Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland – Part 1

In an earlier article in this series I looked at the Geography of Claudius Ptolemaeus—Ptolemy—to see what could be learnt from it concerning the early history of Ireland. On that occasion I drew mainly upon Robert Darcy and William Flynn’s interpretation of Ptolemy’s text (Abingdon 2008). Now I would like to return to the Geography and examine Ptolemy’s data for myself.

The original Greek title of the work—Γεωγραφικη Ὑφηγησις, Geōgraphikē Hyphēgēsis—means Geographical Guidance, but it could be translated literally as World-Drawing Guide: the Geography is essentially a map-making kit (Berggren & Jones 4, 5). Let us see, then, if we can construct a map—not of the world but of Ireland—simply by following Ptolemy’s instructions.

This may be a hopeless endeavour. The earliest surviving manuscript of the Geography is a 13th-century fragment of Book 8 in the Vatican Apostolic Library (BAV Vat. gr. 177). Between the original work and our oldest copies of it lie more than a thousand years of editing, copying, redacting and emending what Ptolemy—allegedly—wrote:

A third obstacle is the degree to which different manuscripts diverge in the versions that they present of parts of the Geography, which is one reason why no satisfactory edition of the whole text of the work has been achieved in modern times. There can be no doubt that the Geography was badly served by its manuscript tradition; the most conscientious scribe was certain to introduce numerous errors in copying its interminable lists of numbers and place names, and some copyists did not resist the temptation to “emend” the text. The instability of the textual tradition chiefly affects the geographical catalogue and the captions for the regional maps. (Berggren & Jones 5)

Latitude

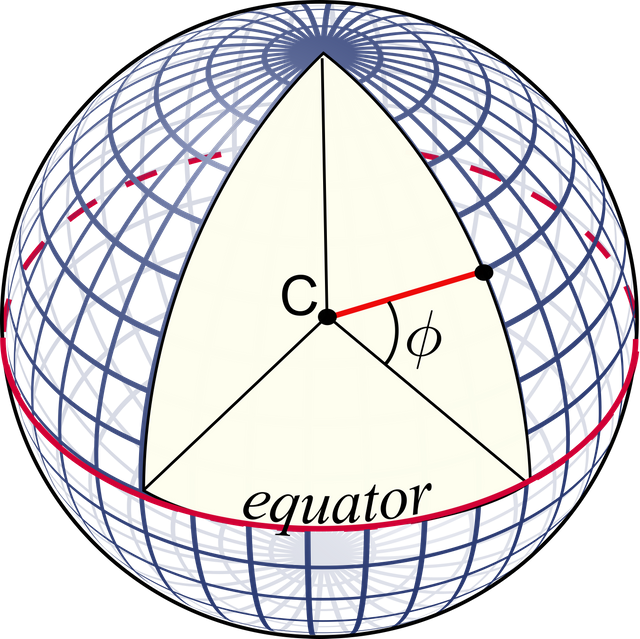

Ptolemy’s concept of geographical latitude is essentially identical to that of modern cartographers. The latitude of a location on the surface of the Earth is defined as the angle measured at the centre of the Earth between that location and a point on the equator due north or south of that location. Locations that lie due east or due west of a given location share the same latitude as that location. All such locations are said to lie on the same parallel of latitude. These parallels are circles on the surface of the Earth, which Ptolemy modelled as a perfect sphere. The equator is the largest such parallel of latitude. As we move closer to the poles, the radii of these circles of latitude decrease. The North and South Poles might be described as circles of latitude of zero radius.

The only significant difference between Ptolemy’s definition of latitude and our modern concept of it involves the slight difference between the shape of the Earth in Ptolemy’s model and the figure of the Earth used by cartographers today. The former is a perfect sphere, whereas the latter, known as the reference ellipsoid, is an oblate spheroid. For a map of Ireland, however, the discrepancy between these two models is negligible and may be safely ignored.

