Substances as Salvation [Book and Societal Analysis]

As part of my steemit educational series, I am posting my previously written papers from earning my Bachelors in English Education and my Masters in Education Administration. The following paper was written as an analysis of The Revolt of the Cockroach People by Oscar Zeta Acosta. You might not recognize that name, but if you're familiar with Hunter Thompson and his book Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, Acosta is the Latino lawyer that travels with him during his time in Vegas. The book itself is about his father's time as an activist for the Chicano movement.

Source, Fair use

Drugs play many roles in culture. They have been demonized and outlawed as the corrupter of children, praised as the catalyst of the coup d’etat, and used for both recreation and medication. In literature, drugs are often compared to religion. By exploring this comparison, one will find a new mode of understanding the world and its possible future. Drugs are a powerful tool that can lead to the creation of a new society, one that is built around open acceptance of people who are answerable only to themselves and the relationships they chose to have with other people. This would require a reconstruction of society to allow personal responsibility for morals and actions, rather than the current police state which takes responsibility by making laws intended to protect people from themselves. This requires the state to cede control of life to the individual, despite possibly fatal mistakes the individual might make. Drug use and its consequences are a necessary consideration within a Utopian society. By thinking about the ways that drugs might be used within a society, one better understands the formation and continuation of culture, and the effect that will have on the continuance of the Utopian ideals.

Every religion requires a consensus in order to be dubbed a “religion” rather than a personal spiritual belief. Drug use creates a fellowship among users, which then creates a culturalization and exclusivity among the group. Chapter 14 of The Revolt of the Cockroach People begins with the two Acosta brothers sitting down to enjoy alcohol and marijuana together. While they discuss “la movida in East LA” they also “suck up our fat joints and blow smoke into the damp humid air” (Acosta 185-186). The girls, Betti and Anna, partake in both conversation and substances, even though they have just met Brown. One character, Sailor Boy, takes acid in prison and sees a picture of Brown. He tells his friends “If I ever get out, I’m gonna go see old Zeta” (Acosta 203). Sailor Boy felt a kinship for Brown, and becomes his bodyguard, without ever having met him. Even Gilbert, who was originally wary of accepting Brown (Acosta 35), comes to accept Brown after sharing beer, weed, and acid with him (Acosta 61, 64, 65). Drugs are a strong force uniting people of a similar mindset, no matter how long they may have known the other person. Brown reminiscences about his friendship with Gilbert and Pelon, “For years, the three of us have gotten drunk together, laughed and fought together” (Acosta 205). Drug use is similar to religion in that it creates a bond built on shared experiences between users. Collectively, it enables the group.

Drug sub-culture has existed since the 1960’s. Like any culture, including cultures centered on religion, it has a shared vernacular and symbology. Slang for drugs and drug paraphernalia is common among drug users. The words “trip” or “high” are used to describe the sensation of being on a drug. These terms have also crossed cultures into that of non-users within American society. Other terms, such as “snow” for cocaine, created the basis for new terms, such as “snow man” for cocaine dealer. During the development of Old English, church services were spoken entirely in Latin, thus creating a basis for Latin words to enter the lexicon. The majority of English speakers were illiterate, and thus could not read the Bible, making them fully dependent on their local church leaders for explanation and interpretation of spirituality. Slang serves in a similar way to keep outsiders ignorant and those in the know in charge. In any group, ignorance protects the status quo from being usurped by the underlings. Any culture has a hierarchy and wishes to protect it. In order to do that without an obvious show of force, they will use education to rise people they wish to remain within the upper reaches and keep those they do not in the lower limits.

This shared vernacular serves to denote users from non-users. Recreational users who know the slang automatically have a connection with other users in their communication, while those who do not know the slang will be labeled as a “narc” (short for narcotics officer, meaning someone who will possibly report them to the authorities) or at the very least a “noob” (usually a term used in technology circles to describe someone who has not had much experience, but also becoming a common term to describe anyone attempting something new). The ability to determine a “narc” from a true “stoner” is important in drug culture, as the activities within the culture are considered deviant and can get them arrested by the majority culture.

