The Harmonic Series [SPECIAL EDITION]: What Does it Mean to be "In Tune"? An Extensive Discussion on Music Theory With @andybets

Welcome to a very special edition of The Harmonic Series! Today, I had intended to post another album review. I had even done the note-taking and outline.

And then I read a comment @andybets left on my review on Brendan Byrnes' Neutral Paradise.

In a light discussion of what functions well as music to work to, Andy posted the following:

"Yeah, I'm ok at ignoring lyrics, but I either need to know the music very well (something I'm not sure my mind is capable of with this microtonal stuff), or it has to be predictable."

What ensued from this was @andybets asking some very good questions, and me attempting to thoroughly answer them and outline some fairly esoteric theory in accessible terms. In fact, his questions were so good, and I was so satisfied with my ability to answer them, that I've decided to make todays post a reproduction of this discussion, in the hopes that you - the reader - can hopefully get something in terms of knowledge or new perspective on music from it:

@fungusmonk:

The need for predictability I get. When you say you're not sure your mind is capable of knowing it, do you mean you don't think you can wrap your head around it or something else? If that's the case, you're a good musician, you definitely can. Something else to keep in mind is that microtonality actually exists in a lot of music already, whether naturally in things like choral music, or in the inflections of style, such as in blues. The thirds sung in traditional blues aren't in tune with equal temperament; they're sung the way they are deliberately, but the musicians likely didn't think of it as microtonal or extra flattened so much as "the way I sing."

@andybets:

I understand what you're getting at, and maybe the models most people use to describe tonal music (if that's the correct name for 'normal' music ;) ) are incomplete.Perhaps I could learn it with a lot of exposure, but I think maybe after years of listening to tonal music, you develop mind/brain structures that are well suited to storing and operating on it, and it would take quite a lot of adaptation. Probably a similar principle to how if you learn a foreign spoken language when you're young, it's more 'natural' to you.I know we 'slur' notes etc. and how important that is, but can you sing a repeatable microtonal scale? I'm pretty sure I couldn't.

@fungusmonk:

The thing with "microtonality" is, it doesn't relate to "tonality" in the same way as "atonal" (no distinct key center) or "polytonal" (simultaneous multiple key centers) which refer to gravity between chords and harmonies and "key."

I don't think it takes as much adaption as you may imagine, rather just beginning to approach it through the familiar principles of tonal music. A term that gets thrown around a lot in microtonal music is "new consonance," meaning intervals not found in traditional tonality, but pleasing to the ear nonetheless. In microtonal music we can still have 3rd's and 6th's and 7th's, but now we have more options, like the neutral 3rd - a pitch equally between the minor and major 3rd.

The fact is, the equal temperament system is a compromise against the natural harmonic series. Its existence owes to the desire of composers to have access to all 12 keys equally in tune, with the advent of keyboard instruments. This means that, scientifically speaking, equal temperament is actually *always* out of tune. If we wanted to play in just one key with perfect tuning, Just Intonation (which derives its intervals from the harmonic series, and is more often than not considered "microtonal") is actually much more "in tune."

The greatest example of this is the tritone. In western music it's considered very dissonant, owing to being out of tune with the harmonic series, but in many eastern traditions and in Just Intonation, the tritone is *exceptionally* consonant, being an equal division of the octave in 2 halves. A perfectly tuned tritone in this regard has no "subharmonic beating" (the sound you hear when tuning a guitar string to the adjacent string is the most obvious example of this).

This comment sort of got away from me because this topic has a lot of depth, but basically I like Byrnes' music a lot because it tends to be fairly close to recognizable tunings and serves as an easy gateway into more esoteric sounds. Here's a video of Byrnes himself explaining his 22-EDO guitar and playing some music on it:

As for your question about singing microtonal scales, yes it's undoubtedly quite difficult in the abstract, but singing at its root is most about blending. Byrnes has been quoted talking about the tracks in which he sings and how it's more about intuitively feeling how your voice sits into the harmonies you're singing over. I'd definitely encourage you to also check out at least some of this choral Requiem by composer Toby Twining. It's in what's know as "zero-limit" Just Intonation, and is entirely a capella. It's likely the most difficult piece of choral music ever performed as it also makes heavy use of extended vocal techniques, but chiefly it's an incredible testament to the deeply human and natural sound of harmonic series based tuning. Here's the Kyrie:

@andybets:

Thanks. It is really fascinating, and I know so little music theory, that it's hard for me to even discuss. People frequently ask what chord I'm playing in a song, and I'll have no idea, because I choose based on whether or not I like the sound, and often through fortunate mistakes! I get the feeling some people with a moderate understanding of music theory can feel limited by it - perhaps not for those with deeper knowledge though, or musicians who are more self-assured and open-minded.I consider myself lucky to be able to create music that I quite like, even though I've no idea what I'm doing as expressed in another language. I think music is probably more fundamental than any modern 'natural language' we use to discuss and analyse it.Do most of us actually prefer things to be slightly 'out of tune'? Could it be that tonal music theory is a bit like classical mechanics, and microtonal (or 'scientific') theory more analogous to quantum mechanics? Do both views perhaps have merits, but neither all the answers? Just throwing around ideas here really with very little knowledge.I will listen to those videos more, they do both seem almost 'normal', and certainly very clever. I hope you find time to record another of your acoustic compositions soon too!

@fungusmonk:

You're asking/raising very good questions/points, so I'm gonna try to break some of this down in depth:

I get the feeling some people with a moderate understanding of music theory can feel limited by it - perhaps not for those with deeper knowledge though, or musicians who are more self-assured and open-minded

This is a very spot on assessment. I'm an intuitive musician too, and people can often mistake my fascination with music theory as cold or academic, but it's ultimately a tool in service of further understanding and mastering tools of expression. A lot of people learn up to functional harmony (chord progressions) and think that it's reductive, but that's only their own failure of imagination and lack of further education, whether by teaching or by independent theorizing. "Music theory" is also a lot more than what most people conceptualize it as, it's any functional or structural explanation of music and why or how it works the way it does.

I consider myself lucky to be able to create music that I quite like, even though I've no idea what I'm doing as expressed in another language

I was raised listening to some quite intricate music, jazz, Brazilian, classical, etc. so for me, it took a long time and a lot of learning to finally feel like I was expressing even a fraction of what was inside me. I wouldn't have reached that nearly as soon - if ever - were I just working entirely in the dark. I say use every tool you can get your hands on in service of developing your ability to speak. Music is like language, and you can express yourself better when you have better words. But a lot of great musicians did just put in so much time simply playing that they developed new things that there were no words for, a great example being in the jazz tradition. It's fantastic that you've developed expression you're happy with without theory, most people don't get that far; don't artificially limit yourself though, and don't make the mistake of thinking theory can't improve your art. I'm always a little ahead of what I know theoretically in my writing, but without learning and understanding what I'm doing and why it works, I'd definitely stagnate and not progress past it

Do most of us actually prefer things to be slightly 'out of tune'?

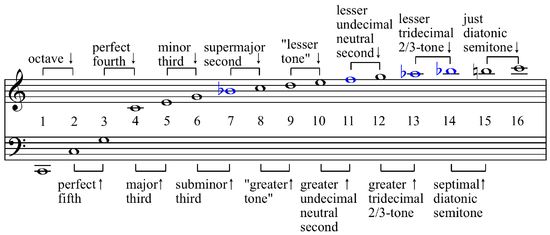

That question is difficult to answer because defining "in tune" gets very slippery very quickly: in tune with what? This can only be assessed in terms of what the person creating the music intends. When it comes to being in tune with the harmonic series, objectively our ears and minds prefer these intervals, as they are present in the overtones of every individual note. Take a look at the harmonic series as notated (and don't focus on the names, they don't refer to the intervals as relating to the first note in the scale, which is what I'll be referring to):

The harmonic series is what the scales of tonal harmony come from, as you can see the octave, perfect 5th, Major 3rd, etc. in its structure. Something interesting and fairly simple that can be derived from this is that the Lydian mode (major with a raised 4th scale degree/tritone, or the note between Fa and Sol, Fi) is actually a closer approximation of the harmonic series than the major scale we all know. This is because that note labelled "11" - called the 11th "partial" (an overtone which conforms to the harmonic series) - appears far sooner in the series than anything resembling the perfect fourth used in major (Fa).

