Ῥοβογδιοι

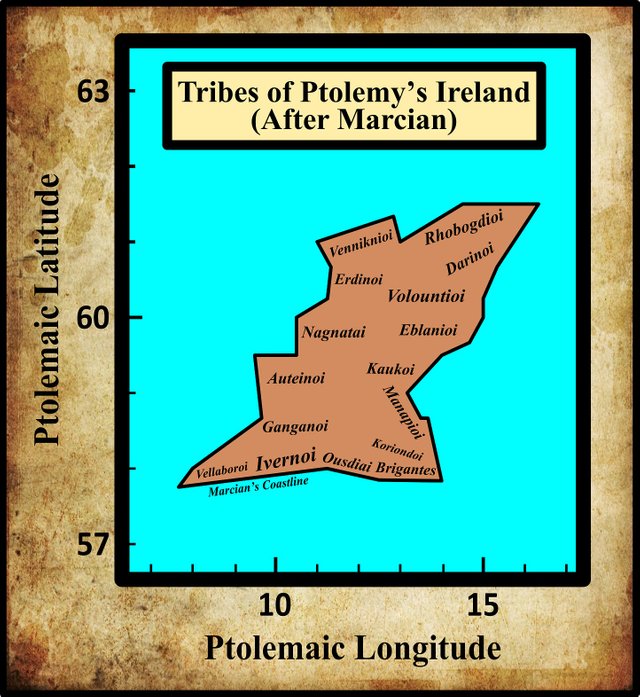

In his description of Ireland, Geography 2:2 §§ 1-10, Claudius Ptolemy records the disposition of sixteen Irish tribes. Beginning, as before, in the southeast corner of the island and proceeding in a counterclockwise direction, the eighth of these are the Rhobogdioi (Latin: Robogdii or Rhobogdii). As these are included among the tribes of the east coast as well as those of the north coast, their territory is in the northeast corner of the island.

In his 1883 edition of Ptolemy’s Geography, Karl Müller noted five variant readings of this ethnonym:

| Source | Greek | English |

|---|---|---|

| Most MSS | Ῥοβογδιοι | Rhobogdioi |

| R | Ῥοβογδοοι | Rhobogdooi |

| O | Ῥοβονδιοι | Rhobondioi |

| L, M, N, O, Δ, ב | Ῥοβουγδιοι | Rhobougdioi |

| C | Ῥογδιοι | Rhogdioi |

| P | Ῥοβογδοι | Rhobogdoi |

In Geography 2:2, Rhobogdioi occurs in the nominative plural. In 2:8, it is given in the accusative plural (governed by μετα [meta], “after”. In the table above, the latter has been transposed into the nominative plural.

C is Parisiensis Supplem 119. Presumably this is one of the Codices Parisini Graeci in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris, though I have not been able to confirm this.

L is a manuscript from the library at Vatopedi, the ancient monastery on Mount Athos in Greece.

M is Vindobonensis 1, a codex in the Austrian National Library in Vienna.

N and O are Oxoniensis Seldanus 2, 46 and Oxoniensis Seldanus 2, 45, two of the Selden Manuscripts in the Bodleian Library at Oxford.

P and R are Venetian manuscripts identified by Müller as Venetus 383 and Venetus 516. They are possibly kept in the Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana, though I have not been able to confirm this.

Δ is Florentinus Abbatiae 2380, a codex from the Abbey of St Lawrence in Florence.

ב is identified by Müller as Scorialensis Ω, I, 1. This is a manuscript in one of the libraries in the royal seat of El Escorial in Spain.

The variant reading found in C, Ῥογδιοι [Rhogdioi] can probably be dismissed as a transmissional error due to eyeskip. The copyist who introduced this error skipped from the first omicron [ο] in Ῥοβογδιοι [Rhobogdioi] to the second, with the result that two letters were inadvertently omitted. This is a common scribal error.

The variant reading in O, Ῥοβονδιοι [Rhobondioi], can also be safely dismissed as a simple misreading of Ῥοβογδιοι [Rhobogdioi] due to the similarity of the minuscule letters gamma and nu. The Ptolemaic forms of these letters are not particularly alike, so this error probably crept in during the Byzantine era, when Greek minuscule was first introduced:

The two remaining variants—Ῥοβογδοοι [Rhobogdooi] and Ῥοβουγδιοι [Rhobougdioi]—are not so easily explained away. The former only occurs in a single manuscript, which greatly undermines any claims it might make to originality. The latter, however, can be found in half a dozen sources. Nevertheless, the critical form chosen by modern editors occurs in about forty manuscripts, including the oldest, so it is probably safe to accept this as the correct form.

