Ἐρδινοι

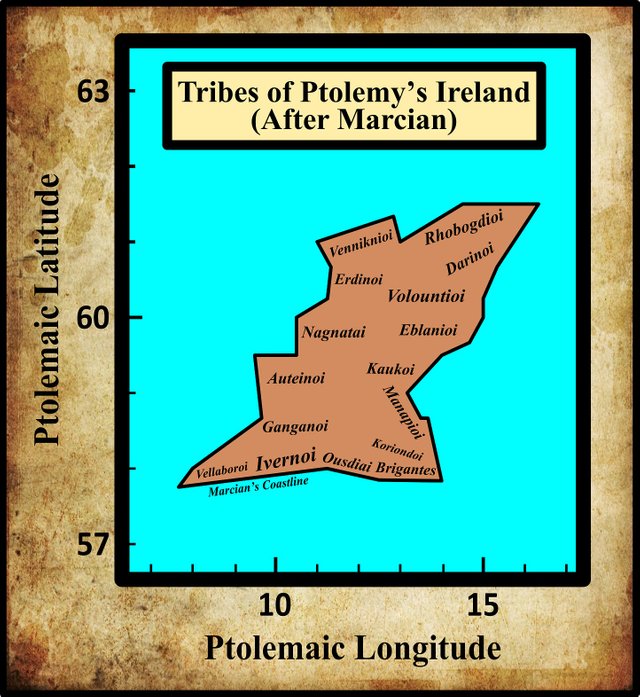

In his description of Ireland, Geography 2:2 §§ 1-10, Claudius Ptolemy records the disposition of sixteen Irish tribes. Beginning, as before, in the southeast corner of the island and proceeding in a counterclockwise direction, the tenth of these are the Erdinoi (Latin: Erdini). Ptolemy places there on the west coast, immediately south of the Venniknioi.

In his 1883 edition of Ptolemy’s Geography, Karl Müller noted several variant readings of this ethnonym, but some of these differ from one another only in the application of the Greek accents. As the use of these accents was not regularized until the Byzantine era, they are generally considered to be “without authority” (O’Rahilly 1 fn 2, Gnanadesikan 220-221). This reduces the number of genuine variants to two. The second of these differs from the first only in the use of the rough breathing, but I have included it, as Ptolemy is thought to have employed marks for smooth and rough breathing in cases where the pronunciation was not obvious to his readers (Gnanadesikan 220):

| Source | Greek | English |

|---|---|---|

| Most MSS | Ἐρδινοι | Erdinoi |

| D, E, Ξ, Σ, Φ, Ψ, M, N, V, X, 4803, 4805 | Ἐρπεδιτανοι | Erpeditanoi |

| B, C | Ἑρπεδιτανοι | Herpeditanoi |

B is one of the Codices Parisini Graeci in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris: Grec 1404. B gives the variant reading Ἐρπεδιτανοι [Erpeditanoi], but in the margin someone has added: Ἐρδινοι οἱ και Ἑρπεδιτανοι [the Erdinoi and Herpeditanoi].

C is Parisiensis Supplem 119. Presumably this is one of the Codices Parisini Graeci in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris, though I have not been able to confirm this. Like B, C gives the variant reading Ἐρπεδιτανοι [Erpeditanoi], but in the margin someone has added: Ἐρδινοι οἱ και Ἑρπεδιτανοι [the Erdinoi and Herpeditanoi].

D and E are two of the Codices Parisini Graeci in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris: Grec 1402 and Grec 1403 respectively. D gives the variant reading Ἐρπεδιτανοι [Erpeditanoi] but in the margin someone has added the regular form Ἐρδινοι [Erdinoi].

Ξ is Barberinus, a codex from the library of Cardinal Francesco Barberini. It is now housed in the Vatican Library

Σ, Φ and Ψ are three manuscripts from the Laurentian Library in Florence: Florentinus Laurentianus 28, 9 : Florentinus Laurentianus 28, 38 : Florentinus Laurentianus 28, 42.

