Ἰουερνοι

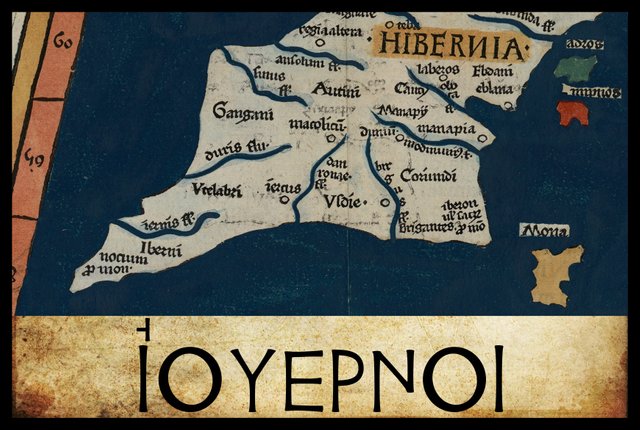

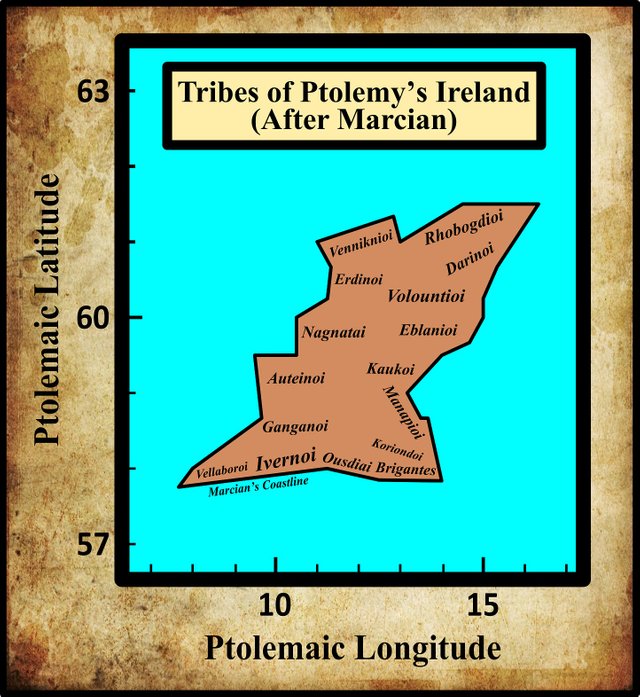

In his description of Ireland, Geography 2:2 §§ 1-10, Claudius Ptolemy records the names and disposition of sixteen Irish tribes. Resuming our voyage around the island, the fifteenth tribe we encounter are the Ivernoi (Latin: Iverni, Hiberni). Ptolemy places these people to the east of the Vellaboroi, who occupy the extreme southwest of the island. Clearly, they are to be associated with the “city” of Ἰουερνις [Ivernis], which Ptolemy locates close to the midpoint of the southern coast.

In his 1883 edition of the Geography, Karl Müller notes five variant readings of this ethnonym. One of these differs from his critical form only in its application of the Greek accents. As the use of these accents was not regularized until the Byzantine era, they are generally considered to be “without authority” (O’Rahilly 1 fn 2, Gnanadesikan 220-221). In his 1838 edition of the Geography, Friedrich Wilberg makes note of two of Müller’s variants, though his critical choice differs from Müller’s. In his edition of 1845, Karl Nobbe agrees with Wilberg’s choice of the critical form.

| Source | Greek | English |

|---|---|---|

| Arg | Ἰουερνοι | Ivernoi |

| Most MSS, B, E | Ἰουερνιοι | Ivernioi |

| X | Ἰουβερνοι | Ioubernoi |

| L2 | Ἰουτερνιοι | Iouternioi |

| A, C, D, L, M, O, P, R, V, W, Δ, Ξ, Π, α, Edd | Οὐτερνοι | Outernoi |

| Source | Latin |

|---|---|

| 4803 | Hiberni |

In Latin translations of the Geography, the Ivernoi are given a variety of names:

- Iverni

- Hiberni

- Iberni

- Iberi

- Uterini

- Outerini

- Iuërni

- Juërni

Arg is the Editio Argentinensis, which was based on Jacopo d’Angelo’s Latin translation of Ptolemy (1406) and the work of Pico della Mirandola. Many other hands also worked on it—Martin Waldseemüller, Matthias Ringmann, Jacob Eszler and Georg Übel—before it was finally published by Johann Schott in Straßburg in 1513. Argentinensis refers to Straßburg’s ancient Celtic name of Argentorate.

A is one of the Codices Parisini Graeci in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris: Grec 1401.

B is one of the Codices Parisini Graeci in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris: Grec 1404.

C is Parisiensis Supplem 119. Presumably this is one of the Codices Parisini Graeci in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris, though I have not been able to confirm this.

D is another of the Codices Parisini Graeci in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris: Grec 1402.

E is another of the Codices Parisini Graeci in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris: Grec 1403.

L is a manuscript from the library at Vatopedi, the ancient monastery on Mount Athos in Greece.

L2 I do not know what manuscript this refers to. Müller makes a distinction between L and L2, but he never clarifies what this distinction entails.

M is Vindobonensis 1, a codex in the Austrian National Library in Vienna.

O is Oxoniensis Seldanus 2, 45, one of the Selden Manuscripts in the Bodleian Library at Oxford.

P and R are Venetian manuscripts identified by Müller as Venetus 383 and Venetus 516. They are possibly kept in the Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana, though I have not been able to confirm this.

V and W are two manuscripts in the Vatican Library, Vaticanus Graecus 177 and Vaticanus Graecus 178.