There is, however, a much more significant discrepancy between the Ptolemaic model of the Earth and the modern globe. Ptolemy underestimated the radius of the Earth by about 16.75%. He reckoned that one degree measured along a great circle (such as the equator) was 500 stadia. Ptolemy’s stadion was about 185 metres long:

He estimated one degree to be 500 stadia (1:7:1, 1:10:1, 1:11:2, 7:5:12). But he never said explicitly how long the stadion was. From this it has been concluded—correctly, I believe—that it was a commonly accepted measure, and did not need to be explicitly defined. Therefore, only the stadion of 185 m, or 1/8 m. p. [one eighth of a Roman mile], is meant. (Cuntz 110-111, my translation. 1:7:1 means Book 1, Chapter 7, Section 1 of the Geography, etc.)

A simple calculation shows that Ptolemy estimated the circumference of the Earth to be

Our current estimate—measured along a great circle passing through Alexandria and Ireland and corrected to three significant figures—is 40,000,000 m, so Ptolemy’s estimate is about 16.75% too small. In other words, Ptolemy’s Earth is 0.8325 times as big as our Earth. Does this mean that once we have reconstructed Ptolemy’s map of Ireland, we should resize it by a factor of about 83.25%? We shall see.

Longitude

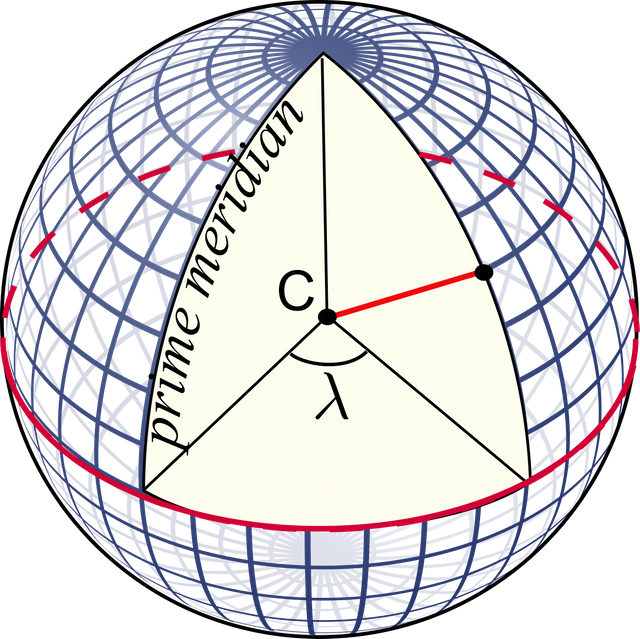

Ptolemy’s concept of longitude is also essentially the same as the one adopted by modern cartographers. The difference in longitude between two locations on the surface of the Earth is equal to the angle subtended at the centre of the Earth between two points on the equator one of which is due north or south of one of the two locations and the other of which is due north or south of the other location. If this angle is zero degrees—that is, if one of the two locations lies due north of the other—then we say that the two locations lie on the same meridian of longitude. Meridians of longitude are great semicircles that run from the North Pole to the South Pole.

In order to assign a location an absolute longitude, however, it is first necessary to choose a reference or prime meridian—that is, a meridian to which we arbitrarily assign a longitude of 0°. For historical reasons, modern cartographers use the meridian that passes through the Airy transit circle at the Royal Observatory, Greenwich. Ptolemy chose the westernmost location on his map—the Islands of the Blest—to define his prime meridian. While the identity of these islands is disputed, Ptolemy does tell us (8:15) that his prime meridian lies sixty degrees west of Alexandria. The longitude of Alexandria in modern coordinates is almost precisely 30° E (the ancient Library of Alexandria was located at 29.89° E longitude), so Ptolemy’s prime meridian corresponds closely to our meridian 30° W of Greenwich.

In Book 4, Chapter 5, however, Ptolemy gives 60° 30' as the longitude of Alexandria (Cuntz 106). This is probably a more precise estimate, and is therefore the one I will be using.

The Data

Because Ptolemy chose to begin his description of the known world—the oikumene—in the extreme northwest, Ireland was given pride of place in the Geography. Book 2, Chapter 2 comprises the coordinates for thirty-one locations in Ireland and nine offshore islands, and the approximate positions of sixteen tribes:

- 15 river mouths or estuaries

- 5 promontories or headlands

- 4 coastal settlements or towns

- 7 inland settlements or towns

- 9 islands

- 16 tribes

There is some dispute over the nature of one of Ptolemy’s Irish locations (Isamnion), which is given in some manuscripts as a promontory and in some as a coastal settlement:

It is doubtful whether ’Ισάμνιον (Isamnion) was a town or a promontory, probably the former, as Marcian reckons eleven towns and five promontories in Ireland, which agrees with Ptolemy if Isamnium is taken as a town. (Orpen 126, Marcian & Müller 561)

Either way, Isamnium was a coastal location.

