WHY PEOPLE SHUN WEALTH: The LAW of JANTE

“Human beings hold each other in check by means of terror. We fight to increase dread in others and to mask our own.”–Aksel Sandemose

Picture of Aksel Sandemose Book

Aksel Sandemose (He is Danish but he lived in Norway) #reading

Courtesy Google Images

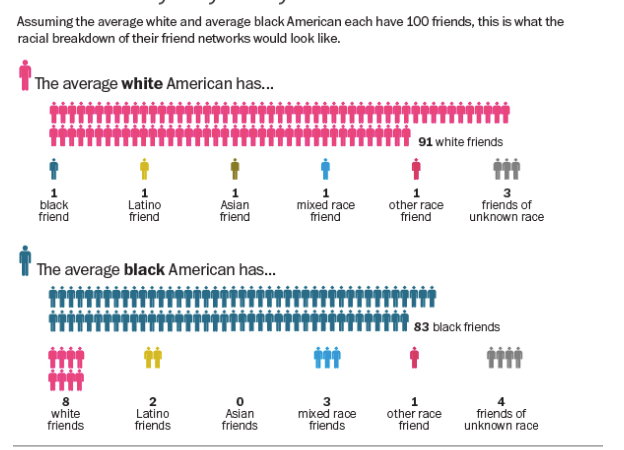

In Minnesota, it’s called “Minnesota Nice”, and it compares as a regional variation of “Tall Poppy Syndrome” . The Scandinavian variation is called JANTE LAW. The book was based on the small town where Sandemose grew up in Norway which he renamed JANTE. Though he was Danish, he wrote books in Norwegian. He wrote: "En flyktning krysser sitt spor," which translates as "A Fugitive Crosses His Tracks." In this town called JANTE, there are a series of rules They are as follows:

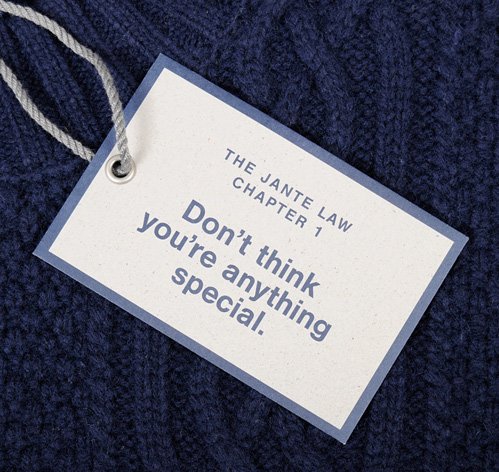

1. Don't think you're anything special.

2. Don't think you're as good as us.

3. Don't think you're smarter than us.

4. Don't convince yourself that you're better than us.

5. Don't think you know more than us.

6. Don't think you are more important than us.

7. Don't think you are good at anything.

8. Don't laugh at us.

9. Don't think anyone cares about you.

10. Don't think you can teach us anything.

And lastly, the final, unspoken law, and it is the enforcement arm for the other laws:

11. Don't think that there aren't a few things we know about you.

Those laws immediately became a sensation throughout Scandinavia, where it was felt they described a social phenomenon that focused on the good of a community over its individual members, at best, and at worst repressed and minimized all achievement by the individual.

The Following is excerpted from A Thesis Presented by KEVIN J. TURAUSKY, Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS February 2011 to Anthropology

“The idea of equality for all is one of the central elements in modern Swedish society and Swedes have traditionally viewed their country as a bastion of tolerance and justice. This self-appraisal and reputation are being challenged in this new globalized world where waves of immigrants are moving into the country.

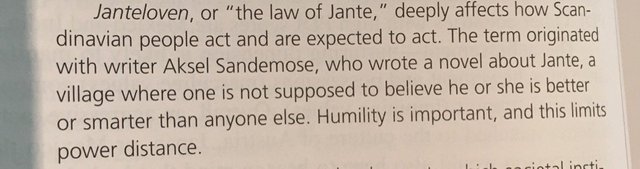

Despite the increase in hostility towards foreigners, Sweden’s progressive stance on social issues stems from a central component of their culture: the Jante Law (pronounced YAN-teh), an unwritten social code governing people’s behavior. #knowledge

Courtesy Google Images

In brief, the Jante Law is a set of social provisions in Swedish society that instruct people to not aggrandize themselves and to distrust those who do. While it is often seen pertaining to materialist acquisition, such as conspicuous consumption, it applies to intellectual ability, physical appearance and general ambition. It is customary to not just downplay one’s strengths in public but also to genuinely believe that one is not particularly special despite whatever traits one might have.

These unwritten social codes inform much of their contemporary society, from everyday behavior to official policy. Because much of Sweden’s emphasis on equality is rooted in the Jante Law’s cultural mores, Bourdieu’s habitus perfectly applies to this adherence to unspoken rules.

Habitus is an “immanent law, lex insita, laid down in each agent by his earliest upbringing, which is the precondition not only for the co-ordination of practices but the practices of co-ordination, since the corrections and adjustments of the agents themselves carry out presuppose their mastery of a common code . . .” (Bourdieu 1977:81).

That is to say habitus is the set of behaviors one follows not because one must but because it would not normally seriously occur to the person to act otherwise. Habitus forms the foundation of one’s personality, as it is the aggregate of one’s habits, beliefs and what one takes for granted. The Jante Law functions internally as well as externally; it is propagated not only through the policing of one’s own behavior but policing the behavior of others.

Because there is no actual law being broken, the only punishment for transgressing the Jante Law must be meted out in the form of disfavor and the loss of social capital. Aksel Sandemose wrote in his 1936 novel, A Fugitive Crosses his Tracks, of the effects of an entire town growing cold and hostile to those who would not obey the Jante Law to the point where living in the town became untenable.

Courtesy Google Images

While the effect of being raised in a society where one is taught not to consider oneself better than anyone else is normally enough to keep people in line, sometimes additional coercion is necessary. This is what Althusser identifies as an Ideological State Apparatus.

Such apparatuses, he notes, function massively and predominantly by ideology, but they also function secondarily by repression, even if ultimately, but only ultimately, this is very attenuated and concealed, even symbolic. (There is no such thing as a purely ideological apparatus.) Thus Schools and Churches use suitable methods of punishment, expulsion, selection, etc., to ‘discipline’ not only their shepherds, but also their flocks. (1971).