X is Vaticanus Graecus 191, which dates from about 1296. It is believed that this manuscript preserves a very ancient tradition, though its reading of this ethnonym, Ἰουβερνοι [Ioubernoi], is rejected by most scholars as corrupt. Ptolemy’s description of Ireland is on folia 138v–139r.

Δ is Florentinus Abbatiae 2380, a codex from the Abbey of St Lawrence in Florence.

Ξ is Barberinus, a codex from the library of Cardinal Francesco Barberini. It is now housed in the Vatican Library

Π This manuscript of Ptolemy’s Geography was formerly in the Library of St Gregory on the Caelian Hill in Rome. In 1872 the government of the recently established Kingdom of Italy confiscated the contents of the library, which were subsequently dispersed. Many of the volumes were expropriated by the Vittorio Emanuele II National Library of Rome.

α is identified by Müller as the Codex Ingolstadiensis. He refers to it as the Editio princeps, a term generally reserved for the first printed edition of a work. Today, the editio princeps is usually credited to Desiderius Erasmus, whose complete Greek edition—based on a manuscript provided by Theobald Fettich of Kaiserslautern—was published by Hieronymus Froben in Basel in 1533. Earlier in the same year, however, Peter Apian of Ingolstadt published an incomplete version of the Geography in Greek and Latin. I can only assume that Müller’s Cod α is a copy of this work.

Edd are printed editions of Desiderius Erasmus’s editio princeps of 1533.

4803 is one of the Codices Parisini Latini in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris. It is a Latin translation of Ptolemy’s Geography by Jacopo d’Angelo: Latin 4803.

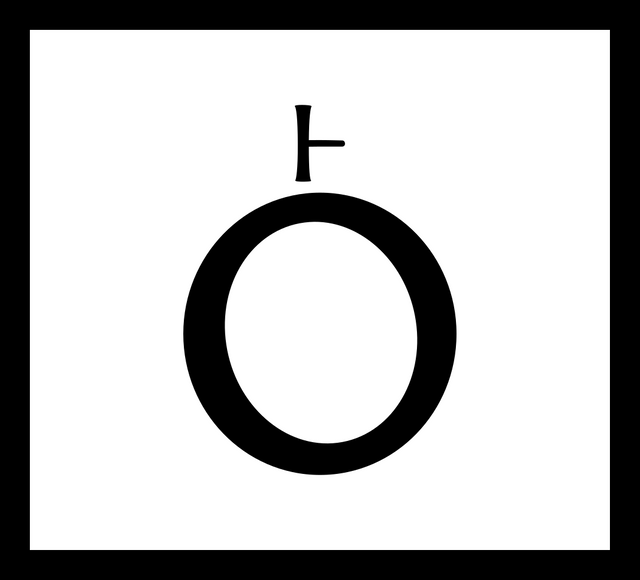

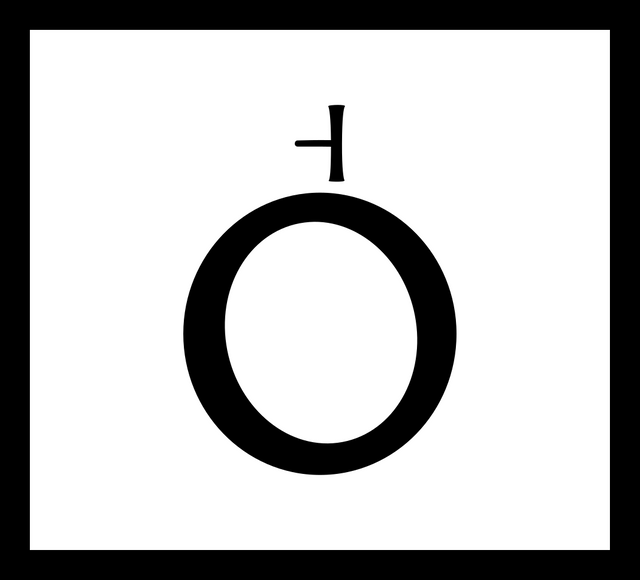

A Note on Ptolemy’s Use of Breathings

In Celtic, v was pronounced like our modern semivowel [w], as it was in Classical Latin. In later forms of Irish, [v] and [w] are found, depending on the context and the dialect. As we have seen several times before in this series, Ptolemy used the Greek digraph ου [ou] to represent the Celtic letter v because the Greek letter digamma, which had formerly represented this sound, had fallen out of use (except as the numeral 6). T F O’Rahilly explained this practice in his Early Irish History and Mythology in connection with the Greek names for Ireland:

The name ’Ιέρνη, “Ireland”, had probably been picked up by the Massaliot Greeks, from merchants and from their Celtic neighbours, as early as the fifth century B.C. ... The digamma had disappeared from Ionic as early as the seventh century B.C.; and when Massaliot Greeks first heard the name Īvernā [Ireland], they presumably had no means of indicating the -v- and simply dropped it. Later the Greeks adopted the expedient of representing v in foreign names by ου ... We may take it that Pytheas [believed by O’Rahilly to be Ptolemy’s principal source for information about Ireland] retained the traditional name ’Ιέρνη ... whereas in dealing with other names previously unrecorded, we find him representing Celtic v by Greek ου, as for instance in ... Bouvinda [Βουουινδα] ... Ptolemy, or some near predecessor of his, modernized ’Ιέρνη into ’Ιουερνία [Ivernia] ... (O’Rahilly 41-42)