Could it be that tonal music theory is a bit like classical mechanics, and microtonal (or 'scientific') theory more analogous to quantum mechanics?

They're both scientific as all theory is, it's just the science of different function. I would say that analogy seems to deal more with different levels of scale, whereas microtonal vs tonal might be more accurately described in a quantitative/qualitative difference of how we're interpreting information of the same scale, in the form of how we divide the frequency spectrum, most typically within an octave (which is, scientifically speaking, the space between a frequency and another frequency twice as high: A440 vs A880 for example. In the equal temperament of tonal music, the octave is divided into 12 equally spaced tones that make up the chromatic scale.)

This isn't strictly true, because "tonal" also refers to the systems of progression (between tonic (Do) and dominant (Sol)) that emerged from the 12-tone system. Microtonal music can often approximate the relationships of tonal harmony, which is why Byrnes is such a fantastic introduction; take Fluorescent City for example, which is in 22-EDO (equal divisions of the octave):

The progression here is pretty clearly "i, III6/4, III, iv" (as implied by the bass line and the synth melody), and in the chorus, the phrase even ends on a V chord.

Note that Just Intonation is only considered microtonal because of deviation from equal temperament. It actually enables more mathematically consonant sounds, provided you only play in one major key, or a mode of that key; to many, it isn't "properly" microtonal, like other octave division systems or the mind boggling field of non-octave scales (which... let's not go there hahaha).

Do both views perhaps have merits, but neither all the answers?

As far as the merits of each, this all comes back to all theory being ultimately a tool for expression. I find "the answers" most satisfyingly in the genre of Spectralism. In short, Spectralism is a contemporary composition movement beginning in the latter half of the 20th century that considered music not from the perspective of notes on a page - ultimately an abstraction and reduction of what actually happens when hearing music - but as the actual frequency content that the listener hears. This established the idea that all the sounds an instrument can possibly make are valid in composition, from the clicking of the keys on a saxophone, to the hiss of a bow against muted strings. Spectralism makes no rules *dis*allowing tonality, so I ultimately see it as encompassing and validating all possible styles of music.

Another analogy - less complete, but perhaps more accessible - that simply deals with microtonality vs traditional tonality is this: consider the color spectrum, also a set of frequencies:

Red, Orange, Yellow, Green, Blue, Indigo, Violet

consider a major scale:

Do, Re, Mi, Fa, Sol, La, Ti, (Do)

We divide each into 7, but wouldn't it be kind of limiting for artists to be restricted to those 7 colors and none of the nuanced variations in between? Certainly just using those colors is fine if it makes you happy, but so many of the greatest works of history would be impossible without rich nuances and subtle variations in color. In the same way (and this is basically the conclusion here), the theory of microtonal music can be thought of as an expansion of color palette, or construction of new palettes. And just as some colors can be considered to clash with each other, some combinations of tones can be considered dissonant. Of course, these things can only be assessed in relation to artistic intent. Certainly some of the chord changes and non-resolutions of contemporary popular music would make someone like Bach grimace with dissatisfaction, but obviously these two types of music have very different aims in terms of expression. It's up for debate why we will - as a society - accept this readily in art, where in music we cling to what we know so desperately, but regardless: microtonality is just another tool in the box of musical expression options, and it's one with vastly unrecognized possibility and utility - *if* we can just put aside that t doesn't sound like What We Know, and take it for what it *is*.

Thanks so much for engaging me about this, I haven't gotten a chance to articulate any of these things in depth before. Your questions are great and your curiosity is highly appreciated. As you can tell, I *love* sharing my knowledge of music theory, so I hope this is as interesting to you to learn about as it is to me to discuss!

And I'm going to try to record another song for the open mic right now I think...

-

Thanks for reading!

This is an atypical post, but I thought it was very worth sharing. If you ever want to discuss music theory or any of the music I post, don't be afraid to give me a shout in the comments! I'm passionate about all aspects of music, and I love hearing perspectives from others on the topic, as well as sharing my own.

Until next time, keep listening.

Wow! Nice discussion! Very interesting!!!

Glad you liked it!