These behavioral codes are still learned in schools and churches in Sweden, though the largely secular Swedes are less likely to be directly influenced by the latter. The Jante Law’s incidental presence in the school system allows it to be perpetuated as an ideology in society. Though much less direct nowadays than in Sandemose’s novel, the Jante Law maintains its control over people by making them fear the envy of their peers and neighbors.

Courtesy Google Images

The provoked envy of the community serves as the repressive component to the Jante Law.

Additionally, while Sandemose’s novel takes place in a small town rather than on the state level, the Jante Law can be found throughout Sweden and Scandinavia. The implication seems to be that the fictional town of Jante itself is not the only place the Law exists, but that its particular manifestation of it is more cruel and repressive than in other towns.

Those who transgressed the Jante Law in Jante would likely be able to learn from their mistakes and get along well in another town, but if a person rejected such conformity entirely then they would have very few options available to them. They may feel the need to flee the country entirely, as did the novel’s titular fugitive, Espen Arnakke, or would accept having few friends and alienating coworkers.

Being mindful of where one’s own ideas come from and how they influence one’s perceptions of the world is crucial.

Because very few Swedes think critically about the Jante Law, they are unaware of the reasons why they think the way they do. As Gramsci noted, “The starting point of critical elaboration is the consciousness of what one really is, and ‘knowing thyself’ as a product of the historical process to date which has deposited in you an infinity of traces, without leaving an inventory. Such an inventory must therefore be made at the outset” (Gramsci 2000:326)

If the Jante Law does influence racism, either positively or negatively, then it behooves a society that believes itself to be tolerant and progressive to examine such a cultural norm closely. The awareness of the various loci of power can be surprisingly difficult given how so many things in society that govern people’s actions are taken for granted.

Understanding how the Jante Law functions requires an understanding of where it came from, as well as how and why it came into being. It is for this reason I am creating a historical inventory of the components of the Jante Law that contributed to the social model present today.

Christian teachings were key contributors to the Jante Law, both in name and in effect.#religion

Sandemose deliberately gave the Jante Law ten commandments to call to the reader’s mind the Ten Commandments in Mosaic Law and explained the purpose behind both sets of laws: “In the ancient laws of the land and in the Law of Moses [Moseloven in Norwegian] you will forever detect the spirit of the Law of Jante [Janteloven]; from the Law of Moses, in particular, flow numberless decrees designed to hold the pack in check” (Sandemose 1936:79).

Though Mosaic Law was clearly a contributor, it was only after the Protestant Reformation that the beginnings of the Jante Law started to form in Scandinavia. The dominant religion in Sweden has historically been Lutheranism, and while openly religious people are much less common in the country than in previous times, it is still the largest denomination.

Weber’s analysis of the ideological effects of Protestantism, particularly with regard to self-government, can greatly aid any discussion of Swedish culture.

Weber noted that the acquisition of wealth was not sinful in itself in pious Lutheranism, only the use of it for indulgent purposes (2003:163), and that the surplus wealth allowed capitalism to flourish once this proscription vanished. I posit that in Sweden, piety decreased but the conspicuous display of wealth still remained taboo.

To purchase something beyond the means of your neighbors results in the community believing that you consider yourself of higher standing than they are. People were only “allowed” to purchase what was within the means of everyone in the community. This aversion to materialism became doxa (Bourdieu 1977:164) and was codified into the Jante Law.

Given its religious origins, it is not surprising that the Jante Law retains some of the social functions of the church. Foucault discussed a form of power that came about through Christianity’s organization as a church, which he called “pastoral power.”

It was distinct from the power of the sovereign in that it was focused on the individual’s personal betterment and salvation. Foucault claims pastoral power continued on even after the decline of the church’s influence and today coexists with the power of the modern state. Pastoral power “does not look after just the whole community but each individual in particular, during his entire life.”

More importantly, however, “this form of power cannot be exercised without knowing the inside of people’s minds, without exploring their souls, without making them reveal their innermost secrets. It implies knowledge of the conscience and an ability to direct it” (Foucault 1982:783).

Someone raised with the Jante Law cannot knowingly break it without feeling some measure of guilt or, for lack of a secular word, sinfulness. Greed, selfishness and entitlement are shied away from due to the pastoral power’s influence on an individual’s conscience. The Jante Law influences popular conceptions of what it means to be a good person and in doing so reflects the original functions of pastoral power.

Foucault notes that the modern state does not operate completely apart from the level of the individual, but requires a pre-approved set of behaviors for the individual to follow in order for individuality to be tolerated.

The modern state is, “a very sophisticated structure, in which individuals can be integrated, under one condition: that this individuality would be shaped in a new form and submitted to a set of very specific patterns” (Foucault 1982:783).

The Jante Law essentially is this set of patterns, which people in Nordic countries are expected to follow. It is here that we can see how pastoral power in its contemporary form contributes to governmentality in Sweden.

It is easier for a populace to be governed when they regulate their own behavior and each other’s rather than requiring direct coercion from an institution. This is essentially what governmentality is: a governing of mentality, self-government.

The Jante Law functions as a Gramscian hegemonic system that provides “‘cultural, moral and ideological’ leadership” (Gramsci 2000:423) though without any centralized leader or guiding organizers. While this appears to be a contradictory claim, as hegemony requires moral leadership, what I mean by this is there is no central office or authority that monitors Jante Law infractions.

Leaders in other areas of society, such as business managers, priests and school teachers, can and do exert control and lead in accordance with the Jante Law, but never in its name. Values of humility and constancy are promoted and enforced by such leaders if they themselves adhere to the Jante Law, not because it is mandated by some institution but because it is congruent to their personal values.

People are expected to govern themselves with moral and economic responsibility (Burchell et al 1991:91), something the Jante Law implicitly promotes in its own particular way. However, the parameters of mainstream society people are dictated to follow have changed over time; one of the trends that Swedish social scientists (e.g., Daun 1996) have observed is the decline in the Jante Law’s influence in recent decades.

This is largely attributed to globalization, Americanization and the large number of immigrants moving into the country. With a younger generation consuming media that is antithetical to the Jante Law and people coming from cultures where such a concept is foreign to them, it is losing its hold over society.

