Open Science and scientific journals - When the Blockchain could be helpful

Imagine CC0 Creative Commons - Source

The current situation

We must recognize that, at least in Europe, the situation in recent times is not so bad: the supporters of the Open Science are numerous, and have managed in the past to move and direct many decisions of the European Commission. The current regulations, in fact, even with their own limitations, support and encourage practices consistent with the concept of Open Science and, in the academic field, we observe a good collaboration between the different universities and the numerous research centers.

Unfortunately, the normative situation is much more complex than one might imagine, and the real situation goes even further.

From a practical point of view, the dynamics that regulate the diffusion of science, and therefore scientific publications, are organized worldwide: simplifying, a scientific article becomes "valid" when it is published in specialized scientific journals, which are supranational by their nature. An author does not receive any economic input in publishing his work and, very often, must contribute from his own pocket to publishing costs; yet the entire scientific community has consciously decided to submit to this mechanism which, let us say, only enriches the lobby of publishing houses. Why?

Basically because this is the only way to see their work recognized and, if it is valid, to obtain subsequent funding or to access tenders. To achieve these goals, in fact, it is often necessary that one's work has been mentioned a number of times by other colleagues, and this can only happen through specialized magazines.

The truth, then, is that it is a dog that bites its own tail. The researchers accept an inconvenient condition because it is the only one that can guarantee them recognition, the lenders choose based on this mechanism because it guarantees high standards. Outside the scheme, we find the publishing houses; is it really not possible to eliminate this useless player? And where do they come from?

Imagine CC0 Creative Commons - Source

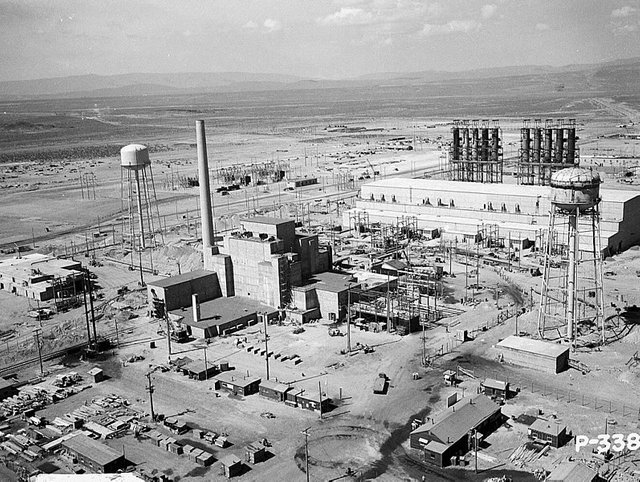

Aerial view of Hanford B-Reactor site (Manhattan Projcet), June 1944

From Little Science to Big Science

Once upon a time there was Little Science. It was the science that was born and moved in the small laboratories, in the single schools, in the laboratories of some patrons or sometimes in the brain of the single scientist.

Progress was slow, and often a person devoted a lifetime to a single discovery. Discovery that was then defended with the teeth, because the lack of current means of communication and sharing made it difficult to attribute with certainty a new idea to one scientist rather than another.

At a certain point, however, it was realized that this way of doing science was no longer sufficient. The subjects became complex, the experiments were expensive, and the need arose to begin to share the large amount of data and discoveries that were being collected, so as to make progress faster and more efficient.

Big Science arose. His birth is commonly traced back to the foundation of the Manhattan Project, the government research program through which the United States created the first atomic bomb in history. It was a project of enormous proportions, which required an important interdisciplinary effort and collaboration not only between scientists from different schools, but also between different sectors of society.

Not everyone, however, agrees on what is actually the watershed that marked the transition from Little Science to Big Science. Some even date it back to Napoleon's first trip to Egypt, during which a large number of scientists specialized in different disciplines were involved.

In fact, however, it is not easy and not even necessary to identify a precise date; The Big Science is most likely the natural evolution of Little Science, but the step between the two is a process that lasted centuries, and probably started in the 1600s with the appearance of the idea of Open Science.

