Mars Desert Research Station: My Mission to (Simulated) Mars

Mars Desert Research Station is a replica Mars habitat operated on the San Rafael swell of the Utah Desert just outside of Hanksville, by the Mars Society. It's a nonprofit organization the purpose of which is to do everything possible to promote and advance the cause of colonizing Mars, and to carry out various exercises which yield data that will be useful to the astronauts who someday travel to the red planet.

Pardon the censored faces. I write a lot about psychedelics on this blog and don't know whether anyone else on my crew would want to be associated with such a page, however remotely. Better to assume they don't than the inverse, besides which it would also be foolish for legal reasons to post my photo on this account, and it's generally a bad idea to broadcast any identifiable details about you to an anonymous internet audience.

Though of course it's not on Mars, for any of the resulting data concerning methodologies astronauts should use (for example) to retrieve injured crew members and get them through the airlock without exacerbating their injury, strict protocol must be adhered to. For every minute of every day we were there, each of us had to pretend we actually were on Mars.

This included never going outside except with a sim suit on (which circulates fresh air into the helmet with a battery powered fan, simulating time-limited life support) and cycling for five minutes through the airlock any time we wanted to enter or exit.

The burdensome nature of it really impressed upon me that while the novelty of living on another planet would be magical for a few days, having to do these things every day for the rest of my life would be unbearable.

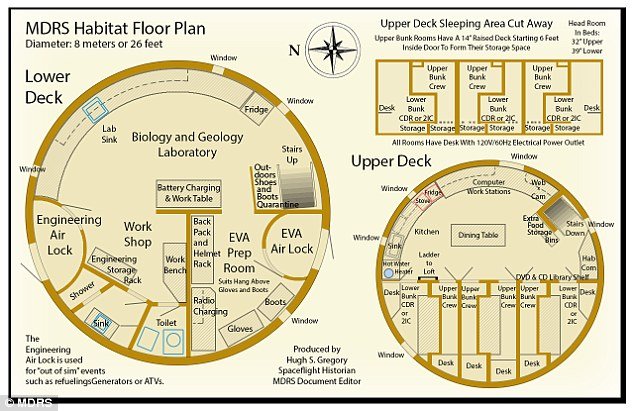

The habitat was designed according to the real payload capacity that future heavy lift, Mars capable rockets will have. The living space is modest but I wouldn't call it cramped. Just exactly enough that we didn't trip over each other or feel packed in like sardines.

The habitat recycles water using a grey water system, filtering it through plants in an adjacent "green hab" module. Some power came from solar, weather permitting, but most came from a huge diesel generator meant as a stand-in for a nuclear reactor.

Accommodations were cleverly designed to make maximum use of space such that we were technically sleeping above and below one another, like bunk beds, but in separated spaces. The overhang in the photo is where my "neighbor's" bunk is in the next room over. Intelligent use of space really made living in such confined quraters much more tolerable than it would have been otherwise.

Meals, breakfast included, consisted of dehydrated stuff. Often from big airtight cans of dehydrated vegetables. We'd take a survey after every meal to vote on which of the dehydrated meals was least awful, pursuant to devising a practical but also pleasant diet for 'Marsonauts'. Then came morning yoga. Satan has another name, friends, and it is "compulsory morning yoga". That is when I least want to exercise.

Then we began repairs. The last crew left a lot for us to fix. Stuff wears down fast out in the desert, and very basic, crucial stuff needed our attention. MDRS operates on a shoestring budget, what maintenance it receives is mostly done by volunteers.

Then came morning EVA. Taking rock samples for study back at the hab, as this desert was chosen (along with the other MDRS simulation sites) because it is geologically similar to Mars. We traveled on some days by gas powered ATV. Battery powered would've been more authentic, but that's outside the MDRS budget.

I felt outclassed by my fellow crew members from day one. A NASA biologist, an astronomer, a paramedic, a professional photographer...then me, a guy who dives a lot and writes about it. My principle purpose on the mission was to write a report on sea/space analog principles and how underwater exercises can prepare astronauts for Mars surface operations.

It was very well received though. "This is exactly what we want to see more of from all of you" the reply read. I kind of shrunk into my seat at that part since writing a report is really a minimal contribution compared to everybody elses hard work.