Courtesy Google Images

Because hegemonic systems require the continuous renewal of consent of the people to perpetuate themselves, and the Jante Law functions without formal or official leadership, it is gradually fading from the collective memory. It should be repeated, however, that the Jante Law is still alive and well in the early 21st century and though it is not as influential as it once was, it would be a mistake to believe that it is no longer a significant social force.

The Swedish ethnographer Ake Daun has written extensively on the historical background of the Swedish mindset in the late 20th century. Similar to Weber’s argument of a link between Protestantism and the rise of capitalism, Daun posits links between the Church, rural agrarian life and social formations in contemporary Swedish society.

Daun suggests that remnants of ancient beliefs still influence Swedish culture today. He asserts that Swedes view their country as modern and civilized, while countries in the Global South are like Sweden was in the past (Daun 1996:155). This kind of prejudice is indicative of the “new” racism based around cultural rather than biological supremacy that is found in Western societies.

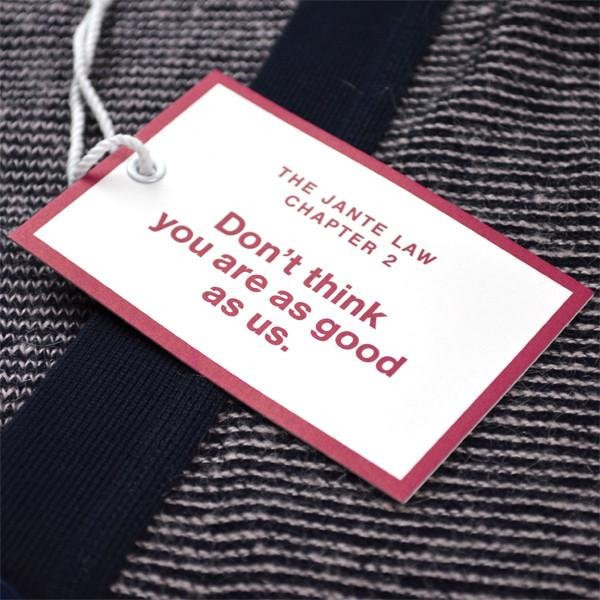

Though prejudice is a nigh universal aspect of human society (Daun 1996:156), covert racism is a part of Western societies that is motivated by the publicly embraced idea that all peoples are equal. Elites and the middle-class generally do not directly admit to their prejudices because racism is now considered a moral flaw (Van Dijk 1993:82).

But rather than actually accept the fact that they have racist opinions and work to change them to remove the moral flaw from their character, many just attempt to exempt themselves from the definition.

Teun Van Dijk’s Elite Discourse and Racism is particularly applicable to Sweden’s context, as it analyzes many of the strategies employed in covert racist discourse.

Narrowly defining or redefining racism in such a fashion as to disqualify one’s own opinions or actions as racist is one such strategy.

The denial of racism by a racist party, as well as by white people in general, implies not only the denial of having committed a social crime or immoral act but also a different definition of racism in the first place. In everyday situations such denials usually pertain to intentions (‘I did not mean it in that way’) or to a different concept of racism (‘I don’t call that racist’). (Van Dijk 1993:82)

This calls to mind what Robinson calls “myths of egalitarianism” (Robinson 2000:26). Racism is bound only to a certain form and thus prejudiced behaviors can be denied by pointing out that such actions are not consistent with the provided definition of racism. In more official circles, racist discourse is hidden in “politically correct” language that allows the message and intent to remain the same.

Lisa Lowe’s work concerning the reception of Asian-Americans in the United States, as visible “foreigners,” has significant parallels to non-ethnic Swedes in Sweden. Both groups report feeling like a foreigner in their own country, regardless of how long they have been in the country or how well they have adapted to the local culture.

Courtesy Google Images

The frequent comments on how good a non-ethnic Swede’s Swedish is—regardless of how long they have lived in Sweden—illustrates some clear parallels to Asian-Americans. Similar to Asian-Americans, a great many (in fact the majority of) non-ethnic Swedes in Sweden were born abroad, but may have been in the country for fifty years in some cases.

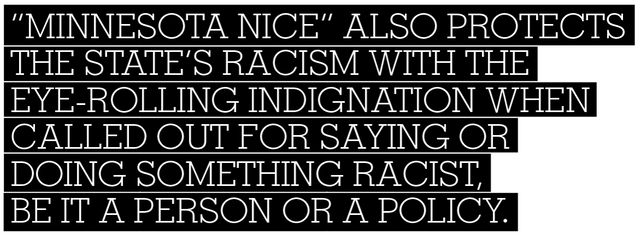

Because whites are more able to blend into Swedish society and not be terribly conspicuous, they do not experience the “perpetual foreigner” effect in the same fashion that people from non-European backgrounds do. Lowe notes (1996:162) that while citizenship implies equal rights for everyone, it is only true on paper and the reality is racialized stratification's in society grant certain people more practical rights than others.

Lowe identifies this as a “racial contradiction” (Lowe 1996:164) where espoused state doctrine differs from the lived experiences of citizens. Employment and housing discrimination are particularly notable examples in Sweden.

Jane Hill’s Everyday Language of White Racism explores this covert racism present in commonplace interactions that demonstrate unspoken prejudices. Hill’s recognition of systems and practices that may reproduce racism without being inherently racially motivated is pivotal in understanding the operation of social formations and can be applied to Swedish society. The reticent nature of Swedes as documented by Daun (1996) can often overlap with the “chilly climate” discrimination (Hill 2008:176) many immigrants and non-ethnic Swedes experience.

What is considered normal behavior on the part of Swedes may be interpreted by those unfamiliar with the culture as Swedes only associating with people like themselves and avoiding contact with those from elsewhere in the world. Hill notes that racism can infuse itself into nearly any social system or discourse (Hill 2008:19) and as a result there is likely a confluence of covert racism and these social codes that lend themselves so easily to prejudiced behavior.

An example from the United States would be whites choosing to live in affluent, all-white neighborhoods for reasons such as investment in a house as real estate or to have access to high quality amenities like parks and schools. Despite non-racial motivations, the effect of residential segregation is the same as if the whites had acted out of racial prejudice. (Hill 2008:26)

Furthermore, prejudiced individuals could easily disguise their motivations by convincing themselves and others that their decisions were based on the aforementioned non-racist motivations.