Once again I quote Amalia Gnanadesikan, the Technical Director for Language Analysis at the University of Maryland’s Center for Advanced Study of Language, on the use of diacritics in ancient Greek. In her book The Writing Revolution, she makes the following pertinent comment on the question of smooth and rough breathing in Ptolemy’s Alexandria:

In the process of accumulating and copying texts, the Alexandrian scholars began to show concern for matters of orthography. They found that at certain points the lack of a written form of [h] made for ambiguity. They noted that the Greeks living in Italy had been more free-thinking than the Athenians. While they had gone along with the adoption of the Ionic alphabet, they continued to write [h] by cutting the hēta in half and using ├. The Alexandrians adopted the Italian Greeks’ half H, but wrote it as a superscript on the following vowel, so that, for example,

was ho. Loving symmetry, they made the other half of H stand for the lack of an [h] sound before a vowel:

These diacritics came to be termed “rough breathing” (for [h]) and “smooth breathing” (for lack of [h]). Their use was for many centuries largely reserved for cases where ambiguity could arise without them. These marks later became ‘ and ’, so that ὁ was ho and ὀ plain o ... Only by the ninth century AD (well into the Byzantine period, AD 330–1453) did the use of breathing and accent diacritics become fully regular, with all vowel-initial words marked for “rough” or “smooth” breathing and all words marked for accent. (Gnanadesikan 220 ... 221)

I take these remarks to imply that Ptolemy probably only employed the diacritics for smooth and rough breathings in cases where the correct reading was not already obvious to the reader. In other words, he probably did not include the breathing in common Greek words, as its presence in such words was too well known to require inclusion. In the case of foreign toponyms and ethnonyms, however, he probably did include it. Hence we have Ἰουερνις rather than Ιουερνις.

Critical Reading

Müller chose Ἰουερνοι [Ivernoi] as the critical form even though it only occurs in a single source—Arg—which is not even a manuscript. Wilberg and Nobbe’s choice, Ἰουερνιοι [Ivernioi], is the commonest reading. The remaining variants can be quickly dismissed:

Ἰουβερνοι [Ioubernoi]: This variant probably arose due to the influence of the common Latin name for this tribe, Hiberni. Ptolemy’s use of the digraph -ου- [-ou-] to represent the Celtic semivowel v (pronounced [w]) suggests that the following letter was a vowel, not a consonant. Curiously, this variant occurs in Vaticanus Graecus 191, which dates from about 1296. This Byzantine manuscript is thought to preserve a very ancient tradition of Ptolemy’s Geography, but in this case it appears to have been contaminated by Latin.

Ἰουτερνιοι [Iouternioi]: This variant can be dismissed for the same reason as the preceding reading. The presence of the -τ- [-t-] may be related to the following variant.

Οὐτερνοι [Outernoi]: Likewise, this variant can be dismissed for the same reason as the two preceding readings. This reading, however, is quite common. It occurs in at least thirteen manuscripts. It was also chosen as the critical form in the earliest printed editions of the Geography, those of Peter Apian (1533) and Desiderius Erasmus (1533). I cannot account for the presence of the -τ- [-t-]. It is probably related to the preceding variant, though which came first I cannot say.

But which of the two critical choices is the correct form: Müller’s Ἰουερνοι [Ivernoi] or Wilberg & Nobbe’s Ἰουερνιοι [Ivernioi]? The latter is by far the commoner reading, but the former is preferable on linguistic grounds, as we shall see below. Müller chose the former, it seems, because that is the reading in Stephanus of Byzantium. Müller even reproduces the accents used by Stephanus (Müller 78).

Stephanus of Byzantium

Ptolemy’s Ivernis, the “capital city” of the Ivernoi, is mentioned by Stephanus of Byzantium, a geographer who flourished in the 6th century CE. His Ethnica, an alphabetic gazetteer of ethnographic terms, survives only in scattered fragments and an abridged epitome by an otherwise unknown scholar Hermolaus. Under the letter iota, we find the following entry:

Ivernē [Ἰουέρνη], a city among the Pretanians. The people: Ivernoi [Ἰούερνοι] (Stephanus Byzantius 335)

It is probably safe to assume that a corrupt copy or epitome of Ptolemy’s Geography was Stephanus’s source for this entry and its presence does not imply that Ivernis was still in existence in the 6th century. By then the descendants of Ptolemy’s Ivernoi were known by their Irish name Érainn (see below), so Stephanus’s Ivernoi is anachronistic. Nevertheless, he does transmit an early reading of this ethnonym, and one which is probably the correct reading, even though it appears in only a single surviving manuscript of the Geography.

O’Rahilly

In his Early Irish History and Mythology, T F O’Rahilly had the following to say about this ethnonym:

Iverni. Their name has survived as Érainn, which goes back to a variant form *Ēvernī. Ptolemy’s Iverni were situated approximately in what is now Co. Cork, just as the name Érainn is applied chiefly to the Érainn of Co. Cork ... The Corcu Loígde are the historical representatives of Ptolemy’s Iverni. (O’Rahilly 9 ... 7 fn 3)

Elsewhere, O’Rahilly identifies the Érainn as the second of the four principal Celtic groups that colonized Ireland (Stephanus’s Pretanians derives from the name of the first group, the Priteni). They were also known as the Builg and are to be identified with the Belgae Celts of the classical writers and the Fir Bolg of Irish legend:

The Builg, commonly called Fir Bolg, and also known as Érainn (Iverni). Their name (*Bolgī) identifies them with the Belgae of the Continent and Britain. According to Irish tradition they were of the same stock as the Britons; and their own invasion-legend tells how their ancestor Lugaid came from Britain and conquered Ireland ... The fact that Bolga appears as another name of Ailill Érann in the pedigree of the Érainn, taken in conjunction with the further fact that Bolg was one of the mythical ancestors of the Corcu Loígde (the foremost representatives of the Érainn), is sufficient proof, without entering into further arguments, that Builg (Fir Bolg) and Érainn were two names for the one people. The only point of difference between the names was that Érainn (like Ptolemy’s Iverni) was applied especially to those Builg who dwelt in the south of Ireland. (O’Rahilly 16 ... 54)

As O’Rahilly also points out, the identification of the Fir Bolg with the Belgae Celts was nothing new. As early as 1685, the Irish historian Roderic O’Flaherty had made the connection in his Ogygia (O’Flaherty 21).

