Using Archetypes: The Creator

The Creator is an archetype that focuses on bringing new things into existence; transforming reality by adding to it rather than taking away or transmuting existing elements. The Creator seeks to build a new reality, and in doing so they also embark on a voyage of self-creation and self-improvement, or fail because they do not recognize their internal needs or because they do not see the impacts of their creation on the world.

Background

For those of us just seeing this series for the first time, I'm writing a series on using Pearson's personality archetypes (affiliate link) in storytelling. This profile, of the Creator, is the eleventh of twelve entries in this series, following the Destroyer, Orphan, Innocent, the Sage, the Warrior, the Ruler, the Magician, the Caregiver, the Lover, the Seeker (https://steemit.com/tabletop-rpg/@loreshapergames/using-archetypes-the-seeker). You might also be interested in my earlier series on the Hero and Hero's Journey and the Nemesis.

If you just want a quick recap or introduction, here's the gist: archetypes are recurring patterns that have proven to be pretty universal. They're cognitive schemes that allow us to examine behavior and narratives in light of a coherent whole. That makes them valuable tools to audiences and storytellers, since they make stories authentic and lend them meaning.

Understanding the Creator

The Creator exists to bring new things into the world. The concept of the genius of the Romantic movement in literature and art, where the primary goal was to seek to achieve perfection in art through originality, matches up well with this theory, so many of the Romantic heroes and characters, most notably Victor Frankenstein, have high degrees of the Creator archetype in their persona.

The Creator is a product of their own minds–while they exist in the physical world, they operate in a world of dreams and ideals, much like the Innocent. The difference between the Creator and the Innocent is that they will not let anything come between them and the world they want to create, and they possess both the will and the aptitude to bring their dreams to fruition.

The Creator is capable of seeing beyond; they are no less mystical than the Magician or Seer, and may even be more enraptured by attempts to understand the fabric of reality. As God spoke the world into existence, they seek to bring to life the figments of their imagination.

This is a process that requires self-sacrifice and self-discipline. It is no less of an endeavor than fighting reality at its core and coming home as the victor, and the Creator's Hero's Journey often focuses merely on the tasks they need to do to get to the point where they can pursue their truest goal, which is changing the world.

Because they are so focused on changing the world, the Creator can also cause great benefit. They build cities, like Romulus and Remus, and found nations. The Creator's limitations are unhindered by reality because they understand that ambition and human drive can change reality. They find the missing piece that dooms the Innocent to folly and transform it into their source of transcendence: their own agency.

Creators push the limits in ways that no other archetype does.

The Creator is the Father and the Mother rolled together in union. It is rare because to become the Creator one must fully embody both elements; the desire to protect and the desire to nurture are not in and of themselves going to lead to the desire to create without being brought to fruition, and the Creator not only reaches the height of wanting to protect and nurture their creations but also creates for the sake of having a creation: for legacy.

The Tragic Creator

The problem that the Creator has is that they are very prone to losing their guiding compass; they are too focused on their new creation to consider the past, or even the present, in light of their grand schemes.