In the context of the Jante Law, Swedes who do not like living with immigrants may claim they are too haughty and egotistical when there is a genuine clash of personalities, but bigots can also use this excuse to disguise their true motivations. In either case, the effect remains the same: residential segregation.

Eduardo Bonilla-Silva’s research on colorblind racism is particularly applicable to the changes in the social understanding of racism in the post-WWII and post-US civil rights era.

Courtesy Google Images

While the abolition of Jim Crow laws in the US had no direct influence over Swedish society, the shift in what was considered acceptable speech concerning non-ethnic Swedes changed around the same time (Sawyer 2002:30).

Although the context of Affirmative Action questions that frames Bonilla-Silva’s piece is absent in Sweden, the examples of “incoherence” (2002:43) he noticed being exhibited by white Americans when discussing race questions is strikingly similar to the behavior of some of my Swedish interviewees.

Effectively, I am combining practice theory, Foucault’s governmentality, and Marxist takes on critical race theory and ideology. Employing all of these theories to address the various facets of Swedish society influenced by the Jante Law and the arrival of immigrants to the country will hopefully yield insights into the current social climate in Sweden.

The fact that to my knowledge no one has seriously investigated how the presence of the Jante Law informs people’s beliefs on racism is puzzling, as the question seems obvious to me.

Courtesy Google Images

My puzzlement only increased when I read A Fugitive Crosses His Tracks and the main character, Espen Arnakke, is held in jail in the same cell as a black man and recounts to the reader, “The Negro was slavering and rolling his eyes: ‘I never saw the like of how you do act! Just because I’m black, you needn’t go putting on airs and thinking you are better than me!’ This was too much like Jante and more than I could stand” (Sandemose 1936:224).

Arnakke is a native of Jante and had been driven mad by the oppressive dogma of the town to the point where he murdered a man during his travels. The mere hint of plea for humility from the black man so enrages Arnakke that he then attempts to head-butt his cellmate.

In the very book from which the phrase “the Jante Law” originates, the author implies following the Jante Law and regarding people of color as inferior are contradictory concepts.13 Sandemose hinted at the dichotomy between racism and Jante Law equality back in 1936 and this connection has since been forgotten.

I’ll lift your arm and you’ll lift mine, and in a Communist state of mind we’re not worth more than anyone else but surely not worth less.”- Hello Saferide, “2008”

I first came across the Jante Law in my research on Swedish society in preparation for a year studying at Uppsala University as part of an exchange program from the fall of 2005 to the spring of 2006. What I gleaned from books and web searches was that equality and moderation were Swedish values in much the same way it is said individualism and ambition are American values.

Two phrases kept appearing in the literature pertaining to these ideas: Lagom, which I will discuss later, and the Jante Law. Initially, my understanding of what the Jante Law entailed was rather limited and I found the notion of forcing everyone to be exactly the same distasteful.

Upon talking further with Swedes and a few Norwegians I learned that the central component is not to keep people from having different levels of achievement (i.e., not to discourage people from being lawyers rather than cashiers), but to avoid claims that such achievements prove a greater social or moral worth.

Despite its name, the Jante Law is not a literal law but a social code. At its most basic level, it is a cultural model that holds that one should not think he or she is better or more worthy than anyone else. Arrogance and self-aggrandizement are looked down upon while uniformity is valued. This “What-would-the-neighbors-think?” mentality is most often seen when it comes to material goods.

For instance, an individual who recently got a promotion at work might want to buy a Porsche but because everyone else in his neighborhood owns Volvos, his different and expensive car would be taken as a sign of boastfulness—that he believes he is better than others because he got a promotion and wants everyone to know it.

While it is always problematic to claim that everyone from a certain culture thinks or behaves in the same particular way, there are enough commonalities to allow a rough generalization to be made with the caveat that there will always be exceptions.

Though Swedes are less inclined to claim the Jante Law has much sway over Swedish life nowadays, there are numerous contemporary scholars who are confident enough in the continuing influence of the Jante Law in Nordic society to mention them in published works (Avant and Knutsen 1993, Ahmadi 1998, Nelson and Shavitt 2002, Graham 2003, Abram 2008).

The term “the Jante Law” (Jantelagen) was first coined by a Danish/Norwegian author, Aksel Sandemose (1936), and featured prominently in his darkly satirical book, A Fugitive Crosses His Tracks. In the book the author describes a small Norwegian town called Jante, modeled after his own hometown, where a set of “commandments,” known collectively as the Jante Law, are strictly followed. These commandments are:

1. Do not think that you are something.

2. Do not think that you are as good as us.

3. Do not think that you are wiser than us.

4. Do not fancy yourself better than us.

5. Do not think that you know more than us.

6. Do not think that you are superior to us.

7. Do not think that you are good at anything.

8. Do not laugh at us.

9. Do not think that anyone cares about you.

10. Do not think that you can teach us anything.

There is also an eleventh commandment later added as an addendum by the main character in Sandemose’s book: “Do you not think that we know something about you?”

Though Sandemose put a term to this social code, he most certainly did not invent it. The admonition against thinking one is greater than the group is common among small towns and other close-knit agrarian communities like the ones Sweden had in its past.

In his book, Sandemose is scathingly critical of the Jante Law, comparing it to a poison gas that ruins childhoods and calls those that enforce it “the very essence of evil” (Sandemose 1936:83). In Jante, laughter and joy are suppressed as signs of pride; because you are happy when no one else is, you think you know something no one else knows and if you laugh then perhaps you are laughing at someone else.

Injustices frequently go uncorrected because rather than speak out against something, the townspeople would remain neutral and uninvolved.

The novel’s protagonist notes this neutrality is illusory and is effectively siding with those in power, “They strove for domestic peace and delivered the weak unto Moloch” (Sandemose 1936:87) What I discovered from my interviews, though, was that most people today—even its staunchest critics—do not see the Jante Law as something so cruel. At best it reduces haughtiness and at worst it hampers people’s abilities to reach their full potential, but most people do not ascribe malevolence to it as Sandemose does.

