On Slavery (part two)

ON SLAVERY (PART TWO)

Slavery and racism

No essay on slavery can avoid talking about racial prejudice. After all, racism is often portrayed as being synonymous with slavery. But while there is no denying that an attitude of white superiority has existed, especially during the late 19th and early 20th century, we are wrong to suppose that blacks were enslaved simply because white racists considered them inferior. No, what actually drove slavery (or, at least, American slavery) was economics. Simply put, there was market pressure to secure cheap labour and profitable investments, and the commodity of slave labour just seemed a better deal compared to what was to be had.

As professor of Sociology, William Julius Wilson explained, “the conversion to slavery was not only prompted by the heightened concern over a cheap labour shortage in the face of rapid development of tobacco farming as a commercial enterprise and the declining number of white indentured servants entering the colonies, but also by the fact that the slave had become a better investment than the servant. As life expectancy increased...planters were willing to finance the extra cost of slaves. Indeed, during the first half of the seventeenth century, indentured labour was actually more advantageous than slave labour”.

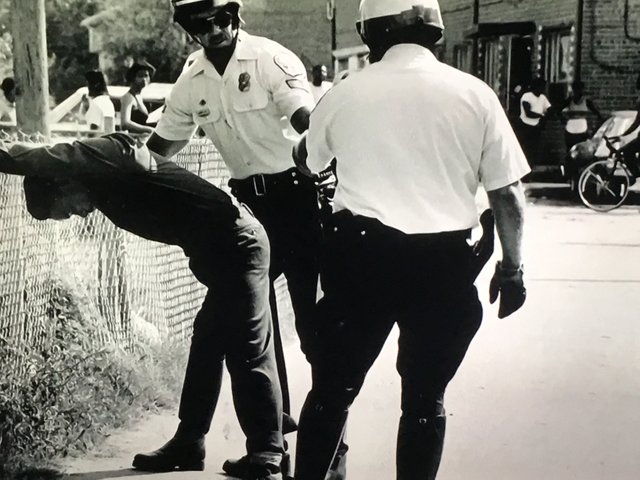

(Image from Storyville: Jailed In America)

That term ‘indentured labour’ is worth pondering. You may recall from part one how slavery is often portrayed as a violent theft of a person’s liberty (in movies, for example, there is often a sequence showing people being rounded up and physically forced into their new role as labourers or domestic servants). But a person did not always come to be in a position of servitude because others physically forced them into it. Sometimes people sold themselves into slavery. Now why on earth would anybody do such a thing? For the same reason plenty of people submit to employment. They are in debt and faced with likely punishment if it is not paid and so they ‘voluntarily’ give up their liberty and labour for others until the debt burden is lifted. In the case of 17th century indentured servants (and quite a few people today, actually) debts were so substantial it could take a lifetime in order to clear a debt, meaning little practical difference in such cases between an indentured servant and an outright slave.

I put voluntarily in scare quotes because I believe it is possible that, even though people who made such a decision may not have been physically forced into slavery, nevertheless there were other pressures which, if coercive enough, could have psychologically forced them into a life of servitude. In other essays I have referred to this as ‘negative motivation’, taking action not because you hope to be rewarded if you do, but because you fear the outcome if you don’t. For some reason free market ideologues believe that, once you legally grant the right of the individual to remove his or her labour, any deal involving the hiring of labour must be one that is free of any form of coercion and is voluntary in the true meaning of the word (“if they don’t like the deal being offered, they can walk away!”) It seems much more realistic to me that, rather than a sharp distinction between unfree slaves and employees whose decision to hire their labour is entirely volitional, you can instead draw a smooth continuum from the slave who is physically forced into servitude, to the indentured servant who is psychologically coerced into servitude, to the employee whose experience is a kind of ‘carrot and stick’ combination of rewards and punishment and so on up to the worker who regards his career as his true calling and does it gladly.

European indentured servants were not only practically similar to slaves. Attitudes toward them were also similar. As civil rights professor Carter A Wilson explained:

“Colour prejudice against Africans was rare in the first two-thirds of the 17th century. Legal distinctions between black slaves and white servants did not appear until the 1660s...Interracial marriages were common in the first half of the 17th century and...at this time they provoked little or no reaction”.

How slavery became racist

So, if market economics and not racism was what caused slavery, how did prejudice end up such a dominant part of the practice? It seems as though racism and class distinction was deliberately stirred up as a means of exerting control. Around the last half of the 17th century, expanded agriculture in Southern states created a huge demand for cheap labour, and that demand was answered by way of the global African slave trade. That also obviously meant a dramatic increase in population size. Thus, it was around this time that public policy began to change, with the intent to create security through hierarchical dominance. The invention of division between poor whites and black slaves was carried out in order to achieve the social distinction necessary for hierarchy. According to historian Edmund S. Morgan, for example, a government assembly in Virginia:

“Did what it could to foster contempt of whites for blacks and Indians...In 1680 it prescribed 30 lashes…’if any negro or other slave shall presume to lift up his hand in opposition against any Christian’. This was a particularly effective provision that allowed servants to bully slaves without fear of retaliation, thus placing them psychologically on a par with masters”.

The purpose of this prejudiced-based bullying was to ensure the growing slave population remained subdued and controllable. As Peter Joseph put it, it was a move to “generate a culture of bigotry and dominance that echoes to this day. So, in a sense, racism has effectively been a system reinforcer to optimise slave labour by way of sociological manipulation”.

Even after slavery was supposedly abolished, there continued to be an interest in controlling minority and lower-class populations. Segregation played an obvious part here, effectively trapping people in areas and circumstances where political and economic oppression were ever-present. As Peter Joseph explained, “the legal system morphed from direct racial oppression to indirect by targeting the outcomes of historical and present socioeconomic inequality, rather than any specific group”.

In other words, although in theory slavery has been made illegal in most countries, in actual fact societies were, and in many places continue to be, structured in such a way as to ensure a ready supply of labour that is not as free as we would like to believe. More on that in the next instalment.

REFERENCES

The New Human Rights Movement by Peter Joseph

Centuries Of Change by Ian Mortimer

To listen to the audio version of this article click on the play image.

Brought to you by @tts. If you find it useful please consider upvoting this reply.