From major reforms, to wealth, to political upheaval, to industrial development and international trade, the aristocracy were linked to each change, most often to their detriment. In Continental Europe things had developed differently with the aristocratic societies, but I think we can use the term ‘the decline of the aristocracy’ by 1900 with some degree of confidence, as being correct in both the political and personal sense, in England at least, and indeed greater Britain, and the end of an era.

image source

The majority of the class of aristocracy(2) came from hereditary titles given to an ancestor and which meant they automatically had a seat in parliament, so many of them were the leaders, the movers and shakers of the country, held the power but also the responsibility. In the end, their downfall was linked to the very land-locked power which had carried them along as the patricians of England’s people. Being a member of the nobility did not mean having immunity from the effects of taxes, reforms, bad feeling and attacks from other classes, bankruptcy, or economic depression. One of the biggest financial cripplers of the aristocracy was the government’s introduction of a death duty in 1894. Considering the size and financial worth of some of the larger aristocratic estates, the death of the head of the household or titled gentleman – or woman - could mean the family would be left with a very hefty tax, and, as many were asset-rich but cash-poor, scrambling to find the funds to pay it; and if the next to inherit also died fairly quickly, before the coffers were restored, then the financial blow was often crippling and the family’s prior level of wealth unrecoverable. Along with the agricultural depression in the second half of the nineteenth century – brought on by an increasing market glut of land-based produce from developing countries - this could mean that large chunks of land had to be sold off. Unfortunately for them, land values dropped, and so had land rents. From the 1880s land was no longer the great commodity or asset it once was, and in some cases became a millstone around the aristocrat’s neck, especially as mortgage interest rates began to eat large chunks out of any profits and banks were becoming very cautious about lending or refinancing on landed security. In parliament there were moves to unlock the land from the gentry’s grasp, and open it up for purchase by those in the lower classes. This often meant the loss of thousands of acres from a large estate in the country, and the tenants ‘who were well aware of the massive fall in land values’(3) offered to purchase, it was often at prices well below what the land could have been worth. The aristocrats who continued to do well financially had been wise enough to invest in property in the cities, and were landlords of people, shops, or factories. In some cases an aristocrat was even known to sell up completely and move overseas, perhaps to one of the new territories such as the United States of America to make his fortune, turning his back on both whatever entitlement his nobility had still afforded him, and whatever was going on back home, such as a change in focus of government at both local and national levels.

Trentham Estate

image source

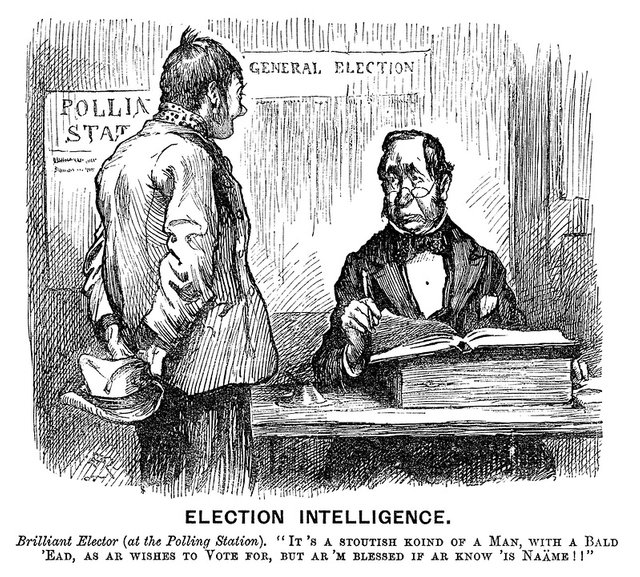

The great move towards democracy in England was gathering momentum during the nineteenth century and the aristocrats found their place in society getting tenuous after the 1870s. “Democracy as it began to emerge in late nineteenth-century England could not coexist with aristocracy, and the evident failure of the traditional establishment…undermined its position in the state.”(4) Politically, the aristocracy was well and truly ‘dying’ by the 1880s. The introduction of reforms involved changing voting boundaries and parliamentary seats, and meant that the more industrialised populations rather than the agricultural populations, where the aristocracy had their traditional seats, were encompassed, and the opening up of voting to more people meant the aristocracy were losing their footing in the top rungs of power. The voters had always been inclined to favour putting those in power who would keep them in employment, so with the move from an agricultural-based country to an industrialised one, their loyalties moved also, to upwardly-rising plutocrats with their new, and often very considerable, wealth. “If voting continued to be an act of personal service to a magnate rather than an expression of individual opinion, the magnate might well be changing from a landowner to a businessman.”(5)