In O’Rahilly’s model, the Érainn invaded Ireland from Britain “within the sixth-fourth centuries [BCE]” (O’Rahilly 84). In the Short Chronology, which I espouse, it was the Érainn who first cleared the forests of Ireland and began to till the soil. They were also responsible for the construction of the earliest megalithic monuments. Their archaeology has been grossly misdated by modern academia and attributed to fictitious Neolithic farmers of about 4500-2500 BCE.

In another work from 1946, O’Rahilly carried out an etymological investigation of the Irish ethnonym Érainn and the related Irish toponym Ériu [Ireland]. It is too long to quote in full and the argument is quite elaborate. In brief, however:

Just as the Celts employed the names or epithets of deities as personal names, so it was common practice with them to employ pluralized forms of these names or epithets as tribal names. Hence there is prima facie reason to suppose that the *Ēvernī or Érainn got their name from a god *Ēvernos or a goddess *Ēvernā, or from both jointly. (O’Rahilly, Ériu 21)

After presenting supporting evidence, he then turns to the etymology of Ériu and Érainn:

There remains the question of the etymology of the names we have been discussing. For practical purposes these may be narrowed down to two: *Ēveriū and *Ēvernā, each of which has a by-form with Ī- for Ē-. As these two names not only resemble each other in form but also coincide in meaning, it is unnecessary to argue that they are closely related. (O’Rahilly, Ériu 23)

O’Rahilly then argues that the by-forms with Ī- were the original forms:

The evidence strongly suggests that the forms with ī- were those employed by the pre-Goidelic inhabitants of Ireland and by the Britons, while the forms with ē- were exclusively Goidelic ... In *Ēvernā, *Ēvernos, we doubtless have the Celtic suffix -erno- ... Likewise the -eri(j)ū of *Ēveriū may be taken as a suffix ... We thus arrive at ēv or īv as the basic element in the two names. Celt. ē goes back to IE. ei; Celt. ī to IE. ī or ē. But there is, I suggest, a third source for Celt. ī, namely, IE. ēi ... Accordingly I take it that ... īv- represents IE. ēiṷ- ... readily referred to the well-known IE. root ei- implying motion ... The goddess-names *Ēvernā, *Ēveriū, would thus mean ‘she who travels regularly, she who moves in a customary course’, from which we infer that the goddess so designated was the sun-goddess, for the sun was the great celestial Traveller, whose regular motions exemplified the divine law and order of the universe. (O’Rahilly, Ériu 24-)

O’Rahilly rounds off this elaborate argument with a mythical flourish:

Celtic belief tended to locate the Otherworld, where the Sun-god and his consort reigned, in one or more islands in the western ocean. Of all known lands Ireland lay nearest to the setting sun; hence it seems fitting that our western island should have been called by a name which emphasized the solar aspect of the terrestrial goddess. Worth noting, perhaps, in this connexion is one of the traditional Irish explanations of Hibernia, viz. ‘the island of the setting sun’. (O’Rahilly, Ériu 27-28)

This etymology has not found much favour with other scholars. It does, however, explain how the Belgae who settled in Ireland came to acquire a new name, one that their cousins on the Continent and in Britain did not share.

Roman Era Names

The contributors to the website Roman Era Names have emended the smooth breathing of most manuscripts to a rough breathing, giving Huwernoi or Hubernoi as the critical form:

Ἱουερνοι(Ἱουβερνοι) (Huwernoi or Hubernoi 2,2,7) lived in the south, around Cork. Latin hibernus ‘belonging to winter’, possibly from PIE *ghei- ‘snow, winter’, would suit this area, with its mild climate due to the Gulf Stream. This might have made it suitable for early traders from the Mediterranean to over-winter, though they might also have considered that high rainfall made that area winter all year! Ibernio, at Iwerne in Dorset, is a parallel, from Latin hiberno ‘to occupy winter quarters’.

If this winter logic is correct, the classical name Hibernia originally meant the south of Ireland before being generalised to the whole island. Isaac (2009) discussed early names for Ireland and suggested that PIE *auer- ‘to flow’ led to early Celtic *eiweryon ‘upon the water’ (hence ‘at the edge of the world’), from which Greek-style loss of W led to Irish forms such as modern Éire, whereas Latin viridis ‘green’ (of uncertain deep etymology) led to Welsh gwyrdd which allowed reinterpretation into Ywerdon ‘the greenery’. (Roman Era Names)

In my opinion, this winter logic is the false etymology that Latin scholars imposed upon a Celtic name whose true etymology was a mystery to them. I am, of course, not the first to suggest this:

The Greek name for Ireland is Iernē, which in some late writers (e.g. Ptolemy) becomes Ivernia. The best known Latin name of Ireland, Hibernia, employed by Caesar, Pliny, and Tacitus, is a modification of Ivernia under the influence of hībernus, ‘wintry’. (O’Rahilly, ¬¬Ériu 7)

As for the readings Huwernoi and Hubernoi, what, one might ask, has happened to Ptolemy’s initial Ι? Can one simply drop it as an inconvenience?