The following chapter of the Geography, 2:3, details Albion, or Britain, and its neighbouring islands (including Thule). Taken together, Ireland and Britain constitute the first of Ptolemy’s twenty-six regional maps.

What do we know of Ptolemy’s sources for his Irish data:

Ptolemy tells us it was reasonable to use locations “obtained through the more accurate [ie astronomical] observations, as foundations, so to speak, but to fit [the features] that come from the other [kinds of data] to these, until their positions with respect to each other and to the first [features] stand as much as possible in agreement with those reports that are less subject to error” (Ptolemy, Geography, Book 1, p. 4 quoted in Berggren and Jones 2000, p. 63). The “other kinds of data” are traveller, merchant and military reports of distances and directions collected by previous geographers, notably Marinos of Tyre ... The result is the latitude and longitude of approximately 8000 locations from Ireland through China ... Ptolemy’s map of Ireland is a long exposure photograph in the sense that it most likely represents points recorded not instantaneously but over time, written down and fixed at roughly AD 100. Ptolemy references 15 rivers, six promontories and ten cities. He names and gives the proximate locations of 16 tribes ... Of Ptolemy’s specific information on Ireland, or its sources, we know nothing. (Darcy & Flynn 50)

The Irish Celticist T F O’Rahilly would beg to differ. More than seventy years ago he pointed out that Ptolemy’s specific information on Ireland, when compared with his data for Britain, was several centuries out of date. For example, there is no trace in Ptolemy’s data of two of the principle Celtic races of Ireland, the Lagin and the Goidel, who had certainly colonized the island by Ptolemy’s time:

... the most striking feature of Ptolemy’s account of Ireland is its antiquity. The Ireland it describes is an Ireland dominated by the Érainn, and on which neither the Laginian invaders nor the Goidels have as yet set foot. The language spoken in it was Celtic of the Brittonic type (p. 17). (O’Rahilly 39-40)

While the evidence of the names in Ptolemy’s account of Ireland shows plainly that the Ireland he describes was a Celtic-speaking Ireland, none of the names has anything peculiarly Goidelic about its form. On the contrary, there is positive evidence to show that the Celtic spoken in Ptolemy’s Ireland was of the Brittonic type. (O’Rahilly 17)

O’Rahilly surmised that Ptolemy’s principle source of information on Ireland was the lost work of Pytheas of Massalia, who is believed to have visited Ireland around 325 BCE—sufficiently early to have preceded both the Laginian and the Goidelic settlers.

O’Rahilly’s reasoning is indefeasible, and in the seventy-odd years since the publication of his Early Irish History and Mythology no one has refuted his claim. Nevertheless, most scholars who have come after him have simply ignored what he had to say about Ptolemy’s sources. Flynn and Darcy, whom I quoted above, published their work in 2008 and cite O’Rahilly several times. John Waddell, in The Prehistoric Archaeology of Ireland (2000), also cites O’Rahilly in connection with Ptolemy, but can still write:

Early in the 1st century AD, Philemon recorded from merchants that the length of the island of Ireland was twenty days’ journey, a reasonably accurate estimation if an average daily journey of 21 miles (33 km) is accepted. Philemon was probably one of the sources for Ptolemy`s Geography compiled in Alexandria in the 2nd century AD. (Waddell 373)

Waddell is here following another scholar of Celtic studies, J J Tierney. Writing in 1976, Tierney also identified Philemon, a geographer of the mid-1st century CE, as Ptolemy’s principal source:

The question is finally considered from which earlier authorities the detailed geographical information in Ptolemy, Geography II 2 is derived and the conclusion is put forward as probable that very little of Pytheas survives whereas the mass of the material comes from Philemon who derived his information from contemporary merchants belonging to the islands or the adjacent continental area. (Tierney 257)

Tierney does not even mention O’Rahilly, let alone attempt to refute him. Both men worked for the Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies.

