Nonprofit Mismanagement: Financial Literacy Does Not Equate to Good Financial Leadership

90%

This seems like a sizable proportion doesn’t it? That’s just shy of a perfect 100%. According to a study in 2009 from the Technical Development Corporation (TDC) commissioned by the Pew Charitable Trusts and William Penn Foundation, 90% of nonprofits in Philadelphia’s cultural sector are financially literate. More than half of them were considered “highly knowledgeable.” In other words, almost all of Philadelphia’s cultural nonprofits, its museums, art and performance organizations and so forth, have an understanding of finance, how to budget, and how to handle their money. Furthermore, this financial literacy “did not vary significantly by budget size, discipline, or financial health.”

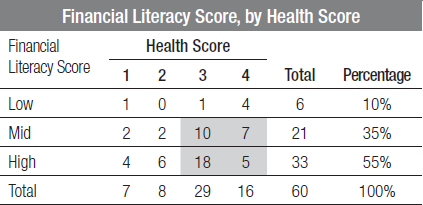

- Table from TDC's 2004 study, Getting Beyond Breaking Even, on page 6. The numbers 1 through 4 indicate a nonprofit's financial literacy from 1 (the strongest) to 4 (the weakest). In the mid- to high financial literacy rows, combined you can see that 90% percent of nonprofits are financially literate, and 55% are highly so.

This same study published in 2009 indicated that 77% of these nonprofits are financially weak, that is, they are struggling economically and to budget properly. There was little variation based on budget size, but the TDC did note that those at the very top (those with budgets of $20 million or more) were slightly financially healthier and that those at the bottom (roughly $150,000-$250,000) tended slightly towards poor financial health. But again, the overall, big picture here was that 77%, a little more than three-quarters, of Philadelphia’s cultural nonprofits are financially weak.

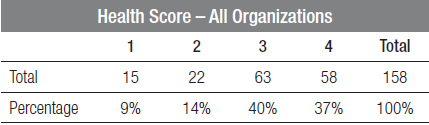

-Table taken from TDC's 2009 study, Getting Beyond Breaking Even, on page 6. Once again, 1 through 4 indicates the strongest (1) to the weakest (4) financial health among nonprofits in Philadelphia's cultural sector. As you can see,

77% are designated a 3 or 4, indicating financial weakness.

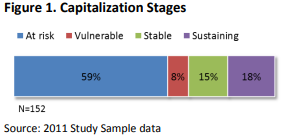

What gives? Wouldn’t one assume that with sufficient knowledge of finance and one’s own organization one could pinpoint the problems and correct accordingly? To make matters worse, the TDC conducted a follow-up study in 2014 which yielded similar results: “Organizations remained undercapitalized with approximately 70% meeting our criteria for poor financial health.” Worse still, they found that the financial distress had deepened, finding that “the total amount of negative available unrestricted net assets in the system grew from negative $14 million in 2007 to negative $25 million in 2011.” And to be clear, there was no indication in this study that financial literacy had changed since 2007.

-This graph is taken from TDC's 2014 study, Does Growth Equal Gain? on page 9. This graph it indicates that 59% percent of Philadelphia's nonprofits in the cultural sector are "at risk," and that an additional 8% are "vulnerable." This means that roughly 70% of nonprofits remain financially weak enough to be considered either "at risk" or "vulnerable."

The 2014 study suggested that one of the reasons financially weak organizations remained as such was because they lacked the capital to take risks or invest in change. This is a fair answer. In times of economic transformation, and transformation within an entire market, extra money is needed to fund change. At the same time, I see no reason why they could not restructure their budgets to play to their strengths until such possibilities arose. Even in the 2009 study, the TDC noted that “most organizations can identify their key capitalization issues, they have not been able to integrate this knowledge into coherent plans that tie to a comprehensive and contextual strategy.”

This frustrates me greatly. You can identify your key issues but cannot act accordingly? A quote from one of my favorite drag queens, Trixie Mattel, comes to mind: “If a building’s burning down and you couldn’t find the exit, honey you didn’t want to live anyway.” If you can identify your problems but do nothing to rectify them, you didn’t want your nonprofit to survive. Of course, I say this tongue in cheek. This is not constructive. The bottom line is this: if roughly 70% of nonprofits in Philadelphia are financially weak, recognize their problems but cannot or will not resolve them, a significant change is required. I furthermore see this as a problem among the cultural sector's leadership generally, and I'm not the only one.

In her recent article on Laura Raicovich's resignation as the Queens Museum's president and executive director, Robin Pogrebin describes the serious disconnect between those running museums and the museums' Boards of Directors. In Raicovich's case, after three years in charge and proposing innovative ways to collaborate with other institutions and address with social issues, and several brilliant exhibits that doubled the Museum's fund-raising capacity, she resigned. Why? In Pogrebin's words, "While directors hold the artistic reins of a nonprofit institution, they ultimately serve at the pleasure of their boards, which tend to shy away from political controversy." Laura Raicovich is not alone in resigning in the face of conservative boards. Lisa Freiman, the former director of the Virginia Commonwealth University's Institute of Contemporary Art in Richmond, and Olga Viso, former executive director of the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, are two other examples of cultural institution leadership who walked away due to restrictive Boards.

So what are we to do? Whether due to a refusal of engaging with relevant, social issues by the Powers That Be, or inexplicable financial weakness, institutions in the cultural sector are failing financially. I am, admittedly, not economically-minded enough to provide solutions, but one of my classmates and colleagues is.