M is the Editio Argentinensis, which was based on Jacopo d’Angelo’s Latin translation of Ptolemy (1406) and the work of Pico della Mirandola. Many other hands also worked on it—Martin Waldseemüller, Matthias Ringmann, Jacob Eszler and Georg Übel—before it was finally published by Johann Schott in Straßburg in 1513. Argentinensis refers to Straßburg’s ancient Celtic name of Argentorate.

N refers to a pair of Latin manuscripts discovered by the Prussian geographer Konrad Mannert.

V is an edition of Ptolemy’s Geography published in Ulm in 1482 by Lienhart Holle, with the assistance of the cartographer Nicolaus Germanus Donis.

X is Vaticanus Graecus 191, which dates from about 1296. It is believed that this manuscript preserves a very ancient tradition. Ptolemy’s description of Ireland is on folia 138v–139r.

4803 and 4805 are two of the Codices Parisini Latini in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris. They are Latin translations of Ptolemy’s Geography by Jacopo d’Angelo: Latin 4803 and Latin 4805.

Erdinoi or Erpeditanoi

The distinction between Ἐρπεδιτανοι [Erpeditanoi] and Ἑρπεδιτανοι [Herpeditanoi] can be easily explained as a simple typographical error: somewhere along the line of transmission, a Byzantine scribe inserted the sign for rough breathing in place of that for smooth breathing. As the diacritic for rough breathing is only found in two manuscripts, while the remaining fifty or so indicate smooth breathing, the former can be safely dismissed.

But we cannot so easily dispose of the other variant reading: Ἐρπεδιτανοι [Erpeditanoi]. This is clearly not a simple typographical error, but a deliberate editorial choice. On this subject, Müller made the following comment:

Two forms of the same name can be seen to lie behind these [variants]. Just as Leptinus and Leptitanus are formed from Leptis, so one could say either Ἐρδίνοι [Erdinoi] and Ἐρδιτανοί [Erditanoi] or Ἐρπεδῖνοι [Erpedinoi] and Ἐρπεδιτάνοι [Erpeditanoi], but surely not Ἐρδίνοι [Erdinoi] and Ἐρπεδιτάνοι [Erpeditanoi]. By a similar confusion in Ptolemy’s Geography (4:1), in the adjoining territories of Mauretania Tingitana and Mauretania Caesariensis, the town of Ἑρπις [Herpis] is noted, while the inhabitants of this region are called (4:2) the Ἑρπεδιτανοι [Herpeditanoi], as though the name of the town were Ἑρπεδίς [Herpedis]. It stands to reason that the neighbours of the Venniknioi would have dwelt by the large river Erne, the ancient name of which may have been Ἐρνος [Ernos] or Ἐρνις [Ernis]; I suspect its natives were called not the Ἐρδινοι [Erdinoi] but rather the Ἐρναιοι [Ernaioi]. (Müller 77)

Goddard Orpen, writing about a decade after Müller, also suspected a possible connection between the name of the people and the name of the river:

Of the tribes on the west coast the Ἐρδȋνοι [Erdinoi] appear to be placed in the district watered by the river Erne. Of this district the “Four Masters,” A.M. 3751, record “a battle against the Ernai of the Firbolg on the plain where Loch Erne now is. After the battle was gained from them the lake flowed over them, so that it was from them the lake is named, i.e. the lake over the Ernai.” Other forms of the name are Ernaigh and Ernaidhe. This suggests the correction *Ἐρνιδοι for the reading in the text, or the supposition of some such derived forms as Ἐρδνᾰδοι [Erdnadoi] or as Ἐρδναȋοι [Erdnaioi]. To this identification it may be objected that Ernai is only a later form of Ivernji or Ἰουέρνȋα [Ivernia] (Ir or Er = Iver or Ever), and that the two forms could not be contemporary. The Erna of Loch Erne are, however, expressly distinguished by Irish genealogists from the Erna of Munster (the former having a Firbolgian, and the latter a Heremoniun descent, ascribed to them), and the similarity of name may be only a coincidence. It may also be remarked that the text of Ptolemy, as it has come down to us, does not always appear to be consistent in the forms adopted. Thus in this very map we have the intermediate form ἴερνος [iernos] as a river name. (Orpen 118-119)

