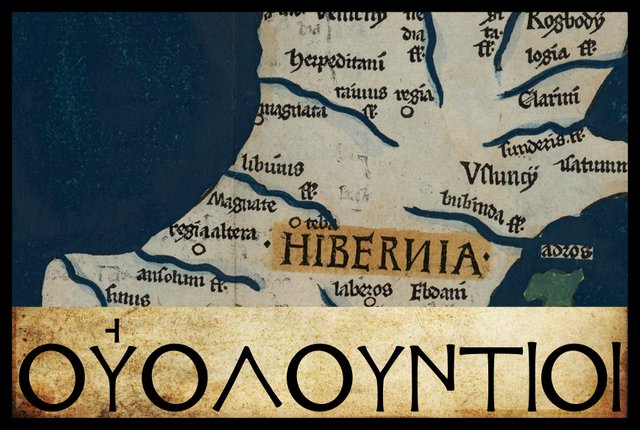

Οὐολουντιοι

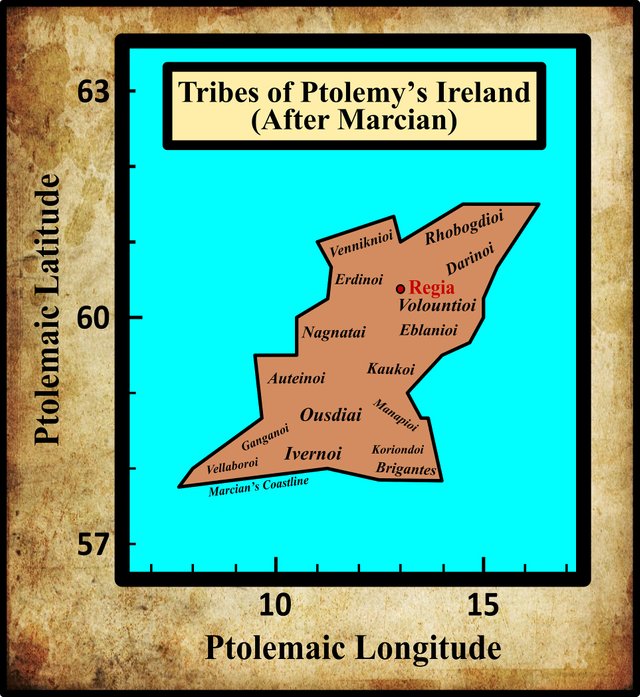

In his description of Ireland, Geography 2:2 §§ 1-10, Claudius Ptolemy records the disposition of sixteen Irish tribes. Beginning, as before, in the southeast corner of the island and proceeding in a counterclockwise direction, the sixth of these are the Volountioi (Latin: Voluntii). These are listed among the tribes who dwell on the east coast. Their territory lies south of that of the Darinoi and north of that of the Eblanoi.

Two variant readings of this ethnonym were noted by Karl Müller in his 1883 edition of Ptolemy’s Geography:

| Source | Greek | English |

|---|---|---|

| Most MSS | Οὐολουντιοι | Volountioi |

| X, L, Σ, Φ, Arg, Mannert, Ulm, 4803 | Οὐσλουντιοι | Ouslountioi |

| Ψ | Οὐσλοντιοι | Ouslontioi |

X is Vaticanus Graecus 191, which dates from about 1296. It is believed that this manuscript preserves a very ancient tradition. Ptolemy’s description of Ireland is on folia 138v–139r. Curiously, Müller does not include this MS among those which have the variant Οὐσλουντιοι [Ouslountioi], but it clearly should be included.

L is a manuscript from the library at Vatopedi, the ancient monastery on Mount Athos in Greece.

Σ, Φ and Ψ are three manuscripts from the Laurentian Library in Florence: Florentinus Laurentianus 28, 9 : Florentinus Laurentianus 28, 38 : Florentinus Laurentianus 28, 42.

Arg is the Editio Argentinensis, which was based on Jacopo d’Angelo’s Latin translation of Ptolemy (1406) and the work of Pico della Mirandola. Many other hands also worked on it—Martin Waldseemüller, Matthias Ringmann, Jacob Eszler and Georg Übel—before it was finally published by Johann Schott in Straßburg in 1513. Argentinensis refers to Straßburg’s ancient Celtic name of Argentorate.

Mannert refers to a pair of Latin manuscripts discovered by the Prussian geographer Konrad Mannert.

Ulm is an edition of Ptolemy’s Geography published in Ulm in 1482 by Lienhart Holle, with the assistance of the cartographer Nicolaus Germanus Donis.

4803 is one of the Codices Parisini Latini in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris. It is a Latin translation of Ptolemy’s Geography by Jacopo d’Angelo: Latin 4803.