A Note on Ptolemy’s Diacritics

In ancient Greek, an initial rho, Ρ [R], always took a rough breathing:

13. Every initial ρ has the rough breathing:_ ῥήτωρ orator_ (Lat. rhetor). Medial ρρ is written ῤῥ in some texts: Πυῤῥος Pyrrhus.

14. The sign for the rough breathing is derived from Η, which in the Old Attic alphabet (2 a) was used to denote h. Thus, ΗΟ ὁ the. After Η was used to denote η, one half (ⱶ) was used for h (about 300 B.C.), and, later, the other half (˧) for the smooth breathing. From ⱶ and ˧ come the forms ῾ and ᾽. (Smyth 10)

This explains why Ptolemy’s Ῥοβογδιοι is sometimes transcribed into Roman script as Robogdii (O’Rahilly) and sometimes as Rhobogdii (Müller, Wilberg). The former, as we shall see, is probably closer to the original Celtic name, so the introduction of the rough breathing here is simply the result of Ptolemy or one of his transcribers applying Smyth’s general rule.

Identity

In the late 17th century, the Irish historian Roderic O’Flaherty confessed himself at a loss to account for most of the tribal names in Ptolemy’s geography of Ireland:

We must indeed declare, that those tribes and septs which have been summed up by Ptolomy, are as foreign to us in sound as the Savage nations of America; such as the ... Rhobogdii ... (O’Flaherty & Hely 23)

Two centuries later, Goddard Orpen suggested the following etymology for this particular ethnonym:

In connexion with the position assigned to the Ῥοβόγδιοι, it is remarkable that the “Book of Invasions” gives the names Boc and Roboc as those of certain of the Fomori, who in the days of Nemid built Rath Chinnech in Ui Niallain, now the barony of Oneilland in the north of Co. Armagh, and Rath Cimbaoith in Seimhne in Dal Aradia (Co. Antrim). This Roboc may have been the ancestor, historical or legendary, of the Rhobogdii ... (Orpen 117)

Orpen believed that the Robogdioi were pre-Celtic, but as I have tried to demonstrate in these and other articles on the Short Chronology, there were no pre-Celtic people in post-glacial Ireland. The pre-Celts of mainstream academia are figments of the archaeologists’ imaginations, and the archaeological remains that have been attributed to them are misdated Celtic artifacts. If the Fomorians of Irish mythology are not entirely mythical, they are probably to be identified with the Priteni, the first Celts to settle these islands after the ice sheets withdrew. The Priteni, who arrived around 750 BCE, were primitive hunter-gatherers. They have been misdated by mainstream archaeology and classified as Mesolithic hunter-gatherers of 7000-5000 BCE.

Ptolemy located the Robogdioi in the northeast corner of Ireland. In historical times, this was the territory of the Dál Riata. It is no surprise, therefore, that some scholars have concluded that the Robogdioi and the Dál Riata were one and the same people. Even T F O’Rahilly was willing to accept a possible connection between the two—albeit at the cost of scribal accuracy:

Robogdii. Their position corresponds to that of the Dál Riata (Mod. Ir. Dál Riada) of historical times; these took their name from a mythical ancestor Riata (otherwise Eochu Riata, or Cairbre Rigfhota), whose name would go back to *Rēdodios (see p. 295). Ptolemy’s text is so liable to corruption that it is not inconceivable that his Ῥοβογδιοι [Rhobogdioi] is to be amended to Ῥειδοδιοι [Rheidodioi].

Thus we have Eochu Riata, eponym of the Dál Riata, whose epithet I interpret as meaning ‘travelling (on horseback, or in a chariot)’, Celt. *Rēdodios, IE root reidh-. So the cognate Gaulish tribal name Rēdones (preserved in the place-name ‘Rennes’), meaning ‘riders on horseback, travellers in chariots’, probably implies the existence of a sing. *Rēdū as a name for the Otherworld-deity. (O’Rahilly 6-7, 295)

In the previous article, however, I tentatively identified the Dál Riata with Ptolemy’s Darinoi, the tribe Ptolemy placed to the south of the Rhobogdioi. As we saw, the Dál Riata claimed descent from Dáire, whose name has been widely connected with that of the Darinoi. So, if the Dál Riata, who occupied the northeast corner of Ireland in historical times, were the descendants of the Darinoi, who and where were the Rhobogdioi?

