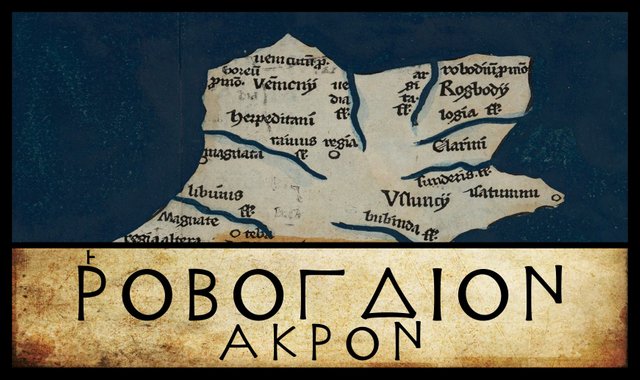

‘Ροβογδιον Ακρον

The final landmark on the east coast of Claudius Ptolemy’s map of Ireland is ‘Ροβογδιον Ακρον, or Cape Robogdion. Today, this is usually identified with Fair Head in the extreme northeast of the island. Ptolemy actually lists Cape Robogdion as the easternmost landmark on the north coast. It is named for a tribe called the ‘Ροβογδιοι [Robogdioi], whose territory may have comprised much of the northern coast.

In his description of the east coast, after listing the Mouth of the River Logia (which I have identified with the River Lagan), Ptolemy writes: after which Cape Robogdion. This leaves open the possibility that Cape Robogdion lies somewhere on the north coast to the west of Fair Head. Over the centuries, it has been identified with Malin Head and Benbane Head, among others.

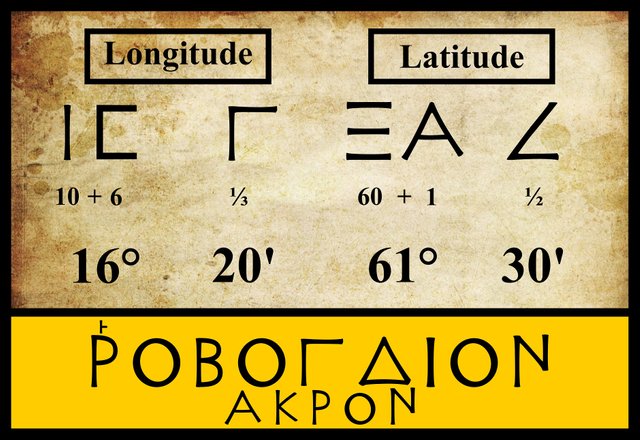

Ptolemy’s Coordinates

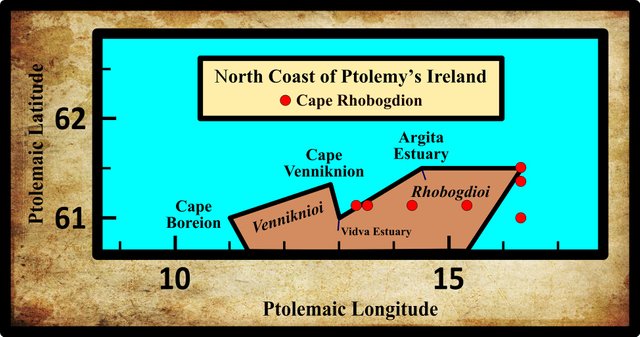

Modern editions and the most reputable manuscript sources (though not Vat Gr 191) are unanimous in the latitude and longitude they assign to Cape Robogdion. Later, less reputable editions and manuscripts, however, have muddied the waters by introducing several variant readings:

| Edition or Source | Longitude | Latitude |

|---|---|---|

| Müller | 16° 20' | 61° 30' |

| Wilberg | 16° 20' | 61° 30' |

| Nobbe | 16° 20' | 61° 30' |

| Vaticanus Graecus 191 | 16° 20' | 61° 10' |

| Σ, Φ,Ψ, 4803 | 13° 20' | 61° 10' |

| Φ | 14° 20' | 61° 10' |

| Editio Argentinensis | 13° 30' | 61° 10' |

| Latin 4805 | 15° 20' | 61° 10' |

| Λ | 16° 20' | 61° 20' |

| A, B, E | 16° 20' | 61° 00' |

Sources: Müller (1883), Wilberg (1838)

Σ, Φ and Ψ are three manuscripts from the Laurentian Library in Florence: Florentinus Laurentianus 28, 9 : Florentinus Laurentianus 28, 38 : Florentinus Laurentianus 28, 42.

