Perception II

If I ask you what the All is, what would you answer?

Many people, upon hearing this question, would think about the universe, about planets, stars and galaxies, and about the greatest things they could imagine. However, all the answers of this type that could give are wrong, this is because they would be trying to imagine the All, and the All cannot be imagined.

This is mainly because we can only imagine images, and the All surpasses the visual and includes, of course, all types of perceptions, therefore, if we want to talk about the All we must encompass everything, without reducing ourselves to the use of only one of our senses, which is naturally absurd.

The second reason is that, when we imagine or think on the All, we place ourselves as external observers, that is, we in our head generate an image of the All and perceive the All from the distance, and that is impossible, because if we can perceive the All from the outside, then that is not the All, for there is something outside of it that is us, the observers. The All cannot be perceived from the outside, because there is nothing outside the All.

In the last publication we quoted the Buddha who insightfully said; "What is the All? Simply the eye & forms, ear & sounds, nose & aromas, tongue & flavors, body & tactile sensations, intellect & ideas." This is, of course, perception.

Quickly reviewing the interpretation we gave to this was the following; The fact that he makes a separation between what perceives and what is perceived indicates, in the first place, that he refers to the subject (eye, ear, nose, tongue, body, intellect) and the object (forms, sounds, aromas, flavors, tactile sensations, ideas). On the other hand, the fact that he includes the intellect in the same way as the sensations indicates that he does not make a separation between sensible objects or material objects and ideal objects or ideas, this is especially important because in this way breaks the dichotomy idealism-materialism.

In addition, the Buddha concludes by saying; "Anyone who would say, 'Repudiating this All, I will describe another,' if questioned on what exactly might be the grounds for his statement, would be unable to explain, and furthermore, would be put to grief. Why? Because it lies beyond range."

Although we will go step by step. Here is the link for the first part, that although it is not completely necessary that you read it, it would help to better understand everything that will be said from now on. Although two things should be remarked mainly; the particular meaning we are giving to the word "perception"; and the particular non-Buddhist interpretation that we are giving to a Buddhist discourse.

Do you know what it means that there is subject and object? Let's say the obvious and see the consequences.

Have you ever seen your eye? And don't think that I mean that if you have seen the reflection of your eye in a mirror, or in the water, or in any other thing, but I mean that if you have seen your eye directly. You've done it?

Of course not, it's impossible, because what perceive and what is perceived are always two different things, this is the direct consequence of admitting the subject and the object. You can't see your own eyes, smell your nose, hear your ears, and so on.

Look at the problem that is presented to us now, if what perceive and what is perceived is always different, how is it possible that we perceive what we perceive? that is, how can we perceive our perception? I hope this is understood.

Because we have been talking all this time, not only of the vision, not only of the sensation, and not only of the intellection, but we have been talking about all of them together, and if we have been talking about all of them together, it is necessary that we perceive all of them and we can notice the difference between them, so that we say that they are different things and we don't believe they are the same.

Through seeing we only perceive colors, through hearing we only perceive sounds, through smelling we only perceive smells, through taste we perceive flavors, through touch we perceive tactile sensations, and through intellect we perceive ideas. However, by what means do we perceive these perceptions?

This is the origin of the whole problem, since just as we know that what we perceive is not the same as the perceived, we realize that we can't perceive what it is that perceives our perceptions, since if we perceive it, we should ask ourselves then; what finally perceive this? And so on ad infinitum.

It seems that we don't perceive the origin of our perception, which is absurd if you think about it, because we are precisely the origin of our perception. Or is not it? We, ambitiously, wanted to perceive the All, and now, however, we realize that we don't perceive ourselves.

Now, if I ask you, is it possible to know what has not been perceived? That is, for example, as with an apple. Can someone who has never seen, smelled, tasted, listened, touched or thought of an apple, know what an apple is? Evidently not. Knowledge derives precisely from having perceived something in the past, and having the ability to remember it and keep it in our mind. Knowledge really is nothing other than remembering something that has been perceived before.

It seems that if we can't perceive ourselves, we can't know ourselves either, ergo, we don't know ourselves. Or so it seems until now.