image source

Although “…the size of the English peerage remained roughly constant, at something under 200, from the Revolution until the advent of the Younger Pitt.”(6) and did not markedly drop until the advent of World War I, where many noble families lost men who were either titled or in line to inherit a title, their place in the political and social hierarchies of England had declined remarkably by the year 1900. Even though the numbers of titled men had in fact increased, due to the bestowing of new honours on men from the lower ranks - ones who had money and ambition - in an attempt by the government to create the numbers of peers necessary to see to the passage of the Reform Act(7) in 1832. This Act was to usher in a major change to the political landscape of England, as it allowed those who did not own landed property to have a voice in the running of the country and lessen the power of the Lords in parliament. Then in 1867, with the second Reform Act(8), the number of eligible voters swelled again. Many of the Lords objected on the grounds that this was about the quantity rather than the quality of available voters. The third and final Reform Act(9) in 1884 which opened voting to most males, and the Redistribution of Seats Act(10) in 1885 which created great changes in parliamentary seat distribution, completed the great upheaval of the political landscape and the decline of the aristocracy as a form of governing body, so the aristocratic government as a ruling system had all but disappeared in the Britain by 1900. While there were those of the nobility who still had, or gained, high-privilege positions in parliament, it was no longer a given fact that one of the gentry would gain a seat at the elections, and in fact many did not, with some even retiring from the political arena altogether. In part this was attributable to the fact that some of the gentry could no longer afford to support their political positions because of the downfall of their land-based incomes. Traditionally the nobility in their part-time parliamentary roles were not compensated financially, it was understood that their landed incomes would support them, and it was a duty to use their political seat in the House of Lords or whichever other parliamentary position they had. In local government there were similar changes happening. ‘By the 1880s, some heavily industrialised shires were effectively governed by JPs of non-landed background…’(11) usurping the role of the landed gentry who had previously meted out the law in their local shires and boroughs. More and more of the local county council seats around Britain were being filled by those of the middle classes ‘and as local government became more bureaucratic and more professionalised, the old style of amateur, traditional, patrician administration seemed increasingly inappropriate and anachronistic.’(12) In national politics a new party was set up to develop the rights of the working class, and there was greater representation by these labouring forces, further alienating the old aristocratic ways. Even in the House of Commons those who had been assured of gaining a seat due to the longstanding traditional nepotism, could no longer be sure of having a place in parliament.

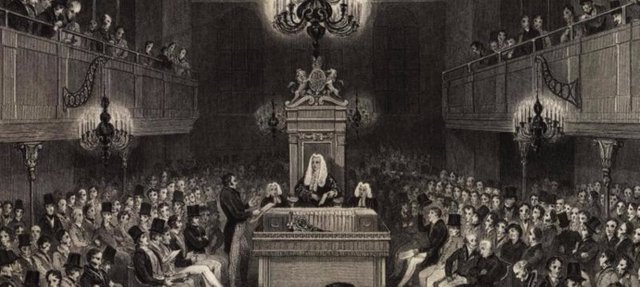

image source

They did not just roll over and admit defeat without a fight though, as the House of Lords held the right to veto legislation as it came through for approval before it was passed into law. This was eventually taken away from them but not without a struggle. Their dissention caused the public to protest against the actions they were taking – or blocking, as the case may be – and during 1884 ‘at least 1,500 public meetings were held to protest against the peers’ action…there were demands that three hundred peers should be created, to ensure the passage of the [Franchise] bill’(13) Demand came from all quarters of society to end the power of the House of Lords, and therefore aristocratic rulership. Luckily, for them, men such as Lord Salisbury sought to restyle the duties of the upper house, and so the system managed to survive, but not quite as before.