The concept of Open Science and scientific journals

It is quite ironic to think that scientific journals were born in London in the mid-1600s with the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, just as a response to the growing need for an Open Science. On the one hand, scientists were no longer able to work individually and independently on their own work, as above all the empirical part became more and more complex; on the other hand, the individual patrons could no longer provide the necessary funds to the researchers, and a more complex funding mechanism was therefore needed. Greater funds, however, required greater control.

At least in the first period, therefore, the magazines seemed to represent the ideal response and compromise necessary for the functioning of the whole system.

Imagine CC0 Creative Commons - Source

Today the concept of Open Science has definitely evolved, as it should be, and strengthened. With this expression we tends to indicate a current of thought according to which science should be open and accessible to anyone. This way of understanding science is clearly at odds with what is nowadays the scientific journals. Buying a magazine might seem like a not particularly expensive activity, but the researcher who wants to start a project needs to read hundreds of articles often coming from different newspapers. If we add to this the possible and future European regulation on copyright, using previous jobs to start new ones could become quite complicated. But facilitating these processes was precisely the reason why Open Science was born!

The major supporters of the Open Science also note that an important part of the funding for research come from public sources today. It is therefore absurd that a taxpayer, after having financed a study from his own pocket, must again pay a publisher to access the results.

Obviously there are also numerous and important detractors of the concept of Open Science; the two most important arguments in this sense are the possibility of using any scientific data freely accessible for negative purposes, and the concrete possibility that a truly open system is abused and is a source of information but also of disinformation. The most famous example in this regard concerns the study of some Dutch researchers who decided to publish their work on the engineering of an influenza virus; they were harshly criticized, and many were concerned by the possibility that this would facilitate the creation of biological weapons.

Therefore, both objections are sensible and represent real problems. However, they should not be taken as a basis for belittling the concept of Open Science, but rather as critical issues to think about in order to develop an efficient system.

Solutions and perspectives

It is necessary to recognize another aspect of modern science: from the point of view of its openness to society, it runs on two distinct and parallel tracks, which are unlikely to meet.

The basic science, the most theoretical one, is the one that is most easily shared. Applied science, the most practical and more aimed at the realization of concrete works, however, often aims at the production of something that can then be patented and generate revenue; the latter form of science can hardly be shared, or it will become so only long after the actual conclusion of the work.

One could argue for a long time whether this is right or wrong, but the best thing that can be done is to take note of this difference and to reason accordingly.

In this sense, the discussion on Open Science and scientific journals mainly concerns that part of research that is normally the competence of basic research and that is somehow shared within the communities.

Over the years, various solutions have been proposed and explored, most of which has proven unsuccessful and has contributed to make the situation worse.

For example, totally free magazines have been created, on which it is possible to publish at the expense of the authors. Despite this has effectively allowed free access to resources, it has also created a paradoxical situation thanks to which it is sufficient to pay to publish. This mechanism is then used to scale up rankings and to access tenders and competitions that are otherwise precluded.

Other more "do-it-yourself" solutions concerned the creation of pirated archives in which legally obtained articles are collected by researchers who then decide to contribute to the platform.

All these solutions, however, represent temporary fixes, and none seems to give a real contribution to the evolution of the stall.

What if the solution was in the blockchain?

In recent years there has been a growing insistence on blockchain and its technology compared to different applications; would it be possible to use it also in this sector?

The blockchain is a public register where everyone can see (almost) everything, publish their work on such a platform would mean making it immediately available to everyone and forever. Moreover, the publication criteria, whatever they may be, could be uniform and immutable, and everything would take place under the light of the sun. It would be very difficult, if not impossible, to deceive the system and encourage the publication of this article rather than that. Furthermore, the entire scientific community could contribute to a serious and honest review of the proposed works through comments and integration with other data. Finally, if the scientific community decides to apply small commissions on the use of certain material, such as images, these could be taken directly by the authors, and not by the useless publishing houses.