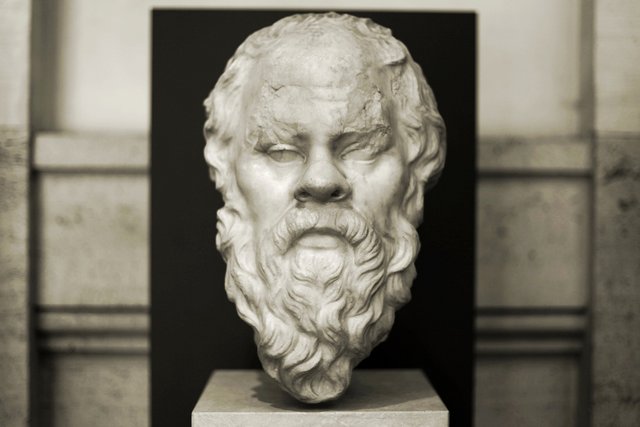

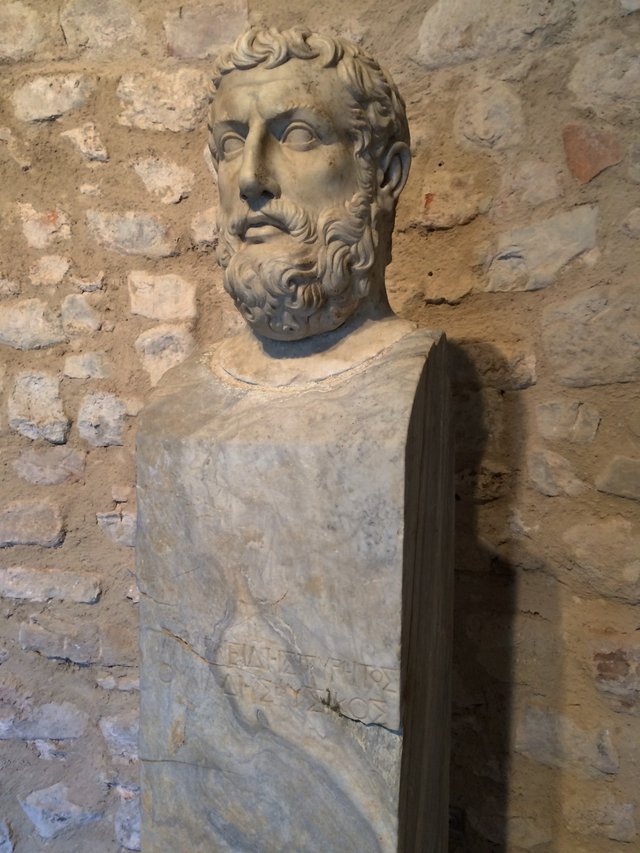

You know what? I believe that this Delphic maxim, "know thyself", is one of the wisest things, and perhaps it is even the best philosophy of life, or better yet. In fact, I believe that the best knowledge that is possible to acquire is not that of any specific subject other than ourselves, I believe that the knowledge of ourselves is the most important of all.

Have you not noticed that every time we study well, anything, we learn more about ourselves than about the object of our study? That is, as when we think we know something, but then we investigate more about it, and as we acquire new information we realize that, although we know more, we are also more aware of our ignorance. It is a fact, in my opinion, that people who know very little, always believe that they know a lot, and people who know a lot, know that their "a lot" is very little..

This is because when we know little, we only know what we know, ha, but when we know a little more, we not only know what we know, but we also know what we don't know. For this reason I firmly believe, perhaps I'm wrong, that the full awareness of our ignorance is the highest degree of wisdom.

But wait a moment, we have not said that to know something it is necessary to perceive it first? How is it possible that we know ourselves, or know our ignorance, if we can't perceive ourselves?

This is because we can perceive our reflection, we can see the trace we leave in everything that surrounds us, in our entire environment. We are like the sun, which illuminates everything around us and permeates with light everything that comes close to it. If this bright star had a pair of eyes like us and come alive, it would be astonished to see how all the planets, satellites, and space rocks illuminate with a strong glow, believing that each of these things that see are themselves brilliant. The sun does not know the dark side of the moon, nor does it know the night, because it is only able to see what it illuminates. However, when the sun receives the insight we have and carefully examine what surrounds it, it will realize that it itself is the source of light, and that space is dark when he does not illuminate it.

But let us dedicate ourselves for a moment to sustaining what we have said, because our mind is not nourished only by allegories, and although we can (or not) intuit the truth of what has been said, we must understand it so as not to forget it. For if knowing is like remembering, as we have said above, and forgetting, therefore, is not different than ignoring.

Above I asked; Have you ever seen your eye? And the answer was a resounding no. But if now I will ask you if you know what your eye looks like, what would you answer?