It is true that Ptolemy cites Philemon as a source for the length of Ireland (Ptolemy 1:11:7), but this is the only reference to him in connection with Ireland. If Philemon were the source of Ptolemy’s ethnographic, geographic and toponymic information on Ireland, the Geography would not lack all mention of the Laginian and Goidelic settlements. If Pytheas was not Ptolemy’s principal source, then some other early explorer, such as the Phoenician Himilco, must have been.

Ptolemy’s description of Britain includes several references to the Dumnonii (2:3:2, 2:3:7, 2:3:8, 2:3:13), who were closely related to the Laginians, and may even have colonized parts of Britain from Ireland (O’Rahilly 93-94, 130). There is clearly a disparity between Ptolemy’s sources for Britain and his sources for Ireland. In an earlier article I also pointed out that Ptolemy’s description of Ireland fails to mention the Newgrange complex of megalithic structures, or anything that could possibly be identified with it—another indication that his information was centuries out of date.

To be continued ...

References

- J Lennart Berggren, Alexander Jones, Ptolemy’s Geography: An Annotated Translation of the Theoretical Chapters, Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ (2000)

- Otto Cuntz, Die Geographie des Ptolemaeus: Galliae, Germania, Raetia, Noricum, Pannoniae, Illyricum, Italia, Weidmann, Berlin (1923)

- R Darcy & William Flynn, Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland: A Modern Decoding, Irish Geography, Volume 41, Number 1, pp 49-69, Geographical Society of Ireland, Taylor and Francis, Routledge, Abingdon (2008)

- Marcian of Heraclea, Karl Müller (editor), Periplus Maris Exteri, Firmin Didot, Paris (1855)

- Karl Wilhelm Ludwig Müller (editor & translator), Klaudiou Ptolemaiou Geographike Hyphegesis (Claudii Ptolemæi Geographia), Volume 1, Alfredo Firmin Didot, Paris (1883)

- Thomas F O’Rahilly, Early Irish History and Mythology, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, Dublin (1946)

- Goddard H Orpen, Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland, The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Volume 4 (Fifth Series), Volume 24 (Consecutive Series), pp 115-128, Dublin (1894)

- Claudius Ptolemaeus, Geography, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vat Gr 177

- J J Tierney, The Greek Geographic Tradition and Ptolemy’s Evidence for Irish Geography, Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy: Archaeology, Culture, History, Literature, Volume 76, pp 257-265, Royal Irish Academy, Dublin (1976)

- John Waddell, The Prehistoric Archaeology of Ireland, Wordwell Ltd, Bray (2000)

- Friedrich Wilhelm Wilberg, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographiae, Libri Octo: Graece et Latine ad Codicum Manu Scriptorum Fidem Edidit Frid. Guil. Wilberg, Essendiae Sumptibus et typis G.D. Baedeker, Essen (1838)

Image Credits

- Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland and Britain: Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain

- Ptolemy’s Geography: © Princeton University Press, Fair Use

- Latitude (ϕ) as Defined by Ptolemy: Wikimedia Commons (adapted), Public Domain

- Die Geographie des Ptolemaeus: Public Domain

- Longitude (λ) as Defined by Ptolemy: Wikimedia Commons (adapted), Public Domain

- Goddard H Orpen: Copyright Unknown, Fair Use

- Irish Geography: © Geographical Society of Ireland, Fair Use

- T F O’Rahilly: Unknown Copyright, Fair Use

- John Waddell: © 2017 National University of Ireland, Galway, Fair Use

- Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy: © RIA, Fair Use

a very useful history to know ... thanks for the information has increased our insight.

You're welcome.

I lived in Ireland, the city of Cork, for a year.

It's a wonderful place with wonderful people! The weather was only so so, but the rest made up for it.

FYI... Upvoting replies to your posts, really helps the person replying (and you) so if you would upvote this reply - Thank you. :)

Thank you. I always upvote replies.

@harlotscurse Awesome posts sir... I thoroughly concur along with you. Adore it. Upvoted.

Thank you. Upvoted.

Very excellent post dear

@harlotscurse thnx for putting this information all with each other. Followed.

Thank you.