Northeast or Northwest

Recently, the independent researcher Martin Counihan has suggested a novel solution to this quandary:

The name of the Robogdii is Celtic and it means something like “the breakers” or “batterers”. The initial ro- is a common intensifying prefix in both Old Irish and Gaulish. The root of the name is bog-, corresponding to the Old Irish verb bongid (“breaks”, or “reaps”) and to the Gaulish bogio- (“breaker”, “destroyer”). So, Robogdii means “the great destroyers”, or more positively, “the great reapers”. It is essentially the same name, but with the g not elided, as that of the Boii, once one of the most widespread of the Iron-Age Celtic peoples of central Europe and of the north-east of Italy, who gave their name ultimately to Bohemia, Bavaria and Bologna ...

Ptolemy listed a headland, Promontorium Robogdium, carrying the name of the Robogdii. Modern scholars have been almost unanimous in identifying it with Fair Head, near Ballycastle at the north-eastern extremity of County Antrim. It is reasonable to assume that the Robogdii lived in the area containing the promontory which is named after them, and so it has been believed that the territory of the Robogdii was in Antrim. Here, an alternative hypothesis will be presented.

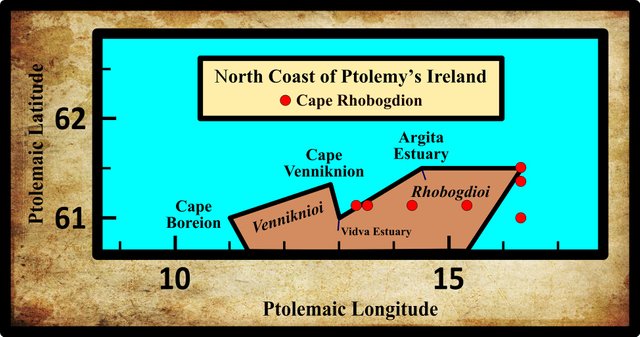

Besides Promontorium Robogdium, Ptolemy listed two other promontories around the northern coast, namely Promontorium Vennicnium, which has already been discussed, and Promontorium Boreum. He also lists the mouths of two rivers, Vidva and Argita, and an island, Ricina. The rivers are probably the Foyle and the Bann, although scholars have disagreed about which is which, or whether one of them might be some other river such as the Gweebarra. Ricina is Rathlin island, and is near the north-eastern corner of Ireland, about 5 km offshore from Fair Head. Ptolemy gives co-ordinates specifying the positions of these landmarks.

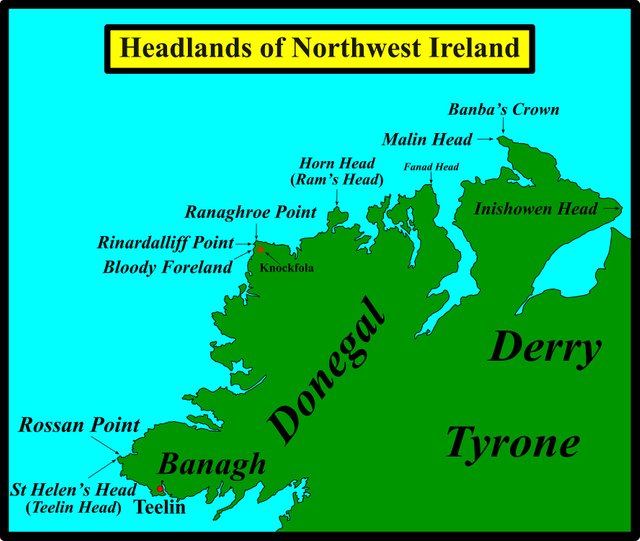

However, there are a couple of serious problems with Ptolemy’s account as it has come down to us. One problem is to do with the location of Promontorium Boreum: the name means “northern cape”, so one would expect it to be Ireland’s northernmost point, which is Malin Head on the Inishowen peninsula, north of Londonderry city, more or less in the centre of the north coast. But Ptolemy’s coordinates, straightforwardly interpreted, place the “northern cape” in a location much further to the west, and to the south of Malin Head: something is wrong.

The other problem concerns Promontorium Robogdium: its longitude seems much too great, placing it far to the east. Not only does its longitude imply that this promontory must be at the easternmost point of the coast, placing it presumably at Fair Head; but it leads to a map of Ireland which is grossly distorted, the north-east corner sticking out, with Fair Head being about 100 km too far to the east.