Martin Counihan

The independent researcher Martin Counihan has much to say about this Ptolemaic ethnonym:

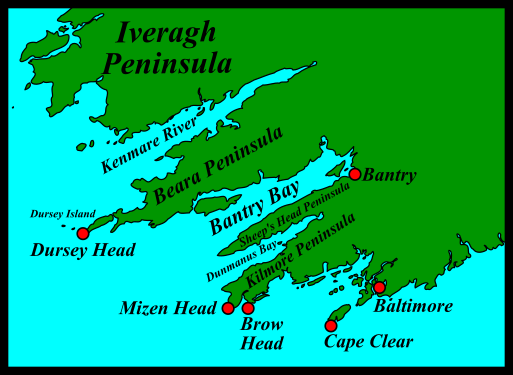

The Iverni were on the south coast in the region of County Cork and south Kerry, where Ptolemy recorded also an estuary called Iernus, now Kenmare Bay, and a town called Ivernis or alternatively Iernis. Later, in Old Irish, the tribe came to be called the Érainn and the estuary Inber Erannan.

If Iverni and Érainn are essentially the same name, why do they appear so different? A possible explanation is that the tribe’s original name in Archaic Irish was very similar to Iverni, and as such it was picked up by voyagers from the Continent during the early Iron Age and transmitted to the Mediterranean world, giving rise eventually to the Latin Iverni and later, as the name of the whole island, Ivernia and later still Hibernia. But in Ireland, meanwhile, the first syllable came to be elided, leaving a name like Erni which developed into the Old Irish Érainn. It might seem surprising that these south-coast Irish dropped the first bit of their name, but this process—known to linguists as apheresis—does happen from time to time in the evolution of names. It is very common in personal names (Sandra from Alexandria) and can be found occasionally in city-names (Zaragoza from Caesar Augusta) and territory-names (Tuscany from the Etruscans). The apheresis leading to Érainn may have been helped by the fact that Érainn by itself would not have been meaningless: in Old Irish, ér is an adjective meaning “great” or “noble”, so Érainn may have seemed to mean that the people were the descendants of a noble ancestor. (Counihan 8)

Here, Counihan proposes a novel explanation of how Iverni gave rise to the Irish Érainn. O’Rahilly believes that this is adequately explained by the usual rules which governed the phonological changes that occurred as Proto-Indo-European evolved into Proto-Celtic and Old Irish.

This explanation of how Iverni was reduced to Érainn is given some support by the fact that the name of the estuary appears not as Ivernus but as Iernus, as if the process of elision was already under way when the Geography was being compiled. (Counihan 8)

O’Rahilly believes that Ivernus became _Iernus because the early Greeks, having no way of representing the Celtic letter -v- (pronounced [w]), simply dropped it. Later, Ptolemy or some other scholar adopted the expedient of representing this sound by the Greek digraph -ου- [-ou-] (O’Rahilly 41-42, 41 fn 2).

And a little more evidence can be gleaned from the ocean to the south of Ireland: editions of the Geography record it as the Oceanus Vergivius or Verginius. As it stands this is a mysterious-looking name with no evident meaning, but if we take the second variant and suppose that the second syllable is an erroneous insertion, it reveals Vernius as the possibly-authentic form of the name. This could come from Ivernis with loss of the initial letter. So, a close reading of Ptolemy’s data suggests that an initial tribal name like Iverni could have been undergoing apheresis during the centuries when Ptolemy’s data was being collated, leading ultimately to the Old Irish Érainn. (Counihan 8-9)

This is very interesting. I intend to take a closer look at the names Ptolemy gives to the seas around Ireland in a later article in this series. Here I will merely say that Counihan’s hypothesis that the ethnonym underwent apheresis would begin to look more attractive if the correct name of the ocean was indeed Vernius.

There remains the question of the original meaning of the hypothetical archaic name Iverni. Some help comes from the fact that it occurred not only in Ireland but also in England, because in north Dorset there is a river Iwerne, on which there are the villages of Iwerne Minster, Iwerne Courtney and Steepleton Iwerne. In 1936 the Swedish scholar Eilert Ekwall published a dictionary of English place-names which became the standard academic reference on the subject, and which is still an essential resource for place-name specialists in England. Ekwall was in no doubt that the name Iwerne for the Dorset river is identical to the Latin Ivernos for Kenmare Bay and that the root of both names is an ancient word for the yew tree.

For Iwerne, it is interesting that the Domesday Book included variant spellings Werne and Euneminstre (for Iwerne Minster), illustrating that there was a tendency for apheresis of the Dorset name even though it eventually survived intact to the present day. If the first syllable was nearly lost in England, it makes it all the more plausible that it was lost in Ireland.

A word for “yew” in Old Irish is eó, but names recorded in the Ogham script of stone inscriptions tell us that in earlier Archaic Irish it took the form ivo, which (probably with collective and diminutive suffixes, and as a plural) gave Ptolemy’s Iverni, which may be translated “people of the yew-grove”. This does not mean that yews were especially plentiful in the territory of the Iverni, nor that they necessarily made much practical use of the tree; rather, the yew had a sacred and cosmological significance. The tree seems immortal, but the foliage brings death.

In medieval times, the region of south-coast Ireland which had been the territory of the Iverni/Érainn came to be dominated by a new dynasty, the Eóghanachta, who considered themselves to be the descendants of an eponymous leader, Eóghan Mór (Owen the Great). It is not clear whether he was a real person, in which case he may have been a contemporary of Ptolemy of Alexandria, or whether he was a purely mythological figure. Eó being the yew, Eóghan means “yew-born”, continuing the tradition which had given the Iverni their name in the far distant past. (Counihan 8-9)

Who knows? This could be the correct explanation. I certainly find it more convincing than the “wintry” logic of Roman Era Names.