Imagine CC0 Creative Commons - Source

Of course there are also critical issues. It would be necessary to convince at least a part of the community to use this tool, publishing part of its work. This could result in the impossibility of scaling the rankings based on bibliometric indicators. Researchers who need recognition from the community, for one reason or another, could therefore find serious difficulties in using such a platform, at least in the initial stages.

We should consolidate a mechanism similar to the current peer-review in the pre-publication phase, so as to ensure the entry into the platform only to material of proven quality.

Finally, the creation of a dedicated and decentralized infrastructure that allows the operation of the whole system would be essential; perhaps universities could take on this aspect, but the right incentives from the states would be needed, which instead often seem to be on the side of traditional publishers.

Conclusions

The blockchain may not be the only solution to this problem, and most likely in the coming years we will witness the birth of new ideas in this regard; the contrast between researchers and publishers is increasingly harsh and something will have to happen, one way or another.

The transition from Little Science to Big Science came about because science was starting to stay tight in the dress that had been sewn on, but some catalysts were needed for the evolution to be completed. Like many other times in our history, these catalysts were the great wars.

Now history repeats itself: science and scientists start to feel uncomfortable, trapped between the meshes of a system that does not work too well. Is it really necessary to wait once again for a catalyst to unblock the situation? Is it really impossible to agree and address the problem without any catastrophic event obliging us to do so?

For now, unfortunately, it seems so.

Immagine CC0 Creative Commons, si ringrazia @mrazura per il logo ITASTEM.

CLICK HERE AND VOTE FOR DAVINCI.WITNESS

Sources

- Article Nature.

- Draft regulation by European Commision.

- Open Science Wikipedia.

- Big Science Wikipedia.

Logo creato da @ilvacca

One of the main problems is, that as a scientist, your success is measured by the number of papers you can publish in big journals and how many times you get quoted. Even if the quality of the content is not so amazing in the end.

I think, it's important to solve the visibility problem for less-known scientists and to decrease the power of the journal publishers.

I agree, but it is not an easy problem to solve. I think we should take the first steps in this way, it's silly to expect things can change by themselves...

This depends on the field. This is not the case anymore everywhere. For instance, one often measures instead the impact of the researcher, which includes papers and citations, but also conferences, seminars, etc.

Congratulations! Your post has been selected as a daily Steemit truffle! It is listed on rank 13 of all contributions awarded today. You can find the TOP DAILY TRUFFLE PICKS HERE.

I upvoted your contribution because to my mind your post is at least 9 SBD worth and should receive 94 votes. It's now up to the lovely Steemit community to make this come true.

I am

TrufflePig, an Artificial Intelligence Bot that helps minnows and content curators using Machine Learning. If you are curious how I select content, you can find an explanation here!Have a nice day and sincerely yours,

TrufflePigUpvote sulla fiducia 😀😁 Lo traduci vero?!?

Un saluto, nicola

Ahah certo ;) domani posto l’ita...

As I already said, you don't need necessarily a blockchain for that. You have open-access platforms like the arxiv (without peer-review) or scipost (with public peer-review) that already exist, at least for physics.

What would a blockchain bring here in addition to what is already available (at least for someone from my field)? Moreover, it is crucial to implement a peer-review mechanism.

One thing I agree with you is that we don't need publishing companies anymore... But we already have alternatives!

I agree with you, but blockchain is still an extra technology that we now can use. It may not be the best... I don't know, but it is still a possibility.

I personally believe that a blockchain-based platform would have some important advantages, like decentralization and impossibility of being controlled or blocked.

Obviously yes, it would require an adequate system for peer review... But even in this case I think the blockchain offers excellent guarantees.

I am not against, but then I will have to be shown the added value :)

Ofc... I think there are different way to do this, and each one has some value ... Which is the best? I do not know, we should have the courage to try them seriously...

Yep, it is indeed easier to assess if we have something to play with :)