Badass Women of History--Christine Otis Baker

Here's a lady you probably haven't heard of unless you're REALLY into early colonial American history. She's well worth getting to know.

Who Was Christine Otis Baker?

She was born March 15, 1689, the daughter of Richard Otis and his third wife, Grizel Warren. Both Richard and Grizel were second generation Americans, with their parents immigrating directly from England in the early 1600's. They were also among the first English inhabitants of the town of Dover, New Hampshire.

Back in these early days of English colonization of North America, relations between the English and the Natives were not always friendly. The settlers and the different tribes in the area went through periods of cooperation and war. It all really depended on who was in charge of each group at the time, and their policies toward the other group.

It just so happened that Christine was born during a time when war was on the horizon, thanks to hard-line policies against each other by both the de facto mayor of Dover, and the leader of the local Native tribe. The previous leaders had established a friendly environment of community cooperation that neither of the new leaders wished to continue.

This political atmosphere would shape much of Christine's first three decades of life.

To Understand What Happened to Christine, You Have to Understand the Politics of Early Dover

Again, unless you are into colonial American history, or the history of Native conflicts with English settlers, you may not have heard of her. But, in New England, she is still remembered, and quite famous among those who have long family histories there.

Her story is an interesting one.

It all begins with the politics of relations between the Native Penacook tribe and the first Dover settlers.

At the time of Christine's birth, a 50 year peace had existed between the first English settlers of Dover and the local Penacook tribe. Passaconaway was the local Penacook leader when the first English settlers arrived in town, and he instructed all of his people to be gentle with them. The English were kind to the Penacook in return, and Passaconaway's son continued this tradition.

It was only when a new leader of Dover, Richard Waldron, emerged, that things got sticky between Dover and the Penacook. Waldron accepted 200 Native Wompanaug refugees from Massachusetts into town, giving them shelter from the burgeoning King Phillip's War that they did not want to participate in. However, Dover was technically part of the larger colony of Massachusetts at this time, and leaders from Boston demanded any Wompanaug Natives from the area be returned to it.

This put Waldron in a precarious position with the Penacook tribe; even though the refugees weren't Penacooks, they were Penacook allies. Plus, Waldron had just signed a renewed peace treaty with the Penacook, who were now led by Passaconaway's grandson, Kangamagus.

Waldron invited the Wompanaug refugees to play in some "mock" battle games with the Penacook and the English settlers....a common pastime for everyone in Dover at the time. He also invited the Boston militia to come, unbeknownst to the refugees.

19th Century Woodcutting of the "Games" Waldron Arranged

Once the games started, the militia appeared, and separated the refugees from the Penacook. Two hundred Native refugees who had not taken up arms against anyone were marched back to Boston, where some of them were hung, and some were sold into slavery.

Kangamagus felt betrayed by Waldron, even though no harm came to any of the Penacook. He vowed revenge on him.

This is where Christine's story really starts.

What, Exactly, DID Happen to Christine?

Like many of the badass women of history, Christine was famous during her own lifetime. Her legend still continues, especially among longtime New Englanders.

What happened is this:

Because Kangamagus felt so betrayed by Waldron, he decided his whole tribe would take revenge on him. But, it wasn't just Waldron. Most of the town of Dover, with a few notable exceptions who were known to have personal relations with the Penacook, were subject to Kangamagus's plan for revenge.

So, on June 27, 1689, when Christine was just three months old, Kangamagus organized a surprise raid on Dover.

It started with some Native women approaching the home of Christine's father, Richard Otis, and asking for shelter for the night. It was a common request, so no one at the Otis household thought anything of it; the women were let in through the protective wooden gates surrounding the house and its farmland.

19th Century photo of a garrison house like the one Christine was born in and lived in at the time of the Penacook raid on Dover.

After the household went to bed, the women opened the gates from the inside, and let in their warring tribesmen.

19th Century Imagining of the Penacook Raid on Waldron's House

There were other groups of Native women doing this at other houses in Dover at the same time....including Richard Waldron's house. Waldron was badly mutilated before he was killed, and some of the ways the Penacook mutilated him were designed to humiliate him as much as hurt him.

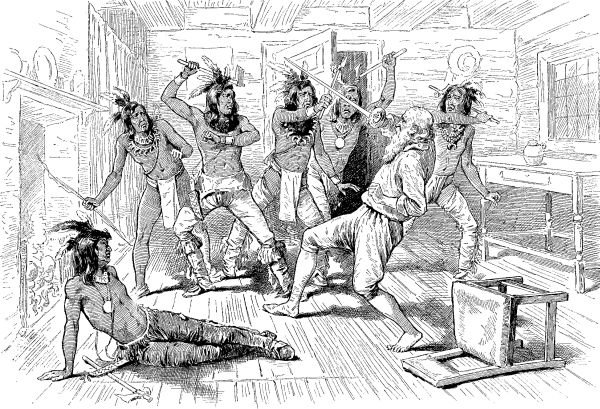

19th Century Imagining of the Fight Between Waldron and the Penacook

Many other families in Dover were raided that evening, usually with members being killed or captured, and houses being burned and looted. A couple of families escaped only because they were out of town at the time, but their houses were ransacked in their absence.