You would probably say yes, because you have seen the reflection of your eyes in a mirror. You have perceived the reflection, and you have the knowledge of the reflection. Should we say that you know what your eye looks like, or rather that you know what the reflection of your eye looks like? If tomorrow we discovered that all these years the mirror has deceived you, and that the reflection that you see there is not you but another person; Would you know who you are?

In effect, you don't know what your eye looks like, you know how the reflection of your eye looks, and it is important to make a distinction here because one thing is what we are, let's say essence, and something else is what we seem to be, let's say appearance. That reflection that you see in the mirror is not you, it is something similar, it is something that looks like you, and which we use to perceive our physique, but to believe that what we see is us is the first externalization we do, to believe that we are something alien to ourselves, the same as the sun that believes that the one that shines is not itself, but the planets that it sees.

Now, you perceive your reflection and know yourself, as long as you understand that you are not the reflection (appearance), but the origin of the reflection (essence). But it seems to me that for the type of reflection that we seek to see here, a common mirror will not be enough, because in this case we don't want to perceive our physique.

Look, I think that humans have a certain "obsession", to say it somehow, with ourselves, in the sense that we are constantly pursuing our own reflections in search of perceiving ourselves, indeed, we meet with similar people, when we see people who share our opinions, our worldview, in short, when we see people who perceive things in the same way that we do, then we get closer.

Birds of a feather flock together.

The reason for this, in my opinion, is that we have an insatiable interest in knowing ourselves, and when we see similar people an immediate reminiscence takes place, when we perceive that that person is similar to something but we don't know what, because it is similar to ourselves. This is so true that when you study body language there is something called "mirror images" or "mirroring", which refers to the behavior that people have when meeting someone like them. It has been observed that close people, be they friends, spouses, or people at the same status level, tend to imitate their gestures and postures unconsciously, because in this way both show that they think and feel the same.

Here we have the mirror we are looking for. To perceive ourselves we must be empathic and see what we have in common with the people around us, in such a way that we learn from ourselves by collecting information through others that resemble us.

However, we also need to know our appearance, and I am not talking about physical appearance, but of the appearance that we have to the others, that is, what other people think we are. It is important that we do it because, although we are not such appearance, we are the origin of that appearance, and therefore, it is linked in some way to us. We do this when we perceive how others perceive us. That's right, when we try to perceive the perceptions of others.

In this way we see how other people react to us, and abstract from here the way they perceive us. But since nobody perceives things in a perfectly objective way nor in a completely subjective way, as we have tried to show in the previous post, but our perception is a bit of both, then only a part of what others perceive is us. It is evident that the people who love us tend to idealize us and that the people who hate us will tend to lower us, however, there is some objectivity in both visions. We seeing ourselves through their eyes, both those who love us and those who hate us, can perceive us in a fairly objective way, if we are perceptive enough of course.

For it is necessary to be perceptive, intelligent and sensitive, because both forms are necessary, and will help us in this undertaking, contrary to the fact that each one separately far from benefiting us will be harmful, causing us to externalize and believe erratically that we are, not the origin, but the reflection.

On the one hand, those who perceive themselves only by seeing themselves reflected in others, that is, in a subjective way, they end up believing, as many in fact affirm, that "we are our environment", which will cause an attachment with each one of the things and people that surround us, because in effect, if we believe that we are our environment, we will not want to change it for fear of lose ourselves, denying the inherent change in nature and clinging to all kinds of things that we should not cling to. We are not our environment then, although our environment is a faithful reflection of us. We are the reason for our environment.

On the other hand, those who perceive themselves only through others, seeing themselves reflected in the perceptions of others, end up confusing their essence with their appearance, ignoring and placing themselves at the mercy of others, taking as absolute truth the opinion that everyone has about them, when in fact it is not more than that, opinions.

But both forms are necessary. When we perceive our reflection in all others, we perceive ourselves in a subjective way, and we notice the change around us, understanding in this way that we are the center of the All, since everything we perceive revolves around us. But in turn, by perceiving our reflection through others, we perceive ourselves objectively, and we understand in the same way that we are the ones that revolve around everything else, and that our environment changes precisely because we change, to conclude definitively that just as everything we perceive revolves around us, we revolve around what we don't perceive, and only on the basis of these two perceptions can we finally know ourselves, and of course, know the All.