The Editio Argentinensis was based on Jacopo d’Angelo’s Latin translation of Ptolemy (1406) and the work of Pico della Mirandola. Many other hands worked on it—Martin Waldseemüller, Matthias Ringmann, Jacob Eszler and Georg Übel—before it was finally published by Johann Schott in Straßburg in 1513.

Latin 4805 is a copy of Jacopo d’Angelo’s Latin translation of Ptolemy’s Geography. It is housed in the Bibliothèque nationale de France [National Library of France] in Paris. Ditto Latin 4803

Λ is a manuscript in the Vatican Library. It was formerly housed in the library of Queen Christina of Sweden, which was purchased by Pope Alexander VIII on her death in 1689. In 1654, Christina caused a national scandal when she abdicated and converted from Lutheranism to Roman Catholicism.

A, B and E are three Greek manuscripts held by the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris: Grec 1401, Grec 1404 and Grec 1403 respectively.

Several of these variants place Cape Robogdion well to the west of Fair Head, as the following diagram shows, lending support to some of the less popular identifications of this landmark.

Variant Readings

A number of variant readings of the toponym ‘Ροβογδιον may be briefly noted.

| Source | Greek | Roman |

|---|---|---|

| N | ‘Ροβογιον | Robogion |

| L | ‘Ροβουγδιον | Robougdion |

| D | Βογδιον | Bogdion |

| Codex Marciani | ‘Ροβονδιον | Robondion |

N is Oxoniensis Seldanus, II, 46, one of the Selden Manuscripts in the Bodleian Library at Oxford.

L is a manuscript in the library at Vatopedi, the ancient monastery on Mount Athos in Greece.

D is another of the Codices Parisini Graeci in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris (Grec 1402).

Codex Marciani is not actually a source for Ptolemy’s Geography, but a manuscript of the Periplus of the Outer Sea by the 4th-century geographer Marcian of Heraclea, who is known to have drawn on Ptolemy.

It is probably safe to dismiss these variants as transmissional errors. The only thing to note about Ptolemy’s orthography of ‘Ροβογδιον is the rough breathing. In ancient Greek, an initial rho, Ρ, always took a rough breathing:

13. Every initial ρ has the rough breathing: ῥήτωρ orator (Lat. rhetor). Medial ρρ is written ῤῥ in some texts: Πυῤῥος Pyrrhus.

14. The sign for the rough breathing is derived from Η, which in the Old Attic alphabet (2 a) was used to denote h. Thus, ΗΟ ὁ the. After Η was used to denote η, one half (ⱶ) was used for h (about 300 B.C.), and, later, the other half (˧) for the smooth breathing. From ⱶ and ˧ come the forms ‘ and ’. (Smyth 10)

So Ptolemy’s ‘Ροβογδιον can be transliterated as both Rhobogdion and Robogdion. The latter is believed to be a better representation of how this name would have been pronounced in ancient Ireland, so this is the form I prefer.

An Early Etymology

William Camden was one of the first to try and identify Ptolemy’s ‘Ροβογδιον Ακρον, and in doing so, he led several of his successors astray. In his Britannia of 1607, we read:

Upon [Lough Foyle], formerly, stood Derry, a Monastery, and a Bishop’s See ... The Robogdii, seated above Logia [which Camden identified with Lough Foyle], possessed all this northern coast ... Here, in Robogh, a small Episcopal Town, are the remains of the old name Robogdii. As for the Promontory Robogdium, I cannot tell where to fix it, unless it be Faire Foreland. From this rocky place, the shore winds back by the mouth of the Lake Swilly, which Ptolemy seems to call Argita. (Camden 1722:1410-1411)

Camden’s Faire Foreland must be Fair Head in County Antrim, though his subsequent description of the shore winding from this rocky place back by the mouth of Lough Swilly almost seems to imply that he is actually thinking of Malin Head (see Darcy & Flynn 58, and Martin 299, who both draw this conclusion).

But where was Camden’s Episcopal Town Robogh? According to the 19th-century Irish antiquary Thomas Wood, it was in County Antrim:

I suppose the Robogdii to have been the Rhedones of Celtic Gaul; who, in consequence of their maritime skill, [and] the construction and size of their vessels, were enabled to pillage the southern coasts of Ireland. Remains of this tribe appear in the word Robogh, the name of a small episcopal town in Antrim. (Wood 44)

I have never heard of any such place as Robogh, nor have I been able to find it on any map, ancient or modern. I believe Wood has simply assumed that it must have been in County Antrim since that is where Camden’s Fair Foreland was situated. But Camden’s description of Robogh as an Episcopal Town occurs in a chapter entitled The County of Donegall or Tir-Conel. This suggests that he was actually referring to Raphoe, a town in County Donegal that has been an episcopal seat for centuries:

The foundation of the See of Raphoe must in all probability be dated from the tenth century. (Brenan 253)

According to a Mr Whitaker, one of the sources for the 4th through 6th editions of the Encyclopaedia Britannica (1801-23), Robogh was the ancient name of Raphoe:

Upon the northern shore and along the margin of the Deucaledonian ocean were only the Robogdii, inhabiting the rest of Donegalle, all Derry, and all Antrim to the Promontory Fair-Head and the Damnii, giving their own name to the Fair-Head and to the division of Raphoe, having the rivers Vidua or Shipharbour, Argita or Logh Swilly, Darabouna or Logh Foile, and Banna or Ban in their territories, and acknowledging Robogdium, Robogh, or Raphoe for their chief city. (Whitaker, and Encyclopaedia Britannica, Volume 11, p 323)

An online search identified this Mr Whitaker as the controversial English historian John Whitaker, whose extravagant theories on the early history of these islands have long since fallen out of favour with the academics. The source of these details is The History of Manchester, believe it or not! His derivation of Raphoe from Robogh cannot be taken seriously. Raphoe actually derives from Ráth and both, meaning ringfort and hut or cell. Its name appears in Irish annals as Rath-both (Joyce 304). The town originated as a monastic settlement in the 6th century and cannot possibly have anything to do with Ptolemy’s Robogdion. Not surprisingly, Mr Whitaker’s contributions do not appear in later editions of the Encyclopaedia Britannica!

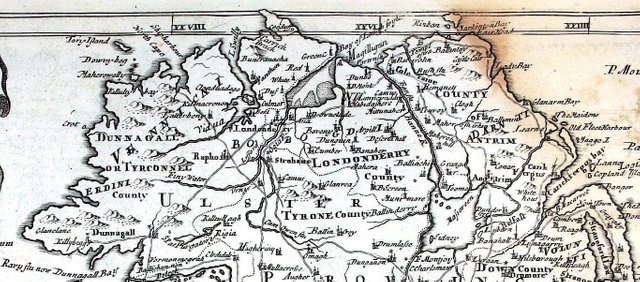

In 1673 the cartographer Richard Blome brought out what is little more than an epitome of Camden’s Britannia, under the near-identical title, Britannia: or A Geographical Description of the Kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland, with the Isles and Territories thereto belonging. His brief description of County Donegal runs as follows:

TIR-CONEL, or DUNAGAL, a Champain Country, and well watered with Rivers and Loughs, which discharge themselves into the Sea, which washeth its Southern, Western, and Northern parts, and affords to the Inhabitants great plenty of fish and River-fowl. It is divided into five Baronies, viz. Tirhugh, Boylagh, Killmacreanan, Raphoe, and Enishowen: And hath for its chief places

Derry, or London-Derry, a Colony of Citizens of London; a fair and well-built Town, where some time stood a flourishing Monastery.

Dunegall, which gives name to the County, seated on a Bay of the Sea, where it hath good Haven, and between the mouth of Lough-Earne, and Balewilly-bay [ie Inver Bay].

Calebeck, situate on the Sea, where it hath a commodious Haven, and Robogh.

Along the Coast of this County are seated several small Isles, viz. Torr-Isle, the Isles of Claddagh, North-Aran, &c. also the Promontories of Fair-foreland, Rams-head, and St. Hellens-head: And in this County is St. Patricks Purgatory, a Vault or narrow Cave in the ground, of which strange fancies are believed by the simple sort of the Irish. (Blome 309-310)

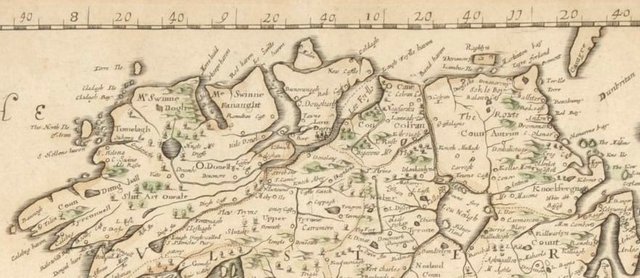

Note that Blome places Fair Foreland in County Donegal, probably meaning Malin Head. Also, he refers to the barony as Raphoe but lists a town under the name Robogh. It appears that Blome, like Wood, simply misread or misunderstood Camden. He mistakenly assumed that Camden’s Robogh and Fair Foreland were both in County Donegal—a pardonable mistake, given the ambiguity of Camden’s description—and failed to recognize Robogh as Raphoe. Curiously, Blome’s Mapp of the Kingdome of Ireland that accompanies his text contains neither Robogh nor Raphoe, and correctly identifies Fair Head in County Antrim as Fayre forland:

Walter Harris correctly understood Camden to mean Raphoe when he wrote of Robogh, and Fair Head when he wrote of Faire Foreland, but he agreed with James Ware (whose work he was editing when he made this comment) that Malin Head was the place Ptolemy meant:

The Situation in Ptolemey will not admit this Promontory to be the Fair-Fore-Land, as Camden judges it to be. Rath-both, now called Raphoe, seems to carry some Foot-steps [ie vestiges] of the Robogdii in it. (Ware 43)

So what is the solution of this Robogh mystery?

Lazy translation. In the original Latin version of Camden’s Britannia, what he actually wrote was:

Inter hos Rabogh viculus Episcopalis antiqui Robogdiorum nominis expressa retinet vestigia. (Camden 1616:709)

Among these, Rabogh, an episcopal village, retains clear vestiges of the ancient name of the Robogdioi.

Camden wrote Rabogh, not Robogh, which strengthens the argument that he was referring to Raphoe.

One of the earliest modern maps of Ireland is John Speed’s Map of the Kingdome of Ireland, which appeared in his atlas Theatrum Imperii Magnae Britanniae [The Theatre of the Empire of Great Britain], published in 1611-12. On this map, Fair Head is Fayre forland Promontory. Raphoe is not included, nor anything resembling Robogh or Rabogh. It is probably fair to say that Richard Blome had Speed’s map at his elbow as he drafted his own map of Ireland.

To conclude this wild-goose hunt, we turn to William Baxter, the Welsh antiquary. In this series we have already had occasion to quote from his 1719 dictionary of British antiquities, Glossarium Antiquitatum Britannicarum, sive Syllabus Etymologicus Antiquitatum Veteris Britanniae atque Iberniae temporibus Romanorum. Under the heading Robogdium Promontorium, we read:

Robogdium Promontory in Ptolemy, seen by Camden to be Fair Foreland, or the spectacular headland in the territory of the Voluntii. In the dialects of the ancient Brigantes, Re, Ri and Ro were used interchangeably for Rac or Rhag, meaning before, in front of; it also contains üog diü, or wave of water; so that Robogdium might mean before the wave of the sea. (Baxter 204)

Modern Etymologies

More recently, linguists have suggested quite different etymologies for Ptolemy’s ‘Ροβογδιον:

Ροβογδιον ακρον (Robogdion 2,2,2) was probably Fair Head, the north-north-eastern tip of Ireland opposite Rathlin Island (Ptolemy’s Ρικινα), though one cannot totally rule out other extremities, including Benbane Head (near the Giant’s Causeway) or Runabay Head. The name probably meant something like ‘great curve’, referring to the general shape of the coastline, where –bogd- (seen also in Medibogdo) probably came from *bheug- ‘to bend’, which led to OE boga ‘bow’. This rejects the Celticists’ theory that Ροβογδιοι people were ‘mighty fighters’, but retains their idea of initial Ro- as ‘great’, which might have evolved from PIE *per- ‘to pass over’, via *pro- then loss of initial P, or from PIE *ghreu- ‘to grind’, the source of words such as gross and great, which lost an initial GH sound. (Roman Era Names)

We will return to this question when we come to discuss the Robogdioi, the tribe for whom the headland is named.

Other Headlands

Malin Head (or, to be precise, Banba’s Crown) is the most northerly point on the island of Ireland, and over the centuries there have been a few scholars who have identified it with Ptolemy’s ‘Ροβογδιον Ακρον:

James Ware, the Irish antiquary: The extreme Promontory of all Ireland, hanging over the Deucaledonian or Northern Sea, in the Peninsula of Inis-owen. (Ware 43)

Walter Harris, who edited the complete works of Ware, agreed with Ware’s identification, as we saw above.

Charles Trice Martin: Fair Foreland, now called Malin Head, co. Donegal (Martin 299). I have found no independent evidence that Malin Head was ever called Fair Foreland. I believe that Martin, like Richard Blome before him, has simply misread William Camden.