Müller suggests that the correct form of this ethnonym was Οὐλσουντιοι [Oulsountioi] because he believes that this name represents the original form of the modern name Ulster. But this is nonsense. The -ster in Ulster, like that in Leinster and Munster, is a late accretion, introduced by the Norsemen in the Middle Ages. It is believed to derive from the Old Norse word staðr, meaning place. In our native records, the earliest surviving form of the Celtic name of Ulster and its ruling tribe is Ulaid.

In Celtic, v was pronounced like our modern semivowel [w], as it was in Classical Latin. In later forms of Irish, [v] and [w] are found, depending on the context and the dialect. As we have seen several times before in this series, Ptolemy used the Greek digraph ου [ou] to represent the Celtic letter v because the Greek letter digamma, which had formerly represented this sound, had fallen out of use (except as the numeral 6). T F O’Rahilly explained this practice in his Early Irish History and Mythology in connection with the Greek names for Ireland:

The name ’Ιέρνη, “Ireland”, had probably been picked up by the Massaliot Greeks, from merchants and from their Celtic neighbours, as early as the fifth century B.C. ... The digamma had disappeared from Ionic as early as the seventh century B.C.; and when Massaliot Greeks first heard the name Īvernā [Ireland], they presumably had no means of indicating the -v- and simply dropped it. Later the Greeks adopted the expedient of representing v in foreign names by ου ... We may take it that Pytheas [believed by O’Rahilly to be Ptolemy’s principal source for Ireland] retained the traditional name ’Ιέρνη ... whereas in dealing with other names previously unrecorded, we find him representing Celtic v by Greek ου, as for instance in ... Bouvinda [Βουουινδα] ... Ptolemy, or some near predecessor of his, modernized ’Ιέρνη into ’Ιουερνία [Ivernia] ... (O’Rahilly 41-42)

The question we must ask ourselves is, then: Is this the case with Οὐολουντιοι? Does this represent Volountioi? If the initial Οὐ- represents the semivowel spelt as V and pronounced as [w], then the following letter must have been a vowel. This would imply that the two variant readings with Οὐσ- [Ous-] must be incorrect, as they would have to be read as Ws-, which is nonsensical in the context of a Celtic name. On the other hand, if the correct reading had -σ- [-s-], then the initial Οὐ- [Ou-] would have to be read as a vowel or diphthong.

Ptolemy did use the digraph ου to represent both a semivowel and a vowel (or diphthong). His spelling for Bouvinda, the River Boyne, is Βουουινδα, where this digraph appears twice in succession, the first time as a vowel or diphthong and the second time as a semiwovel. He even employed this digraph twice in the very ethnonym we are now discussing, once as a semivowel (supposedly) and once as a vowel or diphthong. See the Wikipedia article Ancient Greek Phonology for further information on this subject.

A Note on Ptolemy’s Diacritics

For the fifth time in this series, I quote Amalia Gnanadesikan, the Technical Director for Language Analysis at the University of Maryland’s Center for Advanced Study of Language, on the use of diacritics in ancient Greek. In her book The Writing Revolution, she makes the following pertinent comment on the question of smooth and rough breathing in Ptolemy’s Alexandria:

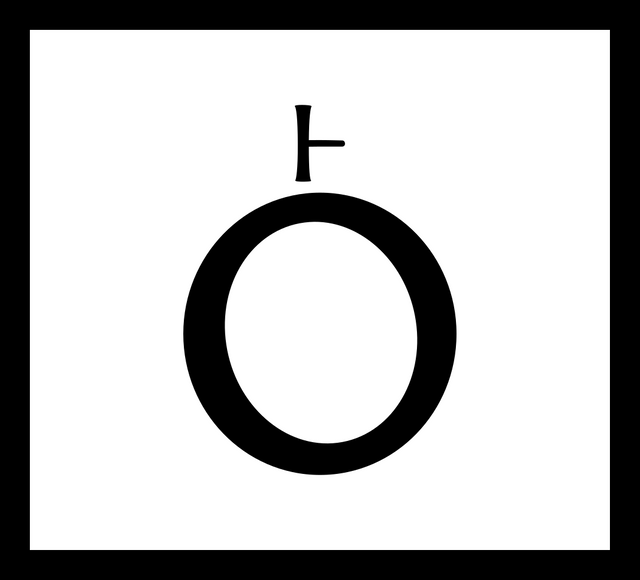

In the process of accumulating and copying texts, the Alexandrian scholars began to show concern for matters of orthography. They found that at certain points the lack of a written form of [h] made for ambiguity. They noted that the Greeks living in Italy had been more free-thinking than the Athenians. While they had gone along with the adoption of the Ionic alphabet, they continued to write [h] by cutting the hēta in half and using ├. The Alexandrians adopted the Italian Greeks’ half H, but wrote it as a superscript on the following vowel, so that, for example,