These problems can be explained by making two assumptions about how Ptolemy’s co-ordinates were copied from manuscript to manuscript over the ten centuries which passed before the first still-existing editions of the Geography were produced. Firstly, the coordinates of Promontorium Robogdium were switched with those of Promontorium Boreum. Secondly, the longitude of Promontorium Robogdium was erroneously copied, 12° being replaced by 16°. (In the original Greek, and also in Latin, this amounts to an error in a single digit, as it is in our modern numerals.) If that is what occurred, then Ptolemy’s original Promontorium Boreum would correspond, with reasonable precision, to Malin Head; while Promontorium Robogdium would be close to the western extremity of County Donegal and can be identified with Rossan Point.

That would mean that Fair Head was not included in Ptolemy’s original list of noteworthy promontories. But this need not surprise us, because Rathlin Island, which Ptolemy did include, is by itself a sufficiently distinctive landmark to guide any mariner in that area. As was mentioned above, Rathlin Island is very close to Fair Head, so it would in fact be slightly odd if Ptolemy had included both in the Geography.

By itself, the argument given above for placing Promontorium Robogdium at Rossan Point might be felt unconvincing by the experts who have placed it much further east. But it is bolstered by evidence from place-names. Without the prefix, the name of the Robogdii can be seen in that of the medieval clan known as the Cenél Boghaine. Their territory-name was eventually anglicised as Bowyne and as the barony-name Banagh. Banagh is in the south-west of County Donegal, being the area stretching westwards from Lough Eske to the sea, covering the northern coast of Donegal Bay. In early medieval times Banagh fell under the lordship of the O’Neill dynasty, and in 720 their ruler, Forbassach mac Sechnassach, was listed among the large number of nobles slain in the Battle of Allen, a well-deserved victory of the Leinstermen over the O’Neills. Today, the name of the Cenél Boghaine persists in two or three minor locations called Bogagh. It is suggested, therefore, that the land of Ptolemy’s Robogdii corresponds to the barony of Banagh. That being so, one would expect Promontorium Robogdium to be Rossan Point.

With the Robogdii located in the west of County Donegal, the order given earlier for the tribes clockwise around the coast of Ireland was incorrect: the Robogdii should precede the Vennicnii. Another consequence is that, since the inhabitants of Antrim were not the Robogdii, the Darini could have occupied rather more territory in that corner of Ireland than has previously been believed, and the Voluntii could have been further to the north. (Counihan 14-5)

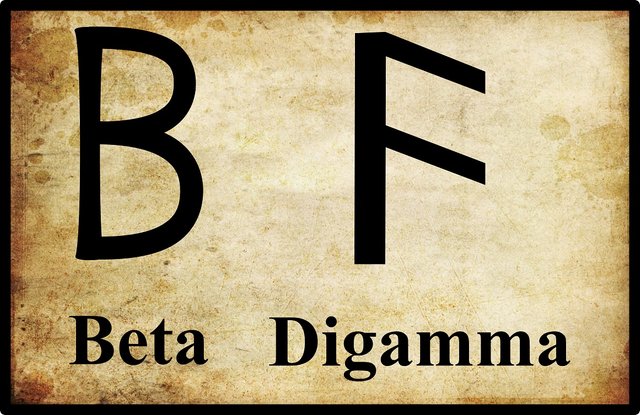

This is an ingenious, if highly speculative, solution to the problem. It is true that the Ptolemaic digits for 2 (beta) and 6 (digamma) bear a striking similarity, so it would not be surprising if they were confused by an early copyist. Also, several manuscripts place Cape Rhobogdion west of Ptolemy’s coordinates, though the most westerly of these, 13° 20', still leaves it east of the other two northern headlands.

On the other hand, the use of Rathlin Island [Rikina] to mark the northeast corner of Ireland does not sound terribly convincing to me. Also, Ptolemy’s latitude for Rikina is 17°, which is even more extreme than his latitude for Cape Robogdion (16° 20'). There is also the question of the identity of the middle promontory on the north coast, Cape Venniknion. If Cape Boreion (Northern Promontory) is Rossan Point and Cape Robogdion is Malin Head, then perhaps Cape Venniknion is Bloody Foreland (Cnoc Fola), the headland in the northwest corner of the island.

Another problem with Counihan’s hypothesis is that Cenél Boghaine are generally regarded as the descendants of Énna Bogaine, a historical character who is alleged to have lived in the 5th century CE. Of course, it is always possible that Énna took his surname from the region he colonized, so this criticism is not decisive. His father, Conall Gulban, took his surname from Benbulbin (Binn Ghulbain), a distinctive mountain in County Sligo (Joyce 140).