Some earlier researchers had already suggested a link between Ptolemy’s Erdinoi and the River Erne (Ware & Harris 40, O’Flaherty 23-24, O’Conor 172-173).

William Baxter and his disciple Walter Harris suggested that the ethnonym might denote Erigenae Montium, or Mountain Irish (Baxter 122, Ware & Harris 40), while William Beauford pushed his pet theory of Gothic immigrants (Beauford 58-60). I do not have much faith in either of these hypotheses.

The independent researcher Martin Counihan made a strong case for rejecting Ἐρδινοι [Erdinoi] as the more corrupt form:

The name of this group, whose home was at the foot of Donegal Bay, is particularly difficult to interpret. Besides Erpeditani, some editions of the Geography give an alternative version of the name: Erdini. Our first task is to decide which, if either, of these versions is likely to be authentic.

If we look at the names of all the Celtic tribes across Europe, we find that the suffix -dini hardly occurs at all (apart from the possible Erdini, the only other example is the British Votadini) whereas -tani occurs at least a dozen times. For that reason alone, Erpeditani is more probably correct than Erdini.

Moreover, if a name is recorded incorrectly, it seems more likely that syllables are accidentally omitted (“syncope”) than that imaginary syllables are inserted (“epenthesis”). In other words, it is easier to imagine Erpeditani being miscopied as Erdini than vice versa.

These factors suggest rejecting Erdini as erroneous and accepting Erpeditani as the true name of this tribe. However, Erpeditani itself seems rather odd: the ending -ditani, although not completely unprecedented (there was a tribe of Igaeditani in Portugal) looks like a duplication of collective or adjectival suffixes. So, one should consider the possibility that the correct form of the name was neither Erpeditani nor Erdini but something in between: Erpetani, say, or Erpedani. Erpetani and Erpedani are both plausible as Celtic tribal names, and both would mean something like “the Erp-people”, or “Erp’s people”.

So, we can take it as likely that the root of this name was Erp. This spelling, like that of Epdani mentioned earlier, is based on Brittonic or Gaulish pronunciation, the consonant p having been absent in ancient Irish. The authentic Irish form would have been Erc, identical to the personal name Erc which was common in Old Irish. Ptolemy’s Erpeditani were the “people of Erc”.

So common was the name Erc that the Irish genealogical literature records several ancient kindreds based on it, recorded in Old Irish forms such as Húi Erca, Húi Ercain, Húi Meic-Eirc, Cenél Meic-Ercca, Húi Meic-Erce, and Cenél nEircc. The name also occurs numerous times in surviving Ogham stone inscriptions. However, apart from the coincidence of name, there is no good reason to associate any of these families or inscriptions with Ptolemy’s Erpeditani in particular.

As for the origin of the name Erc: it may come from a Proto-Indo-European root (erkw) meaning “glorify” or “shine”. Another possibility, which cannot be ruled out, is that the name is derived from the original Proto-Indo-European word for an oak tree, so that the tribal name once had a meaning which may be loosely translated as “Hearts of Oak”. But, on balance, it is most probable that the name Erc meant “glorious” and the Erpeditani were “Erc’s people”. (Counihan 12-13)

As usual, the contributors to the website Roman Era Names have gone their own way:

Ερδινοι (or Ερπεδιτανοι) (Erdinoi 2,2,5) seem to have lived in the north-west, in Donegal, which is fairly mountainous. The name came from PIE *erədh- ‘high’, whose descendants include OI ard ‘high’. The variant spelling Ερπεδιτανοι [Erpeditanoi] was presumably influenced by Latin pedito ‘to go on foot’ or πεδητης [pedētēs] ‘one who fetters, a hinderer’, but also possibly by πεδιας [pedias] ‘flat, of the plain’. (Roman Era Names)

The only thing that all these scholars have in common is their unquestioned assumption that whatever its true meaning or etymology, this ethnonym is certainly of Indo-European origin.