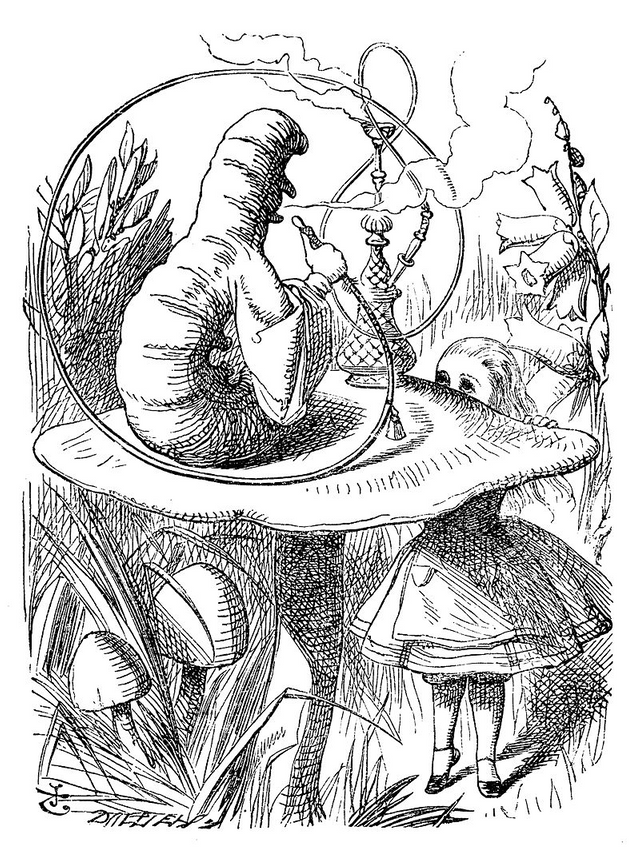

Another way to identify members of the culture is through symbols. The most recognizable symbol is the marijuana leaf or mushroom, used on clothing items or in art posted throughout the users home or using space. Other symbols may stem from stories that especially resonate with users. One such story is Alice in Wonderland, in which the Caterpillar smokes a hookah while seated on a mushroom. Images of Alice climbing into the “looking glass” or of the Mad Hatter can also be seen on the online image collection of acid blotter art on erowid.com. Other cultural symbols stem from musical artists who are known for psychedelic music, such as the Grateful Dead. Artwork originally designed for Grateful Dead albums has become iconic for people within drug culture, where images like the Dancing Bears and the Stealie Skull can be found on everything from jewelry, clothing, and other types of paraphernalia, like acid blotter sheets.

By Sir John Tenniel - “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland” (1865), Public Domain

There are various forms of art associated with drug use. From blown glass to acid sheets, drug users have their own religious iconography associated with use. Mark McCloud, an artist from San Francisco, collects blotter art in a gallery he calls The Institute of Illegal Images (Logan 4). McCloud was brought to trial twice on charges for distributing LSD on account of his illicit art. However, the prosecution didn’t take into account that “A museum celebrating blotter art is so blatant as to be perhaps the worst cover imaginable to distribute LSD” (Logan 3). McCloud was sentenced ‘not guilty’ on all charges. The fact that the symbology surrounding drug culture can be admired and recognized as art by those outside of that culture (such as a Kansas City jury) makes it a direct artifact of that culture. In interviews with McCloud, he calls LSD “the renaissance pill” because it has the ability to restructure society. He also compares it to religious observances;

The [active] content is right in the image, and it’s amazing how many people don’t notice the image when they ingest it. Now the predecessor to all this is the host, y’know… In a Catholic mass the host is made very much like blotter paper… blank sheets of bread are put into what appears to be a waffle iron and on one side is stamped an image of what appears to be the Holy Ghost – a dove flying through an electromagnetic field, and on the backside the name of the parish of origin. So I could have easily gone from parish to parish collecting hosts – but since they don’t work, anymore, I thought I’d collect the active host – the one that is bringing mysticism back to the people (McCloud)