If you have read my earlier article on Cape Rhobogdion, you may recall that a number of early scholars believed that the name of the Robogdioi had been preserved in that of the episcopal seat of Robogh. This town was subsequently shown to be Raphoe, which is in County Donegal:

Rath-Both, now called Raphoe, seems to carry some Foot-steps of the Rhobogdii in it. (Ware & Harris 43)

Perhaps this could also be adduced in support of Counihan’s hypothesis, though Raphoe is generally derived from the Irish words ráth (ringfort) and both (hut, cell), and there is no evidence that it existed before the Christian era.

Roman Era Names

Counihan’s etymology for Robogdioi suggests that the people gave their name to the promontory. The etymologists at Roman Era Names, however, suggest that it was the other way round:

Ροβογδιον ακρον (Robogdion 2,2,2) was probably Fair Head, the north-north-eastern tip of Ireland opposite Rathlin Island (Ptolemy’s Ρικινα), though one cannot totally rule out other extremities, including Benbane Head (near the Giants Causeway) or Runabay Head. The name probably meant something like ‘great curve’, referring to the general shape of the coastline, where -bogd- (seen also in Medibogdo) probably came from *bheug- ‘to bend’, which led to OE boga ‘bow’. This rejects the Celticists’ theory that Ροβογδιοι people were ‘mighty fighters’, but retains their idea of initial Ro- as ‘great’, which might have evolved from PIE *per- ‘to pass over’, via *pro- then loss of initial P, or from PIE *ghreu- ‘to grind’, the source of words such as gross and great, which lost an initial GH sound. (Roman Era Names)

Personally, I think it is more likely that the headland was named for the local inhabitants, and not the other way round. But who knows?

Conclusions

If the Dál Riata are to be identified as the descendants of Ptolemy’s Darinoi, then we will have to accept either that Counihan is right and Ptolemy’s Robogdioi have been misplaced or that the Robogdioi became extinct as an independent nation sometime between the 4th century BCE, the era Ptolemy is describing, and the 5th century CE, when written history began.

A third possibility is that the Robogdioi simply migrated from the northeast of Ireland to the northwest at some point during this interval of 750 years. Such migrations, usually due to military conquest, were quite common in ancient Ireland.

References

- Martin Counihan, Researchgate (2019)

- Patrick S Dinneen, Foclóir Gaedhilge agus Béarla: An Irish-English Dictionary, Irish Texts Society, M H Gill & Son, Ltd, Dublin (1904)

- Patrick Weston Joyce, The Origin and History of Irish Names of Places, Volume 1, Longmans, Green, & Co, London (1910)

- Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, Eighth Edition, American Book Company, New York (1901)

- Karl Wilhelm Ludwig Müller (editor & translator), Klaudiou Ptolemaiou Geographike Hyphegesis (Claudii Ptolemæi Geographia), Volume 1, Alfredo Firmin Didot, Paris (1883)

- Karl Friedrich August Nobbe, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographia, Volume 1, Karl Tauchnitz, Leipzig (1845)

- Karl Friedrich August Nobbe, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographia, Volume 2, Karl Tauchnitz, Leipzig (1845)

- Roderic O’Flaherty, James Hely (translator), Ogygia, Or, A Chronological Account of Irish Events, Volume 1, W McKenzie, Dublin (1793)

- Thomas F O’Rahilly, Early Irish History and Mythology, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, Dublin (1946, 1984)

- Goddard H Orpen, Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland, The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Volume 4 (Fifth Series), Volume 24 (Consecutive Series), pp 115-128, Dublin (1894)

- Claudius Ptolemaeus, Geography, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vat Gr 191, fol 127-172 (Ireland: 138v–139r)

- Herbert Weir Smyth, A Greek Grammar for Colleges, American Book Company, New York (1920)

- Rudolf Thurneysen, Osborn Bergin (translator), D A Binchy (translator), A Grammar of Old Irish, Translated from Handbuch des Altirischen (1909), Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, Dublin (1946, 1998)

- James Ware, Walter Harris (editor), The Whole Works of Sir James Ware, Volume 2, Walter Harris, Dublin (1745)

- Friedrich Wilhelm Wilberg, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographiae, Libri Octo: Graece et Latine ad Codicum Manu Scriptorum Fidem Edidit Frid. Guil. Wilberg, Essendiae Sumptibus et Typis G.D. Baedeker, Essen (1838)

Image Credits

- Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland: Wikimedia Commons, Nicholaus Germanus (cartographer), Public Domain

- Greek Letters: Wikimedia Commons, Future Perfect at Sunrise (artist), Public Domain

- T F O’Rahilly: Copyright Unknown, Fair Use

- Benbulbin: Jon Sullivan (photographer), Public Domain

- Fair Head, County Antrim: © 2018 Outdoor Concepts, Fair Use

very good post dear. I am back . i missed your reading so much bro