On the night of the raids, Richard Otis was killed, as was his adult son, Stephen. Richard had two children with Grizel, two year old Hannah and three month old Christine, whose birth name was actually Margaret. During the raid, the raiders took little Hannah by the legs and smashed her head against the hearth stones by the fireplace, killing her. They did this because they thought she could not keep up with the party of captives they intended to take with them.

Grizel was actually lucky her infant was permitted to live, as other babies taken as captives in similar raids on other towns were not so lucky, mainly due to the noise they made.

The Otis house was ransacked and burned down. Grizel and the infant Margaret (later to be re-named Christine), Richard Otis's daughter-in-law by his murdered son Stephen, and Stephen's three children were all taken as captives.

The captives were divided into two groups, each taking a different route to Canada, where the Penacook intended to sell them as slaves to the French. All of Richard Otis's captured family was in one group, except his 14 year old granddaughter, Mary. Separated from her mother and two younger brothers, her group was released and returned home a few days later, when a few Dover residents who were on friendly terms with the Penacook went after them and negotiated for their freedom.

The rest of the Otis family went to Canada. None of them ever returned to the English colonies, with one exception....Christine.

Christine's Life in Canada

As an infant who still needed her mother, Christine couldn't return to New England right away. Her mother, Grizel, was purchased by a French settler, a man by the last name of Lagarenne. Christine was part of the purchase package.

Lagarenne soon freed Grizel and married her. There was a condition to this freedom, though....she and her daughter had to become Catholics, like all the French. As New England Puritans, that must have been offputting to Grizel at first, but she had to think of the welfare of her child.

Grizel converted, and was re-baptized with a new name....Marie Magdaleine. Her daughter, Margaret, was re-baptized, too, and given the name Christine, which she used the rest of her life. Once she was old enough to start school, Christine was sent to learn at the local convent, sequestered among the nuns.

She received an exceptional education there, one that far surpassed what most women in New England were getting. But, as she got older, she was also pressured by the nuns and her mother and step-father to become a nun herself. This was something the strong-willed Christine knew she did not want for herself, and she refused to do it.

So, instead of becoming a nun, her mother and step-father arranged for her to be married, once she reached the appropriate age. Catholic girls married much younger, on average, than Puritan New England girls. While Christine had a say on whether or not she became a nun, as no one could force her to take those vows, she could be forced to marry, and she was.

She married Louis LeBeau on June 14, 1707. They had a son and two daughters together. The son died as a baby, but her two daughters with LeBeau lived past childhood.

Christine Meets Her Future Second Husband

Sometime during Christine's seven year marriage to LeBeau, another New England captive was brought into Montreal, where the LeBeau's were living at the time. This young captive was a handsome man named Thomas Baker, a militia captain from Massachusetts. Baker tried to escape, was caught, and set to be shot, when LeBeau paid to ransom him and set him free.

LeBeau's reasons for ransoming Baker are not known, but perhaps it was in sympathy to his wife's New England origins. At any rate, Christine and Thomas met during this time, and formed a friendship. When he left to return to New England after he was ransomed by her husband, he and Christine did not forget each other.

Christine Returns to New England

Louis LeBeau died in 1713, leaving Christine a young, beautiful (by local accounts) 25 year old widow with two living children. In 1714, Thomas Baker returned to Montreal, this time voluntarily, as part of a New England contingent sent by the Puritan government to ransom back captives from there. He and Christine met again, and remembered each other.

Baker must have been a bit smitten with Christine, because he tried to get her ransomed, even though she'd grown up in Montreal, and it was all she knew. And, Christine must have felt something for Baker, because she wanted to go.

French authorities, however, refused to let her go....at first. With some negotiation, Thomas Baker was able to secure her release, but it came with conditions. Those conditions were extremely harsh, and designed to make her agree to stay:

- She could not take any of her personal belongings with her. Only the clothes on her back could go if she decided to leave.

- She could not take her children.

Faced with these conditions to her release, most women would have relented and stayed where they were. Not Christine. She agreed to the terms, and made plans to leave Canada with Thomas Baker.

Even her mother, already adapted and accustomed to French life at that point, tried to dissuade her from going. She famously told Christine that she knew nothing of what life was like in New England, where women were required to make their own butter and bread; such things were readily available for purchase in stores throughout Montreal, and Christine had no training in making them.

Christine still insisted she would go.

And, she did.

