Netflixing: Metropolis (1927)

If there's one thing about film school geeks that is absolutely insufferable, it is the way they idolize German films of the silent movie era.

Film scholars never waste an opportunity to just gush about how brilliantly made these films are. Their ravings cross the line from obsession into an outright fetishizing of the genre. And the rest of us, if we are polite, have little choice but to let them talk our ears off about their lust for die Stummfilmzeit.

It's frickin' annoying.

It Gets Worse

But the worst part of this whole arrangement---the thing that galls me to the core---is the fact that they're completely right: if you actually take the time to watch German films from the silent era, then you quickly discover that they are fantastic. They are gushworthy. And they do possess a certain quality that many films of the modern era are lacking and sorely need.

There are many explanations for this, of course: for one, silent movies of all nationalities benefit from the fact that there are long stretches without dialogue. Certain emotions---dread, hope, longing, loss---are bred better through lack of human speech than through any kind of declaration on the part of the actors.

But even more than this, there is the fact that, for Germany, the silent movie era occurred around the same time that German Expressionism was exploding as an artistic philosophy. And this, I believe, is the "secret sauce" that makes German silent films so exceptional, because German Expressionism had much the same effect on all forms of art produced in that time and place.

Now, I'm putting my biases on display here, since I hold Expressionism in higher regard than other artistic philosophies (much more than that French Existentialism crap). But I don't think it's incorrect to say that Expressionism is the perfect mate for motion pictures. These two powers blend beautifully, and not enough movies take advantage of this tool.

So you'll have to forgive me, because I'm going to talk your ear off about Metropolis.

The First Sci-Fi Film?

Regular readers of my blog will remember this post about iconography. The more I study it, the more I am convinced that Expressionism is the key to that, as well.

First released in 1927, Metropolis is considered by some to be the first science fiction film, even though this is provably false. George Melies, who directed over 500 films from the 1890s to the 1910s, made many science fiction pieces. Furthermore, Thomas Edison himself strayed into the genre at least once, when he produced a short film adaptation of Mary Shelley's Frankenstein.

That said, Metropolis may be the first science fiction film that was tooled as a blockbuster. Unlike the previously mentioned sci-fi films, Metropolis is feature length, and it did things with special effects that George Melies and Thomas Edison could only dream of, including the flooding of an entire movie set.

The production cost 5 million Reichsmarks (which probably was not a lot of money, considering that the film was made during the Weimar Republic era, when hyperinflation was rampant in Germany), and the filmmakers were apparently driven by the desire to make this production as big and flashy as possible.

They succeeded.

The Story

In the year 2026, society is divided into two classes: the privileged, who live in the glorious and futuristic city of Metropolis, and the workers, who live in the undercity among the machines that power and facilitate the wonders of the upper world.

The workers are miserable, because they have to...flip switches and push buttons all day.

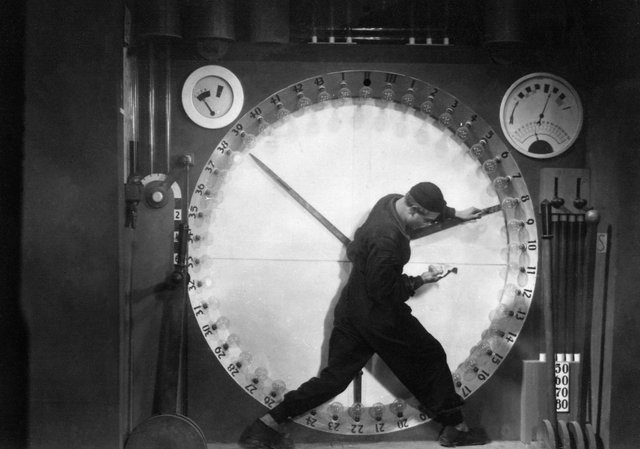

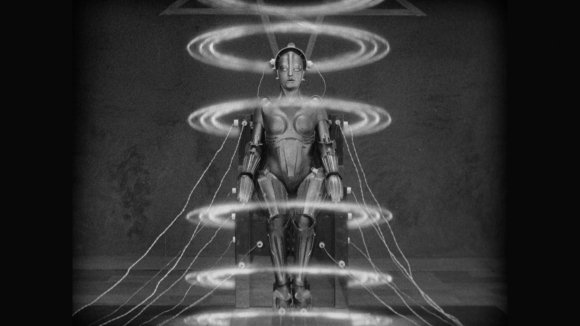

Yet another iconic image from the film.