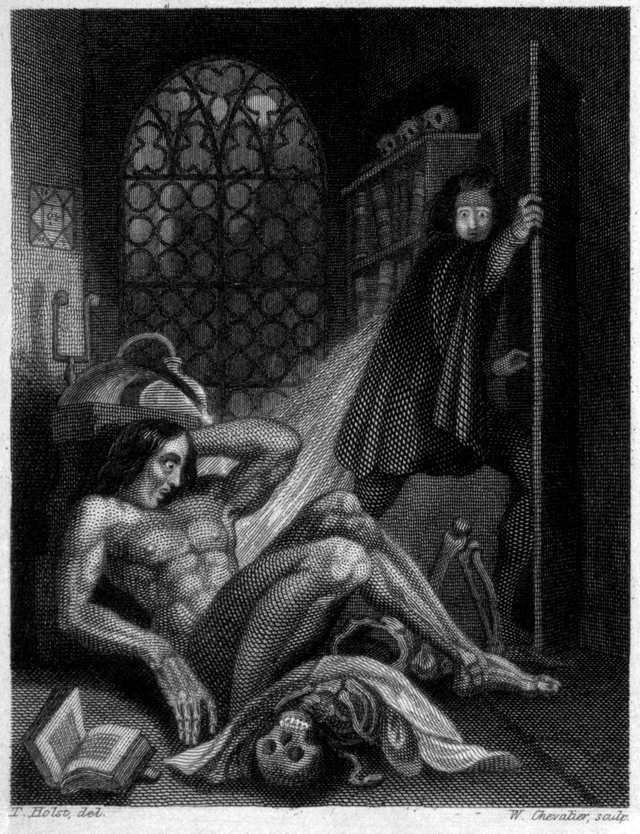

There is an obvious example of this to be found in Frankenstein, in which Frankenstein creates a Creature using scraps of cadavers. There are things that need to be pointed out in his methodology before any real examination of the text, namely the fact that he is doing something that is obviously unacceptable.

Frankenstein's fall doesn't come from the morality of his actions, however.

The Creator can be obsessed with becoming God, and they can never reach that peak. When they try, even in the most benevolent spirit–Frankenstein wants to create something better than humans, not only practically but also morally–they will be doomed to experiencing the Tower of Babel, the destruction of either their creation or the world they sought to expand through their act of creation.

In Frankenstein's case, this fall comes in the form of his Creature outstripping his master. Although the Creature has no knowledge of the secrets of the spark of life that consumed Frankenstein's academic endeavors, it is superior to him in intellect, physique, and even moral character in some senses. Frankenstein's Creature desires love–in pure platonic and common romantic forms–and is genuinely moved by the plights of others, while Frankenstein retains an air of entitlement and disregard for those around him, compounded by his inability to level with others following his poor decisions and weak mental fortitude that causes him to fail as a parent to the Creature and as a husband to his wife (who is killed by the Creature as a reprisal).

Image of Frankenstein with his Creature

The tragic Creator, as well as the villainous Creator, lacks the maternal and paternal instincts that come with the Creator's more fulfilled form. They create things that cannot have the environment they need to develop and blossom.

The Creator may also obsess, failing to create what is good because they are always seeking something better, experimenting at great cost to themselves and those around them–even at the cost of their creations. They have gifts and abilities that they turn after a fool's errand and end up unfulfilled and bitter.

The visions and dreams that dance in the Creator's mind can be their downfall as well as their greatest asset.

The Villainous Creator

The villainous Creator goes a step further than simply turning away from the right path. They actively reject it: in their own eyes, they are God and their creation is Good. There is no higher blasphemy than this, and the villainous Creator will create no end of misery.

Sauron in Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings trilogy is an example of a villainous Creator, building twisted races and foul citadels, he knows that his acts are destroying the world, but is willing to do so anyway because the destruction will leave behind ash that bears his image.

His most notable creation, however, are the Rings of Power, which allow him to control and influence the other races of Middle Earth by corrupting their noblest leaders. Intended to be a gift to the world, they bring only slavery and depravity to most of those who use them.

This sort of Creator not only creates without a nurturing environment for their creations to be raised in and without protecting their progeny, but also actively encourages a negative outcome for everyone: they cannot allow their creation to reach the point where it could usurp their power, but at the same time their creation owns them as much as they own it.

I believe that you can also see an end of inspiration in the villainous Creator (and occasionally in the tragic Creator), where their inspiration dries up and instead they begin operating in a dysfunctional manner, retreading old ground and devolving into grotesque parody. Instead of creating, they bumble and stagger through their endeavors and can no longer give birth to what they would have once desired.

Creators make things in their own image, and if they are debased then their creations will be loathsome.