Lord Salisbury in Parliament - the House of Lords

image source

By the time the year 1900 rolled around, the past decade had seen major upheavals within both areas of aristocracy. In the political arena they no longer held the power, the numbers, or the system of government. This had been lost to the tide of democracy which had completely changed the numbers, physical boundaries, classes, and loyalties of voters. The people had demanded more freedom, and obtained it. The House of Lords had managed to hold on to their position in parliament, but had had to adapt to survive. The political aristocracy was practically non-existent. The aristocracy as a class of people had also survived, but had also seen many changes, and not for the better. Their elite power and wealth had been whittled away; there was competition from the self-made gentry, formed from new money and the working classes. Peers had been created in great numbers, for political expediency, and because the idea of a title was something coveted by many, could now be purchased. The aristocracy had struggled through having been heavily taxed, and the agricultural depression which saw their land values and rental incomes drop dramatically while being left to cope with high interest rates on mortgages; leading to large portions land being sold off. Nudging from the government meant that much of this was opened up to the tenants, who were either not willing or not able to pay a great deal for the land. Throughout Great Britain the aristocratic landscape had been through much upheaval, and had settled back down looking much flatter where once they were the mountains, and while there was still another upheaval to come in the form of the Great War which would level the aristocratic landscape even further, the decline of the aristocracy by 1900 was almost complete.

image source

This essay was one I wrote as an assignment, while obtaining my University degree. I have included the reference list and bibliography - reference materials I used while writing - just as I’d had to for its submission. It has never before been published anywhere public, though. Images have been added for visual interest.

Endnotes

1 “The poem from which this stanza is taken, originally entitled ‘Aristocrats’, was written by Keith Douglas in Tunisia in 1943. It was occasioned by the death, on active service, of Lt. Col. J. D. Player…” as quoted in David Cannadine’s book The Decline and Fall of the British Aristocracy, p X.

2 “Originally, leadership by a small privileged class or a minority thought to be best qualified to lead. Plato and Aristotle considered aristocrats to be those who are morally and intellectually superior, and therefore fit to govern in the interests of the people. The term has come to mean the upper layer of a stratified group. Most aristocracies have been hereditary, and many European societies stratified their aristocratic classes by formally titling their members, thereby making the term roughly synonymous with nobility.” Aristocracy, retrieved 18 March 2010, from: http://www.answers.com/topic/aristocracy

3 Cannadine, David. The Decline and Fall of the British Aristocracy. London: Yale UP., 1990, p 104.

4 Beckett, J. V. The Aristocracy in England: 1660 – 1914. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1986, pp 468-9.

5 ibid., p 460.

6 Thompson, F. M. L. English Landed Society in the Nineteenth Century. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1963, p 8.

7 “The 1832 Reform Act was the most controversial of the electoral reform acts passed by the Parliament. The Act reapportioned Parliament in a way fairer to the cities of the industrial north, which had experienced tremendous growth. The Act also did away with most of the "rotten" and "pocket" boroughs such as Old Sarum, which with only seven voters (all controlled by the local squire) was still sending two members to Parliament. This act not only re-apportioned representation in Parliament, thus making that body more accurately represent the citizens of the country, but also gave the power of voting to those lower in the social and economic scale, for the act extended the right to vote to any man owning a household worth £10, adding 217,000 voters to an electorate of 435,000. As many as one man in five (though by some estimates still only one in seven) now had the right to vote.” From: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reform_Bills

8 “This extended the right to vote still further down the class ladder, adding just short of a million voters—including many workingmen—and doubling the electorate, to almost two million in England and Wales.” From: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reform_Bill

9 “Along with the 1885 Redistribution Act, this tripled the electorate again, giving the vote to most agricultural laborers. Only after 1884 did a majority of adult males have the vote. By this time, voting was becoming a right rather than the property of the privileged.” From: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reform_Bill

10 “It was a piece of electoral reform legislation that redistributed the seats in the House of Commons, introducing the concept of equally-populated constituencies, in an attempt to equalize representation across the UK. It was associated with, but not part of, the Reform Act 1884.