In the past, Sweden was very hierarchical and knowing one’s place was highly valued. For example, the expression “Cobbler, stick to your last” also exists in Swedish (Noack and Wigh 2007:30). This value was instilled in the largely agrarian Swedes, who came to believe that people were not supposed to change their station in life and that even relatively small advances in socioeconomic status would be disruptive to the social order.

In the 18th and 19th centuries over 70 percent of Sweden’s population was working in agriculture (Koblik 1975:9) and as a result when the country became industrialized and democratized the views of those farmers held great political influence. Because of this, a sense of egalitarianism emerged among the yeoman farmers, whose values and mindset became dominant in Sweden (Pederson 2009:1261), and consequently a concern over sameness and equality became a part of the national psyche.

Pederson notes that, “the sameness is not founded on socialistic notions about equality, but rather on the feeling that no-one is better than his neighbor” (1262:2009). Thus, a culture that already believes that no one is better than anyone else—and where wealth and materialism are regarded as signs that someone thinks they are better than others—is going to be more inclined to adopt an economic system that favors equality of outcome, or at least equality of opportunity.

Taking cues from Weber’s Protestant Work Ethic, I suggest the origin of the Jante Law and moral equality can be traced back to Lutheranism. Daun (1996) notes the perseverance of Lutheran thinking in Sweden well after the population had shifted to largely secular views. There is irony in that while Weber makes a compelling case for Protestantism priming the pump for capitalism, the same conditions could have given rise to communism instead.36 A population that believes hard work is a virtue in itself, eschews materialist gain and believes that no one can improve or diminish their inherent moral worth would be the ideal for a well-functioning communist society.

Weber attributes a societal decrease in piety around the same time as the Industrial Revolution to the rise of the capitalist system (2003:175), suggesting that if Protestant aversion to materialism and the preoccupation with divine salvation had lasted longer, the reaction to the Industrial Revolution would have been different.

Several informants of Swedish and foreign backgrounds believed nearly every country has a system like the Jante Law (except for the United States, as some of them claim) but only the Nordic countries have put a name to it. While it is certainly true that most cultures have social mores against arrogance and narcissism, the Jante Law is actually more than that.

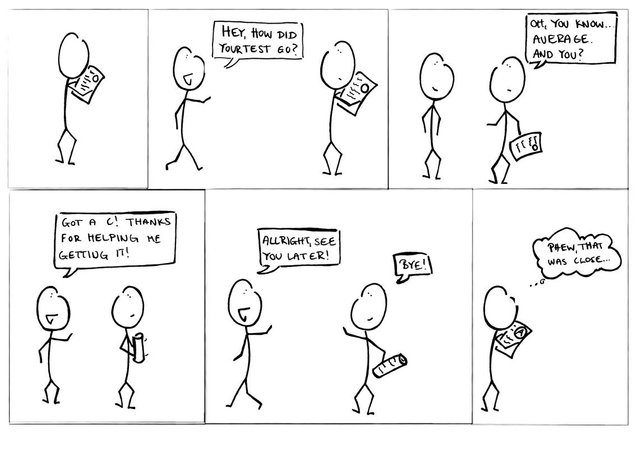

Expressing nearly any form of pride or confidence is unnatural for Swedes under the Jante Law. In the United States it would not be unusual to say, “I make the best brownies!” Though the person would rarely believe their brownies are truly “the best,” he is confident enough in his culinary abilities to proclaim them to others.

In Swedish society, not only would the positive self-assessment not occur, but he might undercut any praise his brownies receive by stating, “Oh, that’s kind of you to say. They’re a little dry, though, don’t you think?”

Many times this is more than false modesty and truly reflects the person’s self-opinion.

Habitus is, as Sherry Ortner, puts it, “a deeply buried structure that shapes people’s dispositions to act in such ways that they wind up accepting the dominance of others, or of ‘the system,’ without being made to do so” (2006:5).

This is an apt description of how the Jante Law functions; people do not think about “the Jante Law” and certainly not about its ten commandments when interacting with others, but behave accordingly most of the time.

Its influences on people’s practices is most readily seen in their spending habits where, as mentioned above, they will eschew more extravagant items in favor of modest ones so their purchases will not arouse envy from their peers.

It informs every person’s individual sensibilities but each individual ends up thinking as the whole (Bourdieu 1977).

This has been recognized for a long time, as the main character in A Fugitive Crosses His Tracks is haunted by the fact that no matter how far away he travels, Jante is always with him. This means that the true influencing power of the Jante Law comes not from others watching and judging you so much as it is a fear that others are doing so.

It functions primarily through self-government rather than through an external apparatus.

While this is a very deeply rooted mindset and set of practices that are part of the normative behavior in Sweden, it is no longer doxic. There is an “awareness and recognition of the possibility of different or antagonistic beliefs” (Bourdieu 1977:164) in Swedish society due to contact with immigrants, particularly in larger cities, as well as the aforementioned prevalence of foreign—especially American—media.

Because doxa is relegated to the “universe of the undiscussed (undisputed)” (Bourdieu 1977:168) a discussion of the merits of such a normative system by its very nature demonstrates the ability to consider alternatives.

One of the main themes in A Fugitive Crosses His Tracks is how detrimental the Jante Law is to a person’s psyche and how bizarre it must seem to those not from Jante.

People are peripherally conscious of the Jante Law and aware that there are other ways of thinking, but they are not always embraced, even by those who are critical of it. The impression I got from several interviews and informal conversations with Swedes is that the Jante Law is a relic of past generations, important to them but not something that anyone younger than perhaps 30 would have incorporated into their worldview.

I was somewhat concerned with this assessment since the literature I encountered and my own observations led me to believe it was still an influential force in society.

My fears that my data were no longer relevant were allayed near the very end of my fieldwork when I went to the small town of Rättvik with several college friends for Midsummer. We stayed at the summer home of one of our friend’s parents, who graciously hosted all eight of us.

At the dinner table the mother began gossiping, “Did you see what the neighbors just bought? Who do they think they are?” One of my friends rejoined, “Yeah, you have to be understanding of other people’s situations.”