Earlier Scholarship

In the 16th century, the English antiquary William Camden placed the Ivernoi in Desmond, or South Munster:

[Desmond] was formerly peopled by the Velabri, and the Iberni, who in some Copies are call’d Uterini ... I am as much at a loss for the People which Ptolemy places upon these Promontories [ie the long peninsulas in the southwest of Ireland]; seeing their name differs in several Copies, Iberni, Outerini, Iberi, Iverni; unless perhaps they are a Colony of the Iberi in Spain, as well as their neighbours the Luceni and Conconi. (Camden 1335 ... 1336)

Writing in the 17th century, the Irish scholar James Ware followed Camden, almost copying him word for word:

Uterini, a People so called. Or, (according to a variety of Copies) Iberni, Iberi and Iuërni, inhabited the more Southern Parts of Desmond. Perhaps they were a Colony of the Iberians. One may venture to make this Conjecture from their Name and Situation, which is opposite to the Spanish Coast. (Ware & Harris 45)

Ware’s 18th-century editor Walter Harris had nothing to add to this—for once.

In the 18th century, the Welsh scholar William Baxter suggested that Ivernoi was related to the names of two other Irish tribes recorded by Ptolemy, the Auteiroi (Auteinoi is thought to be the correct form) and the Erdinoi. Baxter offered the following possible etymology:

Auteiri ... I am inclined to believe them to have been Erigenas [Irish-born], or Autochthonous Iberni ... for in ancient Britain Er stood for Terra [Land] ... whence the native Irish are called Erion, or Erii by the Brigantians: and the island itself Iris by the Greeks, as though it were named Eriorum Insula [Island of the Erii]

Erdini ... Eri dineu, or Erigenæ montium [Irish-born of the mountains]

Iberni: In some books of Ptolemy they are called corruptly Ὄυτερνοι [Outernoi], unless the two be considered synonymous ... These were a people of Ireland, in the extreme parts of Munster, where the river Ibernus flowed. They were so called, it seems, by the Britons, after a good part of Ireland was occupied by colonies of the Brigantes and the Belgae. (Baxter 30 ... 122 ... 134)

The interesting thing about this is that Baxter has correctly identified the linguistic connection between Ptolemy’s Ivernoi and the historical Érainn (Erion or Erii). He has also correctly identified the Érainn as descended from British colonists of Belgic stock. O’Rahilly would have been proud. As for his claim that the name goes back to a Celtic word er, meaning land, this still has some adherents today. O’Rahilly mentions it in the article in Ériu which I quoted from above, though he believes the etymology evolved in the opposite direction:

On the other hand, we may safely equate O. Ir. íriu, gen. írenn, ‘land’, with *Īverijū, W. Iwerddon; originally a doublet of Ériu, ‘Ireland’, íriu acquired the general sense of ‘land, ground’, just as *Albijū ‘Britain’ (O. Ir. Albu, id.), has in Welsh (elfydd) acquired the sense of ‘land’. (O’Rahilly, Ériu 10)

In 1753, the Irish antiquary Charles O’Conor brought out his Dissertations on the History of Ireland, a work in which we find yet another etymology of Ptolemy’s ethnonym Ivernoi:

The two Southern Provinces took the Name of Mumha [Munster], from Eochadh Mumha, King of Ireland several Ages before the Incarnation [of Christ]. It was inhabited by the South Iberians, (by Ptolomey named Juverni) who took their Name from Eber-Finn, the eldest Son of Golamh of Spain, the common Father of the Milesian Race. (O’Conor 176-177)

Needless to say, this is fanciful and impossible to accept. The Ireland Ptolemy describes is pre-Milesian (ie pre-Goidelic), as O’Rahilly has shown (O’Rahilly 39-42).

In the late 18th century, the Irish scholar William Beauford linked Ivernoi with Iveragh, one of the prominent peninsulas in the south-west of Ireland:

Ουτερνοι [Outernoi], Pal. Ιουερνιοι [Ivernioi], Ware thinks them the inhabitants of Desmond. They being denominated Iberni, Iberi, and Juërni, were most probably the Ibh Earagh of the Irish, the ancient inhabitants about Bear Haven, and the southern parts of the count of Kerry, and a part of the southern Ernai. (Beauford 63)

Like Baxter, he has correctly identified the Ivernoi—in part, at least—with the Érainn (Ernai). Bear Haven is a harbour on the southern shore of the Beara Peninsula in County Cork.

In the early 19th century, Fr Charles O’Conor, grandson of the antiquary of the same name cited above, had much to say concerning this Ptolemaic ethnonym:

The Uterini, in other codices Iberni, Iberi and Juerni, inhabited South Desmond. Their origin is indicated by the very name itself. And, indeed, if each of the Irish names used by a Ptolemy are collated with the British names he uses, and then with the Spanish names, we will be compelled to admit that the Spanish are by far the most numerous, and relate to the most ancient of times and so agree with those that were referred to above concerning the earliest expeditions of the Phoenicians to the Sacred Isle. Therefore, it is by no means absurd for Strabo to say of Homer: “Hence the poet, knowing of similar expeditions to the extremities of Iberia, and having heard of its wealth and other excellencies, (which the Phoenicians had made known,) feigned this to be the region of the Blessed, and the Plain of Elysium ... I repeat that the Phoenicians were the discoverers [of these countries], for they possessed the better part of Iberia and Libya before the time of Homer” [Strabo 225 ... 226].