Cunning from the beginning, she tried to smuggle her household goods and her daughters out of Montreal on a boat with Baker, but the parish priests discovered them, and took everything, including the girls. That might have deterred another colonial woman from trying again, but not Christine.

Making a second attempt at leaving, only this time with only the clothes on her back and whatever she could carry in her hands, per the terms of her release, Christine arrived back in New England in September of 1714, 26 years after she left it as an infant. She married Thomas Baker in January the next year, and they lived in Brookfield, Massachusetts until 1734. Then, they moved to Dover, the town of her birth, and the scene of her capture by the Penacook.

Christine was truly home at last.

Christine and Her Ongoing Negotiations with the French

Though Christine was back in New England, where she joined a Puritan church with her husband, and was re-baptized (her third baptism in her life) with her original name of Margaret (although she continued to go by Christine), she and the French were not done with each other.

First of all, the French still had her two daughters by Louis LeBeau, and she wanted them back. Second, the French believed she was falling into heresy by converting back to Puritanism, and took an oddly particular interest in bringing her back to Montreal and Catholicism.

Christine received letters from her old parish priest in Montreal for years, cajoling her into coming back and re-joining the church. He made all kinds of theological arguments to get her to agree. She kept showing the letters to her Puritan minister, who provided her with theological arguments of his own that she used to argue with the priest.

Christine returned to Canada in 1718 with the objective of retrieving her daughters. However, the parish priests of Montreal, who had most of the political power, refused to let them go with her. They even refused to let her see them. There was no reunion between mother and daughters, and the girls died a few years later, four years apart from each other, at the ages of 10 and 16, respectively.

It speaks again to Christine's fortitude that she once again left Canada without them, to return to her new/old life in New England.

In 1727, a year after the death of her last Canadian daughter and the same year her son, Otis Baker, was born, Christine received one more letter from her parish priest in Montreal, listing all the reasons she should come back and re-join the church. This time, she asked the governor of Massachusetts to reply for her, which he did. The priest did not write to Christine again.

Conclusion--Christine Becomes a New England Heroine

From the moment she returned to New England shores with Thomas Baker in 1714, the people of New England took a great deal of interest in Christine. They were mesmerized by her tale of captivity, forced marriage, life among the French, and leaving everything she had and everyone she knew to return to the land of her birth with the man she loved.

The town of Deerfield, Massachusetts granted her an expensive lot of prime land upon her arrival, and she and Baker built their house on it soon after their marriage early the next year. When a real estate speculator cheated them out of the full value of the land and house when they sold it to move to Dover in 1734, the people of New England once again came to their hometown heroine's aid by granting her 500 acres of valuable land in Maine.

Christine was able to sell this land easily, and she and Baker used the money to build a new house in Dover, the town of her birth. Baker was a practical invalid at this point, from injuries sustained over his long military career, and Christine turned part of the house into a tavern, which she ran completely on her own.

Unlike most taverns, which had unsavory reputations, Christine's was always held above reproach. The Puritan authorities even approved of it, which was an almost unheard of thing, and the finest, most respected New Englanders made a point to visit it when they were in the vicinity.

Thomas Baker died in 1753, and Christine outlived him by nearly twenty years, dying on February 23, 1773, just prior to the American Revolution. She and Thomas are both buried in Dover in the same plot, their love story and Christine's amazing journey from captivity to home again still captivating native New Englanders three centuries later.

Cemetery in Dover where Christine and Thomas are buried in unmarked graves.

Pre-Revolutionary America doesn't have too many female heroines on record. Christine Otis Baker is one of them, and her story deserves to be remembered.

This post has been linked to from another place on Steem.

Learn more about linkback bot v0.4. Upvote if you want the bot to continue posting linkbacks for your posts. Flag if otherwise.

Built by @ontofractal

Thanks, @linkback-bot-v0. :)

This is a pretty interesting story for me, as a genealogist. Christine is a many times great-aunt of my husband. Richard Otis's granddaughter Mary (daughter of his son, Stephen), was in the group from Dover who were rescued before they got to Canada. Her mother and brothers in Canada sent letters giving up their rights to Richard Otis's property, and Mary and her husband built their house on it, where it stood from 1695 to 1972. Mary is my husband's 9x great-grandmother.

very cool story and even cooler that it has this personal history for you! love that you post about bad ass women :-))

Thanks, @natureofbeing. I'm enjoying writing about them. :)

Thanks, @virtualgrowth. :)

The editing features were wonky tonight. I couldn't get a link to raw HTML or Markdown on this post, so I couldn't make large headers or anything, like I usually do. I hope people still read it.

Actually, never mind on that. I just saw the editing interface has changed slightly, and now I don't need raw HTML to make larger headings, or to insert images. Cool! That will save some time in getting these posts formatted nicely.

Yeah, same here...

Very interesting post! I look forward to more.

up/fol

Thanks, @areynolds!