McCloud believes that religion no longer offers people spiritual hope the way that drug use, specifically LSD, could. By comparing acid blotter sheets and their images to the holy sacrament, he is claiming they have similar powers. By consuming acid in a ritualistic way, one comes closer to the spiritual plane, just as consuming “the body” during the communion ritual is intended to bring Christ into the Christian, and allow him to work from the inside out. Acid, and similar drugs, change a person’s consciousness through the rituals surrounding their use. The act of consuming a drug with the intention of having a spiritual experience leads one to have that spiritual experience because of those expectations. In use reports on erowid.com, it is easy to note that people who are expecting recreational use get a recreational experience. The intensification of one’s experiences with acid can be seen as a reflection of society’s expectations for the user. Society expects users to be deviant, so they may become deviant against all odds and personal reasons. If society did not expect deviance from users, users would be less likely to be deviant.

Many within the culture see drugs as the prescription intended to cure all of society’s ills. What society lacks in morals and spirituality, will be returned through ritualistic drug use. According to Daniel Pinchbeck, in his book Breaking Open the Head, “... interaction with mystical realities was alienated from the masses and explicitly demonized” although “For many thousands of years, direct knowledge of the sacred was a natural and universal part of human existence” (Pinchbeck 22). Pinchbeck uses various psychedelics to achieve a connection with spirit that he did not find in his ambivalent religious upbringing. Aldous Huxley also found tripping to be a spiritual experience, where “The mind was primarily concerned, not with measures and locations, but with being and meaning” (Huxley 4). The rituals surrounding drug use are a natural extension of this spiritual experience. A government research study conducted through the National Research Council, however, reached a different conclusion. In it, they compare various rituals of controlled versus compulsive users, claiming that “without viable social sanctions which define limited use and are accepted by the group, the rituals either become empty, obsessive rites with no power to control use, or worse, become actual supports for compulsive use” (United States 209). According to their research, common rituals among users, such as that among psychedelic users to use only “in a good place at a good time with good people” are intended to limit use to a controlled level (United States 210). In the light of the comparison to religion, however, both theories have their place.

Religion is arguably a powerful force, leading to everything from wars that have torn nations apart to creating cultural centers that led to the expansion of literature through the known world. By including rituals within a religion, the religion serves to create a bridge between reality and the spiritual world, a bridge with protections built in to protect the common user. The spiritual world is generally believed to be powerful enough to influence both that realm and ours, and thus must be approached carefully and with great thought in order to acknowledge its power. Just as rituals protect drug users from becoming addicts, so religious rituals are intended to protect the believer. In the Catholic ritual of exorcism, sensationalized in movies, the Priest sprinkles holy water around the room in order to create a “blessed space” where he can do “blessed work”. This is similar to Pinchbeck’s experience, where “In shamanic cultures, the taking of entheogenic substances is always surrounded by ritual. A circle of protection is created, the four directions invoked, the spirits asked for their blessing through an offering of tobacco and prayer (Pinchbeck 142). Both cultures are using a substance as a sort of doorway into the spiritual realm, and both are requesting protection from the beings within that realm, through ritual. Ritual is intended to link ideas with action and, through repetition, create a habit of spirituality. Through ritual, there is an acknowledgement of something larger and more powerful then the human will and the human world that may be outside of normal conciousness. In drug culture, ritual creates a habit of controlled use as well as a type of spirituality. By insisting on following a ritual or tradition, users are elevating their use beyond recreation.