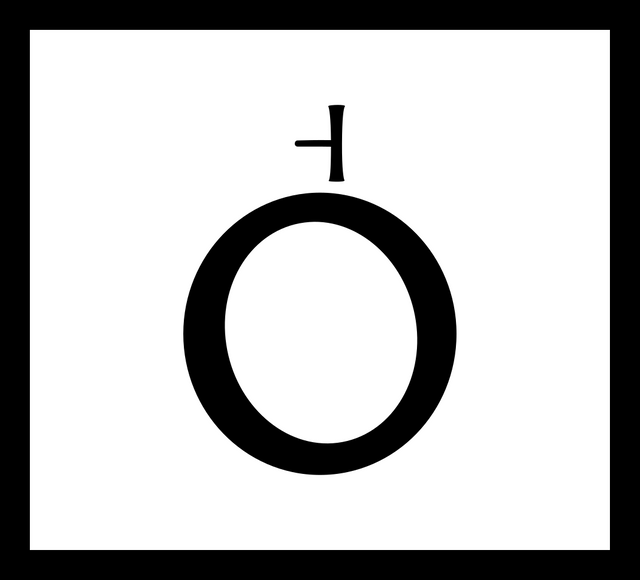

was ho. Loving symmetry, they made the other half of H stand for the lack of an [h] sound before a vowel:

These diacritics came to be termed “rough breathing” (for [h]) and “smooth breathing” (for lack of [h]). Their use was for many centuries largely reserved for cases where ambiguity could arise without them. These marks later became ‘ and ’, so that ὁ was ho and ὀ plain o ... Only by the ninth century AD (well into the Byzantine period, AD 330–1453) did the use of breathing and accent diacritics become fully regular, with all vowel-initial words marked for “rough” or “smooth” breathing and all words marked for accent. (Gnanadesikan 220 ... 221)

I take these remarks to imply that Ptolemy probably only employed the diacritics for smooth and rough breathings in cases where the correct reading was not already obvious to the reader. In other words, he probably did not include the breathing in common Greek words, as its presence in such words was too well known to require inclusion. In the case of foreign toponyms and ethnonyms, however, he probably did include it. Hence we have Ἰουερνις rather than Ιουερνις.

Unfortunately, Gnanadesikan does not consider the exceptional case where an initial ου- [ou-] represents the Celtic semiwovel spelt V and pronounced [w]. Did Ptolemy include the smooth breathing in this case? I have decided to include the smooth breathing, since it is included in the surviving Byzantine manuscripts.

The pitch accents—acute, grave and circumflex—were probably not employed by Ptolemy at all. This is the practice I have followed in this series.

It need hardly be repeated that Ptolemy lived in an age before the development of what we today might call the lowercase Greek letters:

Another invention of Byzantine times was the small letters, or minuscules. Ancient Greek was written entirely in what we now consider capital letters. All in all, ancient Greek inscriptions are rather difficult for modern readers, used as we are to visual cues such word spacing, punctuation, and capitalization. (Gnanadesikan 221)

There is not a close similarity between the Ptolemaic forms of the letters sigma and omicron, but in the Byzantine era the minuscule forms of these letters could easily be confused. This applies especially to the minuscule form of sigma that is found in VatGr 191, a form virtually identical to the modern lowercase sigma. It is likely, therefore, that the corruption of Ptolemy’s Οὐο- to Οὐσ- (or vice versa) occurred during the Byzantine era.

Identity

There can be little doubt that Ptolemy’s Volountioi refers to the Ulaid, the Celtic tribe that dominated the northern part of Ireland in ancient times and for whom the province of Ulster was named. The Ulaid were clearly a tribe of Belgic Celts, or Belgae, variously known in Irish tradition as the Fir Bolg, the Builg and the Érainn:

Among the branches of the Érainn in early historical times were ... Dál Fiatach, the historical representatives of the ancient Ulaid ... [Footnote: Even if we had no other evidence, some of the names occurring in the Ulidian tales would suggest plainly that the ancient Ulaid were Érainn or Builg ...] (O’Rahilly 81)

T F O’Rahilly was in no doubt that Ptolemy’s Volountioi referred to these people:

Voluntii_, a corruption of *Uluti, = Mid. Ir. Ulaid. The traditional capital of the Ulaid was Emain, near Armagh. In historical times we find them deprived of most of their territory, and retaining their independence only in eastern Down, where they were known as Dál Fiatach. (O’Rahilly 7)

Roman itineraries of Britain are alleged to have placed a native tribe called the Voluntii in Lancashire. Unfortunately, the only source I can find for this is the Itinerary of Richard of Cirencester, The Description of Britain, a work that is now generally acknowledged to be a late forgery. If, however, there really was a British tribe of this name, then it is possible that the original form of Ptolemy’s Irish tribal name was Οὐλουτοι [Uluti], or something similar, and that this was corrupted to Οὐολουντιοι [Voluntii] under the influence of this better known British ethnonym.