Courtesy Google Images

From my perspective as an ethnographer, I believe there are two possible reasons for this response: either she agreed with our host’s view that the neighbors should not have bought something that might be considered ostentatious and therefore conforms to the Jante Law, or she simply said what was socially acceptable rather than speak her mind and is influenced by the Jante Law’s doctrine that one should not draw attention to oneself.

I am inclined, based upon my personal reading of the situation, to believe that the former explanation is the most likely. Calling this social code a “law” strongly hints at there being some kind of enforcement in place. If there were no consequences for violating the Jante Law, not thinking you are someone special would simply be advice rather than a “commandment.”

Depending on the situation, this enforcement may take the form of passive-aggressive behavior, disassociation or sometimes correction through more official channels. Nearly every Swede knows the rules of conduct that accompany the Jante Law, even if they do not know the commandments themselves.

Most people follow them, though there are naturally always some who choose to defy the Jante Law. The Swedes I spoke to told me that among younger generations, the Jante Law is becoming less prevalent as materialism and individualism become more dominant. The trend may indeed be moving in this direction, but it is still the older Swedes who are teaching the young.

Sara, a Swede in her thirties who worked closely with immigrant youths from the suburbs, had a very visible example of how this can affect people at an early age. “I had a meeting with my son’s teacher when he started school. I had to laugh about it because he talks a lot.”

Sara said. “All the time. And he asks questions, always, always and pick[s] up new words and stuff. And when he started school, we had an extra meeting with the teacher and they [she] said, ‘We have a problem with him.’ And I said, ‘What’s the problem?’

[The teacher said] ‘He says strange things.’ And I go, ‘Uh-oh! Bad words!’ And I go, ‘What type of . . . ?’” she laughed and then quoted the teacher, “‘He talks a lot. He says a lot of words that the other children don’t know. And he’s proud of it!’”

“OK.” I said, smiling at the absurdity. “That was the big issue! He had too many complex words, and that was not good.” Sara continued, with a smile on her face, too, “And that’s the one way you can see how the Jantelagen hit the 6-year-old boy who liked to talk, you know? So she wanted us to talk to him to not talk in that way. But we didn’t. He can talk however he wants.”

This provides an excellent example of a child’s interaction with one of Althusser’s Ideological State Apparatuses: the school. The teacher, as an indirect agent of the state, hails the boy as someone she has the authority, even the duty, to impose a set of behaviors upon.

This would make the Jante Law part of an ideology, something taught in schools and reinforced by other members of society. It is a way of thinking that so much of the population has taken to heart that it has become a default way of being, of thinking and behaving. It is important to note that Althusser’s ideology is quite a nuanced concept that includes what might be considered a rational ideology, something deliberate and conscious, and what he calls “material rituals,” which is analogous to habitus.

The Swedish state ideology—that no one is inherently better or worse than anyone else—can be can be rationally explained and framed as part of a belief in human rights, but the habitus that makes a certain vocabulary seem “incorrect” is harder to discuss; it just feels right to do things that way.

The teacher seems to take the Jante Law for granted, not feeling the need to explain why being proud of knowing more is a bad thing or that it might not be considered a problem to everyone. Her attempt (perhaps ultimately a successful one) to influence his speech patterns would likely include not just utilizing a more limited vocabulary but also the typically Swedish reticence.

Before a person is old enough to ask why they are to speak in such a manner, they are socialized into the norm of middle class Swedish speech patterns, which are taken for granted thereafter. If habitus and “material rituals” are comparable concepts and the latter is part of Ideological State Apparatuses, then it is not surprising that the Jante Law can be taught in school (though again, not by name) like conventional manifestations of ideology.

This is congruent to how Marcel Mauss, the author who originally defined habitus, saw this phenomenon function. It is not simply what is passively acquired but also what one is learned through deliberate inculcation. Mauss conceived of it primarily as learned bodily behaviors that one gets from watching others.

“What takes place is a prestigious imitation. The child, the adult, imitates actions which have succeeded and which he has seen successfully performed by people in whom he has confidence and who have authority over him” (Mauss 1934:73).

Not everyone successfully imitates, however, and sometimes those with authority feel the need to address what they see as deficiencies in the child’s actions. For instance, Mauss recalled being reprimanded by one of his teachers for walking like an “idiot” with his hands open (1934:72).

In the case of Sara’s son, however, the ideology dictates acceptable practices of speech and vocabulary, as well as one’s sense of pride or humility. This imposition of a certain moral order on children illustrates how the State, through the school, can influence the mainstream habitus.

Sara had previously explained to me that she came from a background that taught her to be more critically thinking rather than conservative and traditional-minded and as a result the Jante Law was not as important to her as it might be for others.

This can be seen in her decision not to censure her son’s precocious vernacular but she was very adamant that Swedish children, herself and her son included, are instructed not to brag.

Here we see how the Jante Law influences self-government even if one does not agree with the social code. Less traditionally oriented Swedes who “believe that they are something” are still products of mainstream Swedish culture and are encouraged to downplay their achievements, even though they might not be privately encouraged to actually believe their own modest words.

Among adults who decide they are part of the “Us,” the consequences for those they see “breaking” the Jante Law can be much more severe than the aforementioned parent-teacher conferences. This is particularly true for immigrants, who do not know of or understand the Jante Law; they are just working to get ahead in life.

Courtesy Google Images

For many Swedes, immigrants are already outsiders and perhaps viewed with suspicion from day one. For those succeeding and daring to think they are something, the response of Swedes can be surprising.

Grace, a Kurdish woman employed in a government office who has been living in Sweden for around twenty years, made some very intriguing observations. She noticed that the Jante Law’s influence was alive and well in society, particularly with regard to envy over money and material possessions.

The offended individuals assumed their immigrant neighbors were scamming the tax and welfare system to get more money and anonymously reported the alleged infractions to the local authorities. “It’s very funny, you know, it’s quite amazing. I didn’t know about this myself before I got kind of positions. Many things in Sweden are based on somebody calling, like Försäkringskassan (Swedish Social Insurance Agency) Arbetsförmedlingen (The Employment Office), Migrationsverket (The Immigration Bureau) people are calling and saying this person got [money from] skatteverket (The Tax Agency)”

Grace quoted some of these callers in Swedish “‘He’s working for blah.’ ‘He’s in Chile.’ ‘He’s not sick.’ Anonymous tips.” She paused and continued in English. “Do you understand? There are many people calling, ‘Yeah, you know my neighbor, he’s getting money from you but he has a store. He’s working there, he’s earning money there.’”