Louis Francis regards Rathlin Island as a better fit for Ptolemy’s Robogdion than Fair Head, though he does not rule out the latter.

| Fair Head | Malin Head | Rathlin |

|---|---|---|

| Camden (1607) | - | - |

| - | Ware (1654) | - |

| Müller (1883) | - | - |

| - | Martin (1892) | - |

| Orpen (1894) | - | - |

| - | - | Francis (1994) |

| Darcy & Flynn (2008) | - | - |

Source: Darcy & Flynn 57

References

- William Baxter, Glossarium Antiquitatum Britannicarum, sive Syllabus Etymologicus Antiquitatum Veteris Britanniae atque Iberniae temporibus Romanorum, Second Edition, London (1733)

- Richard Blome, Britannia: or A Geographical Description of the Kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland, with the Isles and Territories thereto belonging, Richard Blome, London (1673)

- William Camden, Britannia siue Florentissimorum Regnorum Angliae, Scotiae, Hiberniae et Insularum Adiacentium ex Intima Antiquitate Chorographica Descriptio, Ruland, Frankfurt am Main (1616)

- William Camden, Britannia: Or A Chorographical Description of Great Britain and Ireland, Together with the Adjacent Islands, Second Edition, Volume 2, Edmund Gibson, London (1722]

- Robert Darcy & William Flynn, Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland: A Modern Decoding, Irish Geography, Volume 41, Number 1, pp 49-69, Geographical Society of Ireland, Taylor and Francis, Routledge, Abingdon (2008)

- Patrick Weston Joyce, The Origin and History of Irish Names of Places, Volume 1, Longmans, Green, & Co, London (1910)

- Marcian, Karl Müller (editor), Geographi Græci Minores, Volume 1, Firmin-Didot, Paris (1882)

- Charles Trice Martin, The Record Interpreter: A Collection of Abbreviations, Latin Words and Names Used in English Historical Manuscripts and Records, Reeves and Turner, London (1892)

- Karl Wilhelm Ludwig Müller (editor & translator), Klaudiou Ptolemaiou Geographike Hyphegesis (Claudii Ptolemæi Geographia), Volume 1, Alfredo Firmin Didot, Paris (1883)

- Karl Friedrich August Nobbe, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographia, Volume 2, Karl Tauchnitz, Leipzig (1845)

- Goddard H Orpen, Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland, The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Volume 4 (Fifth Series), Volume 24 (Consecutive Series), pp 115-128, Dublin (1894)

- Claudius Ptolemaeus, Geography, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vat Gr 191, fol 127-172 (Ireland: 138v–139r)

- Herbert Weir Smyth, A Greek Grammar for Colleges, American Book Company, New York (1920)

- John Speed, The Theatre of the Empire of Great Britaine: Presenting an Exact Geography of the Kingdomes of England, Scotland, Ireland, and the Adjacent Islands, (1611-12)

- James Ware, Walter Harris (editor), The Whole Works of Sir James Ware, Volume 2, Walter Harris, Dublin (1745)

- John Whitaker, The History of Manchester in Four Books, Book the First, London (1771)

- Friedrich Wilhelm Wilberg, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographiae, Libri Octo: Graece et Latine ad Codicum Manu Scriptorum Fidem Edidit Frid. Guil. Wilberg, Essendiae Sumptibus et Typis G.D. Baedeker, Essen (1838)

- Thomas Wood, Fable and Fact in the Early Annals of Ireland, and on the Best Mode of Ascertaining What Degree of Credit These Ancient Documents Are Justly Entitled to, The Transactions of the Royal Irish Academy, Volume 13, pp 1-79, Royal Irish Academy, Dublin (1818)

Image Credits

- Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland: Wikimedia Commons, Nicholaus Germanus (cartographer), Public Domain

- Greek Letters: Wikimedia Commons, Future Perfect at Sunrise (artist), Public Domain

- Fair Head, County Antrim: © 2018 Outdoor Concepts, Fair Use

- The Kingdome of Ireland (Morden 1695): Robert Morden (cartographer), Public Domain

- A Mapp of the Kingdom of Ireland: © James Adam & Sons Ltd, Richard Blome (cartographer), Fair Use

- Northwest Ireland: © Cambridge University Library, John Speed (cartographer), Fair Use

- Complete Scream, Fair Head: Wikimedia Commons, © Cbabak, Creative Commons License

- Fair Head, Antrim: © Rossographer, Geograph Ireland, Creative Commons License

I see that you have put a lot of work into posting. Upvote for You:)

IT IS BIG INFORMATIVE POST MAN

Great what you share, my friend, the history of Ireland is too interesting, it's good that very qualified historians like you have the passion to share all the knowledge with the community

Very good written friend thanks for sharing fantastic stories

Thats one is awesome

You have forgot me dear friend

its awesome post. the photo you created in this post makes enough description for steemians. people will see your work and that was a great educational post about Ireland and its history. the archaeology you created is amazing brother. you will success with good . thanks a lot for this post. it was a great knowledge for all. thanks