The Creator in Star Wars

Although the core Star Wars franchise is somewhat weak on Creators–people will argue that Vader or Palpatine fill this role in some extents, with the former trying to build a new order with Luke and the latter building the Empire, neither really fit the Creator archetype as a dominant one.

However, in Rogue One we have the example of Galen Erso, who demonstrates many of the qualities of the tragic Creator. Part of an Imperial weapons project that yields the Death Star as its fruit, he flees and begins a new life with his wife and daughter.

This is an important part of the Creator's strong side: he abandons his life's work (the Death Star) because he realizes that it is both too dangerous to be brought into existence, but while still doing so he continues to serve in the role of the Father to his daughter. The Creator is often seen in responsible parents, who not only participate in the creative act of reproduction but in the duties that follow.

Prioritization of his family over the Empire also shows that Erso is a Creator with the maturity to avoid the Shadow of his nature, and while he is ultimately killed because of his decisions he manages to lay the seeds for the downfall of the Empire, succeeding in creating a better galaxy.

Using the Creator in Storytelling

The Creator is a powerful tool in storytelling. They are capable of sublime beauty and holiness like no other archetype: few can bring about a new future and new Being. Others simply transform the world around them, but the Creator adds new elements. They stand in direct juxtaposition to the Destroyer, who removes the corrupt and unneeded from the world.

A strong Creator looks for something that is needed, something that would make the world better–in a sort of mature echo of the Innocent's starry-eyed idealism–then does their best to bring it into fruition.

There is a powerful narrative to be had in applying the Hero's Journey to this quest. The Creator can be the ultimate underdog (I picture Will Smith's character in The Pursuit of Happyness as an example of this) coming from uncertain circumstances to triumph in the creation of a better world for themselves, those immediately around them, and everyone else in the universe.

The important thing to remember when considering the Creator is that they need to have some grand idea, and they need to have something that fulfills that idea. Plenty of weak stories have a Creator who fails to live up to their promise because their creation is flawed, but they do not tie this into any fault of the Creator. Instead the narrative becomes a manifestation of cosmic rage, the story of the Orphan rather than the ascended Innocent embodied in the Creator's dreams.

This can be a powerful tool–if done purposefully. If it is done accidentally, it feels cheap or unfulfilling, aborting the Hero's Journey at the Ordeal and creating an antihero.

Using the Creator in Gaming

The Creator fills holes in the universe, and this makes them particularly dangerous to bring into games. They can quickly put other characters in their shadow and steal the limelight, and there are unique mechanical difficulties in creating games that have a large existing ruleset and also encourage players to experiment with the Creator archetype.

There are a few ways around this. First, the Creator can have goals that are narrative in scope. A character who seeks to find the secret of life (akin to Frankenstein's quest) may find that they are able to do so, but the result is something that still functions within the rules of the universe. Barring that, you can create a game where the mechanics are fluid, or partially obscured, and the Creator brings them into a final state of revelation. This has the upside of potentially adding emergent systems that still bear the hand of clever design.

However, the simple thing that a Creator needs is some missing piece to fit into the puzzle of the cosmos. Many great stories can be told around this conceit, if it is approached from the right direction.

The Creator is the confluence of the Mother and the Father, so integrating them into a game is simple: let them make something to nurture and protect, fulfilling both those archetypes.

Wrapping Up

The Creator is the product of an imperfect world, trying to fill a hole that God left in the universe. While this doesn't necessarily require them to be blasphemous–they could be serving as a model to illustrate God's passion, or simply extending humanity toward a future where they can better serve the pursuit of goodness–it requires them to take on elements of the divine within them and turn it outward.

As a result, the Creator is second only to the Destroyer (and perhaps even greater than the Destroyer) in the amount of harm and suffering they inflict if they turn to evil, and their responsibilities and chances for failure are much greater than any other archetype's.

It's worth noting that the Creator can be an artist, but I chose to steer away from going too far down that path in this analysis because there's a lot of overlap with the Lover and the Fool down that road, and I don't want to create any ambiguity with that.