“Mm, OK. I see, they’re . . . tattling?” I asked. “Yeah! A lot!” It seemed that was the word she was looking for. “More than one can think, you know? Especially after, you know, after these common family weekends, like after Christmas, Easter, then these phones are so much . . . They go warm, people are calling.”

“Huh!”

“So this is kind of Jantelagen, you know? You cannot accept that somebody else can get away with something.” She said, later adding “And they call themselves ‘defender of the good citizenships.’”

Despite what sounded like Swedes accusing their immigrant neighbors of welfare fraud if they appeared too successful, Grace did not see this practice as particularly racist since she understood this as connected to the Jante Law and consistent with how Swedes would behave among themselves.

What is significant to keep in mind is that Grace noted that these anonymous calls occur most frequently after holidays, when gifts and food become visible markers of spending habits. While there would certainly be nothing wrong with reporting a neighbor who is scamming the welfare system, the fact that so many of these calls occur around certain days suggest that they are not based on reasonable evidence and rather the result of assumptions.

It is likely that these anonymous callers are already suspicious of the behavior of foreigners not only to the country, but to the city. Unfortunately, this petty envy and suspicion is the main manifestation of the Jante Law that many immigrants see.

Courtesy Google Images

It is common to distrust and resent people who change their status too quickly, especially if the person already has established friendships and neighborly relations. Swedes do not have a problem with being someone’s subordinate—their society would cease to function if a CEO had equal authority as an entry-level employee—but they generally have difficulty abiding a coworker whom they have known for some time getting a raise or promotion.

This conditional acceptance of status differences is applicable among neighbors, too; if residential areas are generally inhabited by people of the same economic standing and they live together for years, someone who is upwardly mobile can be seen as haughty and if they are advancing themselves too quickly they can be suspected of doing something against the law, as in the case of the immigrants being “tattled on.”

Equality

One of the main research questions that framed my fieldwork dealt with how Swedes could follow the Jante Law, believing they are not better than others, and hold racist opinions at the same time. It seems as though these are contradictory ideas, yet there is little evidence of cognitive dissonance among Swedes regarding this. Indeed, few Swedes had even considered the problem of how these deep-seated, mutually exclusive ideas can coexist.

Fear and mistrust of outsiders have frequently been major contributors to racism throughout history. In everyday discourse xenophobia refers to a fear of foreigners, or people from other countries, but it can operate on a much more local level, down to suspicion of a new neighbor that moved from another town.

Naturally, this xenophobia hinders inclusion into the community and even without any racial or ethnically motivated distrust the newcomer may be regarded as separate from the rest of the neighborhood. A common identity is formed by the more established members of a community; creating an “us” to contrast against a “them” orpossibly a “him” if there is but one outsider.

The Jante Law centers on the individual avoiding the disapproval of an unspecified “Us.” I suggest that how a Swede defines this Us can seriously affect how they view other people in the community. This is best illustrated in relation to the commandment, “Do not think that you are as good as us.”

If the person does not consider herself part of the Us then she will regard this as a statement directed at her and focus more on keeping her own attitude and behavior in line with Swedish norms, whereas if the person counts herself in the Us then she is the one (perhaps not literally) saying it to others and is more likely to be passing judgment on the neighbor who bought a new car.

People (such as immigrants) who are wholly unaware of the Jante Law’s behavioral codes will not be affected by these internalizations but will almost certainly violate the established norms and inadvertently mark themselves as someone who “thinks they are someone.”

This means that Swedes will regard them with suspicion and possibly antipathy over not behaving in a socially acceptable manner. More importantly, someone from outside the community regardless of their ethnicity is automatically not part of the Us while everyone from the community, by default, is.

The different layers and meanings of community play an important role here; if a Swede from Stockholm moves to a small town then he is an outsider, but if a foreigner moves in too then the Stockholmer is part of the community of Sweden rather than an outsider to that specific town.

In this sense “Us” can be taken to mean Swedes as a whole and the command “Do not think that you are as good as us” becomes explicitly xenophobic. If Swedes think they are part of this Us writ large, the Jante Law does not contradict racism but may actually encourage it.

Courtesy Google Images

It should be noted, however, that the broader applications of the Jante Law are usually quite positive. The most significant product of this egalitarian mindset is, of course, Sweden’s gender equality laws as well as its welfare state. “Do not fancy yourself better than us” when spoken by women or the working class becomes an empowering slogan against sexism and classism.

Though wage disparities between men and women still exist in Sweden, the 1995 Human Development Report designated Sweden as the most gender-equal country in the world (Bernhardt et al. 2007:98).

Likewise, access to healthcare and education are rights of all citizens, regardless of their socioeconomic status. It has been said that such ideologies are part and parcel with socialism, that no one is better than anyone else. To a certain degree this is true. I spoke with Zlatko, a middle-aged Bosnian refugee who invited me to the Bosnia-Herzegovina Cultural Association.

Zlatko had lived in Sweden for nearly fifteen years and briefly was a guest worker in Sweden in the 1980s. He explained to me that, for him, the Jante Law was not an alien and bizarre concept as many other immigrants had seen it, but something he was already familiar with in socialist Yugoslavia.

It was unclear, however, if the ideology was taken to heart or simply a slogan to the Bosnians. For mainstream Swedes, these are not just legislations or slogans; the majority of Swedish people truly believe that men and women are equal (Daun 1996:154) and that a poor factory worker has the same rights and value as a wealthy chemist (Daun 1996:179).

Whether or not this equality pertains only to Swedes or is extended to foreigners and non-ethnic Swedes has yet to be determined.

Radical right-wing populist parties have risen all over Europe in response to changing economic and cultural landscapes. These changes have also coincided with immigration from the Global South into Europe and as a consequence many people from groups that may lose from a change in the socioeconomic status quo come to support these right-wing parties.

Swank and Betz (2003) argue that universal welfare states, with their generous and inclusive benefits for the country’s inhabitants, serve to create a political atmosphere that is not conducive to far right parties.