Conclusions

Assuming that any similarity between Ptolemy’s Erdinoi (or whatever the correct form was) and the historical name Ernai is coincidental, the Erdinoi cannot be identified confidently with any historical tribes. T F O’Rahilly did not even bother to discuss them in his analysis of Ptolemy’s geography of Ireland. Furthermore, the correct form of this ethnonym and its etymology are still matters of scholarly debate.

References

- William Baxter, Glossarium Antiquitatum Britannicarum, sive Syllabus Etymologicus Antiquitatum Veteris Britanniae atque Iberniae temporibus Romanorum, Second Edition, London (1733)

- William Beauford, Letter from Mr. William Beauford, A.B. to the Rev. George Graydon, LL.B. Secretary to the Committee of Antiquities, Royal Irish Academy, The Transactions of the Royal Irish Academy, Volume 3, pp 51-73, Royal Irish Academy, Dublin (1789)

- Martin Counihan, Researchgate (2019)

- Amalia E Gnanadesikan, The Writing Revolution: Cuneiform to the Internet, Blackwell Publishing, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, Chichester (2009)

- Karl Wilhelm Ludwig Müller (editor & translator), Klaudiou Ptolemaiou Geographike Hyphegesis (Claudii Ptolemæi Geographia), Volume 1, Alfredo Firmin Didot, Paris (1883)

- Karl Friedrich August Nobbe, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographia, Volume 1, Karl Tauchnitz, Leipzig (1845)

- Karl Friedrich August Nobbe, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographia, Volume 2, Karl Tauchnitz, Leipzig (1845)

- Charles O’Conor, Dissertations on the History of Ireland to which is subjoined a Dissertation on the Irish Colonies Established in Britain with Some Remarks on Mr Mac Pherson’s Translation of Fingal and Temora, George Faulkner, Dublin (1766)

- John O’Donovan (editor & translator), Annals of the Kingdom of Ireland by the Four Masters, Second Edition, Volume 1, Hodges, Smith, and Co, Dublin (1856)

- Roderic O’Flaherty, James Hely (translator), Ogygia, Or, A Chronological Account of Irish Events, Volume 1, W McKenzie, Dublin (1793)

- Thomas F O’Rahilly, Early Irish History and Mythology, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, Dublin (1946, 1984)

- Goddard H Orpen, Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland, The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Volume 4 (Fifth Series), Volume 24 (Consecutive Series), pp 115-128, Dublin (1894)

- Claudius Ptolemaeus, Geography, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vat Gr 191, fol 127-172 (Ireland: 138v–139r)

- James Ware, Walter Harris (editor), The Whole Works of Sir James Ware, Volume 2, Walter Harris, Dublin (1745)

- Friedrich Wilhelm Wilberg, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographiae, Libri Octo: Graece et Latine ad Codicum Manu Scriptorum Fidem Edidit Frid. Guil. Wilberg, Essendiae Sumptibus et Typis G.D. Baedeker, Essen (1838)

Image Credits

- Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland: Wikimedia Commons, Nicholaus Germanus (cartographer), Public Domain

- Greek Letters: Wikimedia Commons, Future Perfect at Sunrise (artist), Public Domain

- Goddard H Orpen: © Royal Society of Antiquaries Ireland, Fair Use

- Lower Lough Erne: © Falcon, Creative Commons License

- Donegal Bay: © Phil Sangwell, Creative Commons License

- Glengesh Valley, County Donegal: Copyright Unknown, Fair Use

a great history writing bro..hope you okay.