Any religion will have a defined space intended for sacredness. Christianity has cathedrals and churches; Islam has its mosques. Drug culture, however, tends to be defined by a return to nature, where the whole world is a sacred space in which to worship. In Acosta’s novel, Brown finds inspiration and courage on “Savage Henry’s blue acid” (65) in the desert with the other Chicanos. As they are getting chased off by the land-owners, Brown connects the occurrence with that of the Spanish invasion of the Aztecs. Rather than being frightened of the B-52 flying overhead, Brown chooses to “spit at the bird, flying at the speed of sound to kill brown babies and fine women and brothers that only want to pick up a chunk of earth and sift it through their fingers” (70). Being on acid gives Brown the clarity to connect the past to the present, the show of force to the enforcer, and strengthens his “commitment to the earth” (71). The references to the earth allude to the wish of the cockroach people to revert to a more natural, unfettered way of living. The Cockroaches are fighting against authority to gain rights that are theirs automatically. They feel that their revolution will create a world without the racism that plagues current society, and they achieve part of that through drug use.

Other places and events occur all over the world that are unofficially intended for users to temporarily live out their utopic dreams. According to Hakim Bey, quoted in an article by Dale Pendell about Burning Man festival, “The TAZ is like an uprising which does not engage directly with the State, a guerilla operation which liberates an area (of land, of time, of imagination) and then dissolves itself to re-form elsewhere/elsewhen, before the State can crush it” (Pendell 2). The TAZ (temporary autonomous zone) is an interesting concept in drug culture, as it allows for a public space where tenets rejected by larger society can flourish. According to burningman.com, “Once a year, tens of thousands of participants gather in Nevada's Black Rock Desert to create Black Rock City, dedicated to community, art, self-expression, and self-reliance. They depart one week later, having left no trace whatsoever” (“What is Burning Man”). At Burning Man, there is a rejection of commercialism and a creation of the “gift economy”. Nothing at Burning Man is sold beyond tickets to enter; everything is given away freely. In the middle of the desert, people are expected to bring everything they need, including water and food. This creates a new mode of relation between people, where one no longer asks “What can I get in return?” but “What can I give?”. This removes the hierarchy of provider and consumer, and creates a society that is far more equal in reality then any schemes of democracy. The insistence on a gift economy opens up a new system of values. By giving preference over what a person can give, rather than what they receive, there is less waste within the system of the society. Selfishness is frowned upon, rather than celebrated as it is in a capitalist society.

By Mike Q Victor - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0,

Another fascinating example of TAZ is 1969’s Woodstock. A significant and defining event of the 1960’s, Woodstock is a chance to see how people can come together in bad circumstances and “the youthful audience created for a moment a new ‘city on the hill’ emboding [sp] its vision of a loving and liberated society” (Eynon 103). Despite a venue that wasn’t complete, bad weather, and a massive overcrowding problem, the audience continued to cook foods and coffee for one another, while the locals were generous enough to share their bathrooms. The gates, because they were unfinished, eventually failed, and many people who didn’t have tickets were able to enjoy the show. According to one of the Woodstock participants, “As we crossed the line designating the concert to be free, a fresh breath of responsibility shed off the veil of commodity exchange based relationships and in return there manifested true love and respect for each other and the community that we were a part of (Douvris). George Douvris’ experience at Woodstock certainly sets a precedent for the experience at Burning Man and all TAZ inviting a new form of acceptance that is not otherwise available in current society.

Another tenet that drugs and religion share are they both require faith, even in the face of negative consequences. Religion is a distinctly human construct, and thus faces the same problems as all human constructs, including corruption. Drugs can just as easily be misused, both by the user and people with the intention of taking advantage of the user. Some of these problems stem from the structure of society itself in which the boundary delineating these two societal factions has, with the proliferation of psychotropic medication, been blurred to the point that with the exception of the floridly mentally ill, it has become difficult to know where mental health ends and mental illness begins. Without such a boundary, the whole of society becomes a potential community of deviance a global asylum, and all its citizens, residents. (Rubin 2)