You have seen above in Ptolemy—under the headings Albain, Erin and Iernus—that the word Hibernia [Ireland] means Occidentalis Insula [Western Island], or Ultima Insula [Furthest Island].

O’Conor’s interpretation of Hibernia as Occidental [western, of the setting sun] is very old. In the Book of Invasions we read:

And so Ireland [Hibernia] is called “the island of the west” : Hyberoc in Greek is called occasus [setting, west] in Latin; nia or nyon in Greek is called insula [island] in Latin. (Macalister 165)

Macalister surmises that hyberoc is a corruption of the Greek ἔσπερος [hesperos], which means evening or western, while nyon is a corruption of νῆσον [nēson], island. This etymology, which O’Rahilly refers to as “one of the traditional Irish explanations of Hibernia (Ériu 28) is no longer considered tenable. However, the scholar Whitley Stokes once suggested that the Old Irish name for Ireland, Ériu, could be cognate with the Sanskrit avara, which also means western (Joyce 459).

O’Conor then summons several arcane sources to plead his case that in Phoenician the word Ebrin or Ibrin meant ends, limits and was applied by them to the Iberians, who lived at the ends of the world. O’Conor concludes:

From all of this, and from what was said above under the heading Albain, Iernæ is clearly to be chosen as the origin of the Irish name. The Iberian, Celtic and Phoenician origin of the people is beyond question. (Fr O’Conor lvii-lviii)

At the end of the 19th century, it was the turn of Goddard Orpen to add his contribution to the debate:

A special interest attaches to the identification of Ἰουερνίς [Ivernis] as it was evidently the chief town of the Ἰούερνοι [Ivernoi], the people who gave their name to the island, and who are now generally regarded as the principal representatives of the pre-Celtic or non- Aryan stock in Ireland. This tribe, whose name is connected with the Emher or Ebher = Ever of the Milesian legend, is usually placed in the extreme S. W., but this position is not warranted by Ptolemy’s text, where they are placed on the south coast after the Οὐελλάβοροι [Vellaboroi] with the Οὐσδίαι [Ousdiai] above them and the Βρίγαντες [Brigantes] more to the east, in the S.E. corner, in fact. Besides, they cannot be dissociated from the town Ἰουερνίς. I should suppose that their territory extended along the south coast from Waterford to perhaps Kinsale, and that they were separated from the Οὐσδίαι by the river Suir. (Orpen 122)

Orpen’s assertion that the Érainn were pre-Celtic or non-Aryan was popular in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, but has few adherents today. It was still being espoused by Eoin MacNeill as late as 1920:

Another considerable element of the ancient population was the Iverni, as they were called by Ptolemy in the second century. Ptolemy locates them in the middle of southern Ireland. The Irish form of their name in the time of our most ancient writings was Érainn, more familiar in later usage in the accusative form Érna. They have been sometimes called Erneans in English ... From the Iverni the whole island took the names by which it was known to the ancient Irish, the Britons, the Greeks, the Romans, and therefore no doubt to the Celts in the neighbouring parts of the Continent. But we have seen that the original Iverni, in Irish tradition, were a remnant of the pre-Celtic population. Ireland therefore was named by the Celts, as Britain and Ireland were jointly named, from an older population which the invading Celts found in possession. The Romans changed Iverni into Hiberni, through a process known as popular etymology. Hiberni suggested to them the Latin word meaning “wintry.” (MacNeill 65 ... 66-67)

In the Short chronology, there were no pre-Celtic inhabitants of Ireland or Britain (at least not in post-glacial times). Although MacNeill discusses some possible Celtic etymologies for the Ivernic ethnonym, he dismisses them:

But we have seen that, in Irish tradition, the original Iverni were a pre-Celtic people, and we are under no necessity to discover a Celtic origin for their name. For my part, granted that this people bore the name Iveri, changed afterwards into the adjectival form Iverni, I see no serious difficulty in supposing that this name was a local variant of Iberi, the name by which the people of Spain were known to the ancient Greeks and Romans. (MacNeill 68)

MacNeill’s assertion that the Érainn were a pre-Celtic people “in Irish tradition” is quite unfounded. They were pre-Goidelic (or pre-Milesian, as Irish tradition expresses it), not pre-Celtic. In time, though, our native genealogists created a fake Goidelic pedigree for them (O’Rahilly 77).

Conclusions

Ptolemy’s Ivernoi were undoubtedly the ancestors of the historical Érainn, the predominant Belgic colonists of Ireland. As far as the etymology of their ethnonym is concerned, the debate continues, but there can be little doubt that it is of Celtic origin.

References

- William Baxter, Glossarium Antiquitatum Britannicarum, sive Syllabus Etymologicus Antiquitatum Veteris Britanniae atque Iberniae temporibus Romanorum, Second Edition, London (1733)

- William Beauford, Letter from Mr. William Beauford, A.B. to the Rev. George Graydon, LL.B. Secretary to the Committee of Antiquities, Royal Irish Academy, The Transactions of the Royal Irish Academy, Volume 3, pp 51-73, Royal Irish Academy, Dublin (1789)

- William Camden, Britannia: Or A Chorographical Description of Great Britain and Ireland, Together with the Adjacent Islands, Second Edition, Volume 2, Edmund Gibson, London (1722)

- Martin Counihan, Researchgate (2019)

- Patrick S Dinneen, Foclóir Gaedhilge agus Béarla: An Irish-English Dictionary, Irish Texts Society, M H Gill & Son, Ltd, Dublin (1904)