Maybe I should explain myself better, because I think this finally sums up my interpretation of what Buddha has said. The All is not only what we perceive in a subjective way, as when we do it with our sensations, nor is it only what we perceive objectively, as when we do it with our intellect, the All is not only the subject that perceives or only the object that is perceived, but the All is precisely the union of all these things, when we understand that, just as we act as subjects because we perceive, we also act as objects because we are perceived, without ever being any of these things, breaking this dichotomy contradictorily, and realizing that we are part of an ecosystem which gives, receives and works in a harmonious and reciprocal way.

The All is not only the truth or the relative to the object, but also the opinions, the subjective perceptions, the falsehood and the appearance.

Someone will say; But what?! Breaking the subject-object dichotomy, don't we develop all this argument based on precisely that?

Of course, but the subject-object dichotomy only exists as long as there is perception, because for it to exist there must always be two things, one that perceives and another that is perceived, and if we need to perceive ourselves, there can only be one cause, and it is that we don't know who we are. As we don't know who we are, we make a division of ourselves and we externalize it in order to perceive ourselves, in the ways we mentioned before, believing that we are two things at once and not one, which is a gigantic mistake, and this is the reason why one should seek to transcend such perception. The perception of ourselves of course, to finally reach the knowledge, again, of ourselves.

The speech concludes; "Anyone who would say, 'Repudiating this All, I will describe another,' if questioned on what exactly might be the grounds for his statement, would be unable to explain, and furthermore, would be put to grief. Why? Because it lies beyond range."

This is because there is no other All that can be described, since there is nothing that we can perceive when we transcend perception. This is what the Buddhists refer to, in my opinion, when they speak of "emptiness" as "ultimate truth", that is, of the lack of something to perceive, since it is no longer perceived, but is, or in other words, we no longer perceive, but we are. This is also the reason why they describe nirvana, not because of what it is, because it is not perceptible, but because of what it is not.

At the beginning I said that the All cannot be perceived from the outside, from where can it be perceived then? From nowhere, the All is not perceptible, because to perceive there must be two things, object and subject, and since there is nothing outside the All, the All is imperceptible. In addition, we ourselves are part of the All, and to want to perceive the All is to commit the same mistake that to want to perceive ourselves. This is why the Buddha says that the All is perception, for that is the only All that can be described.

This is the reason and the final cause of everything; self-knowledge, therefore, when we don't know who we are, we must perceive our reflections to know ourselves, and when we have achieved such a feat, which is nothing more than remembering what we had forgotten, then we must finally do the same with the All, to simply realize that all is one, and we are a part.

All this of course, if we accept the premises that we have established, which are not carved in stone and therefore, may be wrong, if you notice that it is so, I would be immensely grateful to be corrected.

All is ended.

The All is the coder writing the code to make it all work here.

To sheep the All is the devil in this word controlling reality through TV, radio and newspapers because that is all they know.

To an insect the all can be your backyard because he is born there and will die there.

Yes, I cannot perceive the All because that would mean I am outside of it and therefore it cannot be the All but divide 1/10 and you get 0.1 now do it for 1/1000 you get 0.001. now do 1/100000000000000000000000000000... At some stage we get so close you can call it 0 even though it is not 0 - :-)

Perhaps everyones All is not all but for some it is pretty damn close. Perhaps the answer should be it depends on who is looking at the answer.

Ag please @lyfie. Bugger off... That was my comment lol!

Excellent post. A lot of chew on obviously but I wanted to post my thoughts on this excerpt

It is a fact, in my opinion, that people who know very little, always believe that they know a lot, and people who know a lot, know that their "a lot" is very little.... For this reason I firmly believe, perhaps I'm wrong, that the full awareness of our ignorance is the highest degree of wisdom.

You are not wrong here. Now let me preface by suggesting that we lower the bar from understanding the All, to Mostly Everything. From there, we have some framework for understanding ourselves because knowing the All as you have said, is impossible.

As humans, our powers of perception are great but not omnipotent. Sometimes we are correct and most of the time we are wrong. Even with a lifetime of training, we can only come out with a very small fraction of the "Mostly Everything".

Those who boast about knowing Mostly Everything are clearly full of it. And everytime one does, ask yourself why their powers of perception have not manifested in a more desired quality of living.

Ignorance to them is something that needs to be compensated for instead of embraced. That is why their development will cease (because they cannot perceive beyond what their ego allows them to see) while the development of the ignorant continues to have near limitless potential. So the "smart" one is destined for a life of inner frustration because he does not know himself. And does not know what makes him happy.