I also assisted the biologist with experiments involving the use of chlorella and spirulina algae as a bioregenerative CO2 scrubber, oxygen source, water purifier and supplemental source of nourishment. They are in fact nutritionally complete(!) save for vitamin B. You could survive quite a long time on algae alone, it just wouldn't be terribly pleasant.

I had occasion to visit the nearby observatory with the astronomer of the crew. Like the hab, it was paid for in large part by the Musk Charitable Foundation. Yes, that Musk. MDRS has some impressive, encouraging connections.

Later, the two of us assembled the teleoperated rover, donated by Georgia Tech. Naturally I fucked up part of the assembly process but my fellow crew member was perfectly gracious about it. As ever, I felt like an amatuer surrounded by seasoned professionals.

The rover allowed us to carry out various simple tasks like exterior hab inspection, and generator inspection without having to go through the tedious process of suiting up and cycling through the airlock. Proposals to use a flying drone for this have garnered interest, though on Mars it would need some huge props indeed in order to get airborn in the whisper thin atmosphere.

I was the only one there who wasn't gung ho about living on Mars. I participated mainly to learn, and to contribute in some small way to an endeavor that is crucial to the future of humanity.

If you've read any significant number of my articles, you'll know I want to live underwater, not on Mars. If that's difficult to understand, look at these photos and ask yourself if you'd like to live in the Utah desert for the rest of your life.

That's what Mars is. The Utah desert, only colder, with a thinner atmosphere, more radiation and so on. I do not regard it as a marvelous, romantic adventure but a grim necessity if there are still going to be humans around in a thousand years to have discussions about it.

The existential threat to our species is real. Remember the Chelyabinsk meteor back in 2013? It rattled people because we normally don't see meteors that close to population centers. Earth gets hit all the time, in fact.

Usually they blow up higher in the atmosphere and away from cities, so nobody is ever aware of it. Earth has even been slammed by some meteorites of devastating size. There are impact craters all around the world you can visit.

It is really difficult to communicate to the public what a serious threat this is. Our lifespans are very short compared to the timescales relevant to major impacts, so superficially it seems like some far fetched thing that could never happen due to its rarity in the experience of the average person. But it's happened before, and nothing prevents it from happening again, even wiping out humanity altogether.

Unless we had decades of advance warning, there's very little we could do about it except to have a backup of human civilization on a different planet. Our long term survival odds jump dramatically with even just two populated worlds.

Deep time is unfathomable to most people, concerned principally with small, near term issues relating to their own day to day lives. But we must grasp deep time, geological time, in order to see how frequent major impacts really are and how easily we could go extinct within the next few centuries if nothing is done to insure against it.

There exist issues with terraforming, but not the ones most think. The lack of a magnetosphere is actually no problem for example, because the rate at which an artificially generated atmosphere would be stripped away by solar wind is so incredibly slow (millions of years) as to be irrelevant to us, and the same machinery used to generate the atmosphere could be used thereafter to maintain it.

My perspective, then, is not "we should go to Mars because it's an adventure". Not because it's cool or exciting, the reason which stirs the heart of most space enthusiasts. The big picture view of human survival vindicates the practical necessity of establishing a backup of humanity somewhere other than Earth. Failure to do so will guarantee extinction, it's just a question of when.

Very interesting! I actually thought the fact that Mars doesn't have a magnetic field was a serious issue with the idea of terraforming the planet. I find it interesting that it would take millions of years for solar winds to strip the atmosphere away. I guess Venus doesn't have an internal magnetic filed and it is closer to the sun and has a crazy thick atmosphere. I guess my big thing is still the amount of energy required to terraform and entire planet would be incredible.

must be real fun to do a simulation like that

For two weeks, sure. But actually living out the rest of my life on Mars would be a very different story.

I would need the outlook of a way to build up bigger housing, or putting work into improving living conditions to keep my morale up.

Just keeping to repairing things and collecting data would drive me mad.

I agree with your conclusions. Exploration is important. This is how we learn new things. But exploration may also mean we will not find anything. There is always a risk...

Thanks for sharing these pictures and story!

hi,

I wrote a cute little story about a baby dolphin and all the posts he read on steemit last week and your post is in it!

have a look, I hope you like it

thanks

This post has been linked to from another place on Steem.

Learn more about linkback bot v0.3

Upvote if you want the bot to continue posting linkbacks for your posts. Flag if otherwise. Built by @ontofractal