And, apparently, flipping switches and pushing buttons is the hardest job in the world, because the workers hate doing it and are so exhausted by the effort that they sometimes collapse on the spot from fatigue.

(This is one little nitpick in an otherwise excellent film. One other nitpick would be the fact that the priviliged people seem to outnumber the workers by a huge amount, as the upper city of Metropolis is much bigger than the undercity and has thousands of cars and airplanes constantly moving people through it. Honestly, what society has ever said, "We have no problem oppressing the bottom rung, but only if that rung is smaller than all the others?")

And the plight of the workers is troubling to young Freder Fredersen (the guy so nice they named him twice). As the son of the cold and uncaring tycoon who rules Metropolis, Freder is privileged even among the privileged and spends most of his time in the Eternal Gardens---a romping ground for the sons of the ultra wealthy.

But all that changes when Freder catches a glimpse of the angel-faced Maria...

...whom he follows into the undercity in hopes of wooing her. There, for the first time, he sees the plight of the workers and is utterly horrified to see that this is how real people live (there does seem to be a parallel here with the story of Gautama Siddhartha).

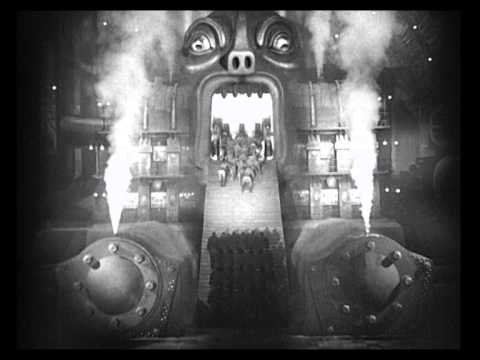

He is so frightened by the machinery and the squalor, in fact, that he has a vision of the heathen god Moloch, depicted as a giant machine that eats the underground laborers.

"I am Oz, the great and powerful."

Upon discovering that his father is aware of the awful working conditions and will do nothing about them, Freder decides to run away. He abandons his station and becomes one of the workers, experiencing their toil, but also getting another opportunity to see Maria.

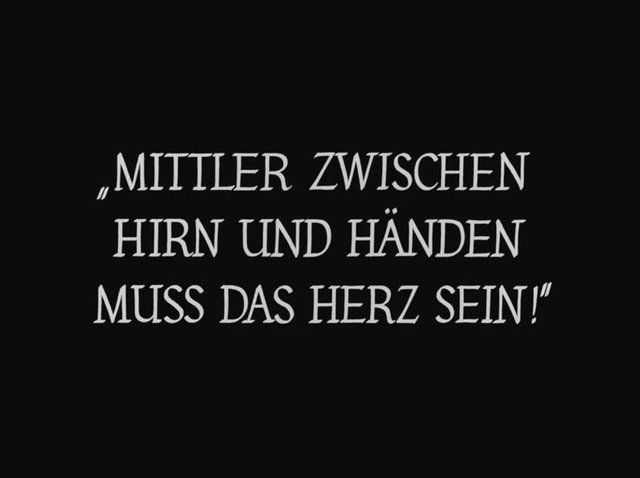

Maria, it turns out, is something of a prophetess who spiritually guides the workers and holds masses in the 2000-year-old catacombs beneath the undercity, where she predicts that a mediator will come to bring together the head of Metropolis (the city's rulers) and the hands of the city (the workers). She calls this mediator "the Heart", and advises the impatient masses to await his coming, instead of violently rising up.

Freder comes to realize that he is the only one who fits this description, and plots with Maria to peaceably bring about reform to Metropolis, while the two fall instantly in love.

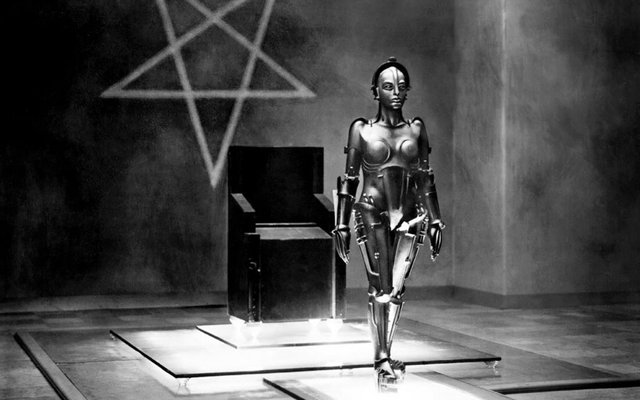

But Freder's father has other plans. Upon learning of Maria's following, he enlists the help of his old friend and romantic rival, Dr. Rotwang. Rotwang is still bitter about losing the love of his life to Mr. Fredersen, only to have her die in childbirth. And he copes with this by building a "Machine-Man" to replace her.