Ptolemy’s Volountioi have been understood to refer to the Ulaid for several centuries. As early as the 17th century, the Irish antiquary James Ware suggested that Ulster was indebted to these people for its name (Ware & Harris 44), a view that was endorsed at the end of the following century by another Irish antiquary William Beauford (Beauford 67). In the early 18th century, the Welsh scholar William Baxter etymologized the name Ulster as Voluntiorum Terra, Latin for Land of the Voluntii (Baxter 254). In the 19th century Karl Müller, as we have seen above, emended Ptolemy’s text in the belief that the Volountioi had given their name to Ulster (Müller 79). A few years later, Goddard Orpen equated the Volountioi with the Ulaid and identified the “city” of Rēgia with Emain Macha, the ancient capital of the Ulaid (Orpen 126).

The etymologists at Roman Era Names also connect Volountioi and Ulaid, while also suggesting an alternative provenance of the name:

Ουολουντιοι (Woluntioi 2,2,9) lived further south, around the border of modern Northern Ireland. The name is possibly Celtic for ‘bearded’, like OI ulach and a precursor of the later Ulaid people. A better parallel may be Latin voluntas ‘freewill, desire’, from PIE *wel- ‘to will, to wish’, implying that these people were happy to see traders. (Roman Era Names)

Conclusions

In my opinion, there is little doubt that Ptolemy’s Volountioi refers to the historical Ulaid, the ancient Belgic tribe who dominated the northern part of Ireland in ancient times to such an extent that they gave their name to this part of the island—a name that stubbornly clung to it long after the Ulaid had lost their independence to the Goidelic Celts and faded from history.

I concur with Goddard Orpen’s opinion that the settlement of Rēgia represents their stronghold at Emain Macha, or Navan Fort, in County Armagh. Ptolemy’s coordinates for this “city” place it inland in the same part of the country as the Volountioi.

References

- William Baxter, Glossarium Antiquitatum Britannicarum, sive Syllabus Etymologicus Antiquitatum Veteris Britanniae atque Iberniae temporibus Romanorum, Second Edition, London (1733)

- William Beauford, Letter from Mr. William Beauford, A.B. to the Rev. George Graydon, LL.B. Secretary to the Committee of Antiquities, Royal Irish Academy, The Transactions of the Royal Irish Academy, Volume 3, pp 51-73, Royal Irish Academy, Dublin (1789)

- Amalia E Gnanadesikan, The Writing Revolution: Cuneiform to the Internet, Blackwell Publishing, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, Chichester (2009)

- Karl Wilhelm Ludwig Müller (editor & translator), Klaudiou Ptolemaiou Geographike Hyphegesis (Claudii Ptolemæi Geographia), Volume 1, Alfredo Firmin Didot, Paris (1883)

- Karl Friedrich August Nobbe, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographia, Volume 1, Karl Tauchnitz, Leipzig (1845)

- Karl Friedrich August Nobbe, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographia, Volume 2, Karl Tauchnitz, Leipzig (1845)

- Thomas F O’Rahilly, Early Irish History and Mythology, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, Dublin (1946, 1984)

- Goddard H Orpen, Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland, The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Volume 4 (Fifth Series), Volume 24 (Consecutive Series), pp 115-128, Dublin (1894)

- Claudius Ptolemaeus, Geography, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vat Gr 191, fol 127-172 (Ireland: 138v–139r)

- James Ware, Walter Harris (editor), The Whole Works of Sir James Ware, Volume 2, Walter Harris, Dublin (1745)

- Friedrich Wilhelm Wilberg, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographiae, Libri Octo: Graece et Latine ad Codicum Manu Scriptorum Fidem Edidit Frid. Guil. Wilberg, Essendiae Sumptibus et Typis G.D. Baedeker, Essen (1838)

Image Credits

- Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland: Wikimedia Commons, Nicholaus Germanus (cartographer), Public Domain

- Greek Letters: Wikimedia Commons, Future Perfect at Sunrise (artist), Public Domain

- T F O’Rahilly: Copyright Unknown, Fair Use

- Navan Fort (Emain Macha): © Ellen Bell, Fair Use