Economic forces aside, societies with universal welfare systems also benefit from “values of equal respect and concern embodied in programmed structure, broadly targeted universal benefits, carefully adapted delivery organizations and participatory administrative processes achieve relatively high levels of contingent consent from the citizenry.

Solidarity, trust and confidence in state intervention are promoted” (Swank and Betz 2003:225).They are quick to note, however, that although the trend of foreign immigration leading to increased support for far right parties is present in all observed European countries—including those with universal welfare—this trend was weakest in universal welfare states (Swank and Betz 2003:239).

These findings corroborate the observations made by Ålund and Schierup that “until recently immigrants [to Sweden] have largely been protected from open forms of populist racism. In this sense their situation has probably been better than in any other European country” (1991:23).

Although the Sweden Democrats (Sverigedemokraterna), a nationalist anti-immigration party, have gained popularity since these two publications came out, they have not yet entered Swedish parliament.

Despite this increase in support, however, the political influence of the Sweden Democrats is not as high as Austria’s Freedom Party (17.5 percent of the votes for the National Council in 2008) or Italy’s Lega Nord (8.1 percent of the votes for the senate in 2008).

The universal welfare state serves as an equalizing force so that the gap between rich and poor is not as great and therefore those who are “better” are not too much better. Even the trust in the state can be seen as a consequence of the Jante Law’s insistence on deference to the greater authority known as “Us.”

Swedes generally trust their government and officials (Bruno et al.2003) or at least believe they have the best interests of the people in mind. The anti- establishment sentiments of certain radical right-wing parties are less prevalent in a society with “Do not think that you can teach us anything” in the back of their minds.

These characteristics are to be expected from a society with the Jante Law. Equality and respect clearly follow from a system where no one is to be thought of as superior to anyone else and concern and support for those who have fallen upon hard times is also a consequence of this mentality.

Just as most Swedes are made uncomfortable at the thought of someone being superior to them, they are similarly bothered at the thought of someone in an inferior position.

The lower position of one person automatically confers a higher position upon another and thus puts Swedes in the undesirable situation of being better than someone else.

Sara clarified this dynamic. “With Jantelagen it’s very hard because you have to blend in in the right way. You know, you have—you can see immigrants who are too humble.”

“How can you—can you be too humble? Can you explain that?” I asked.

Sara said, “If you are too, if you [make] yourself much smaller to the other person, then you if you . . . If I make [myself] smaller—you are Swede now—” she interjected in this hypothetical example, “and if I made [myself] smaller and I say, ‘Oh you are so great, and I am so blah, blah, blah, blah . . . ’” “Ah, OK.”

“Then I will make you feel unsure. And you never make one of the Swedes unsure, you know? We don’t like that, it feels ‘unsafely.’” Sara laughed, “So that’s not good.”

“So you would make them feel unsure by praising them—?” “By praising up. Because we have learned since we were children that we shouldn’t be praised up.”

“Ahh, I see.”

“So then we don’t know. ‘Oh, stop . . . ’” she acted out the classic sheepish response to praise, complete with downward eyes and muttering. “So that’s not good. But if you brag about yourself too much, and if . . . you say, ‘I can take that! I am very good at that! I take that very big, difficult job, ‘cause I’m the best one to do it.’ That’s not good.

So [someone else needs] to say, ‘You should do the job.’”

It is not simply being excessively humble that can disrupt the sense of equality Swedes strive to maintain, but also self-deprecation. This, combined with directly praising a Swede, challenges the Jante Law by identifying people as better or worse than the average person and can potentially invite scorn or envy from any witnesses.

This situation can quickly become even more uncomfortable for Swedes given a general aversion to conflict or disagreement, which would both call attention to oneself and implicitly suggest that one person has something to teach the other.

If a foreigner’s praise is rejected by a Swede and the foreigner repeats it, the Swede would be in an unwinnable situation where they would feel uncomfortable accepting the praise but would feel equally uncomfortable repeatedly contradicting someone.

The only way to know if you're famous in Minnesota is if everybody is trying very hard to ignore you.

Courtesy Google Images

Very interesting. That forcefully imposed "equality" seems to be one of the prizes the progressives in the US are striving for. It would be lovely if they would take the time to read this...

I want to compliment you on the most well-researched and crafted article I have found on steemit so far. I had never heard of Jante's Law, and knowledge of it truly gives me better tools for interacting in this world, that is a wonderful thing.

@fishyculture thank you again. I read your second response before I read the first. Still learning my way around this forum. Thank you. This info definitely allows one to figure out some of the tougher personalities around us. Helps when negotiating. Up-voted Followed.

Thank you!

Thank you @fishyculture. Your praise means a lot to me. In my opinion, Jante is literally at the core of most racial misunderstandings between people of European Descent and all the other nationalities.

This post has received a Bellyrub and 3.54 % upvote from @bellyrub thanks to: @kayleigh-alesta. Send SBD to @bellyrub with a post link in the memo field to bid on the next vote, every 2.4 hours. Be sure to vote for my Pops, @zeartul, as Steem Witness Hope you enjoyed your bellyrub!

Fascinating subject. How different Scandanavia is from Italy, where countless sumptuary laws attempted to keep the mercantiles and peasants from encroaching upon the previlege of their betters! Jante law reminds me of the complex Confucian system of oneway duties that bound the Asians to loyalty to the state and community above all else.

When critiquing a cultural system, please recall that "liberte, fraternite, egalite" are recent concepts. Although the modern West assumes these concepts to be universal good, these concepts are not quite readily accepted as such in most parts of this globe. One could even argue that such concepts are contrary to not only the reality of nature, but also to the divine laws.

You have a unique grasp of this paradigm based on your rich experience. It's nice to know you. Very good comment. Up-Voted and Followed.

Wow that was alot of information...you put alot of work into this post!! I didn't know any of this ...it's very interesting...I enjoyed reading it!! P.S. Thank You!! See you tonight :)

Aw man that stinks, sounds like religion. I was reading for quite a while, like this is really good, then realized I'd only read a 3rd of the article!

Sorry. It was written more for critical thinkers than for someone who is still learning about religion. Better luck next time?

Ouch, Solid burn @knowledge-trust

great post, as usual!

Thanks @five34a4b!

This post recieved an upvote from minnowpond. If you would like to recieve upvotes from minnowpond on all your posts, simply FOLLOW @azziz