This film may have pioneered the use of "glowing rings that slide up and down" as a method of magical transformation.

The robotic "Hel" can assume human form, and Mr. Fredersen commands the doctor to give her the form of Maria, so she can commit evil acts while posing as the prophetess (this might be the first time the "evil twin" trope was ever used).

Hel, disguised as Maria, literally becomes the whore of Babylon, and induces the young men in the Eternal Gardens to fight and even kill each other for her attentions, performing an on-screen dance that would be considered risque and burlesque even by the standards of today.

Then, in the catacombs, she tells the workers that she, Maria, has reversed her policy of nonviolence, and now wants to foment an all-out rebellion, with every man and woman of the workers participating.

But this is all part of Mr. Fredersen's plans. For once the workers resort to violence, he will be justified in using violence against them, allowing him to permanently put an end to their aspirations.

Except that Dr. Rotwang has programmed Hel to betray Mr. Fredersen at the last moment, and engineer the death of both him and his son.

The clock is ticking as Freder, Maria, and a small group of allies work to stop the rebellion and save Metropolis.

The Message

At first glance, Metropolis seems like a typical, dime-a-dozen dystopia story, where a heartless ruling class oppresses the saintly peasants.

But that's not where the story ends up.

Metropolis even heaps a bit of praise on the idea of the privileged caste, remarking that the futuristic wonders of this city would be impossible without the ingenuity and vision of these elites. Furthermore, it depicts the uprising of the workers against the privileged as a bad idea with disastrous consequences.

Message fiction is almost never any good, and there can be no denying that Metropolis is message fiction. The story believes so much in its own moral that it actually takes the trouble of printing it onto the screen in large letters, at both the beginning and the end of the film.

"The mediator between Head and Hands must be the Heart," it proclaims.

But I have to admit that the movie thrives despite its blunt moralizing, though this is only possible because the film is honest enough to show the flaws on both sides of the issue, all while avoiding any self-righteousness and passing no judgment.

Above all, the film decries the use of violence and fanaticism in the pursuit of one's political agenda, a lesson we might all do well to keep in mind no matter the place or time we live in.

Netflix's Version of the Film

Metropolis premiered in an age of rampant censorship. As such, many different cuts of the movie exist, and a number of the film's segments have never been found.

However, a few of the lost scenes were discovered in Argentina only a few years ago. The quality of the Argentinian prints, however, leaves a lot to be desired. The images are scratchy, and were resized for the Argentinian projectors, effectively giving them a different aspect ratio. Nevertheless, these segments have been included in the latest release of the film, which happens to be the version found on Netflix.

The original soundtrack has been faithfully recreated with a full orchestra and modern recording equipment. Past releases of the film have used a number of different soundtracks, including one from the 80s where rock icons of the day created their own score for the film. If that's your preferred version of the film, you may be disappointed by what you find here.

My Judgment

Metropolis is two and a half hours long. I was originally planning to watch it in installments, but once I got it started, it was surprisingly hard to stop. I ended up watching the whole thing in one sitting, and I'm glad I did.

I know it makes me sound like a film snob, but modern movies could learn a lot by watching this. And some movies have, since so many filmmakers have been influenced by this work. Reworkings and adaptations of the piece have been made time and again. There was even a popular manga based on the film, which was then adapted into an anime movie.

There are some movies you should watch only because they are so culturally significant. Metropolis is not one of those. Rather, it is a movie you should watch because it is genuinely entertaining and stirs real emotions in the viewer. The fact that is is culturally significant is just a byproduct of how good a film it is.

And it is on Netflix right now, so you need not wait to watch it.

Image Citations

- Nosfera-who? Source: Nosferatu

- The Scream Source: Edvard Munch

- Hel hath no fury. Source: Metropolis

- On the clock. Source: Metropolis

- Santa Maria. Source: Metropolis

- Pass through the fire. Source: Metropolis

- The road to Hel. Source: Metropolis

- The mediator. Source: Metropolis

- The moral. Source: Metropolis

Previous entries in the Netflixing series:

Past Years

TV Shows

Movies

I was a little concerned by how this started..:)

Cause yes, those movies are great. I really like Nosferatu.

Yes, German silent films are fantastic, but I have to admit it gets on my nerves that so many film buffs CAN'T. STOP. SLOBBERING. OVER. THEM.

If I wasn't already familiar with the quality of German silent films, I would probably go out of my way to avoid them, just to spite all the rabid devotees out there.