- Eilert Ekwall, The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Place-Names, Third Edition, Clarendon Press, Oxford (1947)

- Amalia E Gnanadesikan, The Writing Revolution: Cuneiform to the Internet, Blackwell Publishing, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, Chichester (2009)

- G R Isaac, A Note on the Name of Ireland in Irish and Welsh, Ériu, Volume 59, pp 49-55, Royal Irish Academy, Dublin (2009)

- Patrick Weston Joyce, The Origin and History of Irish Names of Places, Volume 2, Phoenix Publishing Co, Ltd, Dublin (1875)

- Charlton T Lewis, Charles Short, A New Latin Dictionary, Harper & Brothers, Publishers, New York (1891)

- Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, Eighth Edition, American Book Company, New York (1901)

- Robert Alexander Stewart Macalister, Lebor Gabála Érenn: The Book of the Taking of Ireland, Part 1, Irish Texts Society, Volume 34, The Educational Company of Ireland, Ltd, Dublin (1938)

- Eoin MacNeill, Phases of Irish History M H Gill & Son, Ltd, Dublin (1920)

- Karl Wilhelm Ludwig Müller (editor & translator), Klaudiou Ptolemaiou Geographike Hyphegesis (Claudii Ptolemæi Geographia), Volume 1, Alfredo Firmin Didot, Paris (1883)

- Karl Friedrich August Nobbe, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographia, Volume 1, Karl Tauchnitz, Leipzig (1845)

- Karl Friedrich August Nobbe, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographia, Volume 2, Karl Tauchnitz, Leipzig (1845)

- Charles O’Conor, Dissertations on the History of Ireland to which is subjoined a Dissertation on the Irish Colonies Established in Britain with Some Remarks on Mr Mac Pherson’s Translation of Fingal and Temora, George Faulkner, Dublin (1766)

- Fr Charles O’Conor, Rerum Hibernicarum Scriptores Veteres, Volume 1, Prolegomena, Pars I, John Seeley, Buckingham (1814)

- Roderic O’Flaherty, James Hely (translator), Ogygia, Or, A Chronological Account of Irish Events, Volume 1, W McKenzie, Dublin (1793)

- T F O’Rahilly, On the Origin of the Names Érainn and Ériu, Ériu, Volume 14, pp 7-28, Royal Irish Academy, Dublin (1946)

- Thomas F O’Rahilly, Early Irish History and Mythology, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, Dublin (1946, 1984)

- Goddard H Orpen, Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland, The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Volume 4 (Fifth Series), Volume 24 (Consecutive Series), pp 115-128, Dublin (1894)

- Claudius Ptolemaeus, Geography, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vat Gr 191, fol 127-172 (Ireland: 138v–139r)

- Stephanus Byzantius, August Meineke (editor), Ethnica, Georg Reimer, Berlin (1849)

- Strabo, Hans Claude Hamilton, William Falconer, The Geography of Strabo, Volume 1, Henry G Bohn, London (1854)

- Rudolf Thurneysen, Osborn Bergin (translator), D A Binchy (translator), A Grammar of Old Irish, Translated from Handbuch des Altirischen (1909), Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, Dublin (1946, 1998)

- James Ware, Walter Harris (editor), The Whole Works of Sir James Ware, Volume 2, Walter Harris, Dublin (1745)

- Friedrich Wilhelm Wilberg, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographiae, Libri Octo: Graece et Latine ad Codicum Manu Scriptorum Fidem Edidit Frid. Guil. Wilberg, Essendiae Sumptibus et Typis G.D. Baedeker, Essen (1838)

Image Credits

- Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland: Wikimedia Commons, Nicholaus Germanus (cartographer), Public Domain

- Greek Letters: Wikimedia Commons, Future Perfect at Sunrise (artist), Public Domain

- T F O’Rahilly: Copyright Unknown, Fair Use

- Lough Leane, Killarney: © Christophe Meneboeuf, Creative Commons License

- Sunset over Bantry Harbour, County Cork: © 2019 Pictorem, Fair Use

- River Iwerne, Dorsetshire, England: © John Palmer, Creative Commons License

- Iwerne Minster, Dorsetshire, England: © Chris Downer, Creative Commons License

- Wedge Tomb, Glantane East, County Cork: © Ceoil, Creative Commons License

An extremely dense publication. A lot of valuable historical information. I greatly appreciate the care you took with each paragraph, with each quote, even with the images. His conclusion is quite emphatic but it must be true: the origin is Celtic. Congratulations on this article that in my opinion should be published in some arbitrated magazine. Have you tried? Congratulations also for the Curie vote because it is a way to encourage you to continue writing about your research and make these interesting posts. Kind greetings @harlotscurse

Thank you for the nice comment. I am happy to publish my findings on Steemit for anyone to access for free. I have no interest in contributing to "peer-reviewed" journals (ie controlled gatekeepers).

Hello! A pleasure ♡

Wooooooooowww that great information friend! This is so splendid and in-depth, a great way to learn new things ♡♡

The study to which the work Geographia by Cláudio Ptolomeo has been submitted is extensive.

The original language and the different versions have been affected to the point of originating an extensive debate over centuries about the Ptolemaic ethnonym for the different tribes.

This research, which you have done provides logical details that lead to the conclusion clearly.

Great job.

damn, you did a real treat! I find it very interesting to study the linguistics of a people and go back to its history to understand its transformations and inheritances. do you do it for work or is it your passion? congratulations on the curie vote

Ancient history is one of my passions. Thanks for the kind words.

Hi harlotscurse,

Visit curiesteem.com or join the Curie Discord community to learn more.