When I mention "the All" I refer to the ontological all, that is, everything that exists, absolutely everything. The reality itself. Although now I see that it can generate confusion especially the part of knowing ourselves.

Although I agree with what you say, by the way. Ignorance is not good, but the knowledge of our ignorance is.

Congratulations! Your post has been selected as a daily Steemit truffle! It is listed on rank 6 of all contributions awarded today. You can find the TOP DAILY TRUFFLE PICKS HERE.

I upvoted your contribution because to my mind your post is at least 4 SBD worth and should receive 261 votes. It's now up to the lovely Steemit community to make this come true.

I am

TrufflePig, an Artificial Intelligence Bot that helps minnows and content curators using Machine Learning. If you are curious how I select content, you can find an explanation here!Have a nice day and sincerely yours,

TrufflePigI think this text of yours I can describe best as a "science poem". It was a pleasure to read. A masterpiece of yours.

Nearing myself the statements of what the Buddha said and what you explain here, I thought about "myself" and realized that I started to feel careful in the presence of people and try to avoid to label them as this and that. When I talk to friends and I say something like "you are an artist in your heart", it sounds kind of awkward to me and almost like a lie as I instantly think that even though there is truth to my observation this cannot be the full truth.

Also, when a friend tells about him/herself "I am a hypersensitive" I feel that even though I perceive it as true, at the same time I reject the totality of this perception of the self of my friend.

Sometimes this causes an inner conflict with me and then I try to stay in this realization that both is correct for the time she or he talks about. People always refer to a certain moment in time but then mistake it as something solidly built in them.

This underpins what you say about clinging to the perception and it's interpretation as something one doesn't want to lose.

Even this "essence" is not there as an entity, as the doctrine says, but to make one understand we need this term in order to understand all the other terms.

One of the most difficult things to experience is the strangeness of perceiving oneself. There is something inexplicably frightening about being alone with oneself in silence and facing this foreignness.

As a child I experienced such moments, but not as frightening, for example playing hide and seek under the blankets that we children had spread over the whole floor and hid underneath in the darkness. For very brief moments, I was struck by the absolute otherness and unreality of this situation. The best way to describe it was to have the feeling that I didn't exist under the table. Not for fear of not being found, because I knew they would find me. It was like a brief flash of a truth that I neither questioned nor analyzed at the time, but merely felt. At that moment I had learned that I was not myself and that I had met someone/thing absolutely foreign.

Fantastic. The Buddha showed an intelligence (or has been used for the intelligence progression of the Buddhists) that meets modern standards. ... Or ... just something occasionally shines through humans which try to understand that they don't know anything.

All this can be quite confusing.

To integrate this kind of knowledge in ones life, I guess, the 8full path is a clever one. I haven't made up my mind though.

Thank you for sharing this thoughts of yours. Did it all come out in once?

"Sciencie poem", that sounds like a very good way of say philosophy.

The words are immensely powerful. After you express something that is always there in your head. It is a way to "immortalize" something, so to speak. That's why we have to be careful with the judgments that we made and expressed, and is for this that I always try to make it clear that "maybe I'm wrong" or that "it is not carved in stone", although I don't really believe that that works a lot.

The truth is that if you say that a person or a thing is in such a way, every time you see it you will be looking to confirm or refute that judgment.

The Orientals say that there is no essence, they are speaking in a subjective way, in the first person, and since they can't perceive the "essence", they don't see the usefulness of the term. Westerners say that the only thing that exists is essence, they are speaking objectively, in the second person, and although they don't perceive the "essence", they refer to it as what perceive. The first say that everything changes, the second that nothing does, even so, both are right. At least I think so.

Ha, that happened to me, it's like a disconnection. Although you describe it better.

For my scale it is the other way around, I see the ancients much more intelligent than the moderns, at least in these matters.

Yes it did, but I forgot it. Then I tried to remember it and I could not. So I started writing it without remembering it and I remembered it little by little. In the end I remembered and I started it again.

Thanks to you for stopping by, and for the kind comment, as always, greetings.

Interesting information:

I did not hear that in this clear distinction. I listen a lot to the statement that there is no "essence" and I like to play with that thought. It causes me more interest then the Westerners saying. It reminds me on the ongoing argument between a good friend of mine and me and this is exactly the "dispute". Laughter! I know, both are right. It finally dawned on me.

Glad that you can confirm this experience, too. Any details about it? :)

That made me laugh! I find it really amusing how you describe here your writing process. Been there, too.

Sorry. Only vague memories.