The Act made the following changes:

• Seventy-nine towns with populations smaller than 15,000 lost their right to elect an MP;

• Thirty-six towns with populations between 15,000 and 50,000 lost one of their MPs and became single member constituencies;

• Towns with populations between 50,000 and 165,000 were given two seats;

• Larger towns and the county constituencies were divided into single member constituencies

As support of the Irish members was needed by both major parties, the representation of Ireland in Parliament was not reduced, even though it had suffered a relative loss of population compared with the rest of the United Kingdom, due to emigration.” From: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Redistribution_of_Seats_Act_188

11 Cannadine, David. The Decline and Fall of the British Aristocracy. London: Yale UP., 1990, p 140.

12 ibid.

13 ibid., p 41.

References

Aristocracy (class), retrieved 22 March 2010, from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aristocracy_(class)

Aristocracy (government), retrieved 22 March 2010, from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aristocracy

Aristocracy, retrieved 18 March 2010, from: http://www.answers.com/topic/aristocracy

Beckett, J. V. The Aristocracy in England: 1660-1914. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1986.

Cannadine, David. Aspects of Aristocracy: Grandeur and Decline in Modern Britain. New Haven: Yale UP, 1994.

Cannadine, David. The Decline and Fall of the British Aristocracy. London: Yale UP., 1990.

Gentry, retrieved 22 March 2010, from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gentry

McCahill, Michael W. Order and Equipoise: The Peerage and the House of Lords, 1783-1806. London: Royal Historical Society, 1978.

Nobility, retrieved 22 March 2010, from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nobility

Redistribution of Seats Act 1885, retrieved 20 March 2010, from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Redistribution_of_Seats_Act_188

Reform Act Crisis, retrieved 21 March 2010, from: http://www.victorianweb.org/history/reform.htm

Reform Bill of 1867, retrieved 21 March 2010, from: http://www.victorianweb.org/history/polspeech/reform.html

Reform Bills, retrieved 20 March 2010, from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reform_Bills

Thompson, F. M. L. English Landed Society in the Nineteenth Century. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1963.

Thompson, F. M. L. The Rise of Respectable Society: A Social History of Victorian Britain, 1830-1900. London: Fontana Paperbacks, 1988.

Victorian Legislation timeline, retrieved 21 March 2010, from: http://www.victorianweb.org/history/legistl.html

Wilson, A. N. The Victorians. London: Arrow Books, 2003

Again, a very good picture drawn of the political decline of arustocracy. Thank-you. Considering the wars and upheavals, including invasions since the fall of Logres and the making of Anglaland, through fifteen hundred years of changing Royals and Religions, it is amazing that there were not more like The Earl of Athol with their own army. For most who only see the Bernard Cornwall series of Uhtred, the Island was always in upheaval or thinking about being so. Even the Royals after William 1, rarely saw a reign without some uprising. Since most of the original aristos came from being generals of war hosts or marrying their sons or daughters to families of such, that they were able to build enough peace, for the advent of their own downfall in the industrial revolution is a pretty good effort against the centuries it took. 😇

Thank you, yes very well put!

Calling @OriginalWorks thank you :)

Have you seen the @symphonyofechoes comp thing? Some of your essays might fit :)

No, I haven't, so I will check it out. Thanks ryivhnn! Much appreciated. :)

That's a lot of history you put down within your essay. You wrote a beautiful and well documented article.

As for the OriginalWorks bot I am not sure it works anymore.

Ah! I hadn't tried calling for OriginalWorks in a while. I shall miss its loving messages of support, lol.

Thank you for reading, I really appreciate it. :)

It is interesting that this gradual decline started with the French Revolution. Though I would speculate that it would have happened regardless (maybe not so soon). The Industrial and Agricultural Revolutions shifted the monetary power base and the entitlement of the aristocracy was bound to piss off the wrong people at the wrong time.

As always it was a pleasure to read one of your history posts. Looking forward to the next one. (I am going to read up on Continental European Aristocracy because of this LOL)

lol, should I be sending encouragement or apologies? ;)

While I was researching I kept circling back to the idea that this 'end of an era' meant that all the land wars up to that point over the centuries had all been rather pointless in the end. So much blood shed and so many lives wasted.

Perhaps, though, I should have been rejoicing in the fact that my agricultural ancestors finally caught a break, lol.

"All the land wars up to that point had been pointless" as opposed to land wars now?

I don't think the English have many land wars these days - at least not on English soil. No more storming the castle.