-Comic by OwlTurd.com

In her recent post, The Revolution Will Not Be Funded, @gvgktang argued that “funders and middleman nonprofit organizations dip into resources best allocated directly to local community leaders and their constituents.” In other words, rather than giving to nonprofits to perform public history and contributing to, what increasingly seems to me, a defunct capitalist model, the money should be given directly to local communities to interpret their histories. This would also resolve hegemonic tendencies among public historians, moving them from focusing too much on their own authority towards, instead, supporting their concept of “shared authority.” Emphasizing the authority at the grass-roots level and having them petition input from public historians as they see fit turns the traditional model of public history on its head. Most importantly, moving the money directly to communities who have the strongest vested interest in the work could empower and elevate the work of poor people of color.

This is all theoretical, I fully admit that, and I heartily welcome your thoughts on this. The bottom line for me, here, is that the current system among nonprofits in Philadelphia’s cultural sector is broken. I personally am fully on board with ideas like those from @gvgktang, and I would love to see ideas like these implemented somehow.

What are your thoughts, dear reader? Do you see any possibilities for reformation in the current system among nonprofits? Do you think I am being too hard on them? What are your thoughts on redistributing nonprofit funding to the stakeholders whose stories should be interpreted by themselves? Do you have any suggestions for solutions that have thus far evaded me? Comment below!

100% of the SBD rewards from this #explore1918 post will support the Philadelphia History initiative @phillyhistory. This crypto-experiment is part of a graduate course at Temple University's Center for Public History and is exploring history and empowering education to endow meaning. To learn more click here.

Sources:

Susan Nelson, Getting Beyond Breaking Even: A Review of Capitalization Needs and Challenges of Philadelphia-Area Arts and Culture Organizations, (Philadelphia: TDC, Inc., 2009).

Susan Nelson and Juliana Koo, Capitalization, Scale, and Investment: Does Growth Equal Gain? A Study of Philadelphia’s Arts and Culture Sector, 2007 to 2011, (Philadelphia: TDC, Inc., 2014).

Robin Pogrebin, "Politically Outspoken Director of Queens Museum Steps Down," The New York Times, January 26, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/01/26/arts/design/queens-museum-director-laura-raicovich.html. (Accessed 2/8/18).

GVGK Tang, The Revolution Will Not Be Funded, 2018. https://steemit.com/history/@gvgktang/the-revolution-will-not-be-funded. (Accessed 2/8/18).

"If you can identify your problems but do nothing to rectify them, you didn’t want your nonprofit to survive."

Well said! I think this analogy can be applied pretty broadly. Lots of people out here talking a good game about any number of things that they don't lift a finger to support or change. Not good enough. It isn't going to fix itself.

Well, I think maybe there's something else in play here, an acceptance that the situation may, in fact, be dismal with no way out. No money. No big new ideas. Same old leadership. I've seen that kind of thinking embedded in the culture of cultural institutions going back decades.

Once upon a time, I even heard that one board leader said that if they couldn't afford a 1st class solution, well, then, they'd just have to go with a 2nd class solution... But that board member would say that being 2nd class (or maybe even 3rd) was better than going under. That being institutionally comatose was, in fact, an option. And I think we can find examples of this in our community.

I see what you're saying (and I can think of a couple of examples!) Do you think it would it be fairer to characterize inertia like this as a choice that (directly or indirectly) positions board/staff member wishes not to try to shake things up ahead of the needs or priorities of the constituency the nonprofit is intended to serve? Would that be too reductive?

I think that's very fair to say. You might even go so far as to suggest that the very institutions created to address problems sometimes spend time and money in self preservation. And boards justify that action as "fiduciary responsibility."

But other times that isn't the case and the nonprofit system works like a charm.

What the difference between the two? The right amount of vision, leadership, capacity and - most important of all - the right amount of money.

On the subject of inertia, I think this is also a point where we can elaborate further on what we briefly touched on in class - that in the life cycle of a non-profit there is also a time where it is appropriate to pull the metaphorical plug. My mentality is that after spinning your wheels for so long, when do you make that choice to pull out, and what choices do you make before hand?

I think one option to consider, if the non-profit wants to continue on in a way similar to their original model, is to consider fusing with another non-profit whose mission and constituency is akin to their own. We discussed in class how there are so so many nonprofits in Philadelphia's cultural sector. If there are two with similar missions and constituencies, and they're struggling, why not consider joining forces and growing together instead of dwindling away independently? I'd be interested in your thoughts on this.

Only if the merged, weak institutions can offer mission and programs that make a compelling case for new and greater support. Rather than two weak and similar institutions joining up hoping to maybe thrive, better results might be had by aligning or merging with a stronger partner from a related field with some overlapping characteristics in mission and program. But we should talk about the risks in that scenario, too.

Some excellent processing of the TDC reports and recent issues in leadership, @dduquette! At first, I thought you were headed to propose an overhaul of the board "system" - initiating of a board reform movement, if such a thing is possible. But you are thinking about working in newer spaces (so far as public history is concerned). Very interesting.

But can you or anyone suggest what would that actually look like? Are there any examples out there to cite - or imagine - and possibly make happen?

nice idea, but how could this be done with any effectiveness and who would implement it and would they be compensated? would we simply end up with another organization that while is different than the one it replaces, is not any more effective?

Exactly right! As a result of the constant interest in new ideas and programs to implement the latest interests (and passions!) more and more new nonprofit organizations have been created. Is that an effective solution? If not, what is?