This global asylum is set up similarly to a religious hierarchy. In order to obtain a cure/salvation, one has to approach an emissary, who will then ask a middle man to give one what they are searching for. Priests and doctors serve much the same function in American society- they are both highly educated circus masters who know exactly how to train people to jump through hoops in order to feel better about themselves. Rubin cannot resist the drug/religion analogy, and writes, “we readily walk through the gates of psychotropia, diagnosis in hand, heads bowed, and mouths open in eager anticipation of the host of psychotropic salvation” (Rubin 2). Current drug laws serve to separate people into those who obtain their drugs legally versus those who obtain them illegally, incarcerating those who may not be able to afford the middle man’s prices. Society does not expect its citizens to go without substances, but merely expects to be able to control how and why and how much someone should pay to receive them. The fear of addiction could be compared to reliance on a spiritual being; Why is one considered better than the other? Both require a person to give over responsibility to a human construct rather than accepting personal responsibility. In a Utopian society that requires a person to maintain their responsibility to themselves and to their relationships, minor drug use would not be frowned upon, but addiction would be.

It is easy to condemn those that one does not understand, but understanding can be achieved more readily through metaphor. By creating understanding where there once was suspicion, we allow for a utopian society that accepts everyone as they are and can possibly be, rather than valuing them for how well they fit into rigid standards. Our fear of drugs and the effects that they have on people is a reflection of our internal fears. What happens when a person lets go of control, not only of themselves, but of what other people do as well? If religion is a human construct, that reflects human values and traditions, then our current fear of drugs, which is also a human construct, must reflect human paranoia and excess. The limits of a utopian society that allows or even encourages drug use means that it allows for a certain amount of excess and lack of control. The utopian society cannot expect to dictate the how and why of a citizens use; The citizen can chose to use drugs for recreational or spiritual purposes, allowing for greater choice and new form of personal risks. By educating rather than creating laws intending to control citizens, utopian societies create a form of self-reliance that can be seen at TAZ like Burning Man. A society that outlaws drug use, essentially outlaws personal freedom and insists on strict control of a citizen’s actions at all times, while expecting society to regulate and retain responsibility for its members.

Drugs, like religion, are a powerful tool. They can be used to enslave or free people. Acceptance of drugs as a force, rather than demonization of it, would lead to a new society that would resist the hypocricy of denying people the world view of their choice. By exalting religion but declaring war on drugs, society creates criminals of possible priests and merely continues the cycles of discrimination that plagues it.

Acosta, Oscar Zeta. The Revolt of the Cockroach People. San Francisco: Straight Arrow Books, 1973. Print.

"Alice in Wonderland (Acid Blotter)." Erowid.com. Web. 10 Apr 2011.

Douvris, George. The Spirit Does Live On. Woodstock Preservation Archives. 2005. Web. 11

Apr 2011

Eynon, Bret. "Review: Look Who's Talking: Oral Memoirs and the History of the 1960s." Oral History Review 19.1/2 (1991): 99-107. Web. 11 Apr 2011.

Huxley, Aldous. The Doors of Perception. London: Chatto & Windus Ltd, 1954. Web. 8 Apr 2011.

Logan, Casey. "Adventures in Wonderland." The Pitch 19 Apr 2001: 1-5. Web. 10 Apr 2011.

“Mad Hatter (Acid Blotter).” Erowid.com. Web. 10 Apr 2011.

McCloud, Mark. juxtapoz, 6 Sep 2009. Intervew by Rak Razam. Web. 10 Apr 2011.

Pendell D. "Green Flames: Thoughts on Burning Man, the Green Man, and Dionysian Anarchism, with Four Proposals". The Entheogen Review. 2008;17(1):10-14.

Pinchbeck, Daniel. Breaking Open the Head. Three Rivers Press, 2003. Web. 8 Apr 2011.

Rubin, Lawrence. Psychotropic drugs and popular culture: essays on medicine, mental health, and the media. McFarland & Company, Inc., 2006. Print.

United States. Common Processes in Habitual Substance Use: A Research Agenda. Washington DC: National Academy of Sciences, 1977. Web. 11 Apr 2011.

"What is Burning Man ." Burning Man . N.p., 2010. Web. 10 Apr 2011.

Images are sourced within the post

Essay is property of Sunravelme