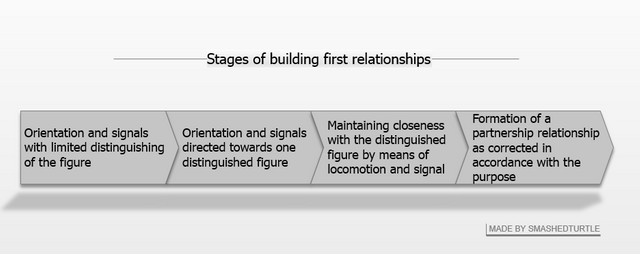

PSYCHOLOGY: Attachment: Stages of building first relationships

Intro

Bowlby (wikipedia)

First Stage

The first stage of attachment development is Orientation and signals with limited distinguishing of the figure. During this period, the ability to discriminate between people by a newborn is limited only to olfactory and auditory stimuli. This phase extends from birth to approximately eight or twelve weeks. If the conditions are not favourable, it lasts much longer. The behaviour of the child during its duration is manifested through the eyesight of the person to whom the child is oriented and reaching and grasping. When a child notices a face or hears a voice, he often stops crying. This behaviour affects the reaction of a particular person and thus allows interaction with her and the preservation of closeness. The intensity of these behaviours in a child increases around the twelfth week of life. This moment is adopted in a moment when the child "expresses a full social reaction with all spontaneity, vivacity and joy" (Rheingoid, 1961).

The second phase:

Orientation and signals directed towards one distinguished figure or several such figures is the time when the infant's behaviour is similar to that of the previous phase but is more pronounced in relation to the figure of the mother than any other. Differentiation of visual stimuli appears around the tenth week of life and is very unlikely to occur earlier. And for most children raised in a family environment, the differentiation of these stimuli becomes clear around the twelfth week. This phase lasts until the child is six months old, but may last longer, depending on the circumstances.

Third Phase

Maintaining closeness with the distinguished figure by means of locomotion and signals is the third phase of attachment development distinguished by Bowlby. It is a phase that begins between the sixth and seventh month of life, in which the infant grows in contact with different people more and more and extends the repertoire of his reactions, among others, following the mother who is moving away and using it as a safe base that allows exploration. At the same time, some people from the child's environment are selected for secondary figures attachment, and thus, friendly and undifferentiated reactions to others are weakening. Foreign people are treated by the child with increasing caution and later begin to induce withdrawal. In this phase, the existence of attachment can be noticed by each of the surroundings, because the systems that mediate the child's behaviour begin to organize in a manner subordinate to the principle of correction in accordance with the goal. This phase lasts with a high probability throughout the second and third year of life.

Phase four

The formation of a partnership relationship as corrected in accordance with the purpose is the fourth phase of attachment development, in which the child creates a cognitive map in the third phase of the child's maintenance of closeness with the attachment figure by means of simply constructed systems that are corrected according to purpose. Within it, the image of the mother appears, which is an independent permanent object in space and time and behaves in a predictable way. However, the child is unaware of the reasons for her behaviour and is unaware of what affects her approach and distance or does not know what she can do to influence these aspects. After some time, this condition changes and the child, while observing the behaviour of the mother and the factors acting on it, begins to draw conclusions about the goals, plans and ways of the mother = which she applies to implement them. This is the moment when the image of the child's world becomes more and more complex, and thus the "potential flexibility of its behaviour" gradually increases (Bowlby 1968). When the changes described above take place, there is already a foundation that allows building a partner relationship. This is the beginning of a new phase in both people's lives.

When can one talk about the existence of attachment?

Bowlby points out that adjudging on when a child is already attached is arbitrary. The author suggests that it happens somewhere in the second phase, but the assessment of when exactly this happens depends on how the concept of attachment will be defined by the evaluator.

Who the child chooses for his foremost attachment figure depends on who looks after him. Empirical reports prove that this person will be practically in any culture, mother, older siblings or father. Of these people, the child chooses the main attachment figure, which is most often the mother (Bowlby, 1968). If, however, for some reason this figure can't become it, this role can be taken over by other people who will behave "materially" towards the child. Other people may be children's playmates (sometimes it is a mother who is both the main figure of attachment), or secondary attachment figures. Although the child may have many secondary attachment figures, Bowlby (1968) considers the need for the child to have the main figure to be an important fact. A small child can't cope without a strong attachment to someone and longs for one particular person when it is far away. Therefore, the scattering of attachment to supporting figures does not mean that the significance of having the most important figure diminishes.

Ainsworth (feministvoices.com)

Research by Ainsworth (1982) and Rutter (1981) confirm the hypothesis put forward by Bowlby (1958) that a child has a strong tendency to direct his attachment behavior mainly towards one person, which the author calls "monotropy" and describes it as a universal one that has its own far-reaching consequences and implications in psychopathology.

Transitional objects and other attachment behaviours

Certain components related to attachment behaviour are directed not only towards people but also non-living objects. This is, for example, sucking, which does not involve the feeding of, for example, a thumb, and later a piece of material, a plushie, a blanket. The child then very much wants to take this item with him to bed and can expect his presence also during other activities during the day. In the studies of Schaffer and Emmerson (1964), they selected one-third of children who were clearly attached to an object that was soft. This usually occurs when the child reaches the age of nine months.

Winnicot

(psychoanalysis.org)

In his works, Winnicott (1953) draws attention to inanimate objects, which he calls "transient objects" and is convinced that they belong to the developmental phase, in which the infant begins his way to symbolization and thus these objects occupy a special place in object relations theory.

Literature:

- Bartholomew, K., & Horowitz, L. M. (1991). Attachment styles in young adults: A test of a four-category model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61, 226-244.

- Hazan, C., & Shaver, P. (1990).* Love and work: An attachment-theoretical perspective.* Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,59, 270-280.

- Kirkpatrick, L. A. (1999).* Attachment and religious representations and behaviour*. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (pp. 803-822). New York: Guilford Press.

- Sternberg, R. J. (1988). Triangulating love. In R.J. Sternberg & M.L. Barnes (Eds.), The psychology of love (pp. 119-138). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

SteemSTEM is a community driven project which seeks to promote well written/informative Science Technology Engineering and Mathematics postings on Steemit. More information can be found on the @steemstem blog. For discussions about science related topics or about the SteemSTEM project join us on steemSTEM chat.

Being A SteemStem Member

Interesting. And the parents also go though a kind of attachment Renaissance, learning to care once more, some saying they feel their life has changed. I wonder if after those 4 phases, we kinda forget how to be attached, and then we learn once more when we become parents.

It's also interesting that the child mainly attaches to one figure. I wonder how or if that relates to monogamy, whether we're wired to always care more about one person.

And I wonder what the Buddhists would say about this, seeing as they preach non-attachment! Which I consider, correctly it seems from this post, to be unnatural, and even impossible.